4 Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Diabetes is a chronic disease defined by hyperglycemia caused by insulin deficiency. (Chapter 71 provides a detailed discussion of diabetes mellitus.). This may be the result of a lack of insulin production, as in type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) or the body’s ineffective use of the insulin it produces, as in type 2 diabetes mellitus. The most common form of diabetes in children is T1DM.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

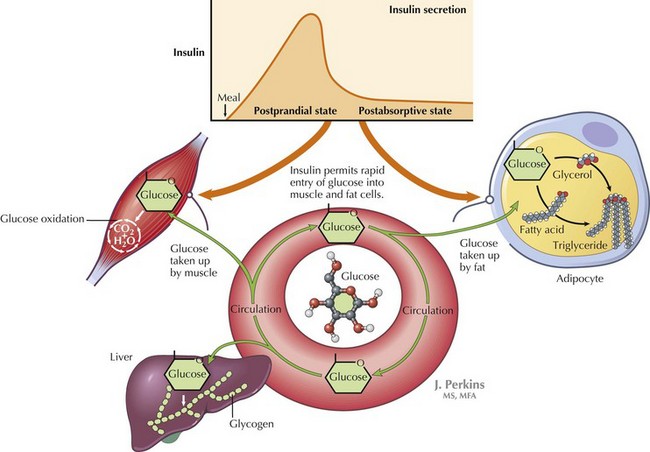

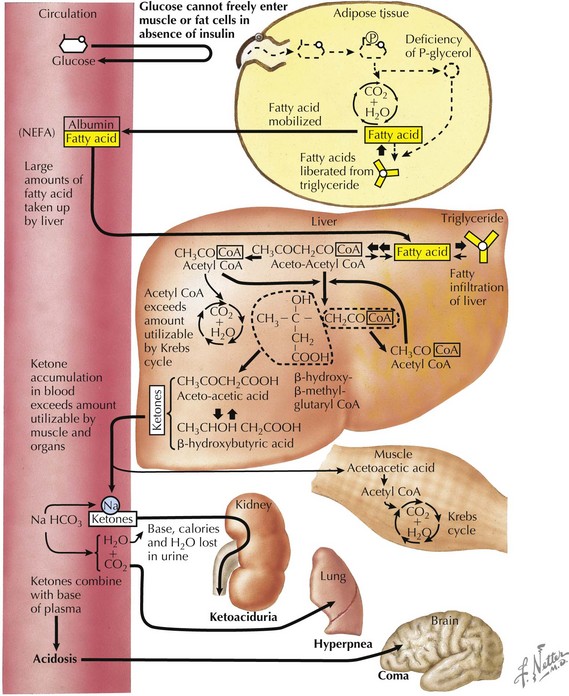

DKA is a result of insulin deficiency. Insulin is a hormone that responds to an increase in serum glucose via receptor-mediated utilization. This includes stimulation of glucose uptake from the blood by peripheral tissues; glycogen synthesis in the liver; and inhibition of processes that increase serum glucose, such as gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis (Figure 4-1). In the absence of insulin, blood glucose levels increase. There is inability to store glucose that is absorbed through the gut, and because of the absence of insulin’s suppression of these pathways, production of new glucose via gluconeogenesis continues. This process is perpetuated by increased production of hormones that increase blood glucose, including glucagon, cortisol, and catecholamines. As blood glucose increases, osmotic diuresis occurs, resulting in urinary losses of electrolytes. Because the body cannot use the glucose that has been supplied, it responds as if in the fasting state. Fat is then broken down into free fatty acids to be used as fuel. Free fatty acids are converted to ketoacids, including β-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate, leading to metabolic acidosis (Figure 4-2).

Clinical Presentation

Patients with DKA typically present with acute symptoms of nausea and vomiting. In patients presenting with T1DM for the first time, there may be a history of polyuria, polydipsia, enuresis, or weight loss. As ketosis progresses, patients may become obtunded and unable to provide a history. Therefore, a glucose measurement should be obtained quickly in any patient who presents with altered mental status. (Hypoglycemia may also be manifested as altered mental status.) Ketosis may also result in presence of a fruity breath, which can help direct the diagnosis. On physical examination, patients generally show signs related to the degree of dehydration from chronic hyperglycemia and osmotic diuresis. This may include tachycardia, presence of dry mucous membranes, and delayed capillary refill. DKA should be suspected in patients with signs of dehydration who maintain a high urine output. Abdominal examination often reveals diffuse tenderness. It is important to document a detailed neurologic examination at presentation because patients who present with normal mental status may have an acute change in status with therapy. DKA leads to physical examination findings affecting many systems (Table 4-1).

| Physical Examination Component | Findings | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| General | Can range from alert and interactive to obtunded based on the degree of dehydration and acidosis | Obtain a glucose measurement immediately on any patient presenting with altered mental status |

| HEENT | Dry mucous membranes, blurred vision, presence of fruity odor to breath | Ketosis tends to result in fruity odor to breath |

| Cardiovascular | Tachycardia | Indicative of dehydration |

| Lungs | Kussmaul respirations | Deep, sighing breaths used as respiratory compensation for metabolic acidosis Lungs are clear to auscultation, indicating the absence of an underlying lung pathology |

| Abdomen | Diffuse abdominal tenderness | Ileus may result from ketosis and can mislead the diagnosis toward an acute abdominal process |

| Extremities | Delayed capillary refill, decreased skin turgor | Indicative of dehydration |

| Intake and output | Increased | Indicative of thirst and increased fluid intake caused by osmotic diuresis |

HEENT, head, ears, eyes, nose, and throat.

Evaluation and Management

Dehydration

Management begins with an initial bolus of isotonic crystalloid fluid (hypotonic fluids should be avoided), usually 10 to 20 mL/kg of normal saline given over 1 hour. Initial fluid therapy is aimed at correcting the cardiovascular compensation for the degree of dehydration. Patients who present in shock may need more rapid fluid resuscitation. However, care must be taken not to administer too much fluid initially because of the risk of potentially fatal cerebral edema (see Complications). In general, the vital signs and clinical status should be reassessed between boluses of 10 mL/kg to avoid fluid overload. The goal is to gradually replace the fluid deficit over 36 to 48 hours.

Resolution

When pH and bicarbonate have normalized, ketones have decreased, and the patient feels well enough to begin to maintain hydration by mouth, treatment can be switched to a regimen of subcutaneous insulin. Because the half-life of IV insulin is several minutes, a subcutaneous insulin injection should be given before the insulin infusion is stopped. Management after DKA resolves is discussed in Chapter 71.

In patients with known T1DM, it is important to determine if DKA is the result of noncompliance with the demanding insulin regimen of several injections per day or with failure of insulin pump therapy (see Figure 71-2). Insulin pump therapy is designed to deliver subcutaneous insulin continuously with bolus dosing on demand. In these patients, it is important to emphasize compliance and education with current equipment.

American Diabetes Association. Available at http://www.diabetes.org

Cooke DW, Plotnick L. Management of diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adolescents. Pediatr Rev. 2008;29:431-436.

Glaser N, Barnett P, McCaslin I, et al. Risk factors for cerebral edema in children with diabetic ketoacidosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:264-269.

Sherry NA, Levitsky LL. Management of diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adolescents. Paediatr Drugs. 2008;10(4):209-215.

Vanelli M, Chiarelli F. Treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adolescents. Acta Bio Medica. 2003;74:59-68.

Weinzimer SA, Magge S. Type 1 diabetes mellitus in children. In: Moshang TJr, Bell LM, editors. Pediatric Endocrinology: The Requisites in Pediatrics. ed 1. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:3-18.