chapter 6 Developmental and Behavioral Assessment

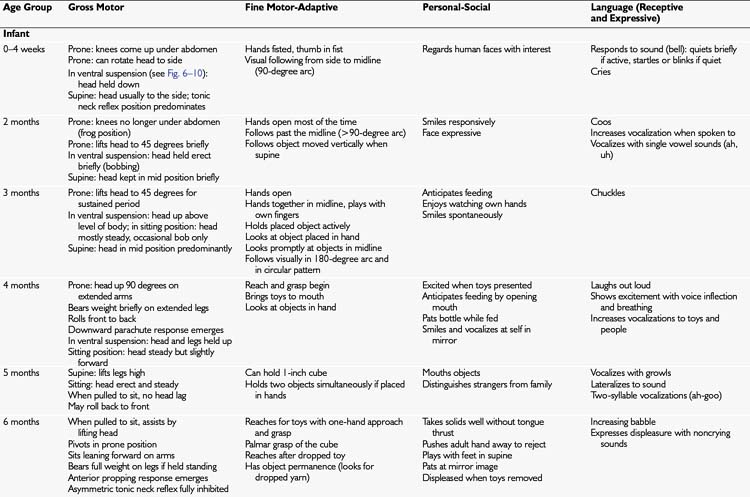

Developmental Surveillance and the Developmental/Behavioral History

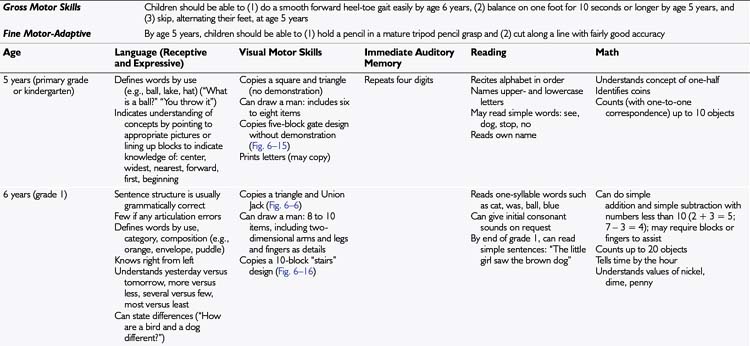

I strongly recommend using a surveillance tool but recognize that there also are times when you will need to ask about development in a more informal way. For preschool children, ask one or two surveillance questions in each key area of development: gross motor, fine motor–adaptive, personal-social, and receptive and expressive language. The milestones indicated in Tables 6–1 and 6–2 provide some suggestions. If you are pressed for time, focus on high-yield areas: for preschoolers, ask about language function and personal-social skills, and for school-aged children, ask about reading and math skills. Remember, you generally will have an opportunity to observe the child’s gross motor and fine motor skills during the physical examination.

Family History

When children have developmental problems, it is important to ask specifically about consanguinity.

Behavior Problems

Children with an autistic behavior pattern show impairment in the following three key areas:

Direct Developmental Examination

Strategies to enhance the child’s participation

Shy and Frightened Children

You know you are in trouble when you walk into the room, introduce yourself, and the youngster immediately dives for his mother and buries his face in her lap. When this happens, you may have the urge to take refuge yourself and refuse to participate—but all is not lost. Most shy children can be won over with a gentle, nonthreatening approach. First, remove any items that the child may consider threatening, including your white coat. Medical equipment should not be hanging around your neck or protruding from your pockets (Fig. 6–1). For children in the hospital, a change of environment may help; a parent counseling room or conference room often offers a less threatening environment.

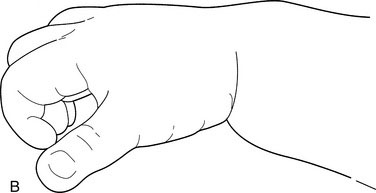

When a child is shy or anxious, do not stare at the child or rush to coax him or her into playing. Sit, chat with the parents, take some of the history, and give the child a chance to get used to you. Offering the child some toys while you speak with the parent may help (Fig. 6–2). Items in the developmental assessment kit come in handy here. For children older than 3 years, paper and crayons work well. You can give almost anything to a younger child, provided it is neither sharp nor ingestible. Blocks, a rattle, or even a penlight will do. Many physicians carry around at least one pocket-sized toy to hand to children. These toys presumably will be retrieved at the end of the visit—an excellent test of your negotiating skills.

Equipment

Besides the usual medical paraphernalia, you need specific materials for the developmental examination. If you are using an informal approach, you need a copy of the appropriate tables of age-appropriate milestones on which to base both questions and assessment. These items are essential. It is not necessary to memorize endless lists of milestones; rather, keep handy copies of Tables 6–1 and 6–2 in this chapter. I also recommend keeping a list of the milestones for primitive reflexes and protective responses of infants, because these milestones are difficult to memorize.

Additional materials

To use the techniques recommended here, you also need the following items:

Start with the infant or child in a sitting position. Babies can sit on a parent’s lap or in an infant seat that provides good support and allows both arms to be free. If a child is in the parent’s lap or in a seat without a tray, improvise a table by having an assistant hold a large book in front of the baby. A highchair or other appropriate-sized chair and table can provide a good surface (Fig. 6–10). Children with problems of muscle tone or motor control may be best assessed while they sit in customized seats or wheelchairs.

Direct assessment of fine motor skills and problem-solving with tasks, such as block manipulation and coloring, is generally very engaging for children. Leave language assessment, particularly parts that require a child to speak to you, until later so that the child is cooperating well before these assessments are attempted. Leave observation of gross motor skills to the very end, because those activities may get the child excited. Gross motor activities also blend naturally into the neurologic and general physical examination (see Chapter 13). Be flexible; a fidgety child may benefit from taking a break in the hallway to play ball or skip.

Looking at Development During The Physical Examination

In infants, primitive reflexes (Fig. 6–11), protective responses, and behavior in the prone and supine positions should be assessed after the physical examination, because the methods used to elicit them may distress the infant.

Developmental milestones

Tables 6–1 and 6–2 list developmental milestones and skills. Although these lists do not replace more detailed developmental assessment, they do provide useful, general guidelines about the typical progression of skills in children. It is my experience that parents and physicians have the greatest difficulty knowing what to expect for a child’s receptive language at any given age. It is important to have norms for developmental milestones, because delays in a child’s talking are a common developmental concern.

For convenience, Table 6–1 is divided into two age groupings, infant (0 to 12 months) and toddler-preschooler (15 months to 48 months). Table 6–2 lists the skills for the school-aged child (5 years or older). As children reach school age, assessment of motor skills becomes less important, and the focus is more on higher cognitive functions and specific academic skills.

Case 1

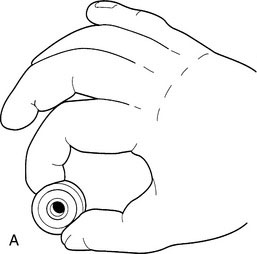

The physician removes the wrapped toy and gives the child a small pellet-sized candy and a glass bottle. She immediately pokes at the pellet with her index finger and picks it up with a smooth overhand pincer grasp (Fig. 6–12). The physician notices that the ulnar side of her hand rests on the table when she picks it up. The physician demonstrates putting another pellet inside the bottle, but the child does not imitate the action. The physician replaces the pellet and bottle with a crayon and paper. Susan does not scribble. The physician demonstrates scribbling, but Susan still is not interested.

Case 2

The functional inquiry and social and personal histories are noncontributory.

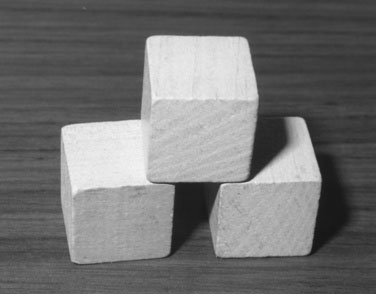

The physician praises his efforts and removes all but five of the blocks, which the physician sets up in a train design (Fig. 6–13). The physician says, “I am going to make a train. Here is a car, here is a car, here is a car, and see, it has a little chimney on top.” The physician takes the train apart and says, “Now you build me a train.” Steven puts four blocks in a line. The physician asks him where the chimney is, but he does not put it on. The physician then gives him three blocks and keeps three. The physician builds a three-block bridge design (Fig. 6–14) and then asks Steven to build a bridge just like it, leaving the sample bridge standing. He is unable to complete the design.

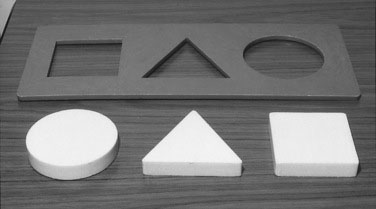

The physician removes the blocks and gets out a three-piece formboard, placing it as shown in Figure 6–7 with the matching puzzle pieces underneath the spot closest to the child. Steven promptly does the puzzle. The physician then removes the pieces and reverses the board (see Fig. 6–8). Steven immediately does the puzzle again and smiles with satisfaction. The physician removes that puzzle and gets out the five-shape geometric matching puzzle (see Fig. 6–9), showing Steven that the circle goes on top of the circle on the figure. The child, however, does not complete this puzzle.

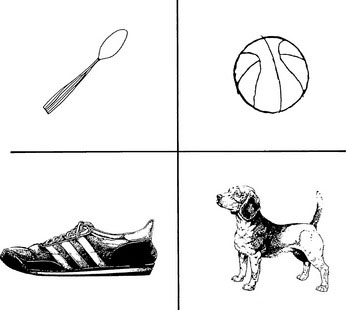

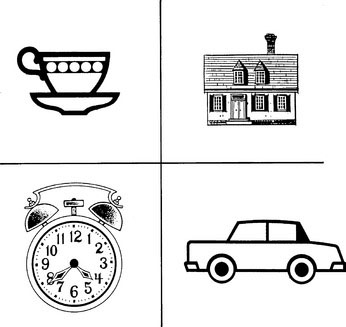

At this point, the physician says to Steven, “I would like to ask you some questions. Are you a boy or a girl?” He responds, “Me Steven.” The physician asks him what the rest of his name is, and he repeats, “Steven.” The physician asks him to name demonstrated parts of the body. He names only the nose and ears. The physician then asks him to point to his body parts, and he points successfully to seven of them. Next, the physician shows him picture vocabulary cards (see Figs. 6–4 and 6–5) and asks him to name the items shown. He names the house and the shoe but not the others. The physician names pictures and asks Steven to point them out. He points to most of them. The physician asks Steven to show “what we drink from” and to show “what we play with,” but he is unable to do so. The physician asks Steven to sing, “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” because his mother indicates that he can do so. He carries part of the tune. He does not sing the words, but when the physician leaves out a phrase, he fills it in.

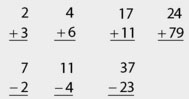

Case 3

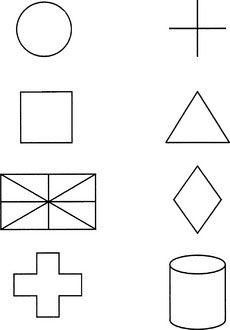

The physician has taken this part of the history with all three members of the family present. A review of Tommy’s self-help skills shows that he has no difficulty with dressing or running errands. He is popular with friends and successful at swimming and scouting. At this point, the physician asks the parents to leave, wanting to do some further interviewing and assessment with Tommy alone. The physician chats initially with Tommy about his favorite activities to put him at ease. The physician starts by having him do some drawing, asking him to draw the very best picture of a man that he can. He draws a picture with more than 20 items and many details. The physician then asks him to copy the geometric shapes shown in Figure 6–6. He does so without any difficulties. He prints the letters of the alphabet in capitals with no difficulty. He has no difficulty defining the following: football, tiger, eyelash, tap, roar, Mars. He recites the days of the week in proper order and describes the similarities and differences between a baseball and an orange. He gives correct answers to the following written problems:

Bricker D., Squires J., et al. Ages & Stages Questionnaires, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing, 1999.

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

Glascoe F.P. Collaborating with parents: using parents’ evaluation of developmental status to detect and address developmental and behavioral problems. Nashville, Tenn: Ellsworth & Vandermeer, 1998.

Illingworth R.S. Basic developmental screening 0–4 years. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1988.

Knobloch H., Pasamanick B. Gesell and Amatruda developmental diagnosis, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1974.

Rourke L.L., Leduc D.G., Rourke J.T. Rourke baby record 2000: collaboration in action. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:333-334.

-inch wide (

-inch wide (