CHAPTER 5 DIABETES COMPLICATIONS

EYES

RATIONALE

Diabetes has long been associated with eye problems, including retinopathy, cataracts and glaucoma. Individually or collectively, these problems can lead to visual loss. Diabetic retinopathy is a specific vascular complication of diabetes and is the most common cause of newly registered cases of blindness (12%) in those aged 20 to 64 years in the UK (Evans et al 1991). In type 2 diabetics, glaucoma and cataracts are a more frequent cause of visual loss than retinopathy, but the latter is already present at diagnosis in one-fifth of patients (Macleod et al 1994) and its prevalence relates directly to the duration of diabetes.

Among the risk factors associated with the development and progression of diabetic retinal disease in type 2 diabetics are: raised blood pressure (UKPDS 1998c), increased duration of diabetes (Klein et al 1984), and the presence of microalbuminuria (Savage et al 1996).

The St Vincent Declaration of 1989 set a target to reduce new blindness caused by diabetes by one-third or more (Krans et al 1995). Regular accurate screening for diabetic eye disease can improve the prognosis by detecting abnormalities earlier in their natural history. Active management of microangiopathy affecting the retina has been possible since the development of laser photocoagulation. Cataract surgery and other surgical techniques that may benefit patients with diabetic eye disease are now available.

TARGETS

The aims of a screening and management programme for diabetic eye disease should be to:

SCREENING

Programmes

The two preferred methods of screening for diabetic retinopathy that meet the National Clinical Guidelines’ recommendation of a sensitivity of at least 80% and a specificity of at least 95% (Hutchinson et al 2001) are:

The National Screening Committee recommended that a diabetic retinopathy screening programme should:

The preferred screening methods are more likely to meet these criteria.

Fundoscopy

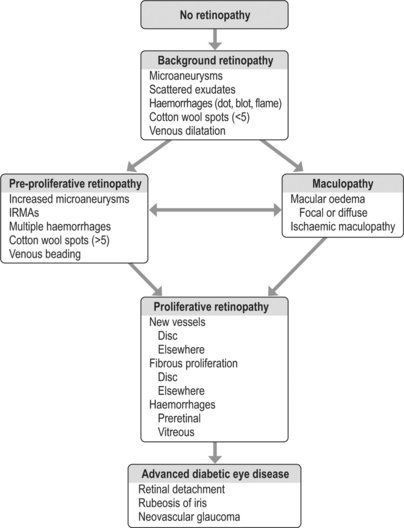

The findings of the examination will determine the classification of diabetic retinopathy, as outlined in Figure 5.1.

INTERVENTIONS

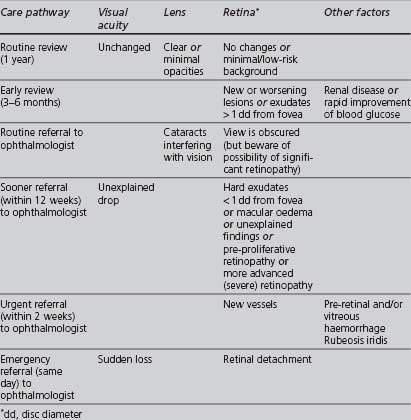

The appropriate management of diabetic retinopathy should follow the pathway outlined in Table 5.1.

TABLE 5.1 Management pathways following eye assessment (NICE 2002a, UK National Screening Committee 2004)

Suitable interventions that can be undertaken in primary care include:

Secondary-care interventions may include the following:

NEPHROPATHY

RATIONALE

Diabetic nephropathy is one of the more serious complications of diabetes. It occurs in 20–40% of patients with diabetes and its prevalence is increasing. Indo-Asian and Afro-Caribbean type 2 diabetics are at a greater risk of developing diabetic nephropathy than whites. In England, the rates for initiating treatment for end-stage renal disease were reported as 4.2 and 3.7 times higher in Afro-Caribbeans and Indo-Asians, respectively, than in whites (Roderick et al 1996).

Persistent albumin excretion greater than 300 mg/day, termed macroalbuminuria, in the absence of infection, marks the onset of diabetic nephropathy, and is also associated with increased mortality, particularly from vascular causes (Macleod et al 1995). The natural history of overt diabetic nephropathy is to progress to end-stage renal failure. The presence of lesser amounts of urinary albumin (less than 300 mg/day), termed microalbuminuria, indicates early renal damage. This is a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in type 2 diabetics (Dinneen & Gerstein 1997). About half of diabetics develop microalbuminuria at some stage. Of these (the study’s subjects were on insulin) 30–50% will progress to macroalbuminuria, but 30–50% will revert to normal albumin excretion and 20–30% will continue to have microalbuminuria (Laing et al 2003). If retinopathy is also present, then diabetes-related renal disease is the likely cause of the albuminuria. If retinopathy is absent, other causes of renal disease should be considered (NICE 2002b).

Prompt and effective interventions, particularly at an early stage, may both prevent end-stage renal failure and reduce the high risk of cardiovascular disease. The management of chronic kidney disease is now the subject of an NSF published in 2005 (DH Renal NSF Team 2006).

SCREENING

Screening for diabetic nephropathy should check at least annually two parameters:

Urinary albumin (including microalbuminuria)

The categorisation of levels of albumin excretion is explained in Table 5.2.

| Category | Spot collection (ng/ml creatinine) |

|---|---|

| Normal | < 30 |

| Microalbuminuria | 30–299 |

| Macro- (clinical) albuminuria | 300 or more |

The “gold standard” for the measurement of urinary albumin excretion is a timed urine sample (either over 24 hours, enabling simultaneous measurement of creatinine clearance, or 4 hours), but this is not a practical screening procedure for widespread use in the community.

Sending an early morning urine sample (also referred to as a “spot check”) to a chemical pathology laboratory to measure the albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR) is both more practical and the preferred method recommended by the ADA. ACR levels equal to or greater than 2.5 mg/mmol in males or 3.5 mg/mmol in females indicate microalbuminuria. The test needs to be repeated for confirmation, as microalbuminuria can be transient. One of the authors completed a study in which the prevalence of microalbuminuria in diabetics in an ethnically mixed UK community was 19.3%. The characteristics independently associated with a higher prevalence of microalbuminuria were current insulin use, current smoking, older age, higher systolic blood pressure and poorer metabolic control, but there was no significant association with either increasing duration or gender. Unfortunately, the sample size was not large enough to determine whether there was an association between microalbuminuria and Indo-Asian ethnicity (Levene et al 2004).

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

The glomerular filtration rate can be calculated using a formula and has been proposed as a more accurate, but logistically feasible, estimation of renal function. The 4-variable Modification of Diet and Renal Disease (MDRD) (Levey et al 1999) formula uses the patient’s creatinine, age (valid only between 18 and 70 years), sex and race:

Pathology laboratories have started reporting eGFR automatically (with white ethnicity as default) using the MDRD formula: the result must be multiplied by 1.21 if the patient is black African. If the laboratory does not provide an eGFR result or if looking at a historical creatinine result, then eGFR can be calculated using a readily available online calculator: http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/gfr_calculator.cfm.

The Renal NSF classifies those with kidney disease into 5 stages, based upon eGFR and the presence of urinary albumin (see Table 5.3).

TABLE 5.3 Classification into CKD stages 1 to 5, based upon estimated glomerular filtration ratio (eGFR)

| Stage | eGFR (ml/min) | Other |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ≥ 90 | Haematuria or proteinuria must be present |

| 2 | 60–89 | Haematuria or proteinuria must be present |

| 3 | 30–59 | |

| 4 | 15–29 | |

| 5 | ≤ 15 or renal replacement therapy |

MANAGEMENT

A number of interventions have been shown to delay the progression of diabetic nephropathy.

Management can be divided into nonpharmacological and pharmacological:

Nonpharmacological

Pharmacological

Lowering blood pressure

Tight blood pressure control is the most important intervention for delaying the development of diabetic nephropathy (UKPDS 1998c). The target is a diastolic blood pressure below 75 mmHg in “normotensive insulin-dependent” or 90 mmHg in “hypertensive non-insulin-dependent” (BNF).

There is strong evidence for the reno-protective effect of ACE inhibitors/ARBs which have a greater effect upon urinary albumin excretion, a stronger marker for renal disease and cardiovascular health, than other blood-pressure-lowering drug classes. A Cochrane review suggests that ACE inhibitors are the best drug class to prevent microalbuminuria and nephropathy (Strippoli et al 2005). One randomised controlled trial (RCT), whose subjects were people with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and microalbuminuria, reported that, compared with placebo, an ARB (irbesartan) reduced progression from early to late nephropathy over 2 years (Parving et al 2001). Another RCT, whose subjects were people with type 2 diabetes and early nephropathy found no significant difference in glomerular filtration rate change, mortality, or cardiovascular disease (CVD) events between an ARB (telmisartan) and an ACE inhibitor (enalapril) over 5 years (Barnett et al 2004). Other studies have found ARBs to be reno-protective in patients with type 2 diabetes and overt nephropathy (Brenner et al 2001, Lewis et al 2001).

However, effective blood pressure control is paramount, and non-DCCBs, β-blockers, or diuretics should be used in combination with or, if ACE inhibitor/ARB is contraindicated or not tolerated, as alternatives to inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (Black et al 2003, Pepine et al 2003).

Improving lipid profile

Prescribing a statin reduces cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetic nephropathy.

The small Danish Steno-2 study compared the effect of a targeted, intensified, multifactorial (both lifestyle and pharmacological) intervention with that of conventional treatment on modifiable risk factors for CVD in type 2 diabetics and microalbuminuria, showing significantly reduced hazard ratios for the development of both macro- and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetics with microalbuminuria (Gaede et al 2003).

FEET

See also the subsection on neuropathy.

RATIONALE

Definition

WHO has defined the diabetic foot as a group of syndromes in which neuropathy, ischaemia and infection lead to tissue breakdown, resulting in morbidity and possible amputation (Krans et al 1995).

Pathological processes

There are two main pathological pathways in diabetic feet:

In diabetics attending dedicated foot clinics, approximately 50% have neuropathic feet and 50% have neuro-ischaemic feet (Edmonds et al 1986).

The burden of diabetic foot problems

A UK population-based study in type 2 patients gave a prevalence of 1.4% for foot ulcers, but the prevalence of the risk factors that give rise to ulcers was 41.6% (Kumar et al 1994). Once a limb has been amputated the prognosis for the contralateral limb is poor (Ebskov & Josephsen 1980). Foot ulcers occur more frequently in whites than in Indo-Asians or Afro-Caribbeans, and are associated with adverse social circumstances such as deprivation and isolation (Boulton 1997), poor glycaemic control, the presence of other vascular risk factors (e.g. smoking) and increased duration of diabetes.

Up to 50% of foot ulcers and amputations could be prevented by patient education and effective intervention (Boulton 1997). Diabetes complications consume considerable resource (both health and social costs). There are no current UK estimates for the costs of treating diabetic foot problems.

AIMS

ASSESSMENT

History

Examination

The four main components of a routine structured foot examination of a person with diabetes are:

More details of each of these examination components are given in Table 5.4.

| Inspect footwear for suitability and for evidence of excessive wear or pressure loading. Inspect distal lower limbs, looking for: |

Ideally, the examination will correctly identify:

Charcot osteoarthropathy

Charcot osteoarthropathy is a progressive condition, associated with neuropathy in diabetics. It is characterised by dislocation of joints, fractures and destruction of the bony architecture. In diabetics, the arch of the foot is most frequently affected. Trauma (even through simple weight bearing) in a severely neuropathic limb is thought to trigger Charcot’s osteoarthropathy. Although not particularly common, it is a major risk factor for foot ulceration and amputation. If suspected, the patient should be referred promptly to the multidisciplinary foot care management team, where the management includes immobilisation of the affected joint and long-term off-loading to prevent ulceration (McIntosh et al 2003).

Categorisation of level of risk

Based upon the information acquired from the history and examination, the level of current risk to the diabetic foot of developing a foot disease or ulcer can be determined. NICE in 2003 has defined the features and management at each level of risk (McIntosh et al 2003). A fifth level (number 5) is added to this categorisation.

The severity of a foot ulcer is classified according to the Wagner system, summarised in Table 5.5 (Wagner 1983).

TABLE 5.5 Wagner classification of foot ulceration (Wagner 1983)

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | High-risk foot; no ulcers |

| 1 | Superficial ulcer (skin deep), not clinically infected |

| 2 | Deeper ulcer, often with cellulitis; no abscess or bony involvement |

| 3 | Deep ulcer with abscess or bony involvement (osteomyelitis) |

| 4 | Localised gangrene (involving toe, forefoot or heel) |

| 5 | Gangrene of the entire foot |

MANAGEMENT

The level of risk to the diabetic foot determines the optimal management pathway, summarised in Table 5.6.

| Level of risk | Management |

|---|---|

| Low risk | Agree management plan, including footcare education |

| Trained patient undertakes own nail care | |

| Arrange recall and annual review as part of ongoing care | |

| Increased risk | Surveillance by podiatrist or practice nurse with increased training |

| Recall and review every 3 to 6 months | |

| High risk | Refer to podiatrist with special interest in diabetes or to local hospital-based specialist diabetes team |

| Recall and review every 1 to 3 months | |

| Active foot disease | Refer urgently to multidisciplinary footcare team (within 24 hours) |

| Emergency foot problem | Admission for in-patient care |

(modified from Mclntosh 2003 foot care guidelines)

Management options in primary care

Health education

This is an essential component and needs to be ongoing, whatever the level of risk. Table 5.7 lists the important health education messages concerning foot care that need to be delivered to diabetics. This can be given by the GP or practice nurse (if suitably trained) or by the podiatrist.

TABLE 5.7 Health education guidelines for foot care in diabetics (Leicestershire Health 1996)

| Hygiene |

|---|

| Good hygiene is essential: |

Optimising glycaemic control

Poor glycaemic control is associated with a greater risk of microvascular complications (UKPDS 1998b).

Antibiotics

Patients with foot infections require prompt and aggressive treatment with one or more broad-spectrum antibiotics. Ideally, the choice of antibiotic should be guided by culture and sensitivity results (where available) and response to treatment. Unfortunately, surface swabs have been shown to be unreliable for determining the nature of infection and the more reliable method of tissue biopsy is not available in primary care (O’Meara et al 2006).

Secondary care interventions

In addition to the above, the following interventions are available in secondary care:

NEUROPATHY

RATIONALE

It is thought that 30–50% of diabetics will develop chronic peripheral neuropathy over their lifetime, with 10–20% having severe symptoms (Tesfaye & Kempler 2005). Diabetic neuropathy is not a single homogeneous condition: its clinical manifestations are diverse. These can be either focal or diffuse, and can cause considerable morbidity and may contribute to premature mortality. The two most frequent presentations are:

SCREENING

The diagnosis of diabetic neuropathy is mainly clinical. More details of the features of the various manifestations of diabetic neuropathy can be found in Table 5.8. Before attributing the neuropathy found to diabetes, nondiabetic causes of neuropathy should be considered, including uraemia, deficiencies (B12), alcohol, neoplasia, paraproteinaemia, Guillain-Barré syndrome and drugs such as nitrofurantoin. Nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea can be caused by infection.

TABLE 5.8 Classification and features of diabetic neuropathies

| Type of neuropathy | Features include |

|---|---|

| Distal symmetric polyneuropathy or peripheral sensorimotor | (Acute or chronic) symmetrical; mainly sensory |

| Pain is sharp, stabbing or burning | |

| Paraesthesia of soles or hyperaesthesia | |

| Often has a stocking-glove distribution | |

| Autonomic: | |

| Orthostasis | Dizziness; drop of > 20 mmHg systolic BP when standing |

| Resting tachycardia | Pulse > 100 beats/min at rest |

| Gustatory sweating | Abnormal facial sweating while eating |

| Gastroparesis | Nausea and vomiting |

| Change in bowel frequency | Diarrhoea (often nocturnal) or constipation |

| Bladder dysfunction | Recurrent UTI, incontinence, palpable bladder |

| Erectile dysfunction (see below also) | Loss of penile erection and/or retrograde ejaculation |

| Mononeuropathy: | Median carpal tunnel syndrome |

| Cranial nerves (III, IV, VI, VII) | |

| External nerve pressure | Radial, ulnar and peroneal nerve palsies associated with pain |

| Proximal motor | Severe pain, associated with poor control |

| Paraesthesiae in the proximal lower limbs | |

| Muscle wasting | |

(modified from Macleod 1997)

MANAGEMENT

The optimal management of diabetic neuropathy depends to some extent upon its type and presentation. Care should be taken to monitor any side effects of any medication used. Some neuropathies, such as cranial nerve mononeuropathy, can improve spontaneously within weeks to months.

The interventions available in primary care include:

Optimising glycaemic control

Maintaining optimal glycaemic control will not reverse neuropathy, but observational studies suggest that it may improve or delay worsening of neuropathy. It is also suggested that avoiding extreme blood glucose fluctuations may be helpful (ADA 2007).

Analgesia

Tricyclic antidepressants have been historically the drugs of choice (e.g. amitriptyline and nortriptyline) for neuropathic pain. A Cochrane systematic review found these drugs to be effective for a variety of neuropathic pains, with best evidence for amitriptyline (Saarto & Wiffen 2005), but tricyclic antidepressants are not currently licensed for the treatment of diabetic neuropathy in either the UK or USA. Proximal motor neuropathic pain may be relieved by amitriptyline. Tricyclics are generally inexpensive, but their use may be limited by their side effects; they may also exacerbate some autonomic symptoms such as gastroparesis. The 5-hydroxytryptamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine has a license for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. There is limited evidence for the effectiveness of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant drugs (SSRIs). Further studies are needed to identify the most effective antidepressant.

Topical capsaicin cream (0.075%) is licensed for painful diabetic neuropathy and may bring some relief, but its use may be limited by the intense burning sensation it can produce when first used. A systematic review found that capsaicin “has poor to moderate efficacy in the treatment of chronic neuropathic … pain. However, it may be useful in people who are unresponsive to, or intolerant of other treatments” (Mason et al 2004).

In intermediate-term studies neuropathic pain has been shown to respond better to opioid analgesics, such as tramadol and oxycodone, than to placebo (Eisenberg et al 2006). These have a role when other treatments have failed, but more research is needed to determine their long-term efficacy and safety.

Treatment of any nondiabetic causes

Appropriate treatment may reduce the symptoms and/or progression of the neuropathy.

Diabetic autonomic neuropathy

The wide variety of agents is used to relieve the symptoms of autonomic neuropathy, which include:

ERECTILE DYSFUNCTION

RATIONALE

There is a greater prevalence of erectile dysfunction in diabetics (AACE 2003), affecting up to 50% of those aged over 50 years, compared to 15–20% in those without diabetes (Marshall & Flyvbjerg 2006). In most cases of erectile dysfunction the causation is believed to be multifactorial. Age is the variable most strongly associated with erectile dysfunction (Feldman et al 1994).

AIM

The aim is to restore or compensate for sexual dysfunction in accordance with the patient’s wishes.

EVALUATION

The causes of failure to achieve and maintain a satisfactory erection can include psychogenic or organic (i.e. vascular, neurogenic or endocrine) “abnormalities”. Apart from diabetes, other potential causes need to be considered (Ralph et al 2000).

History

Lifestyle

Information from the above should provide strong clues as to the origin of the dysfunction. Sudden onset, the presence of some erections, ejaculatory problems and major life events and/or psychological problems suggest a psychogenic cause, whereas gradual onset, no tumescence, the presence of risk factors, a past history of pelvic disease or treatment, certain medication or illicit drug use, smoking and heavy alcohol consumption suggest an organic cause.

Pharmacological options

Phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors

This class of drugs selectively inhibits phosphodiesterase 5, an enzyme that breaks down cyclic guanosine monophosphate (GMP), an intracellular second messenger that produces smooth muscle relaxation and maintains penile blood flow. These drugs have no effect on the libido and do not produce an erection in the absence of sexual stimulation. Although effective and well-tolerated in many, 30 to 35% of patients fail to respond (McMahon et al 2006).

It is important to know their:

VASCULAR EMERGENCIES

MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION

Following an acute myocardial infarction, patients with diabetes should be considered for intensive insulin treatment (currently under evaluation, but with promising results), as well as for the standard therapies of thrombolysis, beta blockers, antiplatelet therapy (aspirin, with the possible addition of clopidogrel) and ACE inhibitors (especially if there is any evidence of left ventricular dysfunction). Although all these therapies have their own side effects, the increased mortality of MI and the further risk of a second event justify a more aggressive approach in patients with diabetes.

CEREBROVAS\CULAR DISEASE

The primary care interventions for prevention of stroke include:

In addition to hypertension and increasing age, atrial fibrillation has been identified by the UKPDS as a major risk factor for stroke in type 2 diabetics (Davies et al 1999). As well as vigorous correction of other risk factors, control of rate (if cardioversion is not possible or successful) and anticoagulation should be considered, with aspirin as an alternative if anticoagulation is either contraindicated or unsuitable. Guidance on the optimal management of atrial fibrillation can be found in the latest edition of the British National Formulary, Section 2.3.1. Seeking a cardiology specialist opinion is often advisable.