Chapter 4 Diagnosis

Introduction

A diverse range of clinicians practise CAM across the globe, each with varying levels of education and disparate methods of practice. While noticeable differences in service delivery are expected between CAM disciplines, there is no reason why CAM practitioners cannot practise consistently within each specialisation. A method to improve practice consistency within the field of CAM is DeFCAM (in particular, the application of diagnostic reasoning and the formulation of CAM diagnoses). The purpose and rationale for using CAM diagnoses in clinical practice is elucidated throughout this chapter, followed by examples of how these diagnoses can be structured and documented in order to ameliorate client care, enhance clinical outcomes and facilitate the professionalisation of CAM. First though, it is important to understand what the term ‘diagnosis’ represents.

Defining diagnosis

A diagnosis is a statement that identifies the nature or cause of a given phenomenon.1 What this definition highlights is that diagnosis is not a term limited to the healthcare sector, but a phrase used in any industry, including the automotive, engineering and computing sectors. One factor distinguishing a diagnosis made by a health professional to one formulated by a non-health-related discipline is the human element. Even though this element is shared by the health occupations, each healthcare profession interprets diagnosis differently. A medical diagnosis, for instance, is the identification of a specific disease or pathological condition based on a presenting pattern of signs and symptoms. By contrast, a nursing diagnosis is a statement that defines a human response to an actual or potential health problem that nurses can recognise and treat. A nutrition diagnosis is a ‘food and nutrition professional’s identification and labelling of an existing nutrition problem that the food and nutrition professional is responsible for treating independently’.2 The key point that emerges from each of these definitions is that diagnoses are profession-specific, that is, each profession has a particular knowledge base and skill set to competently formulate and treat specific types of diagnoses. In other words, while a nurse may be qualified to generate and treat nursing diagnoses, in most cases they would not be able to competently formulate or treat nutritional or medical diagnoses. Put simply, nurses make nursing diagnoses, dieticians make nutrition diagnoses.

Rationale for diagnosis

From an affirmative position, clinical diagnoses may help to focus a practitioner’s attention towards the cause of a client complaint. This argument supports one of the philosophical principles of CAM, that is, addressing the aetiology of the presenting condition. Through a better understanding of the cause of an illness, a clinical diagnosis can assist the clinician to create a more specific and pertinent treatment plan and, in effect, hasten the attainment of positive client outcomes. The treatment approach for an individual presenting with general fatigue, for instance, would be comparatively less specific, less individualised and potentially less effective than a plan for a client diagnosed with hypothyroidism and, as such, would inevitably hinder clinical progress. As well as the benefits to the client and CAM practitioner, clinical diagnoses can also help to improve interprofessional communication by providing a common language that is understood by most CAM and orthodox practitioners.

Factors affecting diagnostic accuracy

Other than the benefits mentioned above, clinical diagnosis also provides a clear and transparent link between assessment and treatment. It is not surprising, therefore, that misdiagnosis can lead to delayed or inappropriate clinical management and/or unnecessary disease progression that result in an increased risk of client morbidity and/or mortality. Even though the rate of misdiagnosis is uncertain in most countries due to the paucity of valid and reliable data, a German study of 100 randomly selected patients who died in hospital in 1999–2000 sheds some light; it reported a rate of misdiagnosis of eleven per cent.3 The global impact of misdiagnosis on all-cause morbidity and mortality has also been poorly investigated, although the social consequences are somewhat clearer, with more than twenty-one per cent of new public and private sector medical indemnity claims made in Australia in 2005–06 attributed to diagnostic error.4 Recognising and addressing the many determinants of diagnostic accuracy may help to minimise the risk of adverse events, as well as the subsequent risk of litigation against CAM practitioners.

Personal factors relate to practitioner self-confidence, beliefs, preferences, stress coping strategies and short-term memory capacity.5 The effect on clinical performance of alcohol, illicit drugs and/or excessive fatigue is a good case in point. A practitioner directly affected by these elements may, for instance, have difficulty retaining and processing information, which could lead to higher rates of diagnostic error and potentially delay client progress.

Among the extrinsic influences of diagnostic accuracy are the environmental elements. These refer to the availability of diagnostic resources, type of clinical setting, time constraints and interruptions or distractions. Resource access is a particular concern for most CAM practitioners, as many do not have access to subsidised investigations or have the skills or competencies required to perform these tests (at least not in Australia). Without access to certain investigations, or access to clinicians who have the capacity to perform these tests, some practitioners may have difficulty in establishing a diagnosis or determining the possible causes of the presenting complaint.

Adding to these factors are a number of elements that may further increase the risk of misdiagnosis in CAM practice, determinants that include limited access to diagnostic tools, variability of professional educational standards and limited interprofessional communication.6 The effect of training and education on diagnostic competency, in particular, has been recently highlighted in a survey of 617 Australian CAM practitioners. The study found that most clinicians used Western and CAM diagnostic techniques that they had received training in, except for the interpretation of pathological and radiological tests, of which one-third of practitioners had not received any training, even though they interpreted these tests in clinical practice.7 This is of concern, as adequate training is needed to develop sufficient competency in diagnostic skills8 in order to reduce the risk of misinterpretation and misdiagnosis.

Training in a variety of diagnostic tests has also been shown to be positively related to practitioner confidence in identifying clients requiring referral (p<0.05),7 which again highlights the probable association between inadequate education and increased risk of client harm. Thus, given that thirty-four per cent of patients were reported by Grace et al7 to have occasionally or never been assessed by a doctor prior to a CAM consultation, and that many CAM practitioners may not have the necessary skills, tools, confidence or competency to accurately diagnose or refer, suggests that some groups of clients may be at greater risk of being misdiagnosed and of receiving delayed or inappropriate treatment.

The process of diagnostic reasoning

Diagnostic reasoning, which is a ‘dynamic thinking process that … leads to a diagnosis that best explains the symptoms and clinical evidence in a given clinical situation’,9 may help clinicians to bridge the gap between assessment and diagnosis. Given that assessment and diagnosis are closely linked, however, with both steps informing each other, it is important to acknowledge that diagnostic reasoning is not a process limited to the third phase of DeFCAM, but it is another essential component of clinical assessment.

Guiding CAM practitioners through the process of diagnostic reasoning needs to take into account a number of important elements. Experience, for instance, is one factor that can influence the adopted style of diagnostic reasoning, as well as the quality of client outcomes. Even so, expertise takes time to acquire and, depending on the opportunities that present to the practitioner, experience may not necessarily lead to the development of an effective or efficient reasoning process. This is because a theoretical foundation needs to inform the process. Therefore, a factor that may greatly improve the outcomes of diagnostic reasoning, and one that does not discriminate between novice and expert clinicians, is the adoption of an appropriate critical thinking framework.

Apart from assisting CAM practitioners to better understand how healthcare professionals with different levels of expertise formulate clinical diagnoses, diagnostic reasoning models enable practitioners to recognise how to acquire, combine and process information to improve diagnostic accuracy,10,11 and thereby to solve clinical problems. In fact, Groves et al11 have shown that clinicians who follow a clear and streamlined diagnostic reasoning process and who interpret data correctly demonstrate greater diagnostic accuracy than practitioners who adopt a less efficient reasoning approach. The vast number of diagnostic reasoning models available to educators and practitioners of CAM (Table 4.1), as well as the frequent use of jargon within these frameworks, may make the selection of an appropriate model difficult.

| Bowen (2006) process12 | Data acquisition, problem representation, hypothesis generation, illness script selection, and final diagnosis |

| Clinical reasoning process (Groves et al 2003)11 | Identify relevant information, data interpretation, data integration, hypothesis generation, hypothesis testing, and working diagnosis |

| Clinical thinking process (Bates 1995)13 | Identify abnormal findings, cluster data, localise findings, interpret data, generate hypotheses, test hypotheses, and define problem |

| Diagnostic strategy (Murtagh 2007)14 | Determine probability diagnosis, potentially serious disorders, possible pitfalls, masquerading conditions, and patient hidden agendas |

| Hermeneutical model (Ritter 2003)15 | Pattern recognition, similarity recognition, common-sense understanding, skilled know-how, senses of salience, deliberative rationality, data gathering, and cue interpretation |

| Hypothesis-driven strategy (Szaflarski 1997)16 | Problem identification, hypothesis generation, hypothesis evaluation, hypothesis analysis, hypothesis assembly, and final diagnosis |

| Information processing model (Ritter 2003)15 | Data collection, further cue acquisition, formulation of possible solutions, problem identification, hypothesis generation, cue interpretation, and hypothesis evaluation |

| Nagelkerk (2001) process17 | Formulate competing diagnoses, order diagnostics, and select a diagnosis |

| Nursing diagnostic model (Perry 2008)18 | Data validation, data clustering, data interpretation, identification of client needs, and formulation of nursing diagnosis |

| Participative decision-making model (Ballard-Reisch 1990)19 | The diagnostic phase of the model consists of two stages – information gathering, and information interpretation |

| Zunkel et al (2004) model9 | Data collection, data synthesis, and hypothesis formation |

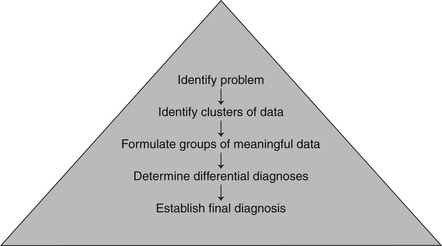

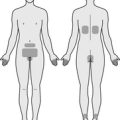

In order to simplify matters, diagnostic reasoning frameworks can be categorised into two main styles, that is, models based on inductive or deductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning, which guides the Hermeneutical, nursing diagnostic and Zunkel et al9 models, is a bottom-up reasoning approach by which specific data are developed into generalisations. As illustrated in Figure 4.1, the approach refers to the processing of specific symptoms and observations acquired during clinical assessment into meaningful clusters of information. These clusters are then continuously grouped into larger and more meaningful chunks of data until an appropriate diagnosis or range of differential diagnoses are generated. In clinical terms, this style of reasoning may progress as follows: succeeding the completion of a client assessment, specific symptoms such as pyrexia and malaise can be clustered together to represent any number of infectious or oncological disorders. When another cluster of data is added to the equation, such as dysuria and increased urine odour, the new chunk of information portrays greater meaning. In this example, the two clusters of data suggest that a urological condition may be present. Additional information from a urinalysis and urine culture can then be used to either support or dismiss a diagnosis of symptomatic bacteriuria.

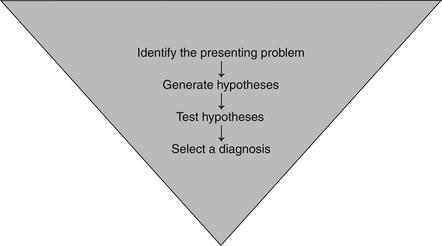

Deductive reasoning is by contrast a top-down method of reasoning whereby generalisations are narrowed down to specific conclusions, as illustrated in Figure 4.2. Models informed by deductive reasoning include the Murtagh14 diagnostic strategy, hypothesis-driven strategy and Nagelkerk17 process (see Table 4.1). When using this style of reasoning, a clinician formulates one or more hypotheses, or tentative diagnoses, and through critical enquiry – ‘if–then’ statements and emerging clinical data – tests whether the proposed diagnoses are probable or unlikely. This process of enquiry and the acquisition of additional data continues until a single plausible diagnosis is generated. The clinical application of deductive reasoning is exemplified as follows: a clinician assessing a client with fatigue may construct a range of hypotheses, including malnutrition, hypothyroidism and anaemia. The absence of pallor and shortness of breath, as well as a normal haemoglobin level, would eliminate anaemia as a possible diagnosis. Likewise, the consumption of a well-balanced, nutrient-dense diet, together with a normal comprehensive digestive stool analysis, would reduce the likelihood of malnutrition. The elimination of these alternative hypotheses and the presence of weight gain, depression and an elevated level of serum thyroid-stimulating hormone would point towards hypothyroidism as a highly probable diagnosis.

Some models, such as the clinical reasoning process, information processing model and clinical thinking process (see Table 4.1), use a mixed inductive–deductive reasoning approach. In these models, inductive reasoning is used to formulate differential diagnoses, from which a specific diagnosis is generated through deductive reasoning. Different variations to this approach are also evident.

Many studies have explored the diagnostic reasoning styles of novice and expert clinicians, with medical students, dentists, medical specialists and nurses being the few professional groups examined. What these studies reveal is that there are distinct differences in the way novice and expert clinicians acquire, organise, process and interpret data. Evidence suggests that expert clinicians are able to formulate correct diagnoses with comparatively less data and by ordering fewer tests than novice practitioners.20,21 Expert practitioners are also more inclined to use inductive or forward reasoning, whereas novices demonstrate a predilection for deductive reasoning.15,16 Improved organisation of ideas and evidence of a planned diagnostic strategy further distinguish expert clinicians from novices.20,21 Even though these findings may be discouraging for novice clinicians, it is possible that the path to diagnostic success may be hastened through the adoption of an organised diagnostic reasoning framework.

CAM diagnostic reasoning process

Even though a CAM practitioner may derive a conclusion about a presenting problem by using one of many structured diagnostic reasoning models, it is not clear which process may be best suited to CAM practice. What studies do highlight is that certain styles of diagnostic reasoning are correlated with greater diagnostic accuracy.21,22 In fact, after examining the clinical reasoning styles of twenty final-year ‘clinical clerks’ and twenty expert gastroenterologists, Coderre et al22 found the odds of diagnostic success when using inductive reasoning were 5.1 times greater (p<0.0001) than the odds of success with deductive reasoning, which was independent of expertise and clinical presentation. Comparable findings from a study examining the diagnostic reasoning approaches of beginner, competent and expert dentists21 adds to this body of evidence.

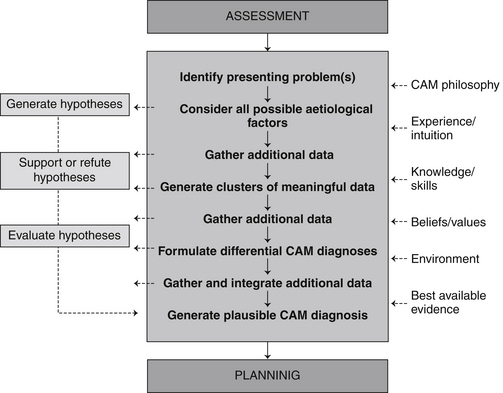

Even though there is some indication that frameworks adopting an inductive reasoning style may be most beneficial for clients and practitioners, and therefore to CAM practice, some of these models are poorly defined and, furthermore, make an assumption that practitioners already possess adequate skills in diagnostic reasoning. Hence, some of these models may not be useful to novice clinicians. Many existing frameworks also fail to take into consideration the myriad factors that influence CAM practitioner reasoning, including CAM philosophy, experience, skill, knowledge, intuition, the clinical environment, and client–clinician culture, beliefs, values and preferences. Another legitimate concern is that the process of diagnostic reasoning has been oversimplified in studies to date, as the style of reasoning used in clinical practice is likely to vary according to the complexity of the problem and the level of practitioner expertise.10 In some cases, multiple reasoning processes may be used simultaneously.15 A diagnostic reasoning model that uses a mixed inductive–deductive approach with a predominant focus on inductive reasoning that is also descriptive, user-friendly and applicable to CAM practitioners with diverse levels of expertise is needed. It is for these reasons that the CAM diagnostic reasoning approach was developed.

The CAM diagnostic reasoning approach consists of a central eight-stage inductive reasoning framework that sits alongside a three-phase deductive reasoning process. Informing the model (in no particular sequence) are six key influential factors of diagnostic reasoning, which are illustrated in Figure 4.3. Though the model appears to follow clinical assessment and precede the planning phase of DeFCAM, it needs to be acknowledged that the model is an integral component of clinical assessment, and thus both the assessment and diagnostic phases of DeFCAM should be viewed as interlinked, with assessment informing diagnosis and vice versa.

If a clinician decides to follow a path of deductive reasoning, they will continue to gather additional data in order to support or refute hypotheses until a final plausible diagnosis can be established. A CAM practitioner may then validate the selected diagnosis through a final evaluation of clinical data. If an inductive reasoning approach is followed, a clinician would need to gather enough information from the health history so that clusters of meaningful data can be generated. At this stage, a clinician would group together different combinations of often unconnected signs and symptoms to form clusters of information that may be indicative of different pathological states. Cough and pyrexia, for example, when clustered together can indicate the presence of a respiratory tract infection, yet, when cough and heartburn are grouped together, this may be suggestive of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. These clusters of information can then be ranked according to conditions that are ‘most probable’, ‘possible’ and ‘unlikely’. The collection of additional data from the physical assessment, and pathological, functional or radiological tests, and the generation of much larger chunks of information, enables the clinician to then formulate and rank a number of differential CAM diagnoses. Acquiring pertinent data to support or refute these diagnoses and integrating these findings with previously collected information enables the practitioner to isolate the most plausible CAM diagnosis.

CAM diagnosis

As highlighted earlier in this chapter, CAM diagnoses are client-centred statements that isolate actual or potential health problems and the aetiology of the problems that CAM practitioners can construct and manage. It is important that clinicians understand the structure and purpose of these statements, as they form an integral part of the CAM diagnostic reasoning approach. In order to appreciate the configuration of CAM diagnoses, it is useful to first examine the formula of other structured, profession-specific diagnoses, such as those used in nursing and dietetics.

Nursing diagnoses are three-part statements that consist of a possible, potential or actual problem, an aetiology and defining characteristics. For an individual with dehydration, a nurse may formulate the following nursing diagnosis: fluid volume deficit, related to vomiting and diarrhoea, manifested by poor skin turgor and increased pulse rate. Not dissimilar to nursing diagnoses are nutrition diagnoses, which also consist of a three-part statement, including an altered, impaired, ineffective, risk of, increased, decreased, acute or chronic problem, an aetiology and associated signs and symptoms.23 An example of a nutrition diagnosis is as follows: decreased energy intake related to anorexia, as evidenced by a BMI of 17.4 kg/m2 and a daily energy intake 4000 kJ less than recommended for age, gender and activity level. A key benefit of both of these approaches is that they help the clinician to focus on the cause of the presenting problem, which is compatible with the principles of CAM practice; in particular, the need to attend to the underlying aetiology of the condition.

One of the limitations of nursing and nutrition diagnoses that are not congruent with the principles of CAM practice is the problem statement. The fundamental issue with these statements is that they are clinician-centred, in that they serve to meet the wants of the practitioner over the needs of the client. Although a practitioner-centred approach, such as increasing fluid intake to address a fluid volume deficit, is likely to make a clinician’s decision about treatment easier, this approach detracts from what the client perceives as being most important to them, for example, the vomiting and diarrhoea. Given that individuals who perceive their care to be client-centred demonstrate comparatively better clinical outcomes and require fewer diagnostic tests and referrals than those who perceive their care not to be client-centred24 provides some justification for the need to adopt a client-centred approach. Other benefits, such as increased client responsibility, treatment satisfaction, quality of life and treatment compliance,25 add further support to the argument for client-centred care. One way to reinforce a client-centred approach in CAM practice is through clinical language, documentation and decision making, which DeFCAM and CAM diagnoses facilitate.

The development of CAM diagnoses emerged from a need to improve communication and documentation in CAM practice, as well as to improve efficiency, transparency and consistency of care. The need to improve client outcomes and to foster the professionalisation of CAM while remaining cognisant of the core principles of CAM (i.e. identifying the underlying cause of the presenting condition, preventing illness), provided further justification for the creation of CAM diagnoses. In order to meet these needs CAM diagnoses had to be clear, concise, objective, accurate and specific (see Table 4.2). These statements also needed to integrate the benefits of nursing and nutrition diagnoses noted above, yet had to be client-centred and relevant to CAM practice. The four-part structure of CAM diagnoses that has emerged is as follows.

| Accurate | Clear |

| Client-centred | Concise |

| Derived from assessment data | Integrates the biomedical perspective |

| Mindful of CAM principles | Objective |

| Rules out alternative diagnoses | Specific |

At the forefront of the CAM diagnosis is the client-centred problem, which is not only an integral part of the diagnostic reasoning process, but also helps to define the outcome measures of the planning and evaluation stages of client care. It is imperative then that a client identifies this problem as their most important concern because the problem identified will have major implications for the overall plan of care. A qualifier should accompany this problem in order to identify whether the complaint is actual or potential. This part of the CAM diagnosis enables practitioners to be more transparent and explicit about their involvement in preventative healthcare, which again supports the principles of CAM practice. The second half of the diagnosis focuses on the causes of the client’s complaint. The first of these are the secondary causes. This component identifies the medical diagnosis (e.g. diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, osteoarthritis), which serves to improve interprofessional communication, as well as understanding of the pathophysiological basis of the presenting complaint. The factors that are most likely to contribute to the development of the medical diagnosis and client problem are then recorded as primary causes (e.g. nutritional deficiency, vertebral subluxation, excess yang, kapha imbalance). These causes are expected to vary within and between professions due to differences in practitioner knowledge, skill, expertise, beliefs, resources, philosophy and diagnostic approaches. Specific examples of CAM diagnoses that may be observed in CAM practice are listed in Table 4.3.

Table 4.3 Examples of CAM diagnoses∗

| ACNE (actual), related to altered immune function, endocrine imbalance, high glycaemic load diet, nutritional imbalance, pitta imbalance, poor hygiene practices. |

| ANXIETY (actual), related to emotional stress, excess yang, life-changing event, hyperthyroidism, lactic acidosis, nutritional imbalance. |

| ARTHRALGIA (actual), secondary to osteoarthritis, related to elevated proteolytic enzyme activity, impaired cartilage formation, increased proinflammatory cytokine levels, joint misalignment, poor posture. |

| COLON CANCER (potential), related to cigarette smoking, inadequate frequency or duration of physical activity, inflammatory bowel disease, insufficient fibre intake, obesity. |

| CONSTIPATION (actual), related to chronic yin xu, decreased mobility, inadequate water intake, insufficient fibre intake, laxative abuse. |

| CORONARY HEART DISEASE (potential), related to cigarette smoking, hypercholesterolaemia, hypertension, obesity, sedentary lifestyle. |

| COUGH (actual), secondary to bronchitis, related to altered immune function, cigarette smoking, environmental irritants, excess yang, kapha imbalance, gastro-oesophageal reflux, impaired lung function. |

| DIARRHOEA (actual), secondary to irritable bowel syndrome, related to antibiotic therapy, emotional stress, food intolerance, intestinal dysbiosis, pitta imbalance. |

| DYSMENORRHOEA (actual), related to elevated oestrogen levels, elevated prostaglandin levels, emotional stress, nutritional imbalance, progesterone deficiency. |

| DYSPEPSIA (actual), secondary to gastric ulceration, related to anti-inflammatory medication, caffeine, cigarette smoking, food intolerance, Helicobacter pylori infection, impaired gastric mucosal integrity, obesity, pitta imbalance. |

| DYSURIA (actual), secondary to urinary tract infection, related to altered immune function, excess yang, impaired uroepithelial tissue integrity, inadequate water intake, poor hygiene practices, vaginal dysbiosis. |

| EARACHE (actual), secondary to chronic otitis media, related to altered immune function, environmental allergy, food intolerance, impaired mucous membrane integrity, nutritional imbalance. |

| ERECTILE DYSFUNCTION (potential), related to anxiety, neuropathy, nutritional imbalance, poor glycaemic control, vascular disease. |

| FATIGUE (actual), related to altered immune function, depression, emotional stress, hypothyroidism, kapha imbalance, neurotransmitter imbalance, nutritional imbalance. |

| FLAT AFFECT (actual), secondary to depression, related to chronic yang xu, emotional stress, hypothyroidism, insufficient sleep, life-changing event, neurotransmitter imbalance, nutritional imbalance. |

| HEADACHE (actual), related to dehydration, emotional stress, food intolerance, hypertension, physical stress or trauma, poor posture, vertebral subluxation. |

| HYPERCHOLESTEROLAEMIA (actual), related to cigarette smoking, excessive saturated fat consumption, obesity, oxidative stress, poor glycaemic control. |

| HYPERGLYCAEMIA (potential), secondary to type 2 diabetes mellitus, related to high glycaemic load diet, insufficient physical activity, insulin resistance, nutritional imbalance, obesity. |

| HYPERTENSION (potential), related to cigarette smoking, emotional stress, excessive sodium intake, excessive saturated fat consumption, obesity, poor glycaemic control. |

| INSOMNIA (actual), related to adverse environmental conditions, anxiety, chronic yin xu, emotional stress, hormonal fluctuations, medications, melatonin deficiency, nutritional imbalance. |

| LEG ULCERATION (potential), secondary to venous insufficiency, related to elevated proinflammatory cytokine levels, impaired capillary permeability, impaired venous integrity, increased proteolytic enzyme activity, oxidative stress. |

| MYALGIA (actual), secondary to fibromyalgia, related to abnormal sleep pattern, deconditioned muscles, emotional stress, impaired immune function, serotonin imbalance. |

| NASAL CONGESTION (actual) secondary to chronic sinusitis, related to emotional stress, environmental allergy, food intolerance, impaired immune function, kapha imbalance, poor mucous membrane integrity. |

| NAUSEA (actual), related to emotional stress, food intolerance, kapha imbalance, medication, pregnancy, vertebral subluxation. |

| NEPHROPATHY (potential), secondary to type 2 diabetes mellitus, related to cigarette smoking, hypertension, insulin resistance, poor glycaemic control. |

| NOCTURIA (actual), secondary to benign prostatic hypertrophy, related to chronic yang xu, elevated dihydrotestosterone, elevated oestrogen. |

| OBESITY/OVERWEIGHT (actual), related to increased energy intake, decreased energy expenditure, hypothyroidism, insulin resistance, sedentary lifestyle. |

| PARESTHESIAS (actual), related to heavy metal exposure, hypothyroidism, nerve entrapment, nutritional deficiency, poor glycaemic control. |

| PRURITUS (actual), secondary to eczema, related to elevated proinflammatory cytokine levels, emotional stress, environmental irritants, food intolerance, intestinal dysbiosis. |

| RETINOPATHY (potential), secondary to diabetes mellitus, related to cigarette smoking, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, insulin resistance, pitta imbalance, poor glycaemic control. |

| RHINORRHOEA (actual), secondary to allergic rhinitis, related to environmental allergy, elevated proinflammatory cytokine levels, food intolerance, kapha imbalance, nutritional imbalance, poor mucous membrane integrity. |

| SKIN LESION (actual), secondary to psoriasis, related to bowel toxaemia, elevated proinflammatory cytokine levels, impaired liver function, incomplete protein digestion, reduced cyclic adenosine monophosphate activity. |

| STROKE (cerebrovascular accident) (potential), related to cigarette smoking, hypercholesterolaemia, hypertension, obesity. |

| TINNITUS (actual), related to anaemia, atherosclerosis, emotional stress, excessive noise exposure, medication. |

| URTICARIA (actual), related to contact allergy, elevated proinflammatory cytokine levels, emotional stress, food intolerance, medications. |

| WHEEZE (actual), secondary to asthma, related to environmental irritants, food intolerance, kapha imbalance, nutritional imbalance, oxidative stress, sedentary lifestyle. |

∗ The diagnoses listed are examples only and should not be considered an exhaustive list. The phrasing of these diagnoses will also vary according to an individual’s presenting complaint.

The CAM diagnostic reasoning approach and the formulation of CAM diagnoses endeavour to improve the quality of care provided by CAM practitioners. A case example of how these approaches might be implemented in clinical practice is illustrated in Box 4.1.

Box 4.1 Application of the CAM diagnostic reasoning approach and the formulation of CAM diagnoses

Diagnostic reasoning

Gather additional data

Generate clusters of meaningful data

From the health history provided, the following clusters of meaningful data can be generated.

Summary

CAM diagnoses and the CAM diagnostic reasoning approach are integral components of DeFCAM. Apart from providing a link between assessment and planning, these processes assist clinicians in identifying the aetiology of the presenting problem at the same time as maintaining a client-centred approach that is compatible with the principles of CAM. Adding to this is the capacity to improve CAM communication, documentation and clinical practice and, in effect, client outcomes. It is through the generation of plausible CAM diagnoses and the achievement of these benefits that a CAM practitioner is then able to begin to adequately prepare an individual’s plan of care.

Learning activities

1. Parker P.M. Webster’s online dictionary. Fontainebleau: INSEAD; 2008.

2. Bueche J., et al. Nutrition care process and model part I: the 2008 update. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2008;108(7):1113-1117.

3. Kirsch W., Shapiro F., Folsch U.R. Healthcare quality: Misdiagnosis at a university hospital in five medical eras. Journal of Public Health. 2004;12(3):154-161.

4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Public and private sector medical indemnity claims in Australia 2005–06: a summary. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2007.

5. Anderson L. Exploring the diagnostic reasoning process to improve advanced physical assessments. Perspectives. 1998;22(1):17-22.

6. Bensoussan A., et al. Risks associated with the practice of naturopathy and Western herbal medicine. In: Lin V., et al, editors. The practice and regulatory requirements of naturopathy and Western herbal medicine. Melbourne: School of Public Health, La Trobe University, 2006.

7. Grace S., Vemulpad S., Beirman R. Training in and use of diagnostic techniques among CAM practitioners: an Australian study. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2006;12(7):695-700.

8. Seely D., Mills E. Diagnostic accuracy among the allied health professions: commentary on Grace et al. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2006;12(7):701-702.

9. Zunkel G., et al. Enhancing diagnostic reasoning skills in nurse practitioner students: a teaching tool. Nurse Educator. 2004;29(4):161-165.

10. Forde R. Competing conceptions of diagnostic reasoning: is there a way out? Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics. 1998;19:59-72.

11. Groves M., O’Rourke P., Alexander H. The clinical reasoning characteristics of diagnostic experts. Medical Teacher. 2003;25(3):308-313.

12. Bowen J.L. Educational strategies to promote clinical diagnostic reasoning. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(21):2217-2225.

13. Bates B. A guide to clinical thinking. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1995.

14. Murtagh J. A safe diagnostic strategy. In Murtagh J., editor: General practice, 4th ed., Sydney: McGraw Hill Medical, 2007.

15. Ritter B.J. An analysis of expert nurse practitioners’ diagnostic reasoning. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2003;15(3):137-141.

16. Szaflarski N.L. Diagnostic reasoning in acute and critical care. AACN Clinical Issues. 1997;8(3):291-302.

17. Nagelkerk J. Clinical decision-making in primary care. In: Nagelkerk J., editor. Diagnostic reasoning: case analysis in primary care practice. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001.

18. Perry A.G. Nursing diagnosis. In Crisp J., Taylor C., editors: Potter and Perry’s fundamentals of nursing, 3rd ed., Sydney: Elsevier, 2008.

19. Ballard-Reisch D.S. A model of participative decision making for physician-patient interaction. Health Communication. 1990;2(2):91-104.

20. Bloch R., et al. The role of strategy and redundancy in diagnostic reasoning. BMC Medical Education. 3(1), 2003. Accessed at <www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=149359 >, 28 January 2009

21. Crespo K., Torres J., Recio M. Reasoning process characteristics in the diagnostic skills of beginner, competent, and expert dentists. Journal of Dental Education. 2004;68(12):1235-1244.

22. Coderre S., et al. Diagnostic reasoning strategies and diagnostic success. Medical Education. 2003;37:695-703.

23. Lacey K., Pritchett E. Nutrition care process and model: ADA adopts road map to quality care and outcomes management. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2003;103(8):1061-1072.

24. Stewart M., et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. Journal of Family Practice. 2000;49(9):796-804.

25. Harkness J. Patient involvement: a vital principle for patient-centred healthcare. World Hospital Health Services. 2005;41(2):12-16. 40–3