Chapter 39 Diagnosis and Management of Asthma in Adults

Definition and Key Features of Asthma

Asthma is derived from the Greek word aazein, meaning “to labor in breathing” and was first used by Hippocrates, in 450 BCE, to describe a condition characterized by spasms of breathlessness. The present Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) definition of the disease (Box 39-1) is a lengthy description of histopathologic, pathophysiologic, and clinical features that encompass the major disease characteristics. Fundamental features are airway hyperresponsiveness, chronic airway inflammation, disordered airway mucosal immunity, and structural changes to the airways (airway remodeling).

Box 39-1

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Description of Asthma

From Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (Update 2009). Available at www.ginaaasthma.org.

Airway Hyperresponsiveness

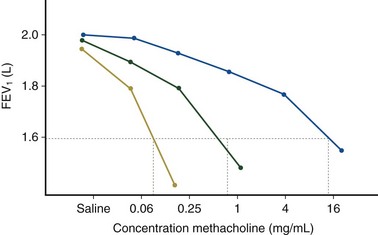

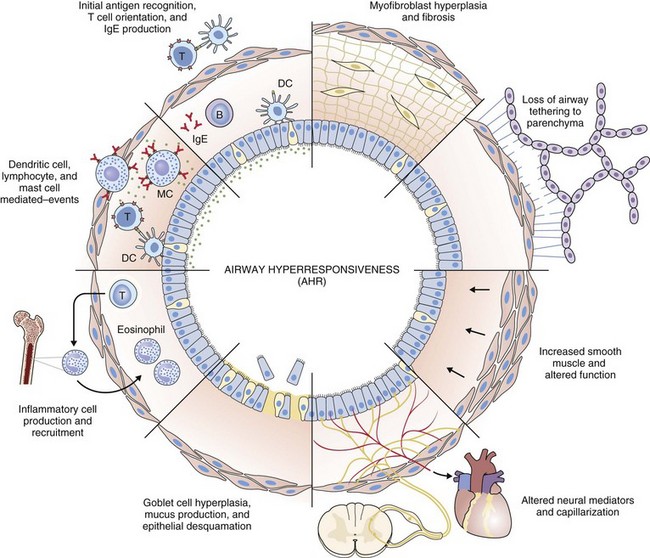

Airway hyperresponsiveness can be objectively demonstrated as a 20% fall in the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) after inhalation of histamine or methacholine) at a concentration below 8 mg/mL. This represents an abnormal effector response of airway smooth muscle, characterized by heightened pharmacologic sensitivity and reactivity to the bronchoconstrictor stimulus (Figure 39-1). Naturally occurring airway hyperresponsiveness reflects an abnormally amplified response of airway nerves and mast cells to exogenous stimuli, as well as an intrinsic abnormality of the airway smooth muscle response. The basis for this generalized hyperresponsiveness is not entirely clear, but sensitization of airway nerves, mast cells, and smooth muscle by inflammatory mediators, along with loss of epithelial barrier function, reduced production of bronchoprotective factors, an intrinsic abnormality of airway smooth muscle, and structural changes to the airway, all are likely to play a part (Figure 39-2). One key pathologic feature associated with airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma not seen in nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis is infiltration of the bronchial smooth muscle layer by mast cells, implying that the interaction between these cells is fundamentally important in the pathogenesis of airway hyperresponsiveness.

Chronic Airway Inflammation

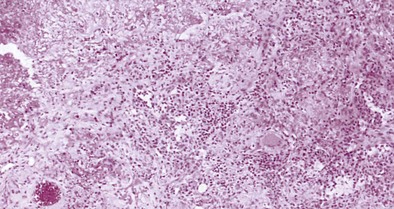

Histopathologic examination of postmortem specimens from patients with fatal asthma show an inflammatory response characterized in many cases by the presence of airway eosinophilia. Typically, eosinophilic infiltration can be found throughout the airway wall, within thick viscid plugs that occlude the airway lumen and often extend into the lung parenchyma and alveolar spaces and even into adjacent blood vessels (see Figure 39-2). In addition, extensive eosinophilic degranulation with deposition of major basic proteins occurs. Associated findings include widespread shedding of the airway surface epithelium, thickening of the reticular basement membrane, and enlargement of airway smooth muscle and submucosal glands. A minority of patients dying from asthma, particularly those with sudden-onset fatal asthma, exhibit evidence of eosinophilic inflammation. In these cases it is believed that widespread mast cell degranulation is the primary event with evidence for a relative excess of neutrophils in the distal airways and parenchyma.

Structural Changes to the Airway

Structural changes in airway morphology (airway remodeling) probably occur as a result of chronic airway inflammation and dysfunction. These changes are likely to be the basis for the accelerated lung function decline and fixed airflow obstruction seen in some patients with asthma. Key features of airway remodeling include thickening of the subepithelial basement membrane caused by abnormal deposition of collagen, increased airway smooth muscle bulk, increased mucus-secreting cells, and increased airway vascularity (see Figure 39-2). In severe asthma, bronchiectasis, small airway fibrosis, and emphysema may be features. The bronchiectasis is associated with sensitization to Aspergillus.

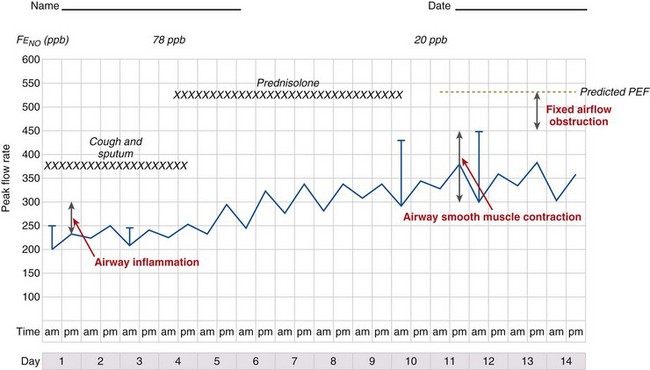

Pathophysiologic Basis of Asthma

It is likely that these factors contribute to airflow obstruction and morbidity in different ways (Figure 39-3). Airway hyperresponsiveness is responsible for short-term, bronchodilator-responsive variable airflow obstruction which is the basis for many of the day-to-day symptoms experienced by patients and is suppressed by bronchodilator therapy, and to a lesser extent corticosteroids. Bronchitis, which may be eosinophilic and corticosteroid-responsive or neutrophilic and corticosteroid-unresponsive, manifests with cough and sputum and a relatively bronchodilator-resistant but potentially corticosteroid-responsive airflow obstruction of more gradual onset. Inflammation-mediated airflow obstruction is particularly important in the pathogenesis of asthma attacks. Cough and a small amount of sputum production is common in asthma. It probably reflects airway inflammation but also may be due to cough reflex hypersensitivity, a common but poorly understood and difficult-to-treat aspect of asthma and other airway diseases. Airway damage may manifest with disability caused by bronchodilator and corticosteroid-resistant airflow obstruction or mucus retention and infection as a result of airway and lung parenchymal damage. Extrapulmonary conditions linked to the inflammatory airway disease or independent of it also may contribute to symptoms (Box 39-2).

Diagnosis

One of the problems facing clinicians and epidemiologists is the absence of a “gold standard” modality for defining or diagnosing asthma. Characteristic clinical features (Box 39-3) coupled with objective demonstration of variable airflow obstruction and/or airway hyperresponsiveness usually will provide sufficient evidence to make the diagnosis.

Box 39-3

Factors Affecting Likelihood of Asthma as Cause of Respiratory Symptoms*

Factors Associated With Increased Probability of Asthma

More than one of the following symptoms: cough, breathlessness, wheeze, chest tightness

Symptoms worse at night and in the early morning

Symptoms occurring in response to exercise, allergen exposure, and cold air

Symptoms developing after taking aspirin or beta blockers

Family history of asthma and/or atopic disorder

Variable wheeze heard on auscultation of the chest

History

Asthma symptoms typically are variable reflecting variability in airflow obstruction and other aspects of the disease. Exaggerated diurnal variation in physiologic bronchomotor tone causes airflow obstruction and symptoms at night, maximally at 4 AM. Other symptoms reflect airway hyperresponsiveness to a multitude of possible trigger factors. Symptoms occurring after exercise, after exposure to allergens, and in response to inhaled noxious fumes such as cigarette smoke are most commonly reported. Box 39-3 lists some of the symptoms that increase and decrease the probability of asthma. An assessment of disease severity can be made from the frequency of daily symptoms, exercise limitation, nocturnal wakening, and exacerbation frequency (Table 39-1).

Clinical Examination

Measuring Variability in Airflow Obstruction

Diurnal variation in peak expiratory flow (PEF): Calculated from serial PEF measurements (see Figure 39-3); typically expressed as the difference between the highest and lowest daily readings as a percentage of the mean (see Table 39-1)

Assessment of the bronchodilator response: Measured as the change (improvement) in FEV1 or PEF from baseline with either a short-acting bronchodilator (bronchodilator responsiveness) or after a therapeutic trial of corticosteroid (steroid responsiveness)

Assessment of airway responsiveness: Measuring the fall in FEV1 in response to bronchoconstrictor stimuli, including pharmacologic agents (methacholine or histamine challenge tests), exercise, and allergen challenge (see Figure 39-1)

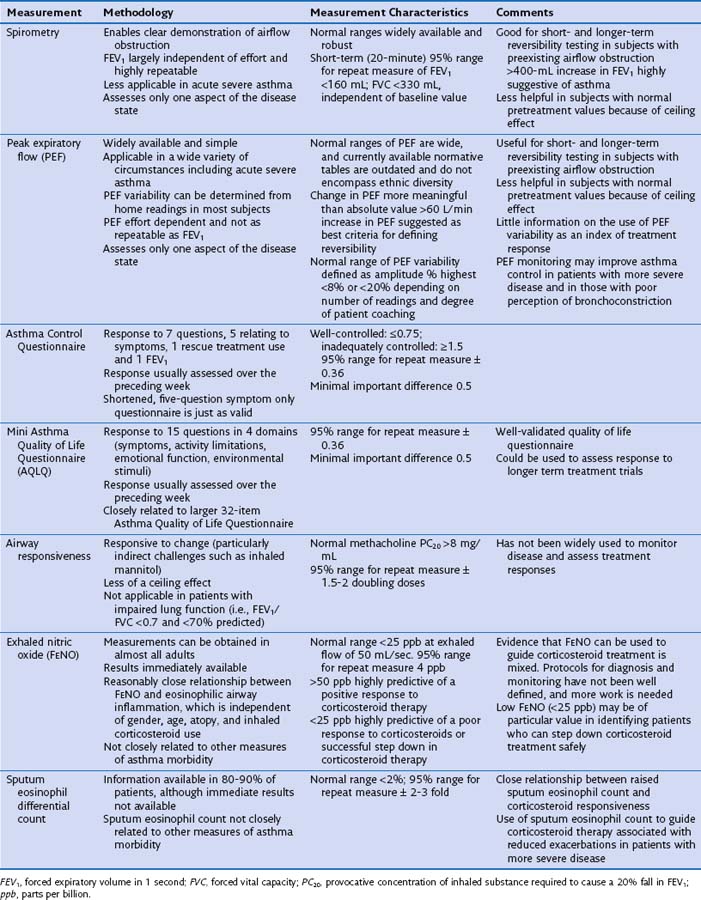

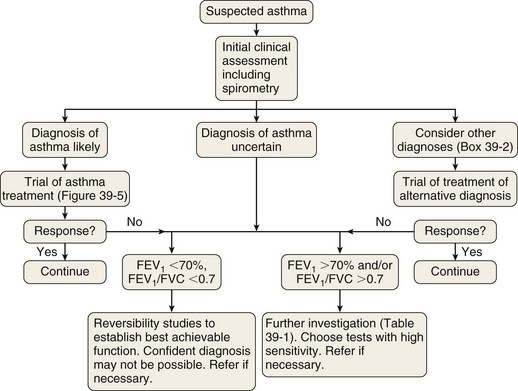

The measurement characteristics of the various tests to assess variable airflow obstruction and asthma in general are outlined in Table 39-1. An algorithm for the assessment of patients with suspected asthma is presented in Figure 39-4.

Diagnostic Pathway

The diagnostic pathway followed will depend on the pretest probability for the diagnosis, response to therapy, and level of clinical suspicion for an alternative diagnosis. The scope of the differential diagnosis is quite different in patients with and without airflow obstruction (see Box 39-2), and the main diagnostic question also is different. In the former, the clinician often is seeking support for a clinical diagnosis of asthma and the initiation of antiasthma therapy; in the latter, the evidence for an airway problem is more clear-cut, and the question is not whether inhalers should be used but how intensive the corticosteroid component of that therapy should be.

Management of Stable Asthma

Aims

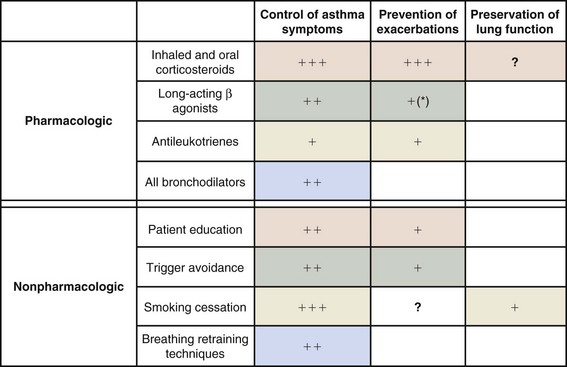

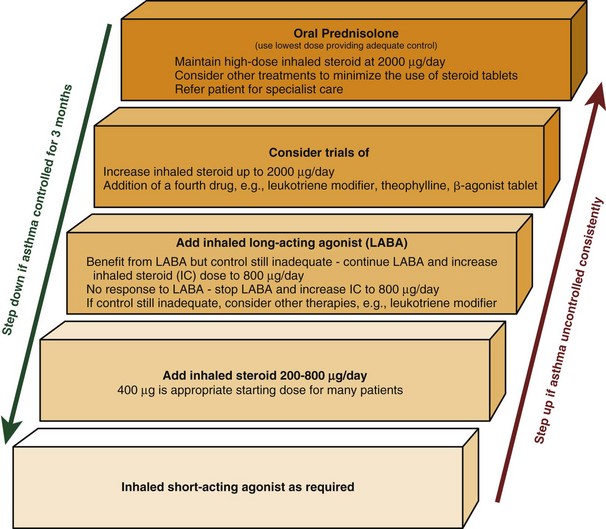

Both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic measures play an important role in achieving these aims (Box 39-4; Figures 39-5 and 39-6).

Box 39-4

Goals of Asthma Management

Figure 39-5 Stepwise approach to asthma management in adults.

(Modified from British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.)

Control of Symptoms

Asthma symptoms are a cause of both physical and psychological morbidity that exert considerable impact on quality of life. Any of several well-validated questionnaires can be used to assess the control of asthma symptoms (see Table 39-1).

Pharmacotherapy in Asthma

Stepwise Algorithm for Asthma Treatment

Guidelines recommend the titration of therapy for asthma in a stepwise manner, with the primary aim of satisfactorily controlling symptoms at the lowest dose of corticosteroid (see Figure 39-5). Changes in therapy should be reviewed every 3 months until stability is achieved. This algorithm assumes clinical control is concomitantly associated with control of underlying airway inflammation and therefore fulfillment of all three targets of care.

Monitoring Asthma Control and Guided Self-Management Plans

A number of potential tools are available to assess asthma (see Table 39-1). All such tools assess different aspects of the disease, and it is likely that they provide complementary information. Objective symptom scores are particularly useful, because patients may adjust to their impairment and not question symptoms that are potentially reversible. The extent to which these assessments allow risk stratification is unclear; this is an important area for further study. Table 39-1 outlines the characteristics of some of the most common methods used to assess asthma.

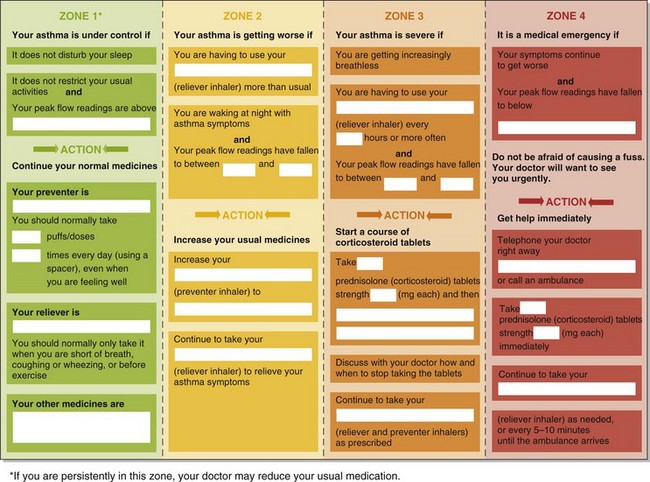

Regular review appointments also provide an opportunity to review patient education, inhaler technique, and self management skills. Self-management plans are individualized written protocols instructing patients in recommended courses of action on the basis of their asthma control that is graded and risk-stratified according to symptoms or peak flow (Figure 39-7). They are attractive for being patient-centered. Both symptom- and peak flow–guided plans lessen asthma morbidity and reduce the frequency of hospitalizations and unscheduled doctor visits. Although little evidence has been found for the superiority of one strategy over another, a peak flow–based plan may be more appropriate in patients with impaired perception of airflow obstruction.

Referral to a Specialist

• Patients with suspected occupational asthma

• Patients with treatment-refractory asthma, defined as those failing to achieve control despite appropriate high-dose therapy (BTS step 4 or 5). Although constituting 5% to 10% of the asthma population, this group accounts for over 60% of health care resource utilization for asthma in the United Kingdom. The reasons for a poor therapeutic response are multifactorial (Box 39-5).

• Patients at higher risk for asthma-related death (Box 39-6). Relative risk is additive; accordingly, patients with several minor risk factors, as well as those with a single major risk factor, require referral.

Box 39-5

Factors Contributing to Refractory or Severe Asthma

| Patient Factors | Disease Factors |

|---|---|

Coexistent aggravating disorders

High doses of oral or parenteral steroid usually overcome the impaired response to conventional therapy

High doses of oral or parenteral steroid usually overcome the impaired response to conventional therapyAbsence of demonstrable eosinophilic airway inflammation (noneosinophilic asthma)

GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Nonpharmacologic Aspects of Asthma Care

Patient Education

• Identifying and avoiding asthma triggers, the most important of which is smoking.

• Understanding the role of different prescribed therapies—that is, distinguishing between therapy for immediate relief from symptoms (“relievers”) and therapy to prevent or reduce the frequency of symptoms (“preventers”), to support compliance with therapy, which is a considerable problem in asthma care

• Encouraging compliance with medication

• Ensuring correct inhaler technique

Recent Developments in Asthma Management

• Inflammation-guided management (inflammometry)

• The use of a single inhaled combination treatment for relief and maintenance therapy

• The development of monoclonal antibody therapies as targeted antiinflammatory agents

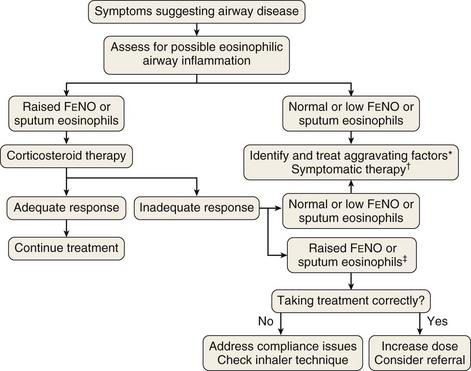

Inflammometry

The link between eosinophilic airway inflammation and corticosteroid responsiveness, together with the development of inexpensive nitric oxide monitors, has opened the way for a new approach to the management of airway disease in clinical practice, with the emphasis more on assessing airway inflammation than on diagnostic labeling. Figure 39-8 outlines an approach to assessment of patients presenting with new-onset airway disease whereby decisions about the use of corticosteroids are based on assessment of eosinophilic airway inflammation or FENO, rather than on recognition of patterns of symptoms and airway dysfunction.

Management of Important Patient Subgroups

Severe Asthma

A proportion of patients will have persistent symptoms despite appropriate treatment for moderate persistent asthma as just outlined. Although representing a relatively small minority, these patients experience much morbidity, consume significant health care resources, and probably are best managed in specialist settings. Severe asthma can be defined simply as asthma that continues to cause significant morbidity despite high-level antiasthma therapy (i.e., step 4 of the BTS asthma management guidelines) (see Figure 39-5).

Before additional therapeutic measures are considered, it is important to accurately confirm the diagnosis, to ensure that persistent symptoms are due to asthma, rather than to other aggravating or coexisting factors such as dysfunctional breathing, vocal cord dysfunction, obesity, bronchiectasis, COPD, rhinitis, or gastroesophageal reflux (see Box 39-5). Box 39-3 lists some features that increase the probability that non–asthma-related factors are responsible for persistent morbidity. Next, it is important to assess compliance with existing therapy, ideally using relatively objective measures such as prescription refill rates and blood theophylline and/or prednisolone levels. Poor adherence is very common in patients with severe asthma and has been linked with poor outcomes, notably an increased risk of fatal and near-fatal attacks. The best means to detect poor treatment adherence and to tackle it have yet to be established. This is an important area for further study.

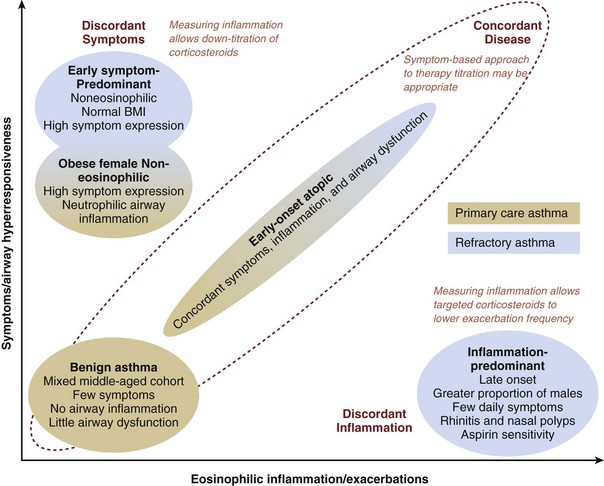

Recently there have been attempts to identify clinically important groups of patients using mathematical techniques such as factor analysis and cluster analysis. Figure 39-9 shows the results of one of the first attempts to phenotype patients with asthma recruited from primary care practices and from a severe asthma cohort being seen in a specialist hospital clinic. The main finding was that patients with severe asthma had more marked discordance in expression of symptoms and airway inflammation. The presence of these discordant phenotypes in patients with refractory asthma in particular suggests that a management approach which relies on symptoms to guide antiinflammatory treatment would result in suboptimal outcomes in a significant number of patients and that management guided by an objective measure of corticosteroid-responsive inflammation (i.e., eosinophilic airway inflammation) may be better. This is exactly what has been found in trials that have compared inflammation-guided use of steroids with symptom-guided use. The main outcome of these trials has been a reduction in the frequency of asthma attacks, suggesting that the main clinical benefit of controlling eosinophilic airway inflammation is to reduce the risk of attacks.

Churg-Strauss Syndrome

• Peripheral blood eosinophilia (presence of more than 1.5 × 109 cells/L)

• Systemic vasculitis involving two or more extrapulmonary organs

Biopsy of easily accessible affected tissue can be helpful to confirm the presence of vasculitis and extravascular granuloma (Figure 39-10) but should not delay institution of treatment. Antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are present in two thirds of cases, but this finding is not specific. The key to prompt diagnosis is maintaining clinical awareness of the condition, especially in an adult patient who presents with allergic rhinitis, sinusitis, asthma, or an eosinophilia (which can be marked), together with systemic features such as fever, rash (especially lower limb purpura), weight loss, or arthralgia. Other features include pulmonary infiltrates, peripheral neuropathy, cranial and other isolated nerve palsies, cerebrovascular accidents, abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, and, occasionally, intestinal perforation. Renal disease is uncommon, but cardiac involvement can occur and is a serious complication potentially leading to heart failure and sudden death. These manifestations of disease may develop over a short period, emphasizing the importance of a prompt diagnosis. The differential diagnosis clearly depends on the specific manifestation of Churg-Strauss syndrome occurring in the individual patient, but pulmonary manifestations may need differentiating from allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, other pulmonary eosinophilias, pulmonary sarcoidosis, Wegener granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, and polyarteritis nodosa.

Aspergillus-Associated Asthma

The fungus Aspergillus is globally distributed and found in soil and decaying leaf mold and vegetable matter. Fungal spores are dispersed by the wind, and peak levels are found during the autumn and winter. Some patients with asthma develop an IgE- and IgG-mediated response to Aspergillus and other molds on repeated exposure. Patients who are highly atopic, have long-standing disease, and exhibit evidence of airway damage are at particular risk. Some develop the arbitrarily defined condition allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), which features, in addition to asthma and Aspergillus sensitivity, pulmonary eosinophilia and infiltration with an intense allergic reaction in the proximal airways. This reactivity can result in bronchial occlusion, which may give rise to segmental or lobar collapse and, especially if untreated, significant bronchial wall damage and development of bronchiectasis of the proximal airways (Figure 39-11). It is becoming clear that less well-developed forms of this condition are common, and the term Aspergillus-associated asthma is preferred. Up to 40% of patients with severe asthma have Aspergillus sensitization, and many grow Aspergillus in their sputum when this organism is looked for specifically.

• A marked peripheral blood and sputum eosinophilia

• Demonstration of a positive result on immediate skin prick testing or RAST for A. fumigatus

• Positive precipitins (i.e., IgG antibodies) to A. fumigatus

• A. fumigatus grown on sputum culture

• A raised total immunoglobulin E level

• Lung imaging showing lobar collapse, infiltrates, and bronchiectasis, which is classically worst in the proximal airways in this condition (see Figure 39-11)

Occupational Asthma

Approximately 15% of patients with adult-onset asthma are thought to have occupational asthma. The causes, diagnosis, investigation, and management of occupational asthma are discussed in more detail in Chapter 40. The key point in the history is that symptoms are worse at work and better away from work, particularly with prolonged work absence during holidays. It should be possible to document this work effect objectively with PEF measurements done at work and away from work. A computerized analysis system is available online (see under “Web Resources”); this has been shown to be a valid means of diagnosing occupational asthma provided accurate and frequent (i.e., every 2 hours during waking hours) PEF readings are available. Occupational asthma results in considerable expense to the patient as a result of lost productivity, estimated to be in the order of £13 million in the United Kingdom over the course of his or her lifetime. Society contributes a similar amount, so reducing the incidence of occupational asthma is an important priority.

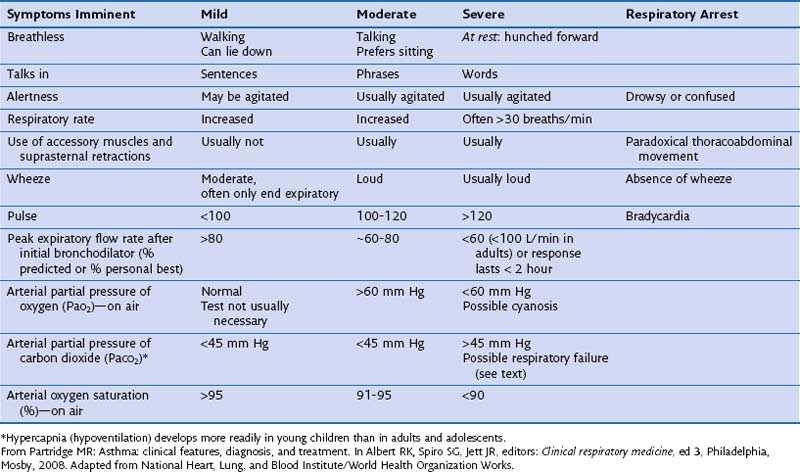

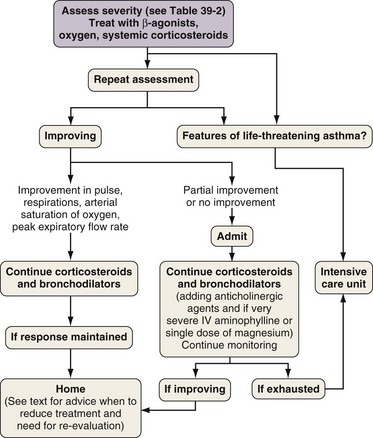

Asthma Attacks

People who have asthma die because they, their loved ones, or their doctors underestimate the severity, because of delays in seeking medical treatment, and because of underuse of oxygen and corticosteroid tablets. The severity of an exacerbation must therefore be carefully assessed, and the outcome determines the therapy given and the optimal treatment setting. Box 39-7 and Table 39-2 show features associated with exacerbations of asthma of mild, moderate, severe, or critical nature. All but the mildest attacks require treatment with bronchodilators, corticosteroids, and oxygen, with careful follow-up and assessment of responses to each intervention (Figure 39-12). Non–life-threatening asthma can be treated initially with four to six puffs of salbutamol from a pressurized metered dose inhaler (pMDI) with a large-volume spacer plus ipratropium, four puffs from a pMDI with large-volume spacer, both repeated as necessary every 10 to 15 minutes. A good response with symptom relief and an improvement in PEF to greater than 80% of the patient’s best is followed by continuing regular β-agonists every 4 hours for 24 to 48 hours, a four-fold increased dose of inhaled corticosteroids for at least 7 days, and careful review of the patient’s disease control status within days.

Box 39-7

Recognition and Assessment of Acute Severe Asthma in the Hospital Setting

Blood Gas Markers of a Very Severe, Life-Threatening Attack

Normal (36-45 mm Hg) or high arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2)

Severe hypoxia, with PaO2 less than 60 mm Hg irrespective of treatment with oxygen

NO OTHER INVESTIGATIONS are needed for immediate management.

From Partridge MR: Asthma: clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. In Albert RK, Spiro SG, Jett JR, editors: Clinical respiratory medicine, ed 3, Philadelphia, Mosby, 2008.

Figure 39-12 Algorithm for management of patient with acute severe asthma presenting for emergency care. IV, intravenous.

(From Partridge MR: Asthma: clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. In Albert RK, Spiro SG, Jett JR, editors: Clinical respiratory medicine, ed 3, Philadelphia, Mosby, 2008.)

A chest radiograph is indicated and should be performed if there is suspicion of additional intrathoracic pathology such as a pneumothorax or infective consolidation that will require additional therapeutic measures, if the patient fails to respond or deteriorates after initial therapy, or if the asthma attack is life-threatening or mechanical ventilation is being considered. If the blood oxygen saturation (SaO2) does not reach 92% with the patient breathing room air or if the PEF is less than 100 L/min, arterial blood gas analysis is indicated. Patients with features of severe disease (see Table 39-2) should be referred urgently for intensive care monitoring. The first warning of this level of acuteness may be a normal or raised arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) on blood gas sampling. Repeat blood gas sampling should be done in patients who are not clearly improving or appear to be deteriorating.

• The patient has been on discharge medication for 24 hours.

• Inhaler technique has been checked.

• PEF should be greater than 75% of predicted or better and PEF rate diurnal variability should be less than 25%, unless the patient’s respiratory physician confirms otherwise.

• Treatment with oral and inhaled corticosteroids in addition to bronchodilators has been prescribed.

• The patient has a PEF meter for home use, along with a written asthma action plan.

• Local follow-up evaluation has been arranged for within a week.

• A follow-up appointment in the chest clinic within 4 weeks has been scheduled.

Every attack of severe asthma and every hospital admission or emergency department visit must be regarded as a sign of failure of that patient’s previous asthma management. Patients presenting with acute severe asthma are at high risk for recurrent attacks and have a poor prognosis, often reflecting poor self-management skills. After successful medical management of the attack, a full review of the lessons that can be learned from the attack is warranted, and a self-management plan for the future should be formulated and communicated to the primary care physician. The most important elements of the management plan are illustrated in Figure 39-7.

Controversies and Pitfalls

Perhaps the most important pitfall is the failure to recognize “pseudoasthma” in a patient whose symptoms are not responding to escalating antiasthma therapy. Clinicians should repeatedly question the validity of the diagnosis in patients who are doing well and should actively seek objective confirmation of the presence of abnormal airway function or airway inflammation. This assessment should be capable of identifying corticosteroid-unresponsive phenotypes of asthma such as noneosinophilic asthma. Box 39-2 lists some features that should alert the clinician to an alternative explanation for asthma-like symptoms.

Summary

• Asthma is a clinical diagnosis that is made on the basis of the history and a demonstration of variable airflow obstruction.

• It is a syndrome, rather than a discrete entity; a growing interest in defining clinically important subgroups of asthma is influencing today’s research.

• Bronchial provocation testing with methacholine or histamine should be performed if diagnostic uncertainty remains in patients with normal spirometry findings.

• In patients with fixed airflow obstruction, it may not be possible to make a clear distinction between asthma and other related conditions, notably COPD. Assessment should focus more on defining mechanisms of airflow limitation, best achievable lung function, and optimal symptom control.

• Treatment goals for asthma are targeted at controlling symptoms, preventing asthma attacks, and preserving normal lung function.

• Asthma pharmacotherapy is broadly categorized into bronchodilator and antiinflammatory agents. These are currently prescribed in a stepwise manner with the primary aim of controlling symptoms.

• From 5% to 10% of patients have treatment-refractory asthma. Alternative or additional diagnoses should be sought in such cases. Newer therapies and different management strategies are being developed, but these agents have a limited spectrum of effects and are likely to work well only in certain subgroups. Assessment of airway inflammation is helpful in patients with severe asthma and may help identify patients who respond to these treatments.

Anderson GP. Endotyping asthma: new insights into key pathogenic mechanisms in a complex, heterogeneous disease. Lancet. 2008;372:1107–1119.

Brightling CE, Bradding P, Symon FA, et al. Mast-cell infiltration of airway smooth muscle in asthma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1699–1705.

British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. A national clinical guideline. British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Thorax. 2008;63:iv1–iv121.

Busse WW, Lemanske RFJr, Gern JE. Role of viral respiratory infections in asthma and asthma exacerbations. Lancet. 2010;376:826–834.

Douwes J, Gibson P, Pekkanen J, Pearce N. Non-eosinophilic asthma: importance and possible mechanisms. Thorax. 2002;57:643–648.

Haldar P, Brightling CE, Hargadon B, et al. Mepolizumab and exacerbations of refractory eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:973–984.

Haldar P, Pavord ID, Shaw DE, et al. Cluster analysis and clinical asthma phenotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:218–224.

Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:59–99.

Taylor DR, Pijnenburg MW, Smith AD, de Jongste JC. Exhaled nitric oxide measurements: clinical application and interpretation. Thorax. 2006;61:817–827.

Wenzel SE. Asthma: defining of the persistent adult phenotypes. Lancet. 2006;368:804–813.

British Thoracic Society/SIGN asthma guidelines. http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/c2/uploads/asthma_fullguideline2007.pdf.

Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2006 http://www.ginasthma.org

Occupational OASYS computerized occupational PEF software. http://www.occupationalasthma.com/occupational_asthma_pageview.aspx?id=4556.

Video of bronchial thermoplasty. http://www.nejm.org/search?q=bronchial+thermoplasty.

Asthma action plan resources. http://www.asthma.org.uk/all_about_asthma/publications/be_in_control_perso.html.