Developmental Disorders of the Gallbladder, Extrahepatic Biliary Tract, and Pancreas

Alyssa M. Krasinskas

Introduction

Developmental, congenital, hereditary, and structural disorders that can affect the gallbladder, extrahepatic biliary tract, and pancreas are listed in Box 36.1. This chapter focuses primarily on the few disorders that are encountered peripherally or directly in surgical pathology. Hereditary pancreatitis is discussed in Chapter 39.

Structural Development of the Gallbladder, Extrahepatic Biliary Tract, and Pancreas

Some disorders of the gallbladder, extrahepatic biliary tract, and pancreas are easier to conceptualize if the embryologic development of these structures is understood. The liver, gallbladder, biliary tract, and pancreas bud from the endodermal epithelium of the foregut (i.e., duodenum) at approximately the third week of gestation. A small caudal portion of the liver bud (i.e., caudal foregut diverticulum) expands to form the gallbladder. While the diverticulum enlarges, its connection with the intestine narrows to form the biliary tree. Early in this process, these structures form hollow cylinders that become solid cords because of epithelial cell proliferation. They subsequently develop a lumen by a process known as cellular vacuolization at approximately the seventh week of gestation.

The pancreas arises from the dorsal and ventral diverticula, which first appear at approximately the fourth week of gestation. The dorsal bud elongates to form part of the head, body, and tail of the pancreas. The ventral bud develops at the base of the hepatic diverticulum. The left segment of this structure atrophies, and the right rotates posteriorly with the rotation of the duodenum to fuse with the dorsal bud. Portions of the pancreas derived from either diverticulum are histologically indistinguishable. Because of the direct association of the development of the common bile duct with the ventral portion of the pancreas, they share a common outflow tract, the ampulla of Vater. Although the length of this common channel varies from person to person, it is less than 3 mm in most people, and in some, the two ducts do not converge but drain into the duodenum through two adjacent but separate orifices.1

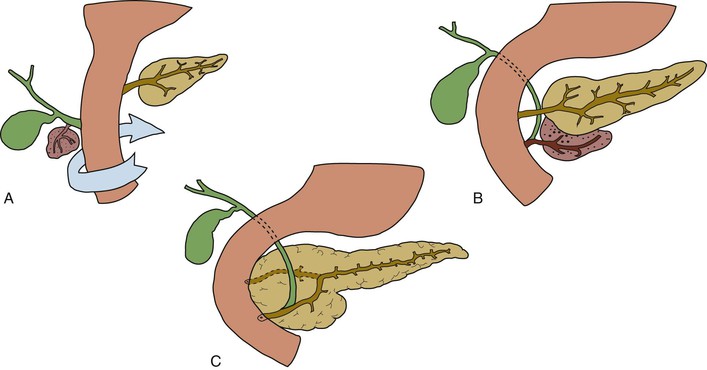

When the two pancreatic buds merge at the sixth to seventh week, their duct systems also coalesce to form the main pancreatic duct of Wirsung. A remnant of the dorsal bud duct persists as the accessory duct of Santorini in approximately 40% of people, with its opening in the minor papilla of the duodenum (Fig. 36.1).1–3

Structural and Developmental Anomalies of the Gallbladder

Congenital abnormalities of the gallbladder are rare. They are traditionally classified according to their number, form, and location.

Agenesis

Gallbladder agenesis was originally described in 1701. It occurs in less than 0.1% of the population. Autopsy series report an equal sex distribution.4 Some patients have a variety of disparate congenital anomalies and syndromes.4–9 Rare familial associations have also been described.10,11 As with many structural anomalies of embryogenesis, the cause of gallbladder agenesis is unknown.12,13 It may result from a complete lack of bud formation or lack of recanalization of the bud during its growth. A compensatory secondary dilation of the right hepatic bile duct that takes on a bile storage function develops in some patients. Patients with gallbladder agenesis who are symptomatic are likely to be women in their fourth or fifth decade who have right upper quadrant symptoms.14 Possible mechanisms responsible for symptoms include abnormalities of the biliary tree, primary duct stones, biliary dyskinesia, and nonbiliary disorders.12

Hypoplasia

Hypoplasia of the gallbladder is classically associated with biliary atresia and cystic fibrosis. Some cases of gallbladder hypoplasia presumably have a cause similar to that of gallbladder agenesis. Gallbladder hypoplasia is associated with rare genetic syndromes and structural anomalies.15,16 This entity likely is underdiagnosed because the main differential diagnosis of gallbladder hypoplasia is fibrotic retraction caused by chronic cholecystitis.

Gallbladder Duplication

Double or triple gallbladders are seldom encountered in clinical practice, although more than 200 cases have been reported. A female predominance is documented among symptomatic patients, whereas an equal sex distribution is seen for asymptomatic individuals.

Multiple gallbladders have been classified according to whether each of the gallbladders has a separate cystic duct insertion into the biliary tree (“H” configuration) (Fig. 36.2) or a common cystic duct insertion (“Y” configuration). This distinction is of vital importance for intraoperative surgical management.17

The spectrum of disease identified in patients with multiple gallbladders is similar to that found in patients with a single gallbladder.17 In the absence of symptoms, prophylactic cholecystectomy is not routinely advocated, although removal of all gallbladders is indicated if only one is found to be pathologic.18

Septation

Septation of the gallbladder (Fig. 36.3) is often diagnosed on preoperative ultrasonography. It most commonly results from cholelithiasis and inflammation, an association that is supported by prominent inflammation and fibrosis in most of the specimens. Congenital gallbladder septation also has been attributed to incomplete cavitation of the developing gallbladder bud.19

Septations may be single or multiple. Rare multiseptate gallbladders occurring as part of a constellation of congenital abnormalities of the hepatobiliary-pancreatic tree offer the best evidence for septation as a congenital event, at least in some patients.20–22 They may occur in the pediatric population and commonly without gallstones. Each septation may contain a mucosal surface with interdigitating muscle fibers. Various amounts of chronic inflammation and secondary cholelithiasis have been described in these specimens.

The term hourglass gallbladder describes a transverse septum that divides the gallbladder into two compartments. This lesion may be congenital or acquired.

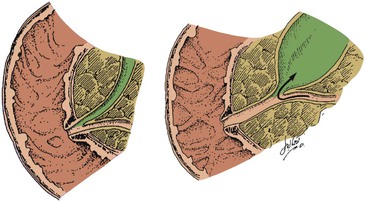

Phrygian Cap

The most exotically named congenital lesion of the gallbladder is the Phrygian cap. It occurs when the fundus of the gallbladder folds over its body. It is a common radiologic finding, occurring in approximately 4% of the general population (Fig. 36.4). The term Phrygian cap refers to the shape of a soft, conical cap worn with the top curled forward by the inhabitants of the Bronze Age country of Phrygia, a region that is now known as Turkey. The lesion is important mainly from a radiologic perspective because it may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of cholelithiasis or pathologic septum.23

Diverticulum

A congenital gallbladder diverticulum is identified in as many as 1% of cholecystectomies. They are distinguished from acquired lesions by mucosa and smooth muscle in the wall of the outpouching. This finding differentiates them from acquired Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses. They may be single or multiple, and they rarely may cause symptoms.24

Anomalous Location

Anatomic variations of position of the gallbladder may occur. Gallbladders occurring outside of the line of the middle hepatic vein on the visceral surface are referred to as aberrant gallbladders. These sites are classified as intrahepatic, left sided (i.e., an isolated finding or associated with situs inversus), transverse, and retrodisplaced.25,26 Rarely, they may be associated with anomalies of the liver.27 A gallbladder with little or no connection to the liver may wander or float in the peritoneal cavity. It may be completely surrounded by peritoneum or have abundant mesentery. Its mobility may allow twisting of the vascular supply and subsequent infarction of the gallbladder.

Heterotopias of the Gallbladder and Biliary Tree

Rarely, heterotopias consisting of pancreas, gastric or intestinal mucosa, liver, adrenal gland, and thyroid tissue have been described in the biliary tree and gallbladder.28 Of these, pancreatic heterotopia in the gallbladder is the most common.29 Most heterotopic lesions are found incidentally at the time of surgery. However, in some patients, classic biliary-type symptoms have been attributed to heterotopia.30

Structural and Developmental Anomalies of the Extrahepatic Biliary Tract

With rare exceptions, anomalies of the extrahepatic biliary tract, apart from choledochal cysts, are usually diagnosed as incidental findings.31 These anomalies are relevant for clinical and radiologic diagnoses and for the prevention of surgical misadventures, such as injury to the extrahepatic biliary system.32

Choledochal Cyst

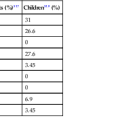

Cystic dilation of the biliary tree was described as early as 1723. Not until the modern era was there significant improvement in understanding the pathophysiology of choledochal cysts. These cysts are uncommon, occurring in approximately 1 of 100,000 to 150,000 live births. Most patients are diagnosed in infancy and childhood; only 20% to 30% of patients are identified as adults.33,34 Table 36.1 summarizes the common presenting features.

Table 36.1

Choledochal Cysts in Adults and Children

| Feature | Pediatric Patients39,48 | Adult Patients49,50,56 |

| Overall occurrence | 75% | 25% |

| Male-to-female ratio | 1 : 4 | 1 : 4 |

| Median age at diagnosis | 2.2 yr48 | 37 yr49 |

| Symptoms | Obstructive jaundice Pain Abdominal mass |

Abdominal pain Cholangitis Jaundice Fever Pancreatitis |

| Differential diagnosis | Infants Biliary atresia Prolonged neonatal jaundice Children Congenital hepatic fibrosis Congenital biliary stricture |

Biliary stones Hepatitis Chronic pancreatitis |

| Most common type | I* | IV* |

Etiology

Choledochal cysts can be caused by a diverse set of abnormalities that predispose to reflux of pancreatic secretions into the common bile duct or obstruction of the distal common bile duct. Its predominance in pediatric populations, gender distribution, greater incidence among Asian populations, and rare association with other anomalies are consistent with a congenital origin.35–37 Most patients have an identifiable anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction between the common bile duct and the duct of Wirsung.38,39

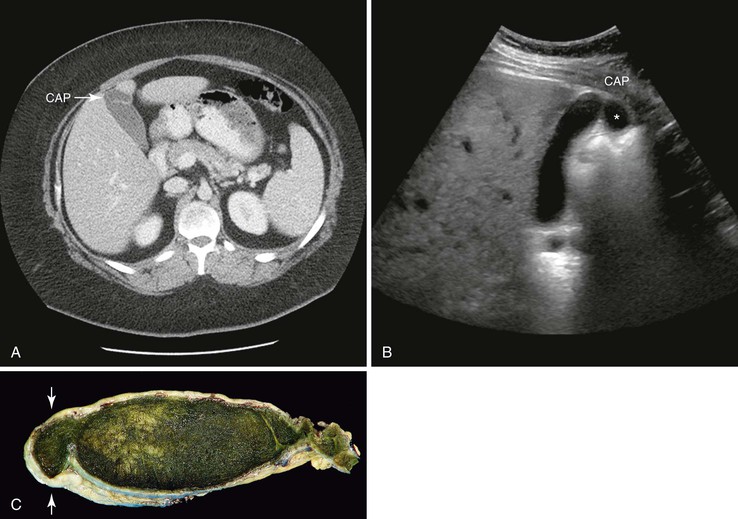

Although the mean length of the common channel increases with age, a common channel more than 6 mm long in adults is considered abnormal (Figs. 36.5 and 36.6).40,41 The formation of this elongated common channel is thought to predispose to pancreaticobiliary reflux, with subsequent in utero dilation of portions of the extrahepatic biliary tract.

Possible mechanisms of distal common bile duct obstruction attributed to choledochal cyst formation include sphincter of Oddi dysfunction,42,43 autonomic innervation abnormalities,44 and other problems of embryogenesis.45 Different pathogenic mechanisms are probably responsible for different types of choledochal cysts. Even in adults, choledochal cysts are thought to be mostly congenital in origin. Uncommonly, adults have a dilated common bile duct after extrahepatic biliary tract surgery with normal results on initial intraoperative cholangiograms. These cases are probably derived in part from secondary stricture formation, although even in these patients, an anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction is common.46

Classification

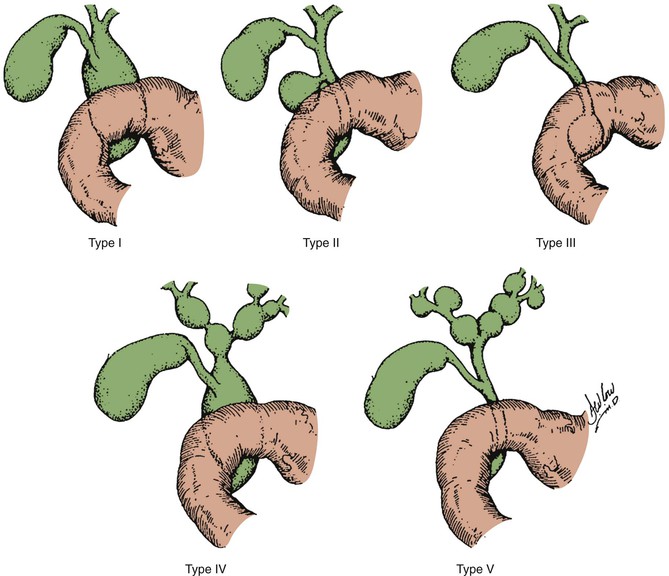

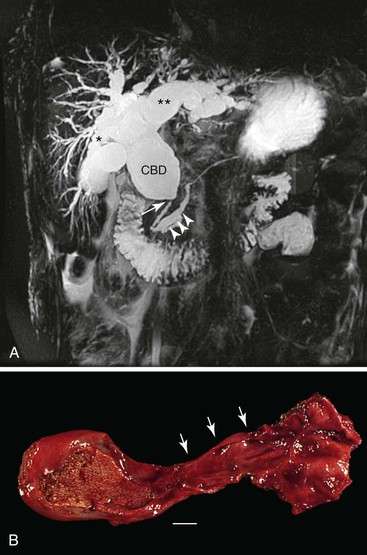

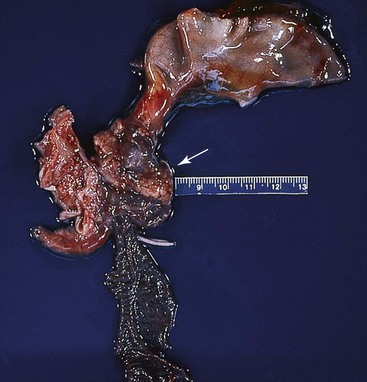

Todani and colleagues47 classified choledochal cysts into five major types according to their anatomic location (Table 36.2 and Fig. 36.7). Ninety-two percent of choledochal cysts in children are classified as type I.48 This cyst has a fusiform or saccular dilation of the common bile duct (Fig. 36.6). Infants commonly have a complete obstruction of the distal common bile duct. Type IV choledochal cysts are the most common type encountered in adults (Fig. 36.8).49 In adults, the distal common bile duct is most commonly patent. Rarely, choledochal cysts may be entirely intraduodenal (i.e., choledochocele) or consist of multiple intrahepatic cysts (i.e., Caroli disease).

Table 36.2

Todani Classification of Choledochal Cysts

| Type | Description |

| I | Fusiform dilation of the extrahepatic duct |

| II | Focal saccular dilation or diverticulum of the extrahepatic duct |

| III | Cystic dilation of the bile duct confined to the duodenal wall (choledochocele) |

| IVa | Combined intrahepatic and extrahepatic dilation of the bile duct |

| IVb | Multiple dilations of the extrahepatic bile duct |

| V | Multiple intrahepatic biliary cysts (Caroli disease) |

Cystic malformations of the gallbladder probably share a common etiologic basis with choledochal cysts. Most patients are diagnosed with a variety of standard and invasive radiologic procedures.49

The Todani classification has been criticized. Visser and colleagues50 made a strong case that the current nomenclature incorrectly groups four distinct diseases together as one entity and that types I and IV are artificially separated. They observed marked dissimilarities between Caroli disease and choledochocele and the remaining lesions classified by Todani as choledochal cysts.50

Pathology

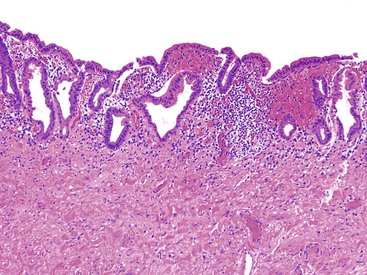

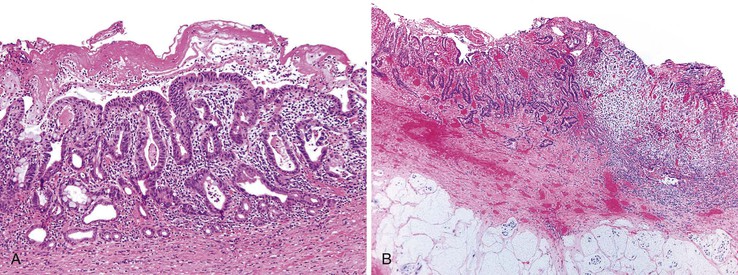

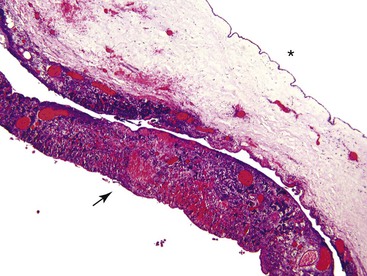

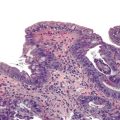

Grossly, a choledochal cyst may contain as much as 2 L of bile. The surface is typically coarsely granular. The wall is normally fibrotic, and distal narrowing is a common feature. Microscopic findings tend to vary with patient age. Intact surface columnar epithelium is characteristic of younger patients, and an increasing degree of chronic inflammation and adhesions to adjacent structures is characteristic of older patients (Fig. 36.9). The cyst wall usually is composed of dense fibrous tissue with various amounts of smooth muscle.37

Complications and Treatment

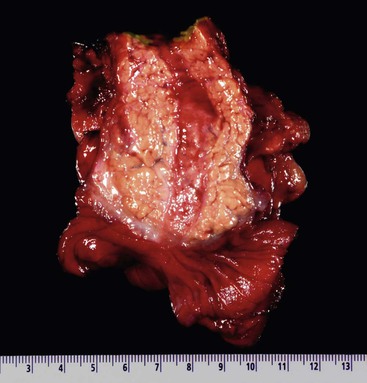

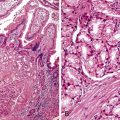

Delayed diagnosis may be associated with untoward complications such as pancreatitis, spontaneous perforation, cholelithiasis, cholangitis, secondary biliary cirrhosis, and portal hypertension. A significant risk of carcinoma is associated with choledochal cysts; this risk increases with age. The risk for children younger than 10 years of age is less than 1%, but the reported risk is as high as 30% to 43% for adults.51,52 Reflux of pancreatic enzymes into the common bile duct and abnormal bile composition may predispose to neoplastic change. For unknown reasons, the neoplasms have a predilection for the posterior wall of the cyst. Most commonly, the tumors are adenocarcinomas (Fig. 36.10),50 although squamous cell carcinomas and anaplastic carcinomas also occur.53,54 Other types of neoplasms are rare.55 These patients also have an increased incidence of gallbladder carcinoma.

Surgical treatment of choledochal cysts involves complete resection when possible, although specific surgical approaches are usually tailored to the findings in a patient.50,56 Resection has been reported to be safe, even in small infants.48 Until recently, Roux-en-Y cystojejunostomy was the surgical treatment of choice. However, long-term follow-up of patients treated in this manner identified a significant lifetime risk of anastomotic stricture formation and development of cholangiocarcinoma. Some published series identified patients previously treated by Roux-en-Y cystojejunostomy who underwent radical excision of their choledochal cysts in an attempt to decrease their risk of cancer. This approach was associated with low long-term morbidity and mortality rates.50,51 Rarely, adenocarcinoma may develop at the site of choledochal site excision. In most cases, the previous surgical excision was found to be incomplete.52

Biliary Atresia

Biliary atresia is the most common neonatal hepatobiliary disorder and is the most frequent indication for liver transplantation in infants. Biliary atresia occurs in 1 of 8000 to 18,000 live births and typically manifests within the first 3 months of life with jaundice, acholic stools, and hepatomegaly in an otherwise apparently healthy infant.57–59 This progressive fibroinflammatory process results in complete obliteration of the lumens of the extrahepatic biliary tree, which leads to intrahepatic cholestatic injury and fibrosis of the intrahepatic bile ducts.

If diagnosed within 60 days of birth, hepatic portoenterostomy can restore bile flow, but 70% to 80% of patients ultimately require liver transplantation because of progressive biliary cirrhosis and its complications.58,59 The term extrahepatic biliary atresia is no longer used because the intrahepatic biliary lesion determines the overall prognosis and outcome of patients affected by this disease.

The two types of biliary atresia are the fetal (syndromic or prenatal) form and the acquired (perinatal) form. The fetal form accounts for as many as 20% of cases of biliary atresia and is associated with other congenital anomalies such as intestinal malrotation; asplenia or polysplenia; portal vein anomalies; situs inversus; congenital heart disease; annular pancreas; Kartagener syndrome; atresia of the duodenum, esophagus, or jejunum; polycystic kidneys; and cleft palate.57,59 This form manifests earlier in infancy with acholic stools and may be caused by a defect in morphogenesis of the biliary tree. Abnormal Notch pathway signaling, including mutations in the Jagged 1 (JAG1) gene and in CFC1, the gene that encodes the cryptic family 1 protein, is thought to play an etiologic role in biliary atresia.60

The more common acquired form of biliary atresia usually manifests with cholestatic jaundice between 1 and 2 months of age and does not have coincident congenital anomalies. Several etiologic factors have been proposed, including infectious, vascular, toxic, and immune factors.57,58

Structural and Developmental Anomalies of the Pancreas

Complete and Partial Pancreatic Agenesis

Complete and partial forms of pancreatic agenesis constitute a rare group of structural anomalies, many of which go undetected because they may not be associated with pancreatic insufficiency. Agenesis of the pancreas is a rare lethal anomaly that sometimes is associated with gallbladder agenesis.61 Partial agenesis, which may be familial in origin, is associated with complete absence of dorsal pancreatic parenchyma and has only rarely been reported.62 Patients may have pancreatitis of the remaining ventral pancreas. A linkage between two families demonstrating pancreatic and cerebellar agenesis and mutations in the PTF1A gene encoding pancreas transcription factor 1A has been described.63

Duct Abnormalities

Because pancreatic development is complex, variations in duct anatomy are relatively common. A detailed autopsy study by Berman and associates,64 in which vinyl acetate casts of postmortem pancreas specimens were used, revealed the previously described pattern of duct arrangement in approximately 90% of specimens. Although several ductal anatomic patterns of development were seen, the most common aberrant finding was insertion of the main pancreatic duct into the common bile duct 5 to 15 mm proximal to the ampulla of Vater. This formation is known as the common channel or the anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction. In endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) series, this variation in duct anatomy has been identified in 0.9% to 28% of patients (depending on patient selection) and is associated with an increase in pancreaticobiliary disease.42,65

Pancreas Divisum

Pancreas divisum is the most common congenital anomaly of the pancreas, occurring in 5% to 10% of the population.66 Variations in the prevalence rate based on ethnicity have been reported.67 Since its identification in the 1970s with the introduction of ERCP, the significance of pancreas divisum has been intensively studied. Pancreas divisum has been identified in 12% to 26% of patients with idiopathic pancreatitis, and the pancreatitis was confined to the dorsal portions of the pancreas in some of these patients.2,68 Conversely, some studies have not shown a significant association between pancreas divisum and increased pancreatic disease.67,69–71

The classic or complete type of pancreas divisum arises from a lack of fusion of the two embryologic portions of pancreas. As a result, the main portion of the pancreas is drained by a patent duct of Santorini into the minor duodenal papilla (Fig. 36.11), and the inferior portion of the pancreatic head drains through the major papilla. An associated stenosis of the minor orifice in a subset of patients with pancreas divisum probably influences the predisposition to pancreatitis. A partial or incomplete type of divisum occurs when a small communication exists between the ventral and dorsal ducts. Several variants of this type have been elucidated.72

Three main clinical manifestations are associated with pancreas divisum: acute relapsing pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, and abdominal pain without evidence of pancreatitis. Inflammation has been attributed mainly to mechanical or obstructive problems in pancreas divisum. Evidence supporting aberrant functioning of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator as a cause of pancreatitis in these patients has been reported.73,74

The role of endoscopic and surgical interventions is controversial. Several excellent synopses of the issues involved have been published.67,71,75

Rare cases of pancreatic neoplasia developing in patients with pancreas divisum have been reported.76–80 At least one single-institution series reported that patients with pancreas divisum have an increased relative risk of pancreatic neoplasia.81

Annular Pancreas

Annular pancreas, which was originally identified at an autopsy in 1818, is a congenital malformation characterized by a ring of pancreatic tissue that encircles the descending portion of the duodenum to various degrees. It is a rare anomaly. A prevalence of approximately 1 in 2000 pancreatic or periduodenal endoscopic ultrasonographic scans was found in one series of adults.82 In their extensive review, Kiernan and colleagues stated that approximately one half of all patients diagnosed with annular pancreas are in the pediatric age group, with most identified in the neonatal period. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract obstruction is the most common initial finding.83 Peptic ulceration, pancreatitis, and more nonspecific symptoms tend to occur in adults.84

The embryologic sequence that leads to annular pancreas is unclear, and several theories have been proposed. One early theory posited that ventral and dorsal segment hypertrophy encircled the duodenum. Hypertrophy of the dorsal segment repositions the main duct anteriorly. Fixation of the tip of the ventral bud before rotation of the duodenum with subsequent persistence of the ventral lobe after rotation is plausible for most cases. However, it is likely that annular pancreas has a diverse set of causes related to anomalies of the ventral and dorsal pancreatic buds and the duodenum.85

Most commonly, the lesion is composed of a flat band of pancreatic tissue circumferentially surrounding the second part of the duodenum (Fig. 36.12). Histologically, pancreatic parenchyma is characteristically found intertwined with the muscularis mucosae. Only rarely is the anterior wall of the duodenum spared. The ductal system most commonly drains around the right side of the duodenum in an anterior to posterior direction, and it merges with the left duct. However, the right duct may pass anteriorly, or there may be multiple small ducts that penetrate the wall of the duodenum and empty directly into the duodenum. Concomitant duodenal atresia or stenosis is often found.2

Annular pancreas is often associated with other anomalies, such as duodenal bands, intestinal malrotation, Meckel diverticulum, imperforate anus, cryptorchidism, and heart and spinal cord defects. Down syndrome has been identified in as many as 20% of these patients. A familial predisposition has also been documented.86,87

Heterotopic Pancreas

Pancreatic tissue that lacks anatomic or vascular continuity with the main body of the pancreas has been identified in 1% to 15% of autopsies.2 Most cases of heterotopic pancreas occur in the upper portions of the GI tract, especially in the prepyloric region of the stomach along the greater curvature, although other intraabdominal sites, including Meckel diverticulum, liver, gallbladder, small intestine, appendix, colon, omentum, and spleen, have been identified. Rarely, pancreatic tissue may arise in extraabdominal sites such as the lung and umbilicus.

Congenital Cyst of the Pancreas

Most cysts of the pancreas, even in the pediatric age group, are pancreatic pseudocysts that form due to pancreatitis. Fewer than 30 cases of true congenital cysts have been reported in the literature.88

Congenital cysts may be solitary or multiple. Solitary cysts have been identified in all age groups, from fetuses to adults, and there is a predominance among female patients. These cysts are thought to arise by developmental errors of pancreatic ducts presumably related to localized obstruction of the duct in utero. Various sizes of cysts in the region of dominant cysts have been cited as further evidence to support this theory of pathogenesis.89 Pancreatic cysts rarely have been associated with polyhydramnios.

Symptoms of congenital pancreatic cysts occur usually in patients younger than 2 years of age. Newborns may have an abdominal mass or an upper GI or biliary obstruction. These true cysts are localized in the tail or neck of the pancreas in 62% of cases. Associations with other anomalies, including renal tubular ectasia, polydactyly, anorectal malformations, and thoracic dystrophy, have been described. Multicystic lesions of the pancreas are usually associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease90 or, rarely, with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

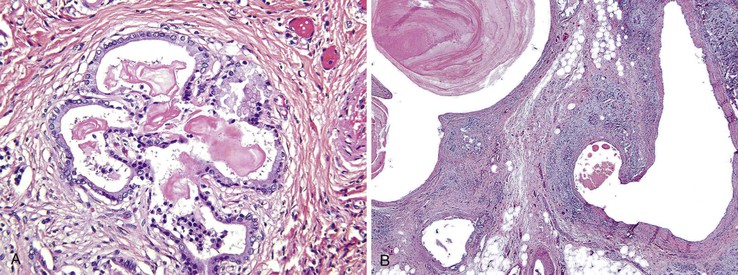

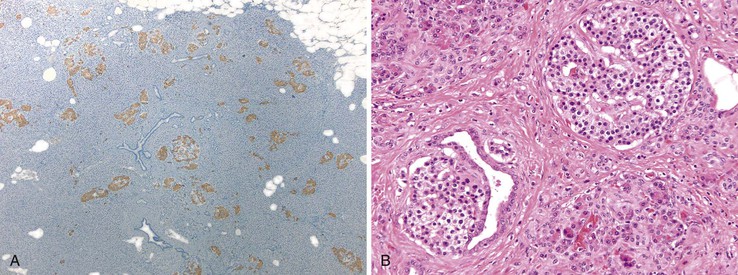

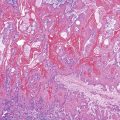

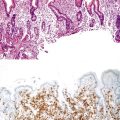

Solitary pancreatic cysts are usually small (1 to 2 cm). Multiple cysts such as those seen in von Hippel-Lindau disease may diffusely efface the pancreas, although the spectrum of changes in these patients is broad. The cysts are lined by non–mucin-producing cuboidal, columnar, or flattened (atrophic) cells with an adjacent fibrous wall (Figs. 36.13 and 36.14).91,92 These lesions should not be confused with intrapancreatic enteric cysts, which most commonly contain gastric mucosa in the cyst wall, although they may rarely contain small intestinal, ciliated, or respiratory-type epithelium.93

Cystic Fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a multisystem disease with many GI tract manifestations. The pancreas was the first organ to be identified as significantly affected in this disease,94 and its name is derived from the characteristic pathologic findings of cysts and fibrosis in the pancreas.

CF, an autosomal recessive disease, is the most common hereditary disorder among whites, affecting 1 of 2000 in this population. CF also occurs in Hispanics, African Americans, and some Native Americans, but it is rare in people of Asian and Middle Eastern origin.

The genetic abnormality associated with CF is located on chromosome 7q31.95 This region is responsible for expression of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein, which functions as a chloride ion channel in epithelial cells. Defective chloride transport, which is associated with decreased bicarbonate secretion, causes mucus, sweat, and digestive juice secretions to become thick and tenacious. In the pancreas, precipitation of acinar secretions into pancreatic ducts leads to obstruction and chronic pancreatitis.96

Many of the clinical and histopathologic findings in patients with CF result from obstruction of exocrine ducts. The hallmark clinical features of CF include pancreatic insufficiency (manifested as steatorrhea), pulmonary disease, elevated levels of sweat electrolytes (i.e., sodium and chloride), meconium ileus, and failure to thrive. Pathologic abnormalities of the pancreas can be recognized as early as 32 to 38 weeks’ gestation, and they progressively worsen with age. Malabsorption resulting from pancreatic insufficiency occurs in early infancy in 85% of patients with CF. Pancreatic insufficiency develops in most of the remaining patients at some stage during the course of their illness. Newborns with CF have a higher connective tissue–to–acinar gland ratio, with more prominent acinar and ductal lumens.

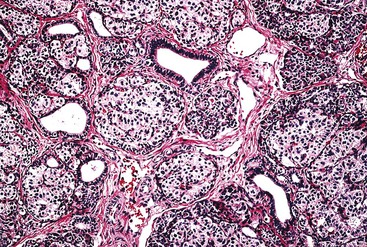

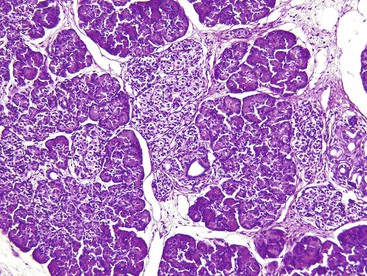

Grossly, the pancreas is often small, hard, and nodular. The parenchyma has a granular appearance due to extensive fibrosis, and cystic spaces are often apparent (Fig. 36.15). The earliest histologic finding is that of abundant eosinophilic concretions, which may be laminated or calcified, within ectatic pancreatic ducts (Fig. 36.16, A). The secretions represent mucoprotein and react with stains for acid mucopolysaccharides. Desquamated epithelial cells and inflammatory cells are usually admixed with the intraluminal secretions. Secondary changes of obstruction include flattening, atrophy, and dilation of acinar and ductal epithelia. Duct dilation with eventual cyst formation and parenchymal fibrosis occurs at an early age in most patients (Fig. 36.16, B). An inflammatory cell infiltrate, including polymorphonuclear leukocytes and abundant lymphocytes, may be seen in the intralobular fibrous tissue within and surrounding the ducts and acini. Intraductal papillary hyperplasia and goblet cell metaplasia may also be evident.

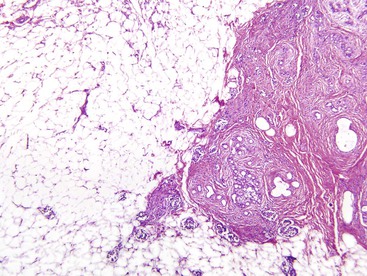

Continued involution of acinar tissue occurs during childhood, initially with a proliferation of fibroblasts, but subsequently by fatty replacement of the entire pancreas (Fig. 36.17). By the end of the first decade of life, the pancreas is replaced by fat, even though the normal gross architecture of the organ is usually well maintained.97 Islets of Langerhans are usually well preserved initially, but as parenchymal damage progresses, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus develops in approximately 25% of patients with CF (mostly adults), caused by an overall decrease in the number of insulin-producing islet cells.98 Sporadic cases of adenocarcinoma of the pancreas arising in patients with CF have been reported, raising concern about a possible association between these two entities.99

In some patients with CF, common bile duct stenosis occurs as a direct result of pancreatic fibrosis affecting the intrapancreatic bile duct. This can occur even in patients with CF without pancreatic insufficiency.100 Sclerosing cholangitis, common bile duct strictures, and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (rare) have been reported.101 Increased fecal bile acid loss caused by malabsorption renders the bile lithogenic. At least one third of older patients with CF have cholelithiasis. Microgallbladders (i.e., gallbladder hypoplasia), mucinous metaplasia, and cystic duct stenosis have been described.100

Congenital Pancreatic Exocrine Deficiencies

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (i.e., Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome), originally described in 1964, is a rare, autosomal recessive, multisystem disorder linked to the SBDS gene on chromosome 7.102 Infants usually have low birth weight and commonly fail to thrive. They often have feeding problems, diarrhea, and hypotonia. Virtually all patients are symptomatic by 4 months of age, and most have pancreatic insufficiency. After CF, this syndrome accounts for the most cases of primary pancreatic insufficiency in childhood.

The characteristic finding in the pancreas is diffuse fatty replacement of pancreatic parenchyma early in the disease course. The high mortality rate results from a constellation of problems involving bone marrow abnormalities (including aplasia with a high risk of leukemia), recurrent bacterial infections, myocardial inflammation, and multisystem anomalies.103–106 Other rare causes of pancreatic exocrine deficiency include Johanson-Blizzard syndrome,107 exocrine pancreatic dysfunction with refractory sideroblastic anemia, and isolated enzyme deficiencies.108

Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes mellitus is characterized by high blood glucose levels that result from defects in the body’s ability to produce and use insulin. Symptoms include frequent urination, lethargy, excessive thirst, dehydration, and hunger.

Diabetes mellitus is separated into two types. Type 1, previously known as juvenile diabetes, is usually diagnosed in children and young adults and develops because the body does not produce insulin. Patients with type 1 diabetes are dependent on insulin therapy. Only 5% of diabetics have type 1 disease. Type 1 diabetes is associated with a genetic predisposition and autoimmunity, which leads to a severe loss of islet beta cells. Other possible causes include viral infection and the toxic effects of drugs or chemicals.

In type 2 diabetes, the most common form, the body does not produce enough insulin or the body’s cells ignore the insulin that is produced. Type 2 diabetes occurs mainly in adults, is usually treated by diet and hypoglycemic medication, and is associated with obesity and a family history of diabetes. Type 2 diabetes is more common among African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders.

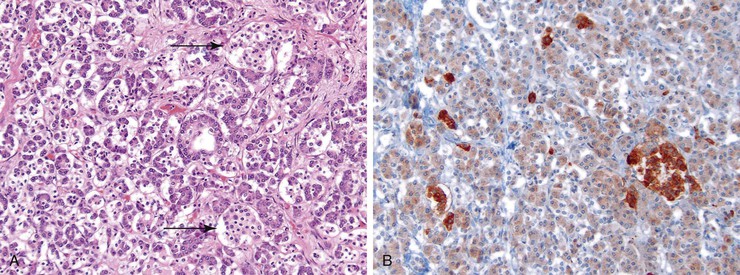

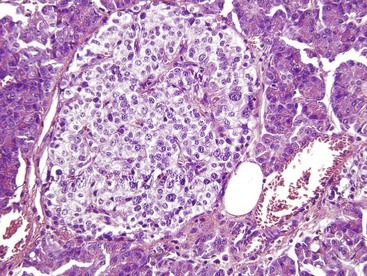

Diabetes is associated with few gross alterations in the pancreas. Microscopically, in type 1 diabetes, the islets often show distinctive changes, even in cases of recent onset. The islets may be small and inconspicuous by hematoxylin and eosin staining (Fig. 36.18). Although some islets in some lobules may appear normal, islets in other lobules may be composed of small, irregular nests of cells with or without fibrosis (i.e., islet fibrosis) and may show continuity between the endocrine and acinar cells (i.e., neotransformation).109

An inflammatory cell infiltrate is often seen in some islets, a finding called insulitis.110 The infiltrate consists predominantly of CD8+ T cells but may also contain CD4+ T cells, B lymphocytes, and macrophages.111 Insulitis tends to occur in young (≤14 years) type 1 diabetic patients with a short (≤1 month) duration of the disease; it is infrequently encountered in older patients and patients with a disease duration longer than 1 year.110 Insulitis preferentially affects islets, which contain beta cells, and after the beta cells have been destroyed, the inflammation subsides.112 Immunohistochemical evaluation can reveal the loss of beta cells, but this may not be a uniform finding.

Islet amyloidosis is a rare feature of type 1 diabetes. Alterations in the exocrine pancreas include acinar cell atrophy and interacinar and interlobular fibrosis. Vascular changes include atherosclerosis of the large arteries and diabetic microangiopathy of smaller arterioles.

In type 2 diabetes, the islets are essentially normal in appearance, and in some patients there are few or no morphologic differences compared with the islets in nondiabetic patients. However, some patients show as much as a 50% reduction in islet cell mass because of a decrease in the total number of insulin-producing beta cells. Islet amyloidosis (Fig. 36.19) is a characteristic histopathologic feature of type 2 diabetes and affects islets containing insulin-producing beta cells, although it is not specific for type 2 diabetes. Both in vitro and in vivo studies have reported that amyloid formation causes the death of islet beta cells.113

Additional alterations in type 2 diabetes include islet fibrosis and fatty infiltration of the pancreas. Insulitis is a rare feature in type 2 diabetes.

Neonatal Islet Cell Hypertrophy and Hyperplasia

Marked variation in the size and number of islets of Langerhans in neonates and young adults has been well documented. The causes are listed in Box 36.2. An assessment of the significance of islet size and number can be made only in conjunction with knowledge of the gestational age at birth.114 The most common cause of islet hypertrophy is maternal diabetes. In addition to hypertrophy and hyperplasia, the islets in infants of diabetic mothers may show increased islet cell volume, pleomorphic nuclei of beta cells, fibrosis, and eosinophilic infiltrates with or without Charcot-Leyden crystals (Fig. 36.20). Alpha cell and pancreatic polypeptide (PP) cell hyperplasia may occur concomitantly with the marked hyperplasia of beta cells.115–117

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome is a congenital, generalized, somatic overgrowth syndrome with various phenotypes, including prenatal and postnatal overgrowth, macroglossia, and anterior abdominal wall defects, most commonly exomphalos. It is usually a sporadic disorder, with only 10% to 15% of cases having a familial origin. It results from dysregulation of imprinted genes on chromosome 11p15.5.118

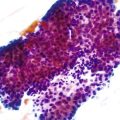

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome is associated with hypoglycemia caused by islet cell hyperplasia and hyperinsulinism in 50% of cases. Islets are enlarged, and smaller clusters of endocrine cells occur in the form of nodular aggregates (Fig. 36.21). Immunohistochemical staining reveals a marked increase in beta cells and a slight increase in alpha cells. The number of PP cells is decreased. Rarely, pancreatoblastoma and cystic dysplasia of the pancreas may be identified in these patients.119,120 They have an increased incidence of nonpancreatic cancers, especially Wilms tumor.

Persistent Hyperinsulinemic Hypoglycemia of Infancy

Persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy (PHHI) is the most common cause of severe, prolonged neonatal hypoglycemia, occurring in 1 of 27,000 to 50,000 births.121 Although an excellent argument for the designation PHHI has been made, the term nesidioblastosis is more commonly used.

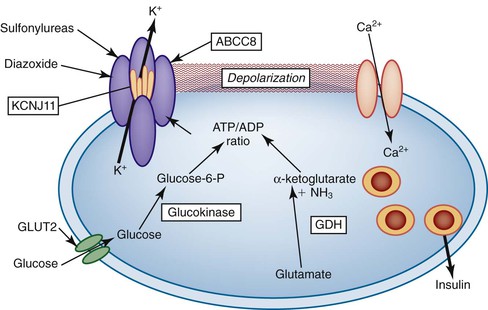

PHHI is caused by mutations in genes that regulate insulin secretion, most commonly autosomal recessive mutations in the sulfonylurea receptor gene, SUR1 (official symbol, ABCC8). Other causes include mutations of the ABCC8-associated inward rectifier gene, Kir6.2 (now called KCNJ11). The ABCC8 and KCNJ11 proteins are the main constituents of an adenosine triphosphate–sensitive potassium channel. Autosomal dominant mutations of glucokinase and glutamate dehydrogenase are uncommonly associated with PHHI (Fig. 36.22).121 Rarely, other causes of congenital hyperinsulinism have been described.122

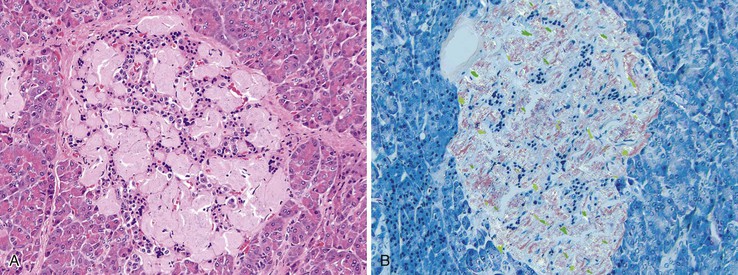

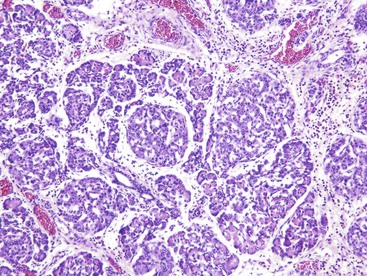

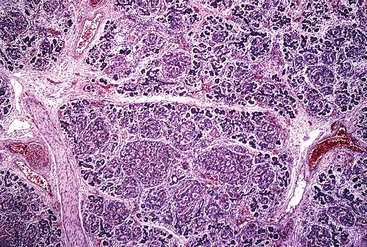

The disease is characterized by diffuse or focal abnormalities of the islets of Langerhans. Histologic features associated with PHHI include islets that are irregular in size and shape (Fig. 36.23), enlargement of beta cell nuclei (i.e., three to four times the size of normal endocrine nuclei) (Fig. 36.24), ductulo-insular complexes (i.e., budding of endocrine cells from duct epithelium) (Fig. 36.25), centroacinar cell proliferation (i.e., ductal cells with pale cytoplasm in centroacinar regions), septal islets (i.e., islets within fibrous septa), and nesidiodysplasia, a subtle increase in endocrine cell aggregates randomly distributed in pancreatic lobules. Adenomatosis, which is excess islet cell proliferation defined as more than 40% of a low-power microscopic field, is found less commonly than diffuse islet cell changes.114,116,123,124 Diffuse hyperinsulinism, which is characterized by enlarged islet cell nuclei throughout the pancreas, most commonly results from recessive mutations in ABCC8 and KCNJ11. Focal-type congenital hyperinsulinism develops in patients with a germline mutation in the paternal allele of ABCC8 or KCNJ11.121,125

Extensive pancreatic resection is often required to control hypoglycemia. Conflicting data have emerged concerning the likelihood of diffuse pancreatic islet cell abnormalities in the setting of adenomatosis on a small sample of intraoperative frozen pancreas section obtained before pancreatic resection. One study of 20 infants found that multiple frozen sections obtained from different parts of the gland allow an accurate intraoperative diagnosis of focal or diffuse PHHI.126 These findings are at variance with other published series.114,124

Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia with severe neuroglycopenia has been identified as a late complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.127,128 The escalating epidemic of obesity has resulted in increasing numbers people who have had bariatric surgery and the emergence of this acquired form of hypoglycemia. Histopathologically, similar to PHHI, diffuse islet hyperplasia and expansion of the beta cell mass (i.e., nesidioblastosis) is seen in the resected pancreata (Fig. 36.26).127,128

Acknowledgment

I gratefully acknowledge Dr. Joseph Willis for providing the previous edition of this chapter as a solid foundation for this revision.