16 Diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidaemia

Diabetes Mellitus

Who classification of diabetes

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Type 2 DM (> 90% of total) results from a progressive fall in insulin secretion with, in addition, resistance to the action of insulin. It is frequently associated with obesity and the ‘metabolic syndrome’ (p. 429). Early in the disease, there may be high levels of circulating insulin, in contrast to type 1 diabetes. Hyperglycaemia results from a progressive failure of the pancreatic β-cells to maintain high levels of insulin secretion to overcome peripheral resistance. The diagnosis is therefore often delayed since endogenous insulin levels are initially sufficient to prevent ketogenesis and a catabolic state. Intercurrent illness, with increased insulin resistance secondary to release of stress response hormones, is associated with worsening glycaemic control and consequent dehydration. The presentation is often with a concurrent illness in an adult with a history of polyuria, polydipsia and malaise over some weeks.

Higher-risk population groups that may benefit from screening for type 2 diabetes include:

Other types of diabetes

Diagnosis

Diagnostic criteria

• Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT)

Management of diabetes

The aims of management are to:

Insulin therapy

Insulin is the only therapy suitable for the treatment of type 1 diabetes and in cases where endogenous insulin production has been significantly reduced, such as haemochromatosis. Interruptions in insulin therapy render these individuals at risk of ketosis. Insulin is also used to cover periods of intercurrent illness in type 2 diabetes when insulin resistance is increased, or there are concerns that hepatic or renal clearance of an oral drug may be impaired. Progressive β-cell failure is seen in type 2 diabetes and thus oral antidiabetic agents may with time fail to control glycaemia adequately. While there is often resistance to injectable therapy, either through patient preference or a fear of weight gain, initiation of insulin in this group of patients should not be delayed.

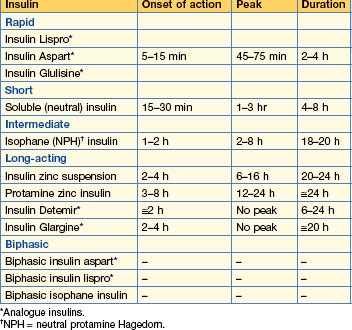

Insulin formulations (Table 16.1)

Principles of insulin treatment

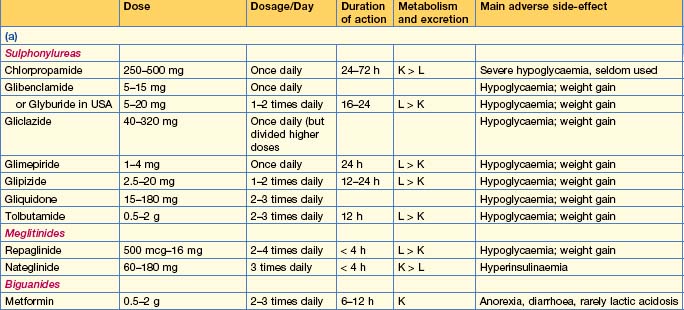

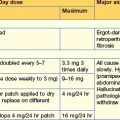

Oral antidiabetic drugs (Table 16.2)

Insulin secretagogues

Insulin sensitizing agents

Intestinal enzyme inhibitors

Other therapies

• Incretins

Practical management of type 1 DM

Monitoring

Pharmacotherapy

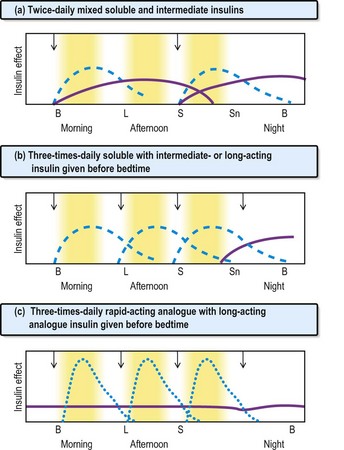

Fig. 16.1 Insulin regimens. Profiles of soluble insulins are shown as dashed lines; intermediate- or long-acting insulin as solid lines (purple); and rapid-acting insulin as dotted lines (blue). The arrows indicate when the injections are given. B, breakfast; L, lunch; S, supper; Sn, snack (bedtime).

Risk factor reduction (Table 16.3)

| Parameter | Ideal | Reasonable |

|---|---|---|

| HbA1c | < 7% | < 8% |

| BP (mmHg) | < 130/80 | < 140/80 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | < 4.0 | < 5.0 |

| LDL | < 2.0 | < 3.0 |

| HDL* | > 1.1 | > 0.8 |

| Triglycerides | < 1.7 | < 2.0 |

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Practical management of type 2 DM

Diet

Monitoring

Indications for hospital admission

Diabetics required to fast for surgery and other procedures

The procedure for insulin-treated patients is simple:

Diabetes and pregnancy

Glycaemic control should be optimized prior to conception to reduce the risk of congenital malformations. Women on oral hypoglycaemic agents should be switched to insulin, although metformin may be continued. Poorly controlled diabetes in pregnancy is associated with stillbirth, pre-eclampsia, fetal macrosomia and hydramnios. Women should be monitored intensively by both the diabetic and the obstetric teams.

Diabetic ketoacidosis

Diagnosis and management

Diagnosis and management are shown in Box 16.1. The patient should be closely monitored until stable.

Box 16.1 Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of diabetic ketoacidosis

Phase 1 management

Box 16.2 Electrolyte changes in diabetic ketoacidosis and the hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state

Examples of blood values

| Severe ketoacidosis | Hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state | |

|---|---|---|

| Na+ (mmol/L) | 140 | 155 |

| K+ (mmol/L) | 5 | 5 |

| Cl– (mmol/L) | 100 | 110 |

| HCO3– (mmol/L) | 5 | 25 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 8 | 15 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 30 | 50 |

| Arterial pH | 7.0 | 7.35 |

and in the example of the hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state:

Hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state

Hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state (HHS) is the hyperglycaemic crisis associated with type 2 diabetes. It is due to a reduction in effective circulating insulin levels, exacerbated by elevated levels of counter-regulatory hormones such as cortisol, growth hormone and catecholamines. Thus hepatic glucose production is increased but there is sufficient insulin to prevent significant ketosis. Mortality rates for HHS are as high as 15%, increasing with age and co-morbidity.

Investigations (see Box 16.2)

Management

Hypoglycaemia

Repeated episodes of hypoglycaemia in a previously well-controlled diabetic should raise the possibility of malabsorption, such as that seen in coeliac disease, a loss of counter-regulatory hormones as in Addison’s disease, or chronic kidney disease with reduced clearance of hypoglycaemic agents, including insulin. Recurrent hypoglycaemia is sometimes treated with insulin pump therapy.

Complications of diabetes

Macrovascular disease

Management of hypertension

Hypertension predisposes to cardiovascular disease and also contributes to the deterioration in diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy. In type 1 diabetes hypertension may result from underlying nephropathy; in type 2 diabetes it occurs as part of the metabolic syndrome with associated dyslipidaemia and central obesity (p. 613).

Nephropathy

Management

Retinopathy

Neuropathy

Other complications

Erectile dysfunction

This is common in diabetes and may be attributed to autonomic neuropathy, although contributory factors, including vascular insufficiency, drugs and other endocrine causes, as well as psychological factors and alcohol, play a role. Treatment is with a phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor, e.g. sildenafil 50 mg. Do not use with nitrate therapy, as severe hypotension can be fatal.

The diabetic foot

Management

Hyperlipidaemia

• Hypercholesterolaemia

Treatment

• Goals of treatment

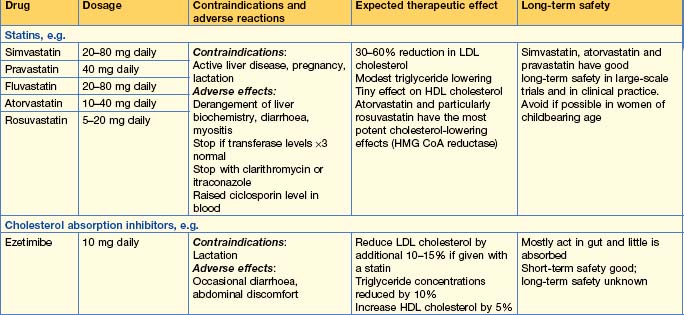

• Therapy (Table 16.4)

American Diabetic Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus — position statement. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Suppl 1)):562-569.

Joint British Diabetes Societies Inpatient Care Group. The management of diabetic ketoacidosis in adults. www.library.nhs.uk/diabetes/, 2010. Available from

2009 The International Expert Committee Report on the Role of the A1C Assay in Diagnosis of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1327-1334.