Diabetic ketoacidosis

How diabetic ketoacidosis develops

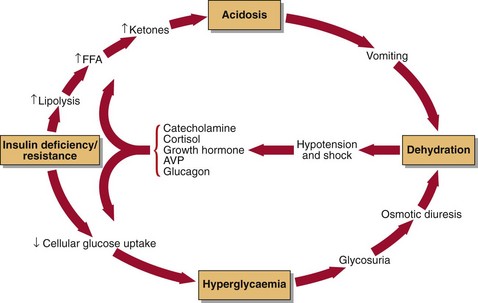

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a medical emergency. All metabolic disturbances seen in DKA are the indirect or direct consequences of the lack of insulin (Fig 33.1). Decreased glucose transport into tissues leads to hyperglycaemia, which gives rise to glycosuria. Increased lipolysis causes overproduction of fatty acids, some of which are converted into ketones, giving ketonaemia, metabolic acidosis and ketonuria. Glycosuria causes an osmotic diuresis, which leads to the loss of water and electrolytes – sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, phosphate and chloride. Dehydration, if severe, produces pre-renal uraemia and may lead to hypovolaemic shock. The severe metabolic acidosis is partially compensated by an increased ventilation rate (Kussmaul breathing). Frequent vomiting is also usually present and accentuates the loss of water and electrolytes. Thus the development of DKA is a series of interlocking vicious circles all of which must be broken to aid the restoration of normal carbohydrate and lipid metabolism.

Treatment

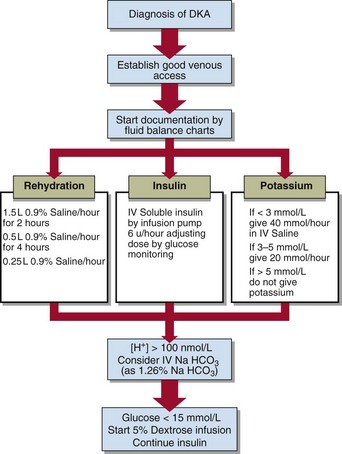

The management of DKA requires the administration of three agents:

Insulin. Intravenous insulin is most commonly used. Intramuscular insulin is an alternative when an infusion pump is not available or where venous access is difficult, e.g. in small children.

Insulin. Intravenous insulin is most commonly used. Intramuscular insulin is an alternative when an infusion pump is not available or where venous access is difficult, e.g. in small children.

Fluids. Patients with DKA are usually severely fluid depleted and it is essential to expand their ECF with saline to restore their circulation.

Fluids. Patients with DKA are usually severely fluid depleted and it is essential to expand their ECF with saline to restore their circulation.

Potassium. Despite apparently normal serum potassium levels, all patients with DKA have whole body potassium depletion that may be severe.

Potassium. Despite apparently normal serum potassium levels, all patients with DKA have whole body potassium depletion that may be severe.

The detailed management of diabetic ketoacidosis is shown in Figure 33.2. The importance of good fluid balance charts, as in any serious fluid and electrolyte disorder, cannot be over-emphasized. The initial high input of physiological (0.9%) saline is cut back as the patient’s fluid and electrolyte deficit improves. Intravenous insulin is given by continuous infusion using an automated pump, and potassium supplements are added to the fluid regimen. The hallmark of good management of a patient with DKA is close clinical and biochemical monitoring.

Laboratory investigations

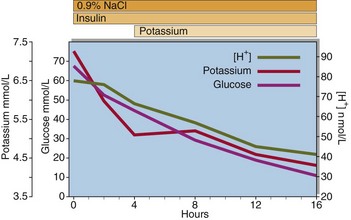

Blood glucose should be monitored hourly at the bedside until less than 15 mmol/L. Thereafter checks may continue 2-hourly. The plasma glucose should be confirmed in the laboratory every 2–4 hours. The frequency of monitoring of blood gases depends on the severity of DKA. In severe cases it should be performed 2-hourly at least for the first 4 hours. The serum potassium level should be checked every 2 hours for the first 6 hours, while urea and electrolytes should be measured at 4-hourly intervals (Fig 33.3).

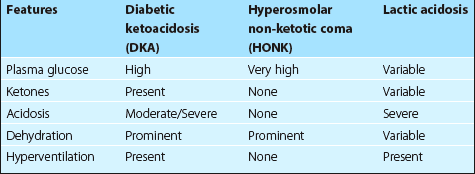

Two other forms of severe metabolic decompensation may occur in diabetic patients. These are hyperosmolar non-ketotic (HONK) coma and lactic acidosis. Table 33.1 shows the principal features of these conditions in comparison with DKA.