Chapter 9 Developmental Assessment

What Are the Major Areas of Development?

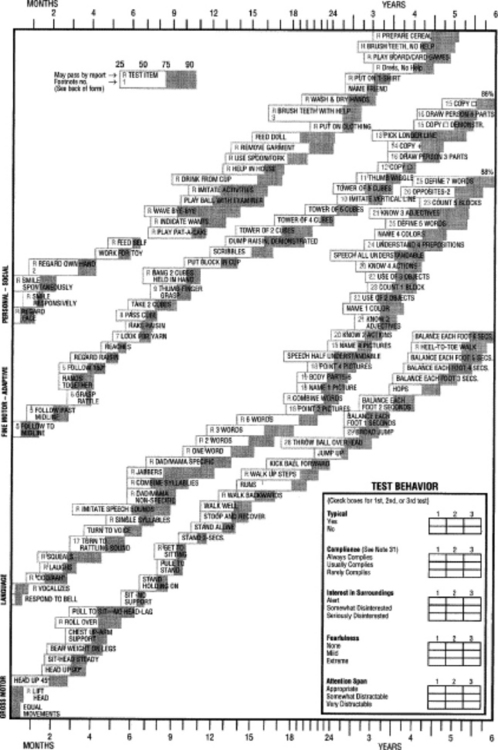

Development is usually divided into broad categories: motor, language, cognition, problem solving, and psychosocial. These categories facilitate ongoing surveillance. Each links to the others and is influenced by progress in the others. An individual’s overall development represents the totality of the interaction. A practical approach to categorizing development can be found in the Denver II, which provides population-based norms for development in four “streams”: gross motor, fine motor/adaptive, language, and personal/social (Figure 9-1). A separate stream devoted to cognition does not appear in the Denver II, but the fine motor/adaptive, language, and personal/social streams all reflect cognitive development. Other, more formal developmental assessment tools use more complex categorization schemes, but for your purposes during the clerkship, simple schemes suffice. The Bright Futures Pocket Guide provides useful lists of age-related developmental skills for day-to-day clinical evaluations.

How Do I Explain Development to a Parent?

First, you must know what “normal development” means and must understand how the child’s developmental variations fit within the expected progress for an individual at a given age. You must examine the child to assess development, looking especially for those delays that signal concerns. If no problems are identified, a plan for ongoing surveillance of development will generally reassure the family and reinforce the appropriateness of the child’s pattern. If, on the other hand, you encounter a child who has not achieved expected milestones or whose pattern deviates enough from the expected course to raise concerns, you must be able to compare the child’s actual abilities with expected development. Your carefully developed observational skills will help identify the problem and also reduce the likelihood that you might overlook something. Attention to communication of “bad news” will assist you to explain concerns to parents and help them understand the need for further assessment and possible referral to a developmental specialist (see Chapter 27).

What Do I Need to Know about Development at Different Ages?

Table 9-1 lists developmental milestones from birth through adolescence.

| Age | Milestone |

|---|---|

| Newborn | Symmetry of movement and muscle tone. Flexed posture. Primitive reflexes (Moro, suck, grasp, root, etc.). Vigorous cry. Focuses on human face. Responds to voice. |

| Birth–6 months | Social smile by 2 months. Gradual disappearance of primitive reflexes and appearance of voluntary, symmetrical motor skills. Reaches for, holds, and then transfers object by 5–6 months. Rolling, sitting, and crawling between 4 and 6 months. Increase in social responsiveness. Vocalization with laughing, babbling and progressively complex sound production. |

| 6–12 months | Progression of motor skills from sitting, to standing with support, to standing unsupported, to “cruising.” Independent walking may not appear until later. Pincer grasp used to pick up objects by 9–10 months. Responds to name, uses single words, plays interactive games, hunts for a hidden object, feeds self with fingers. Stranger anxiety develops. |

| 1–2 years | Walks well by 15 months and walks backward by 18 months. Language progresses from 2–4 words at age 1 year to more complex language with words and short phrases at age 2—but only ∼50% understood by a stranger. Follows directions by ∼18 months. Imitates words and behaviors. Drinks from a cup at 1 year and uses a spoon by 18 months. Stranger anxiety peaks. |

| 2–4 years | Climbs stairs by 2 years, hops on both feet at age 3 years, hops on one foot at 4 years. Language increasingly complex: ∼75% understandable at 3 years, essentially 100% at age 4. Knows name, age, sex. Sings. |

| School age | Learns address, phone number, letters, and numbers. Follows rules by 5 years. Progress in classroom activities provides good screen of development. Increasing independence in activities of daily living (dressing, eating, play, etc.). |

| Adolescence | Social, emotional, and personal interactions increasingly complex. Rapid changes in physical appearance and personality. School provides important clues. Increasing attention to peers and influences outside of the family. Sexuality. Habits including use of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs may develop. |

Case 9-1 Parents of a 4-year-old boy who has recently been adopted from Eastern Europe are concerned that he is not developing appropriately. His past medical history has limited information about his birth. He was placed in an orphanage shortly after birth and, according to records, had “normal” developmental progress. Since arriving in the United States, he has shown many behavioral problems and uses very little language.

Coplan J. The Early Language Milestone Scale, ed 2. Austin, TX: PRO-ED, 1993. (ELM Scale 2)

Frankenburg WK, et al. The Denver II: A major revision and restandardization of the Denver Developmental Screening Test. Pediatrics. 1992;89:91-97.

ed 2. Green M, editor. Bright futures: guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents pocket guide. Arlington, VA: National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health. 2000. 2000. See www.brightfutures.org to download a PDF file of the Bright Futures Pocket Guide

Chung RW. Development and behavior. In: Robertson J, Shilkofski N, editors. The Harriet Lane handbook. ed 17. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2005:231-252.