Chapter 6. Diabetic complications

Normal blood sugar control and the nature of diabetes 205

An overview of Type I and Type II diabetes 206

Infective complications in diabetes: the acute diabetic foot 242

Diabetes on the Acute Medical Unit: The General Approach

The illnesses to which diabetic individuals are susceptible will, in turn, have an adverse effect on diabetes control. Insulin requirements are increased in most acute medical conditions and diabetes control can become disrupted. Diabetic patients already on insulin may need careful adjustments: those not usually requiring insulin may need to have it introduced. Severe illness such as pneumonia or meningitis can even precipitate DKA. The level of short-term diabetes control may alter the longer-term outcomes in an acute illness. Recent evidence in acute myocardial infarction, for example, has shown that careful initial management of the blood sugars using an intensive insulin regimen can reduce the 1-year mortality rate by almost a third. There is increasing evidence that the same may be true in acute stroke: high blood sugars in the acute situation appear to have an important adverse influence on long-term stroke outcome. Clearly, the acute medical patient who is also diabetic can present some of the most taxing problems in terms of nursing and medical management.

The Acute Medical Unit nurse is presented with a dual challenge: to manage the primary acute medical problem and to ensure that the patient’s diabetes control does not have an adverse effect on the eventual outcome.

Diabetic emergencies, most notably ketoacidosis and hypoglycaemia, need immediate, expert management. Insulin-dependent diabetes can give rise to dramatic metabolic disturbances due to extreme changes in the blood sugar. The speed and accuracy of the initial assessment of the patient and the treatment in the first 2–3h of admission will have an important bearing on the prognosis. Box 6.1 lists the key points that should be checked in the acute admission of a diabetic patient.

Box 6.1

1. Is the patient hypoglycaemic?

2. Is this a diabetic emergency or an emergency in a patient with diabetes?

3. Confirm the timing of the last insulin/oral hypoglycaemic and the last meal

4. What is the usual regimen in this patient?

5. Critical nursing observations: GCS, pulse, blood pressure, temperature, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, blood sugar, urinary ketones

6. Check vision

7. Skin: examine pressure points (heels, soles of the feet, ankles), remove dressings

8. Look for infection: cellulitis (legs and feet)/groins/vaginal discharge?

9. Examine the feet: numb/painful/infected/gangrenous?

10. Urgent venesection for biochemistry, etc.

Diabetic individuals are prone to infections: healing is often impaired and extensive soft tissue damage and loss can occur. The feet, in particular, are at risk from acute infection as a result of the combination of diabetic neurological and diabetic vascular damage. Such infections often present as emergencies with spreading infection, uncontrolled diabetes and, in many cases, a lower limb at risk of amputation.

Finally, it is important to take advantage of the opportunities that can arise on the Acute Medical Unit to influence long-term management. In particular, there is an important link between poor compliance and the risk of diabetic complications. A significant proportion of patients with diabetes only seek medical advice when major problems arise. For these patients, their acute admission provides an important chance to look for unrecognised complications and initiate a review of their overall diabetes management.

Aims of this chapter

• To provide an understanding of normal and abnormal blood sugar control

• To present an overview contrasting Type I and Type II diabetes

• To examine the acute medical conditions that are associated with diabetes

• To explain how to control the blood sugars in adverse medical situations

• To present the management of diabetic emergencies

• To look at the treatment of infection in the diabetic patient

• To identify opportunities on the Acute Medical Unit to influence longer-term management

Normal Blood Sugar Control and the Nature of Diabetes

The normal blood sugar level is kept within the range 4mmol/L to 8mmol/L by a balance between:

• the rate at which glucose is removed from the blood to be used by the muscles

• the rate at which glucose is manufactured by the liver and released into the blood

Insulin is released from the pancreas and reduces the blood sugar by:

• increasing glucose uptake and utilisation by the muscles

• reducing glucose formation and release by the liver

Normally, the pancreas senses the increase in blood sugar that occurs after food is eaten and secretes a carefully controlled amount of insulin. The insulin lowers the blood sugar and drives metabolism by pushing glucose into the cells, where it is used for energy.

If there is no insulin present, the body behaves as though it is in a state of acute starvation:

• the liver compensates by producing and releasing excessive glucose

• the muscles stop taking in and using glucose

• as a result, there is an acute increase in the blood glucose level

• fat is burnt as the alternative source of energy to produce fatty acids. These, in turn, form ketones, which are acids. Ketones appear in the blood and the urine

• the patient becomes acidotic (the blood pH falls)

Diabetes occurs in two situations:

• there is a complete failure of insulin production. This is the situation in Type I diabetes

• there is a reduction in insulin production and the tissues themselves are resistant to the actions of insulin. This is the situation in Type II diabetes

An Overview of Type I and Type II Diabetes

Type I (or ‘insulin-dependent’, IDDM) diabetes mellitus occurs when there is a progressive failure of insulin production.

Type II (or ‘non-insulin-dependent’, NIDDM) diabetes mellitus occurs when there is a combination of two factors:

• the tissues fail to react to insulin

• the rate of insulin production is reduced

There are fundamental differences between the two types of diabetes (→Table 6.1).

• Type I diabetes

— there is little or no naturally occurring insulin

— unless supplied with regular carbohydrate and insulin, the patient will become ketotic

• Type II diabetes

— there is a relative lack, but not a complete absence, of insulin

— blood sugars are elevated, but the patient is not usually at risk from DKA unless triggered by severe illness such as acute pancreatitis

| Clinical onset | Natural insulin | Risk of DKA | Obesity | Relative frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Sudden | Nil | Yes | No | 20% |

| Type II | Slow | Low | Rare | 80% | 80% |

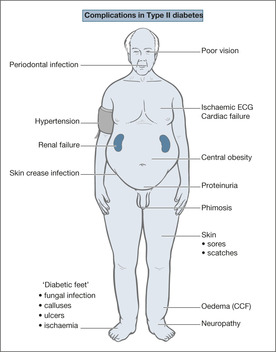

Type II diabetes

Type II diabetes is a partially inherited, age-related, ‘Western’ condition that has a strong association with obesity, a poor diet and physical inactivity. Insulin levels are moderately low (the number of pancreatic beta cells is reduced by around 20%). More importantly, the patient’s tissues are resistant to the action of insulin.

Recent Developments in the Treatment of Diabetes

Type I diabetes

There is increasing emphasis on tight blood sugar control to lessen the risks of long-term complications. In order to achieve this, there is a wide choice of insulin regimens and insulin injection devices. Many patients are now established on regimens with a basal background of single-dose, long-acting insulin that is fine-tuned by thrice-daily short-acting insulin regulated according to fingerprick blood sugar profiles. The importance of minimising postprandial increases in blood sugars has been realised and some patients use ultra-short-acting insulin (lispro/Novorapid®) with or even just after food to achieve this aim. New analogues such as insulin glargine and detemir are replacing isophane, the traditional basal insulin. Designed to be slowly released from the injection site, these insulins give a more physiological blood sugar profile and represent an important improvement in the management of Type I diabetes. Some patients are now fitted with an insulin pump – a Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion (CSII). This provides a basal infusion rate, which can be fine-tuned to alter throughout the day, and a bolus dose given by activating a button. In acute severe illness and DKA the pump should be disconnected and replaced with an intravenous insulin infusion. The dietary treatment of Type I diabetes remains based on an adequate calorie intake with complex carbohydrates, high fibre and a reduced fat intake.

Type II diabetes

Traditionally, management is based on dietary control with or without oral hypoglycaemics. The aims of dietary treatment in Type II diabetes are to reduce the energy intake, correct the blood lipids and reduce the patient’s weight. Drug treatment with oral hypoglycaemics acts by stimulating insulin secretion (e.g. glibenclamide and gliclazide), by re-sensitising the tissues to the action of insulin, or by directly reducing the release of glucose by the liver (metformin). In time, blood sugar control deteriorates – within 6 years of diagnosis, 25% of patients with Type II diabetes will require insulin. The effectiveness of combining once-daily insulin glargine or detemir with oral metformin has facilitated a much more active approach to blood sugar management, with the knowledge that this will improve the outlook.

Complications, in particular of vascular origin, are common in Type II diabetes. However, there have been major changes in our approach to their prevention. Up to 20% of new cases will have evidence of complications at the time of diagnosis and there is overwhelming evidence that the traditional ‘bad companions’ of diabetes have a major impact on the frequency with which they occur. Predictably, these are:

• hypertension

• hyperglycaemia

• hyperlipidaemia

• smoking

Large studies at the end of the 1990s have altered the perception of the importance of addressing these factors in patients with Type II diabetes. The evidence indicates that we must take every opportunity to re-enforce the need for good diabetic control and the need to reduce the other risk factors, notably hypertension and smoking. For example:

• Good long-term blood sugar control:

— reduces the risk of major diabetic eye disease by a quarter

— reduces the risk of early kidney damage by a third

• Lowering abnormally high blood pressure in these patients:

— reduces death from long-term complications by a third

— reduces the risk of strokes by a third

— reduces the risk of serious visual deterioration by a third

This represents a change of emphasis in management. The aim must be to keep the blood sugar and blood pressure in Type II diabetes as near normal as possible. The Acute Medical Unit often affords the first opportunity to address these issues, with both new and established diabetes.

Acute Medical Conditions Associated With Diabetes

AThe presence of widespread arterial damage in many diabetic patients makes them prone to a number of major acute medical problems. The cause of the damage is a combination of direct tissue toxicity from abnormally high sugar levels and the elevated blood lipids that are so common in diabetes. The effect of the damage depends on whether large (e.g. main coronary and cerebral arteries) or small (e.g. skin microcirculation and arteries within the kidney) vessels are predominantly affected (→Box 6.2). Unfortunately, in many of the older Type II diabetics there is damage throughout the arterial system, and these people are at risk from ischaemia affecting the coronary, cerebral and renal circulation.

Box 6.2

| Large vessel disease | Small vessel disease |

|---|---|

| Stroke Myocardial infarction Cardiac failure (coronary arteries) Amputation Sudden death (cardiac) |

Retinopathy (visual impairment) Renal failure (proteinuria/hypertension) Cardiac failure (heart microcirculation) Foot problems Sudden death (cardiac) |

Although there are no fundamental differences between the management of medical conditions in those with and without diabetes, diabetics as a rule fare less well than non-diabetics with the same disease. Thus diabetics with ischaemic heart disease have more widespread and more severe coronary artery disease and if they suffer infarct they have twice the mortality risk compared with non-diabetics. Complications are common, and often remain unrecognised by the patient. Thus a middle-aged patient with Type II diabetes may have heart muscle damage that only becomes apparent during other severe illnesses. Similarly, silent diabetic renal disease may lead to hypertension and its complications. It is therefore important that, when a patient with diabetes is admitted with a seemingly unrelated problem such as a urinary infection, the opportunity is taken to make a general assessment: for ischaemic heart disease, for hypertension and for kidney damage.

Tissues become damaged more easily and heal more slowly in diabetes. Immune function is reduced and organ damage is likely, especially where the blood supply is already compromised by diabetic vascular disease. Thus pneumonia is more likely to be complicated by empyema, renal infections may end in abscess formation and pressure sores may progress to osteomyelitis. Opportunistic infections may occur: examples include Candida infection of the skin creases and mucous membranes, pseudomonal infections of the ear and an unusual form of meningitis caused by the organism Listeria.

Diabetic renal disease

One-third of Type I and between one-quarter and one-half of Type II diabetic patients develop diabetic kidney disease (diabetic nephropathy). Diabetic nephropathy is the main cause of end-stage renal failure in the UK. Urinary protein loss is often the first indication of renal disease. Normally, we lose less than 30mg of albumin per 24h in the urine. An early sign that diabetes is affecting the kidneys is the presence of ‘micro’ albuminuria – a loss of 30–300mg per 24h – which can be detected using a specialised screening test. Once the protein loss exceeds 300mg per 24h, however, conventional testing of a random urine sample with Albustix® will be positive for protein. It is important to appreciate the significance of finding proteinuria in a diabetic patient on the Acute Medical Unit. It does much more than simply alert us to the possibility of a urinary infection.

• Proteinuria indicates probable renal involvement. (What are the patient’s urea and creatinine? Are there any previous records of kidney function in the notes?)

• Proteinuria goes hand-in-hand with cardiovascular complications and diabetic eye disease

• Proteinuria is strongly associated with hypertension

• Switching off the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (→p. 18) with ACE inhibitors (e.g. lisinopril) or angiotensin II receptor blockade (e.g. irbesartan) slows down the deterioration from microalbuminuria to advanced diabetic nephropathy.

If diabetic renal disease is discovered on the Acute Medical Unit for the first time, the patient must be referred on for specialist management so that the risk of further complications can be reduced by:

• careful blood pressure control

• treatment with ACE inhibitors and related drugs

• tight diabetic control

• correction of lipids

• advice on cessation of smoking

Diabetic neuropathy

Diabetic nerve damage is very common – it occurs in around one-third of patients with Type II diabetes. There are two types of diabetic neuropathy: peripheral neuropathy and autonomic neuropathy. Both are very relevant to the Acute Medical Unit nurse. Peripheral neuropathy gives problems in the feet: numbness, poor skin nutrition and impaired mobility. The patient has no warning of trauma to the feet, so minor abrasions can develop painlessly into infective ulceration. Nerve damage and muscle imbalance lead to foot deformity (claw toes) and pressure damage (calluses and ulcers) over abnormal bony prominences. Elsewhere in the body, nerve damage can lead to neuralgia with severe, recurrent and often undiagnosed pain in the thighs and abdomen.

Cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease is a major problem in diabetes and shortens the life expectancy of the diabetic patient by between 5 and 10 years. Diabetics with ischaemic heart disease have more widespread and more severe coronary artery disease than the non-diabetic. The main manifestations of cardiovascular disease are angina, myocardial infarction and heart failure. Due to diabetic neuropathy and an increased pain threshold, angina can present late and myocardial infarcts can be painless. It is not unusual for an infarct to present as a sudden deterioration in diabetic control. The risk of a myocardial infarct is increased in diabetes – by a factor of two to three in Type II diabetes and by an order of a magnitude in Type I diabetes sufficient, for example, to cancel out the protective effect of their sex in a premenopausal diabetic female. There is also increased mortality risk both in hospital and during long-term follow-up. The heart muscle fares badly in these patients and the risk of re-infarction is high. The strong association between diabetes and hypertension also accelerates many of the cardiovascular complications.

Cerebrovascular disease

The vascular damage in diabetes affects both the larger cerebral vessels and the cerebral microcirculation. Patients with diabetes are at two to three times the normal risk of having a stroke. Should they suffer one, the mortality risk is higher and the functional outcome is worse than the equivalent stroke in a non-diabetic. Diabetic cerebrovascular disease presents with typical stroke-like symptoms due to thrombosis or hypertension-related cerebral haemorrhage. It is critically important, however, not to misdiagnose a neurological presentation of hypoglycaemia as a stroke. It should be assumed that any change in the consciousness level of a diabetic patient has a metabolic cause until proved otherwise.

Peripheral vascular disease

Diabetic peripheral vascular disease presents as an emergency with ischaemic problems in the limbs due either to acute arterial occlusion or to vascular complications in the feet: ulceration, infection and gangrene.

Blood Sugar Control in Adverse Medical Situations

Assessing control

What are ‘osmotic symptoms’?

Heavy glycosuria draws water into the urine by osmosis. Osmotic symptoms are therefore polyuria and thirst, and are a sign either of the onset of diabetes or of diabetes that is out of control. The strength of the osmotic diuresis can lead to dehydration but also to electrolyte loss, most notably of potassium and sodium.

Laboratory blood sugar versus fingerprick testing

Although the fingerprick blood sugar tests give values that are around 15% less than the laboratory blood sugars, they are an invaluable way to assess diabetic control in the acute, unstable situation. The main problem is the unreliability of the glucose stix at low blood sugar levels. Normally, the BM stix is used as the initial test in suspected hypoglycaemia, so that immediate action can be taken. Ideally, blood should be drawn simultaneously for checking in the laboratory.

Modern blood glucose meters

Glucose meters and glucose test strips have improved considerably in recent years. At one time they were difficult to use and prone to user error: too little blood on the strip would lead to under-reading; timing had to be to the second; and the technique for wiping blood off the strip was critical. Fortunately, the manufacturers have removed many of the user-dependent problems that led to their unreliability.

Meters such as the Ascensia Control® and the Optium Xceed™ are popular because they are reliable, easy to use and require very small amounts of blood – some do not need calibration (Control), and some also measure blood ketones (Xceed). It is critical that the meters are used properly. There must be a Standard Operating Procedure in place, a training programme and a Staff Training Record.

• The new, ‘virtually’ pain-free, adjustable finger-pricking devices should be in used. The lancet should be enclosed in the removable platform of the device, making both sharps injuries and inadvertent re-use impossibilities

Good practice in fingerprick testing is outlined in Box 6.3.

Box 6.3

• Have you re-read the instructions recently?

• Has your machine been calibrated?

• Is the finger warm, dry and clean? Are your hands dry and clean?

• Prick the side, not the pulp, of the finger tips

• Produce a large drop of blood by milking up from the finger base

• Don’t let the skin touch the test strip

• Apply the drop to the strip so that it covers the test area – do not smear it on

• Follow the instructions

• If you have to, wipe or blot off the blood as instructed

• Use the meter as instructed

• Do you audit your practice?

• How do your results compare with the laboratory sugars?

• Is your ward’s blood glucose monitoring subject to a Quality Control Programme?

What about urine testing?

Urine testing for sugar is unreliable for both the diagnosis and the accurate monitoring of diabetes and has been largely replaced by blood sugar measurement. Normally, glucose spills over from the blood into the urine once the blood sugar is above 11mmol/L, but the level can vary from as little as 7mmol/L to as much as 15mmol/L. While it may be justified to monitor the occasional patient using urine testing, this would only apply to perhaps the very elderly diabetic who has been admitted to hospital with an unrelated problem and in whom frequent fingerprick testing would be considered unkind and unnecessary. In such a patient it would be reasonable to assume that, if there is little or no glycosuria, then the diabetes is probably under reasonable control. On the Acute Medical Unit the urine test for sugar is most useful as an initial screening test. If heavy glycosuria is found, it is important to look for ketones (see later).

What about one high blood sugar on admission?

By its nature, the blood sugar in most medical admissions will be a random one rather than fasting. Acute illnesses raise the stress hormones glucagon, adrenaline (epinephrine) and cortisone. Their actions counteract those of insulin. This may lead to a temporary diabetic state or may unmask latent diabetes. This effect can be exacerbated by some of the drugs that are used on the Acute Medical Unit:

• corticosteroids: especially dexamethasone or high-dose methyl prednisolone

• diuretics

Similar considerations apply to Type I diabetics. In particular, single injections of insulin to ‘bring the sugar down’ are usually unhelpful, as they obscure the pattern of diabetic control and are no substitute for planned management of the diabetes, taking into account the medical condition and the patient’s nutritional needs.

In summary: considerations when planning short-term control include:

• Is there a risk of ketosis?

• Will the blood sugar levels directly influence the medical outcome?

• Are there osmotic symptoms (thirst and polyuria) or dehydration?

• What are the risks and consequences of hypoglycaemia?

What is the importance of urinary ketones?

There are three types of ketones (also known as ketone bodies):

• aceto-acetic acid

• acetone

• beta-hydroxybutyrate

Ketones are acidic substances that appear in the blood when there is excessive breakdown of the body’s fat stores. They are used by muscle as an important source of energy when glucose is not available, either because of fasting or because there is no insulin available to drive glucose into the muscle cells.

In fasting states and in dietary glucose restriction, the ketone production is insufficient to cause an acidosis, and there is only mild or moderate ketonuria. This is in contrast to the situation in severe insulin deficiency, in which there is a large rise in blood ketone levels that can lead to a dangerous acidosis (→Box 6.4).

Box 6.4

| • Starvation (extreme dieting, vomiting) | – | small to moderate amounts |

| • Strict dieting in obese Type II diabetes | – | small to moderate amounts |

| • Diabetic ketoacidosis | – | moderate to large amounts |

It is vital for nurses to appreciate the difference between starvation (or vomiting) ketosis and DKA. This is a particular issue in the anorexic or dieting Type II diabetic who shows moderate ketonuria: do you rush in with a DKA regimen, or can you reassure the patient and even congratulate them on sticking so rigidly to their diet? This depends on the clinical picture. In general, ketonuria is much more likely to indicate impending ketoacidosis in the thin Type I diabetic than in the obese patient whose diabetes is controlled with oral hypoglycaemics. Moreover, the patient with ketoacidosis is likely to have warning symptoms: thirst, hyperventilation and nausea. The action the nurse would take is also dependent on whether or not there is an acidosis. A diabetic patient with moderate ketonuria may look ‘too well’ for DKA; check for acidosis. A simple venous blood sample for plasma HCO3 level will reveal if there is cause for concern: if the bicarbonate level is low (less than 15mmol/L) there is acidosis, if it is normal, then both nurse and patient can be reassured.

Case Study 6.1 illustrates difficulties with blood sugar control in a Type II diabetic. The main problem was steroid-induced hyperglycaemia without ketosis. Metformin is a commonly prescribed first-line oral hypoglycaemic and tends to be used in obese Type II diabetic patients. It was a reasonable choice in this case, although precautions have to be taken when it is used. The main problems concern the risk of lactic acidosis – a life-threatening metabolic disorder. There are a number of situations in which metformin is contraindicated because of this risk, some of which are relevant to the Acute Medical Unit:

• after a myocardial infarction

• in renal failure

• in severe liver disease

• in patients who are shocked or critically ill

• in patients more than 80 years old

• in patients who are having i.v. contrast studies

Case Study 6.1

A 42-year-old overweight woman was admitted with a 3-week history of severe thirst and polyuria. Her blood sugar was 34mmol/L and there were no ketones in her urine. Her blood pressure was 160/115mmHg.

She had chronic asthma controlled on inhaled corticosteroids. For 8 weeks she had needed high doses of oral steroids 20–30mg daily to control her worsening symptoms.

Treatment with metformin did not drop her sugars sufficiently nor did it clear her osmotic symptoms. She was therefore treated with short-term insulin while her asthma was controlled and her oral steroids were withdrawn. She was referred to the respiratory unit for review of her asthma and control of her blood pressure.

A blood pressure of 160/115mmHg is unacceptable in a diabetic patient since any level of hypertension in a diabetic is associated with accelerated vascular and renal disease. Aggressive blood pressure control reduces the risks considerably and in this patient a target level of 140/80mmHg would be entirely reasonable. It is likely that, once oral steroids were withdrawn from this patient, both her hyperglycaemia and her hypertension will settle. Short-term insulin was indicated mainly because of the marked osmotic symptoms.

Case Study 6.2 brings out more difficulties associated with the use of metformin in the elderly diabetic. The main problem here relates to the interaction of an acute medical illness and the patient’s oral hypoglycaemic drugs, rather than hyperglycaemia itself. This patient presented a complex problem of acidosis but not ketosis and renal failure (high urea and creatinine). The blood sugar was normal. Metformin has caused a lactic acidosis and the two diuretics have combined to produce profound abnormalities in the sodium and potassium levels. Drug side-effects are common in elderly patients, and particular care has to be taken in the case of elderly diabetics, who are prone to complicated acute medical problems.

Case Study 6.2

An 80-year-old man with Type II diabetes presented with a 3-week history of vomiting, breathlessness and diminishing mobility. On admission he was breathless and shivering. His mental test score was 4/10 and his temperature 37.4°C.

Treatment had been metformin 500mg tds, spironolactone 100mg bd, frusemide 80mg od and gliclazide 160mg bd.

On admission test results were:

BP 150/62mmHg

WCC 21.8 × 109/L

potassium 8.6mmol/L, sodium 120mmol/L, urea 38.2mmol/L, creatinine 251μmol/L, sugar 6.4mmol/L, bicarbonate 5mmol/L, urine: no glucose and no ketones

Practical Management of Diabetes in Adverse Circumstances

Several situations are encountered on the Acute Medical Unit in which it would not be appropriate simply to continue with the patient’s usual diabetic regimen and in which the management of the diabetes becomes an important practical problem:

• acute medical conditions that destabilise the diabetes

• acute medical conditions in which hyperglycaemia should be avoided

• diabetic patients who are unable to eat and drink normally

Type I diabetics need insulin at all times, whether they are eating or not; the acutely ill medical patient who is also diabetic is at risk from rapidly changing sugar levels and the development of ketoacidosis. In these patients it is important to ensure tight control with as simple a regimen as possible. Whether Type II diabetics require the same intensive approach depends on the severity of the medical condition, but in many acute situations due priority has to be given to the diabetic control, in addition to treating the immediate medical problem.

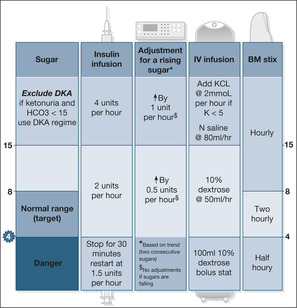

GKI or Glucose and a Sliding Scale?

There are two techniques that are used to control diabetes in the sick and unstable patient: the careful use of i.v. insulin and glucose, either as a single infusion (bag) containing glucose, potassium and insulin (GKI), or as separate infusions of dextrose and a sliding scale of i.v. insulin (→Box 6.5).

Box 6.5

| GKI | Sliding scale |

|---|---|

| • Simple to use | • Requires volumetric pump and syringe driver |

| • Risk of water overload | • Risk of hypoglycaemia |

| • Insulin + glucose together | • Suitable for complex fluid regimens |

In some hospitals, the sliding scale technique is thought to have several disadvantages compared with the simpler GKI ‘single bag’ infusion:

• the infusions are complicated to administer

• the dependence on separate infusions of insulin and glucose increases the risk of inadvertent swings in the blood sugar

The opposing view is that the advent of sophisticated infusion and syringe pumps has simplified their administration and minimised the risk of error. There are also advantages in having the flexibility of two adjustable infusions, particularly in critical situations in which there is a need for complex fluid regimens.

The safest approach is to use the regimen that is most familiar to the unit and which has been shown to be trouble-free during its use. Whichever regimen is favoured, the key is the attention to detail in setting up and running the regimen, combined with an appropriate level of monitoring.

In these patients, the DKA regimen (see later) should be followed, only changing to a GKI infusion (or dextrose and a sliding scale of insulin) once the sugar value is less than 13mmol/L.

Glucose-potassium and insulin

How to manage diabetes with a GKI infusion

The GKI infusion is the preferred way to control the blood sugars in a number of situations:

• the recovery period in DKA (i.e. once blood sugars fall below 13mmol/L)

• acute, severe illness in a non-ketotic diabetic patient (e.g. sepsis, stroke)

• post-myocardial infarction hyperglycaemia (once sugars fall below 13mmol/L)

• Type I diabetics who are nil-by-mouth (e.g. upper gastrointestinal bleeding awaiting endoscopy)

The intravenous infusion

• 500ml of 10% dextrose and 10mmol of KCl (omit the KCl if the serum potassium is more than 5mmol/L)

• add neutral insulin solution (Actrapid®) to the bag according to the blood sugar:

| blood sugar | 2.0–7.0mmol/L | add 8 units (1U/h) |

| blood sugar | 7.1–11.0mmol/L | add 16 units (2U/h) |

| blood sugar | 11.1–17.0mmol/L | add 32 units (4U/h) |

The doses of insulin may need to be reduced for each range of blood sugars if the patient is sensitive to insulin. Substitute doses of insulin for each range would be 4, 12 and 24 units.

Some types of patients need more insulin than usual:

• the extremely obese

• patients on steroid therapy (prednisolone, dexamethasone)

• cirrhosis

• previous high insulin doses, e.g. > 70 units per day

Some patients may need to have the scale ‘individualised’. In these situations, it may be necessary to consult with the diabetes team.

Target blood sugar. Aim for blood sugars in the range 7–11mmol/L.

Adjustments. Check and record the blood sugar with BM stix every hour. If it is necessary to change the insulin dose, make up and start a new bag, but do not change the infusion rate, which stays constant at 60ml/h.

Blood sugar more than 17mmol/L? Stop the dextrose infusion and start isotonic saline at 80ml/h. Check for urinary ketones and measure the venous bicarbonate. If this is not ketoacidosis, start a low-dose i.v. infusion of neutral insulin (Actrapid®) (see below) at 4 units per hour until the sugar falls to less than 17mmol/L for two consecutive hours. Then restart GKI.

Blood sugar less than 2mmol/L? Stop the GKI and give 10% dextrose 500ml at 60ml/h. Check the BM stix every half hour and restart GKI when the blood sugar increases to 4mmol/L. If the patient becomes clinically hypoglycaemic, seek urgent medical help and prepare to increase the strength of the dextrose infusion.

Hints on converting from i.v. infusions to subcutaneous insulin

• Once the patient is stable and able to eat and drink, change to subcutaneous insulin

• Change over in the morning, not at the end of the day

• Plan to give the first subcutaneous injection before breakfast

• If the patient is already on insulin, add 10% to their usual dose for the first few days

• If not previously on insulin, start on 30–40 units of neutral insulin solution (Actrapid®) divided into four doses

• Stop the insulin infusion 60min after the first dose of subcutaneous insulin (i.v. insulin disappears from the circulation in 5min)

How good is your subcutaneous insulin injection technique?

Insulin should be injected using an 8-mm needle by pinching up the skin and subcutaneous tissue (not the muscle) with thumb and index finger. The injection is given at right-angles (perpendicular) to the skin: ‘make a tent and put the insulin in through the front door’. The fold should be maintained throughout the injection and for 5–10s afterwards before the needle is removed. During the early hospital stay, the abdomen should be used (for the fastest rate of absorption and onset of action).

Note: The pinching technique does not apply to the new insulin pens, in which the preferred technique is a vertical injection into the skin.

Glucose infusion and a sliding scale of insulin

How to manage a diabetic with separate i.v. glucose and insulin infusions

Sliding scales are used in unstable patients to match the blood sugar with an appropriate dose of insulin. The insulin must always be administered with a source of glucose, usually 5% dextrose. The aim of a sliding scale is to keep the blood sugar under fairly tight control, while avoiding the risk of hypoglycaemia. The current practice is to use the scale with an adjustable i.v. infusion of insulin rather than with subcutaneous injections, as this gives smoother control. The technique would typically be used in unstable situations such as the critically ill diabetic patient and during recovery from DKA.

When using a sliding scale:

• there should be a dependable and constant supply of carbohydrate as i.v. glucose

• the insulin infusion rate should never be zero

• alter the whole sliding scale if the initial doses do not produce rapid control

• always overlap the infusion with the first dose of subcutaneous insulin by an hour

The glucose infusion. Give 5% dextrose 1L every 8h. If there is a history of cardiac disease, the volume of fluid should be reduced by using 10% dextrose 1L over 16h. Add potassium chloride to give 2mmol/h, provided that the serum potassium level is less than 5mmol/L. The potassium should be checked at least 6-hourly.

The insulin infusion. Make up an infusion of neutral insulin solution (Actrapid®) 50 units in 50ml of isotonic saline in a 50-ml syringe and driver. The initial hourly rate of insulin should approximate the patient’s usual insulin requirement. This can be estimated by dividing the total daily amount of insulin that the patient takes by 24. If this is not known or the patient has not previously been on insulin, estimate the required rate to be 3 units of insulin per hour.

Target blood sugar. The aim is to achieve sugar levels in the range 7–11mmol/L. Allowance may have to be made for any depot insulin already ‘on board’, onset of action of which may coincide with that of the sliding scale. Check the BM stix hourly while the patient is ill, then reduce to 2–4-hourly once the glucose is stable.

Adjusting the rate of insulin (the sliding scale). Adjust the rate of the insulin infusion (1 unit of insulin per hour is 1ml/h). The example given in Table 6.2 is for a patient who usually takes a total of 72 units of insulin per day (this is equivalent to an i.v. infusion requirement of 3 units per hour). Two sliding scales are illustrated, one with and one without sepsis, to emphasise the need to consider the influence of the underlying illness on the patient’s insulin requirements.

| Blood sugar (mmol/L) | Without sepsis (hourly insulin) | With sepsis (hourly insulin) |

|---|---|---|

| <4 | 1U | 2U |

| 4–6.9 | 2U | 3U |

| 7–9.9 | 3U | 4U |

| 10–13.9 | 4U | 5U |

| 14–17.9 | 5U | 6U |

| >17 | 6U and check for ketones | 8U and check for ketones |

Remember to alarm both the insulin and the dextrose infusions. If the sugars are 14mmol/L or less and the dextrose stops running but the insulin continues, there is a risk of hypoglycaemia.

Increase the insulin doses if there is likely to be insulin resistance. Keep the scale under review and if, 3–4h after starting insulin, the blood sugars remain out of control, the whole scale will need to be reviewed.

The DIGAMI regimen: an example of controlling the blood sugar in acute illness (→Fig. 6.1)

The DIGAMI study itself showed an important survival advantage in keeping sugars within the normal range in patients with acute coronary syndromes who are either known to have diabetes or whose blood sugar at the time of admission is more than 11mmol/L – findings that may be applicable to other groups such as those with acute stroke. The DIGAMI regimen is an excellent template for the practical approach to the close control of blood sugars in acute severe illness. In contrast to a sliding scale, the DIGAMI regimen uses the trend in capillary blood sugar to titrate the rate of administration of insulin, and may give smoother control.

Managing a case of severe medical problems and hyperglycaemia (→Case Study 6.3)

This is the story of acute severe pulmonary oedema with a preceding history of probable recent onset angina. Ischaemic heart disease complicated by a possible myocardial infarction is the most likely primary diagnosis. There is also a problem with the diabetes: the patient is on maximum oral hypoglycaemic therapy with two drugs, yet his doctor is still worried by recent blood results.

Case Study 6.3

A 55-year-old man was admitted at 04.00h with a 4-h history of increasing breathlessness associated with chest tightness and copious frothy sputum. He had been a diabetic for 5 years and took a combination of glibenclamide 15mg once daily and metformin 850mg twice daily. He was on no other medication. His family gave the additional history that for a month he had complained of chest discomfort on walking from his car to the office. He had also been concerned about his diabetes, his weight was increasing and his GP had not been happy with the results of his recent blood tests.

His skin, feet and pressure areas were all in good condition; there were no signs of infection.

Initial observations were as follows:

• pulse 150 beats/min and irregular

• blood pressure 80/50mmHg but difficult to hear

• temperature 37°C

• respiratory rate 30 breaths/min

• oxygen saturation on 35% oxygen: 88%

The patient was conscious and orientated, but was too breathless to speak.The fingerprick blood sugar was 28mmol/L. A small quantity of urine was obtained; this showed large amounts of sugar and protein, but no ketones.

Arterial and venous blood samples were taken.The patient’s ECG showed atrial fibrillation at 160 beats/min, with acute ischaemic changes, left ventricular enlargement, but no signs of an actual infarct. A portable chest X-ray confirmed pulmonary oedema.The oxygen was increased to 60%. He was given 80mg of i.v. frusemide and a small dose of i.v. diamorphine. He was started on subcutaneous low-molecular weight heparin.

By this time his blood tests were back:

• Blood gases

| — pH | 7.35 | not acidotic |

| — pO2 | 8.0kPa | should correct with increased oxygen |

| — pCO2 | 4.0kPa | normal (usually low in DKA due to hyperventilation) |

| – Bicarbonate | 19mmol/L | not acidotic |

• Biochemistry

| — sugar | 32mmol/L | high |

| — sodium | 144mmol/L | normal |

| — potassium | 5.1mmol/L | normal |

| — urea | 28mmol/L | high |

| — creatinine | 300μmol/L | high |

• The laboratory computer had some GP results from 6 weeks previously:

| — sugar | 19mmol/L | high |

| — urea | 24mmol/L | high |

| — creatinine | 280μmol/L | high |

| — HbA1c | 11% | high |

To bring the patient’s atrial fibrillation under rapid control, i.v. digoxin 0.75mg was given in 50ml of isotonic saline over 2h. To control the blood sugar, a low-dose insulin infusion of 50 units of neutral insulin solution (Actrapid®) in 50ml of saline was started at 3 units (3ml) per hour. After careful consideration, a urethral catheter was passed to measure the hourly urine output.

Two hours later, the patient was less breathless and felt more comfortable. His observations were as follows:

| • pulse | 110 beats/min |

| • blood pressure | 85/50mmHg |

| • respiratory rate | 25 breaths/min |

| • oxygen saturation | 95% |

| • blood sugar | 25mmol/L |

| • urine output | 20ml (negative for ketones) |

On this regimen,the blood pressure increased to 110/70mmHg and his urine output improved to 70ml/h.Once the blood sugars had decreased to 11mmol/L, the infusion was converted to a GKI. The patient continued to improve over the following 24h.

He was transferred to the care of the diabetic team to look at his cardiac status in more detail and to re-assess his long-term diabetic control. Subsequent enquiries confirmed that there had been concerns over previously elevated blood pressures of around 160/110mmHg, and that he had been considered for antihypertensive treatment ‘if the levels did not settle’.

The patient’s vital signs of hypotension, tachycardia and breathlessness are all in keeping with acute pulmonary oedema. However, DKA also can present like this. Although the blood sugar indicates that the patient’s diabetes is out of control, the absence of ketones in the urine is reassuring at this stage. It will be important to ensure further urine testing remains negative for ketones. The emergency laboratory blood results will also clarify the situation. The finding of heavy proteinuria without signs or symptoms of infection raises the possibility of diabetic kidney damage, which is characteristically associated with both generalised vascular disease and hypertension.

The investigations confirmed hyperglycaemia without diabetic ketoacidosis. There is mild renal failure. The GP results are helpful: the renal failure has not developed acutely and the patient’s diabetes has not been under good control. The HbA1c measures the amount of haemoglobin that has been linked to glucose in the blood: it has become an important indicator of diabetic control because it reflects the levels of blood sugars that have been occurring over the past 2 or 3 months. The higher the HbA1c, the higher the recent blood sugars. A ‘normal’ level of 7.5% or less in the absence of repeated hypoglycaemic episodes is an indication of good control. In this patient, the level of 11% confirms the suspicion of poor control. Reducing the level from 11% will have a progressive effect on reducing the risk of diabetic complications, particularly neuropathy, retinopathy and nephropathy. The immediate priorities are:

| • to clear the pulmonary oedema | (symptoms, saturations and respiratory rate) |

| • to slow the atrial fibrillation | (rate from cardiac monitor) |

| • to control the blood sugar | (hourly BM stix) |

Fluid balance will be critical:

• the patient’s heart may not cope with large volumes of fluid

• there is uncertainty about his renal function

• he may need multiple infusions (e.g. inotropic support or nitrates)

The interventions described in the case study resulted in some improvement in the patient’s pulmonary oedema and atrial fibrillation. The main problems were persistent hypotension, with a low urine output and continuing hyperglycaemia (but no ketosis). There was uncertainty as to whether or not the patient could be hypovolaemic. High blood sugars like these, particularly if they had been associated with an osmotic diuresis before admission, could have resulted in dehydration.

In summary, the patient in Case Study 6.3 presented with pulmonary oedema and atrial fibrillation due to ischaemic heart disease. These were complications of poorly controlled diabetes, diabetic renal disease and inadequately treated hypertension. His management illustrates how care must be coordinated and prioritised to address both the primary medical problems and the diabetes.

Could we (or Should we) Assess Obesity on the Acute Medical Unit?

At least 75% of all newly diagnosed NIDDM patients are obese, but this is difficult to quantify in the acutely sick patient. Nonetheless, weight loss of 10kg in this group will halve their fasting blood sugar, reduce diabetes-related death rates by a third, drop their diastolic blood pressure by 20mmHg, and cut their cholesterol by 10%.

Patients with a BMI (weight/height2) of more than 30kg/m2 have significantly increased health risks. Similar considerations apply to waist circumference, which is a lot easier to measure in the acute situation: high risk is associated with waist circumferences greater than 102cm in men and 88cm in women.

Management of Acute Diabetic Emergencies

DKA

A reasonably sized district general hospital can expect to admit around two cases of DKA per month. Most will be of moderate severity, but a few patients will be severely ill. Among this population will be the brittle diabetics with recurrent ketoacidosis and often with a history of poor compliance.

Causes of DKA (→Box 6.6)

Most cases of DKA are precipitated by infection or some form of disruption to the insulin treatment. This is often due to inappropriate action taken by the patient at the time of an acute illness: usually stopping or reducing insulin because of problems with maintaining oral intake. An important minority of cases of DKA are the first manifestation of new-onset diabetes. There will also be a number of brittle diabetics with recurrent ketoacidosis – predominantly female, socially disadvantaged and poorly compliant, this group often have associated eating disorders. Recently, an increasing problem of ketoacidosis in Type II diabetes is being recognised, particularly in patients of Afro-Caribbean origin. Interestingly, once the episode is over, these patients can return to oral hypoglycaemics or even to dietary treatment alone.

Box 6.6

| Infection | 40% |

| Disruption of insulin treatment | 25% |

| New-onset | 15% |

| Other causes (e.g. infarct, pregnancy) | 20% |

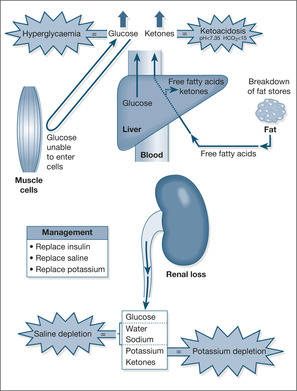

Underlying mechanism

In DKA there is an acute shortage of insulin. As a result, the liver produces and releases excessive amounts of glucose that appear in the blood (hyperglycaemia) and which spill over into the urine (glycosuria). The heavy glucose load in the urine pulls in water and electrolytes by osmosis, leading to losses of fluid (dehydration), loss of potassium (hypokalaemia), and losses of sodium (hyponatraemia), phosphate and magnesium. Because there is a shortage of insulin, sugar cannot enter the cells and so the body starts to burn adipose tissue (fat stores) as an alternative energy source. The adipose tissue breaks down to free fatty acids, which are in turn converted into ketones by the liver. Some of the ketones are used by muscles for energy and some are excreted in the urine (urine positive for ketones). Ketones are acidic substances, so when excess ketones appear in the blood they produce an acidosis. The ketones can be smelt on the breath and measured in the blood and the urine using Ketostix® on serum (a simple clotted blood sample) and on fresh urine. The consequences of DKA are illustrated in Fig. 6.2.

Management

The key to treatment of DKA should be clear from the above discussion:

• adequate insulin replacement

• correction of fluid and electrolyte loss

Acidosis does not usually need correcting, as it responds to the reversal of the ketosis by insulin, fluid and electrolyte therapy. Case Study 6.4 describes a case of acute severe DKA.

Case Study 6.4

A woman who had been a diabetic for 30 years, now aged 50, was admitted with a 48-h history of anorexia, headache and breathlessness. Her blood sugar the day before admission was 17mmol/L. Her husband usually administered her insulin and she had good control, with blood sugars in the range 3–5mmol/L on twice daily isophane 9 and 7 units and morning soluble 5 units. After a domestic upset, there was some doubt about whether she had received her insulin on the day of admission to hospital. Her husband came home from work to find her nearly unconscious and hyperventilating.There had been one previous admission with DKA 5 years before.

On examination the patient was apyrexial, respiration rate 40/min, pulse 110 beats/min and blood pressure 90/60mmHg. Oxygen saturations were 99% on air. She was restless and aggressive. Her GCS was 9/15. Examination was otherwise negative, apart from generalised abdominal tenderness. Her breath smelt of ketones.

The ECG showed signs of an acutely raised potassium level.The urine showed large amounts of ketones, protein and sugar. BM stix was 55mmol/L.

Blood samples, including blood cultures, were sent for analysis, and an immediate injection of calcium gluconate was given intravenously. A central line, nasogastric tube and urethral catheter were passed. A portable chest radiograph was performed.

The following test results came back:

| • Hb | 12.9g/dl | normal |

| • WCC | 29.7 × 109/L | very high as is common in DKA, even if infection is not present |

| • Glucose | 58.7mmol/L | very high (DKA can occur at sugars as low as 12mmol/L, but most are >25mmol/L) |

| • Sodium | 127mmol/L | low due to sodium lost in the osmotic diuresis |

| • Potassium | 8.6mmol/L | very high; the total body potassium is low, however, and the level will fall rapidly with treatment (known as ‘hidden’ potassium loss) |

| • Urea | 14.2mmol/L | high due to dehydration |

| • Creatinine | 226μmol/L | high due to dehydration (normal when tested 3 months prior to admission: always check previous notes for pre-existing kidney function) |

| • pH | 6.93 | severe acidosis (most patients with DKA will have a pH of 7.0–7.2) |

| • pO2 | 21.6kPa | good oxygen levels (on oxygen therapy) |

| • pCO2 | 1.6kPa | low (blown off by hyperventilation) |

| • Bicarbonate | 2.0mmol/L | low (this increases as the acidosis improves with treatment) |

INSULIN THERAPY

Twenty units of neutral insulin solution (Actrapid®) was given intramuscularly immediately, while an infusion was being prepared and the syringe pump set up. The infusion consisted of 50ml of 0.9% (normal) saline with 50 units of neutral insulin solution (Actrapid®).This was i.v. at a rate of 6 units (6ml) per hour. After 6h, the sugar had fallen to 13mmol/L; the insulin infusion was stopped and replaced by a GKI infusion.

INTRAVENOUS FLUID REPLACEMENT

• 2L of isotonic saline were given in the first hour (via an infusion pump)

• 1L of isotonic saline was given in the second hour

• 500ml/h of isotonic saline was then given for 4h

• The GKI infusion was started at 6h and the saline discontinued

By 24h, the patient was feeling well, her urine was showing moderate amounts of ketones only, and she was starting to eat normally. Subcutaneous insulin was re-started at that stage, ensuring a 1-h overlap with the GKI infusion.

POTASSIUM REPLACEMENT

• Potassium was added to the infusion at 20mmol/h once the serum potassium had fallen to less than 5.0mmol/L

BICARBONATE

• 100mmol of sodium bicarbonate (600ml of 1.4% sodium bicarbonate) was given through the central line over 30min

MONITORING

• Hourly BM stix were continued until the patient could eat and drink normally

• Hourly pulse, BP, temperature, respiratory rate, GCS and urine output until the patient was stable (at least 6h)

• Hourly oxygen saturations and supplementary oxygen to keep the saturations above 94%

• 2-hourly potassium, sugar, sodium, urea and bicarbonate until the sugar had fallen to 13mmol/L

• A flow diagram was used to show the progress of the blood tests

• Urinary ketones were checked every 2h (note that the ketonuria frequently increases initially and may take at least 24h to clear from the urine)

• Continuous ECG monitor for 24h (the risk of hyperkalaemia and arrhythmias)

Hyperventilation is a sign of acidotic breathing (the body is trying to correct the acidosis by blowing off carbon dioxide). The patient in Case Study 6.4 had not been eating for 2 days and was therefore at risk from ketosis. Missing a single dose of insulin would have been enough to accelerate the onset of ketosis.

The patient had signs of DKA with hypovolaemia (low blood pressure). There were no features of infection. In particular, the chest was clear, there was no skin sepsis and there was no renal angle tenderness. There was no sign of meningeal irritation. Abdominal pain and tenderness are common features in DKA and can be due to acute fatty liver infiltration or pancreatitis. The patient was able to protect her airway (GCS above 8).

Hyperkalaemia is common in DKA, but there is usually a rapid fall as soon as fluids and insulin are given and the potassium enters the cells. Normally, we would administer potassium with the second litre of fluid. In this case, however, there were changes on the ECG showing that the high potassium level was putting the heart rhythm at risk. Urgent action was needed to bring the level down. The patient was going to need careful fluid balance – hence the central line and catheter. The nasogastric tube was to prevent aspiration of stomach contents in the event of acute gastric paralysis with distension, a common problem in severe DKA.

The importance of fluid balance in nursing the diabetic patient

Nurses must be exceptionally careful monitoring the input and output in acutely ill diabetic patients. In DKA and non-ketotic hyperglycaemia, high volumes of fluid are being given to patients who are in a critical state because of fluid depletion amounting to between 4 and 6L. However, these patients may well have both cardiac and renal problems due to their diabetes and are at risk from fluid overload. This is critical in the first few hours of admission: typically, a patient with severe DKA may not pass urine for the first hour or two of rehydration, but if this persists they may need catheterisation and even a central venous line to ensure that the fluid input is not overly aggressive. Some DKA protocols recommend 2L of fluid in the first hour, but this would be too fast for the frail, elderly and those with heart disease. Moreover, over-enthusiastic fluid replacement will wash out ketones and lower the blood sugar, but paradoxically lead to a worsening of the acidosis. An example of judicious fluid replacement of, say, a 7L deficit (severe dehydration) in a frail patient would be:

2L isotonic saline over 4h

1L isotonic saline over 4h

0.5L isotonic saline over 8h

the remaining 3.5L over the next 24h

What to avoid while treatment is working

Hypokalaemia. Patients with DKA may start with a high potassium, but the level drops rapidly once the potassium moves back into the cells when insulin is given. Potassium supplements are usually added to the second litre of saline and continued at 20mmol/h. Adjustments to the rate of potassium replacement can be made according to the 2-hourly potassium results. An example of the way to adjust the potassium supplements is shown in Table 6.3.

| Potassium level in the blood (mmol/L) | Potassium added to each litre of saline (mmol) |

|---|---|

| <3.0 | 40 |

| 3.0–4.0 | 30 |

| 4.0–5.5 | 20 |

| >5.5 or anuric | Nil |

Hypoglycaemia. Start GKI as the sugar falls to 13mmol/L.

Fluid overload. The overall fluid deficit will be between 4 and 6L. In a sick diabetic patient it is wise to use a central line and monitor the CVP. Any infusion should be controlled with a volumetric pump.

Aspiration. Care of the patient with altered consciousness. Empty the stomach contents with a nasogastric tube if necessary.

Intracerebral oedema. This grave complication is unusual and tends to occur in those patients less than 20 years old. It usually occurs during the first 24h after initial apparent metabolic and clinical improvement. There is a sudden deterioration in the consciousness level (fall in the GCS) with neurological signs such as severe headache, neck stiffness, fitting and bilateral up-going plantars. It may be seen with over-enthusiastic fluid replacement (in these cases the blood appears diluted and the sodium level falls below normal, e.g. to 120mmol/L) or it can simply occur for no obvious reason in a severe DKA. Diagnosis is by CT scan (and excluding meningitis or stroke) and treatment aims to reduce the raised intracranial pressure with mannitol (100ml of 20% mannitol over 20 minutes) and dexamethasone.

A management protocol for DKA

Fluid replacement

1. 2L of isotonic (0.9%) saline in 4h

2. 2L of isotonic (0.9%) saline in 8h

3. 2L of isotonic (0.9%) saline in 16h

Increase the rate if:

• there is persistent hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90mmHg)

• the urine output is very high

Reduce the rate if:

• the patient is elderly and frail

• there is a risk of heart failure (e.g. previous left ventricular failure, ankle oedema)

Consider hypotonic (0.45%) saline only if:

• the sodium level climbs above 155mmol/L

Potassium

• Give 20mmol of KCl per hour once the potassium level is known (the KCl will therefore usually start with the second litre)

• Do not give KCl while the potassium level is more than 5.5mmol/L

• Check the potassium level in the blood every 2h

Insulin

• Give 20 units of neutral insulin solution (Actrapid®) intramuscularly as soon as DKA has been recognised

• Follow with an insulin infusion at 6 units/h (50 units in 50ml at 6ml/h)

• Follow the response with hourly BM stix and 2-hourly laboratory sugar testing

If there is no fall in the blood sugar at 2h:

• check the i.v. lines and the pumps (the most common cause for a ‘failure’ of i.v. insulin therapy)

• double the insulin infusion rate

• double again if no further fall at 4h

The blood sugar should fall at around 5mmol/h. If the fall is too rapid,

• reduce the insulin infusion rate

When the sugar falls to 13mmol/L

Blood sugar

Insulin

10% dextrose

>14

6u/h

Nil

9–13.9

3u/h

100ml/h

<9

2u/h

200ml/h

• Continue hourly BM stix and 4-hourly urinary Ketostix®, but reduce the laboratory measurements

• Start a GKI infusion aiming for sugars in the range 7–11mmol/L

• Alternatively, continue saline (as fluid replacement) and the insulin infusion at 3 units per hour and add 10% dextrose, 100ml per hour, through a separate cannula. An example of adjustments to the insulin and dextrose is given in Table 6.4 below:

When the patient can eat his first meal

• Change to subcutaneous insulin

• Ensure a 1-h overlap between the GKI infusion and the first injection

When to use sodium bicarbonate

• Only when there is severe acidosis and hypotension: pH < 6.9

• Give 600ml of 1.4% sodium bicarbonate with 20mmol KCl over 30min

• Check gases after 30min and repeat the dose if pH is < 6.9 and hypotensive

• Avoid extravasation with sodium bicarbonate: use a central line if possible

General care

• Catheterise if no urine has been passed within 3h or if there is hypotension

• Insert nasogastric tube if the consciousness level is disturbed (GCS less than 8)

• Administer broad-spectrum antibiotics if sepsis is suspected (e.g. co-amoxiclav and cephalexin)

• Administer low-molecular weight heparin if there are risk factors for venous thromboembolic disease (→Box 6.7)

Box 6.7

• No contraindication

• Severe DKA

• Previous thromboembolism

• Hyperosmolar

• ‘Phlebitic’ legs

▪ Is the airway safe?

▪ Oxygen saturation

▪ Blood sugar

▪ Blood pressure

▪ Pulse (ECG)

Nursing the patient with DKA

The first 4–5h are critical in the care of the patient with ketoacidosis. The nurse will be caring for a very sick, distressed and possibly confused patient going through a period of intense clinical activity. The nurse will be combining the technical expertise necessary to administer a complex treatment regimen and the skills required to meet the personal needs of a patient who is vulnerable, who feels dreadful and who is probably terrified for his life.

Critical nursing tasks in DKA

Ensure that the initial infusions are correctly prescribed and administered

It is vital that there is absolutely no delay in initiating the saline and insulin infusions. The protocol must be followed and the correct amounts of fluid given during the first critical few hours. Particular attention must be paid to the potassium supplements and the subsequent blood levels.

Monitor the patient’s progress

The hourly observations should chart: a falling pulse, rising blood pressure and increasing urine output as dehydration is corrected. If there is confusion or impairment of the consciousness level, the GCS will improve. As acidosis resolves, the respiratory rate will fall and symptoms will improve. The sugar should fall at around 5–10mmol/L per hour. The potassium should settle between 3.5 and 5.5mmol/L. Urinary ketones will slowly disappear over 18–24h and the appetite will return.

Address the patient’s physical needs

If the patient is unconscious, the priority is the nursing care of coma. The patient may be in discomfort and possibly in pain. If this is severe, a judgement will be made about the need for effective analgesics. The patient should adopt a comfortable position in bed and due attention should be paid to the pressure sites, in particular to the heels. Mouth care will be important because hyperventilation and dehydration will dry out the oral mucosa. There will be nausea, so sucking ice may be preferable to oral fluids. During the first few hours of admission there will be numerous medical and nursing interventions performed, so the patient’s physical comfort will need to be continually reassessed.

Provide reassurance and support

Initially the patient may feel frightened and powerless. Patients with long-standing diabetes may be worried about relinquishing control to nurses and medical staff who are not part of the usual diabetic team. These fears will need to be addressed and the patient reassured about the temporary need for intensive insulin and fluid therapy. If there is disorientation or confusion, the patient will need support and explanation as the situation improves.

Initiate plans to prevent this from happening to the patient again

If your communication and assessment have been effective, it should be clear why this has happened. Involve the diabetes specialist nurse at an early stage and make sure that when the patient is transferred from the acute medical unit it is to the care of a diabetes team.

Reassurance for patients with DKA

• Your nausea and vomiting will stop as the drips start to work

• You are breathing quickly to blow off the toxic ketones

• Your breathlessness will improve as your diabetes is brought under control

• The nasal tube is to stop your stomach overfilling with air

• Try not to panic on the oxygen mask – you need it to boost your oxygen levels

• Your appetite will return as soon as the diabetes comes under control again

• All the blood tests and close monitoring are needed for the first few hours only

• You can take over blood testing and insulin treatment once you feel well enough

• We are giving you powerful antibiotics to cover any possible infections

• Your heart is fine: the monitor is simply telling us its rate and rhythm

• The blood tests from your wrist are the best way to assess your overall progress

Answering relatives’ questions in DKA

The patient’s relatives will be extremely concerned and frightened by the way in which the diabetes appears to have suddenly become a threat to the patient’s life. They will need to be reassured.

Should we have acted sooner? Examine the relatives’ understanding of diabetes. To what extent are they involved in the patient’s diabetic care? If the DKA has been precipitated by an intercurrent infection, are they aware of the problems of acute illness in the diabetic? What warning signs did they act on to seek help, and were these appropriate?

What else could we have done? Are there areas where they would like more information? The relatives may be frightened by the idea of diabetes, injections, adjusting insulin and so forth. In these circumstances, the diabetes specialist nurse will have an important educational and supportive role, and will need to be involved.

What will happen next? You can reassure the relatives that the vast majority of patients with DKA make a complete recovery. There are, however, complications that can occur and the management will have to be particularly intensive for the first 6h or so. There will be a lot of clinical activity during this time and it is usually helpful to put some constraints on the number of visitors during this period.

Clinical details from the relatives

The relatives may also be an important source of urgent clinical information, particularly if the patient is too unwell or confused to give a full history. The relatives can provide important clinical details of the illness and the usual level of diabetic control. The description of the symptoms and how they progressed will help determine the nature of any precipitating infection. Was there headache and fever to suggest meningitis, dysuria and renal tract pain to suggest urinary sepsis, or diarrhoea and vomiting to suggest gastroenteritis? What evidence do the relatives have concerning the usual level of diabetic control and the degree of cooperation and compliance with treatment? Is there a blood-sugar diary card to look at? What is the usual insulin regimen? When was it last administered and when did the patient last eat or drink? On a general note: is there a history of heavy alcohol intake (which can have an impact on diabetic control) and are there any allergies, particularly to antibiotics?

The importance of patients’ and relatives’ education in diabetes

The patient in Case Study 6.5 is typical of the diabetic patient who is uncertain what to do when he becomes acutely unwell. There were clear warning signs from his osmotic symptoms that his diabetic control was deteriorating. His acute abdominal symptoms were either gastroenteritis or the first indications of DKA. He should have sought urgent help when he first found urinary ketones, or preferably when he had the combination of vomiting and an inability to keep up with his fluids. Before he was discharged from the Acute Medical Unit, the patient and his mother were given a clear explanation of what had happened and what action they could take in future.

Case Study 6.5

A 17-year-old boy with a year’s history of Type I diabetes gave a 2-week history of tiredness, polyuria and high BM stix. He did not seek help or adjust his insulin. Two days before admission to hospital, he developed diarrhoea and continued to vomit all day. He continued his insulin, but was unable to take any fluids. By the evening his urine showed ketones, but he waited a further 12h before asking for help. On admission he was dry and hypotensive.There were large amounts of ketones in his urine.Test results were: blood sugar 28.5mmol/L, creatinine 112μmol/L and urea 8.5mmol/L. pH was 7.29, bicarbonate was low at 12mmol/L. He improved rapidly with i.v. fluids and insulin.

Information for Diabetics: What to do on Days When You Are Sick

• The main problems occur with gastroenteritis and infections

• When you are ill you may need more short-acting insulin than normal

• Your blood sugar can rise even if you cannot eat your normal diet

• While you are ill, check your blood sugar between 2- and 4-hourly. Your target blood sugar should be around 10mmol/L

• Adjust your insulin only if you are confident in doing so. (An example of self-adjustment would be a diabetic who is on a bolus regimen totalling, say, 36 units per day who could increase each bolus by 4 units if the sugar values were between 13 and 22mmol/L)

• If your blood sugar is less than 13mmol/L, continue with your usual insulin doses

• Never stop your insulin

• Keep your carbohydrate intake up with milk and sugar, snacks, ice cream and high-sugar soft drinks

• Also try to drink 4–6 pints (3.6–5.4 litres) of sugar-free liquid per day

• Seek help if you are ill, especially if you are vomiting or if your sugar is continuously > 22mmol/L or if your urine is positive for ketones

• If the breathing becomes rapid, the vomiting persists and there is drowsiness you, the patient, or your relatives, must seek urgent medical attention

Hyperosmolar Non-Ketotic Diabetic Coma (HONK)

This relatively rare complication is seen in elderly Type II diabetic patients and has a 50% mortality rate. The patients present extremely unwell, with very high sugars and impaired consciousness levels, but without ketoacidosis. They are usually profoundly dehydrated due to osmotic fluid loss. The history usually involves a precipitating illness – an infection in 80% of cases – with vomiting and thirst that has often been relieved by high volumes of very sugary drinks. The diagnosis is made from the clinical setting and the finding of a high blood osmolality (over-concentrated blood). The osmolality can be calculated by a simple formula using standard blood results:

The normal osmolality is 275–295mosmol/kg; in HONK, the level is greater than 350mosmol/kg.

Management includes CVP monitoring, nasogastric intubation to prevent aspiration and judicious fluid therapy to replace half of a typical 7-litre deficit in the first 12h, and the remainder over the next 24h (→ p. 228; the importance of fluid balance in nursing the diabetic patient).

Hypoglycaemia

The possibility of hypoglycaemia must always be the first consideration when faced with an acute neurological or behavioural disturbance, whether the patient is diabetic or not. It is a major danger for patients who are on insulin.

Symptoms

The symptoms of hypoglycaemia present acutely and progress rapidly as the blood sugar drops. Mild symptoms of headache, slight mood changes, excessive sweating of the face and hands or subtle changes in behaviour occur as sugars fall to 3mmol/L. As the sugar decreases, adrenaline (epinephrine) is released, which produces the classic warning signs: sweating, irritability, tremor, palpitations and intense hunger. There may be double vision, aggression and poor cooperation. With severe hypoglycaemia, at sugar levels of 1–2mmol/L, there may be epileptic fits, confusion, stroke-like symptoms and coma. Untreated, severe hypoglycaemia can result in irreversible damage. In prolonged hypoglycaemia death may occur, but this is a rare occurrence and tends to be associated with deliberate overdosing of either insulin or oral hypoglycaemics.

Causes

Hypoglycaemia is most common in Type I diabetes as a result of mismatches of insulin, carbohydrate intake and carbohydrate utilisation. Many Type I diabetics now tend to aim for low/normal blood sugars using three- or four-times-daily short-acting insulin. Although these intensive regimens reduce the incidence of long-term complications, they can put the patients at an increased risk from hypoglycaemia. Missed meals, excessive unplanned exercise and (particularly the morning after) an alcoholic binge can all lead to acute hypoglycaemia. Interestingly, islet cell function partially recovers when new diabetics are first started on insulin. This is a temporary effect that lasts only a few months, but the extra natural insulin puts new diabetics at risk from hypoglycaemia during this ‘honeymoon period’.

Prolonged hypoglycaemia can occur in Type II patients if they are taking oral hypoglycaemics. It is a particular problem in the elderly if they are inappropriately given long-acting hypoglycaemics such as glibenclamide or chlorpropamide, if they eat poorly and, particularly, if they abuse alcohol.

Management

Hypoglycaemia is the ultimate medical emergency: the presentation is dramatic, the benefits of treatment are immediate and, most importantly, to miss or to delay treatment is a disaster. Permanent neurological damage from hypoglycaemia, although rare, can be devastating. If you suspect hypoglycaemia, check the BM stix and, if possible, send a laboratory glucose for later confirmation. If the patient is in coma, your priority is to ensure the safety of the patient with regard to his airway, breathing and circulation. If the patient is conscious and cooperative and you diagnose hypoglycaemia, you should give 20g of quick-acting carbohydrate as:

• 100ml Lucozade®

or

• six glucose tablets

or

• four teaspoonfuls of sugar

Intravenous glucose

A large-bore Venflon® will be needed if there is an impaired consciousness level, as i.v. glucose will be needed (→Table 6.5). Give 25g of glucose as 10, 20 or 50% glucose, but remember: the stronger the glucose the more irritant the solution to the veins. Check the BM stix at 5 and 30min after treatment has been given. Hypoglycaemia due to oral hypoglycaemics can be prolonged, as some of the drugs have a long course of action. These patients will need careful monitoring for recurrence and may need a 10% infusion of glucose continued for a number of hours.

| Glucose solution | 25g glucose in: |

|---|---|

| 50% | 50ml |

| 20% | 125ml |

| 10% | 250ml |

Intramuscular glucagon

If you cannot get venous access, then glucagon can be used. Glucagon is a naturally occurring hormone that has the exact opposite effect to insulin. Give 1mg of glucagon intramuscularly. It acts more slowly than glucose (in coma consciousness returns in 10–15min). Glucagon also causes nausea and vomiting and is not very effective in patients who are starved or who have consumed excessive alcohol.

Always seek the cause for hypoglycaemia

Case Study 6.6 illustrates why it is important to find out the cause of the hypoglycaemia. Cortisone, like adrenaline (epinephrine) and glucagon, is a stress hormone that is released in response to hypoglycaemia to try and correct the body’s blood sugar. Addison’s disease, like diabetes, is another autoimmune disease in which the body produces antibodies against the adrenal gland, the source of cortisone. This patient’s natural ability to correct hypoglycaemia was impaired due to his lack of cortisone. Addison’s disease and diabetes share a similar mechanism and are known to occur together, in the same patient. This case illustrates the need to follow up any case of hypoglycaemia to establish the exact reason for its occurrence.

Case Study 6.6

A 35-year-old diabetic was admitted with severe hypoglycaemia. He had been seen by his parents the evening before and had then been found in a confused and barely rousable state in the morning. He had been a diabetic for a year and was quite depressed about its implications for the future. He remained confused and hypoglycaemic for several days, in spite of high-dose i.v. glucose. Initial suspicions that he had taken an insulin overdose could not be substantiated. He was discharged home after eventual recovery, but was admitted a day later with further hypoglycaemia.

Further investigations revealed that he had also developed Addison’s disease. He responded well to cortisone therapy and his hypoglycaemia resolved.

In managing all these diabetic emergencies, it is important to be familiar with the various i.v. infusions (→Table 6.6).