Developmental Abnormalities

Beth Ann Drolet

Introduction

Developmental abnormalities of the skin are a diverse group of anomalies representing errors in morphogenesis. By definition, they are present at birth, although some are not evident in the neonatal period, but most present during infancy. They vary in severity from the inconsequential to the serious and, in some instances, represent a marker for significant extracutaneous anomalies.

Supernumerary mammary tissue

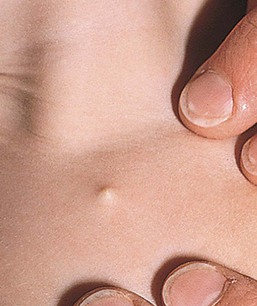

Accessory mammary tissue (supernumerary nipples, accessory nipple, polythelia, polymastia) may consist of true glandular tissue (accessory breasts), areola, nipples, or a combination thereof. It is often bilateral and found along the course of the embryologic breast lines, which run from the axilla to the inner thigh. Accessory nipples are the most common variant, occurring in as many as 2% of females, manifesting clinically as soft, brown, pedunculated papules (Fig. 9.1). In the newborn, the lesions are often very subtle, appearing as a light brown or pearly 1–3 mm macule. Familial occurrence has been reported.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually made clinically but may be confirmed by histologic demonstration of mammary tissue. An accessory nipple will show epidermal thickening, pilosebaceous structures, and smooth muscle, with or without true mammary glands.7 The differential diagnosis includes melanocytic nevus, neurofibroma, verruca, or skin tag.

Treatment

Complete surgical excision is usually recommended if there is glandular tissue because enlargement at puberty may cause pain and embarrassment. Small accessory nipples need not be excised. Breast carcinoma has also been reported in ectopic mammary tissue in an adult.8

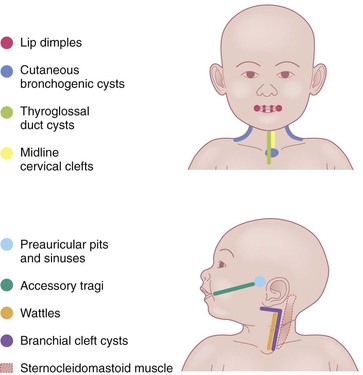

Preauricular pits and sinuses

The auricle is formed by fusion of six tubercles derived from the first and second branchial arches. Incomplete fusion may lead to entrapment of epithelium, forming cysts that communicate to the skin surface through sinuses.9 If the cyst and sinus are obliterated, a pit is left behind. Preauricular pits are common and may be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. They manifest as small depressions at the anterior margin of the ascending limb of the helix (Fig. 9.2).

Preauricular cysts present as tender swellings in the preauricular region; occasionally they are bilateral. If there is a sinus tract, fluid or pus may drain from a small opening just anterior to the ascending portion of the helix (Fig. 9.3). Most patients with preauricular cysts will have a history of recurrent infections.

Extracutaneous findings

The purported association of preauricular pits, accessory tragi, and sinuses with renal abnormalities is controversial.10 The most recent recommendations reserve renal ultrasound screening for patients with additional dysmorphic features, a family history of deafness, auricular and/or renal malformations, or a maternal history of gestational diabetes.11 Patients with preauricular pits or tags may have a higher incidence of hearing impairment, although studies regarding this are conflicting. Most studies do suggest screening for hearing deficits if the universal newborn hearing screen is not routinely performed.12

Diagnosis and treatment

The diagnosis is usually clinically apparent. The sinuses and cysts are lined by stratified squamous epithelium. Surgical excision of preauricular cysts and sinuses is indicated to prevent secondary infection. An experienced surgeon should perform the excision because the procedure may be complicated by multiple cysts along a tract that ends at the periosteum of the auditory canal.

Accessory tragi

The tragus is derived from the dorsal portion of the first branchial arch. Accessory tragi (erroneously referred to as preauricular ‘tags’) are always congenital and manifest as pedunculated, flesh-colored, soft, round papules usually arising on or near the tragus. They may occur anywhere from the preauricular region to the corner of the mouth, following the line of fusion of the mandibular and maxillary branches of the first branchial arch (Fig. 9.4). They may be bilateral and/or multiple. The same hearing and renal screening recommendations discussed above regarding preauricular pits should be followed. Accessory tragi are usually isolated defects, but may be associated with other developmental abnormalities of the first branchial arch.13 Goldenhar syndrome (oculoauriculovertebral syndrome) manifests as epibulbar dermoids, vertebral anomalies, and accessory tragi (Box 9.1).14

Diagnosis and treatment

The diagnosis is usually clinically apparent. Histologically, there are numerous tiny hair follicles with prominent connective tissue. A central core of cartilage is usually present.15 Accessory tragi should be removed by careful surgical dissection because most contain cartilage that may extend deeply, contiguous with the external ear canal. They are not skin tags and should not be tied off with suture material.16

Cervical tabs/wattles/congenital cartilaginous rests of the neck

Cervical tabs are soft, pedunculated, irregular nodules occurring on the neck along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. They are thought to be remnants of branchial arches and tend to occur along branchial arch fusion lines (Fig. 9.5). Histologically, they show lobules of mature cartilage embedded in collagen. The lesions do not extend deeply, but complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice because ligation may result in complications.17,18

Supernumerary digits (rudimentary polydactyly)

Supernumerary digits arise from the lateral surface of a normal digit. They are most common on the ulnar surface of the fifth digit, but may occur on any finger. They are congenital and may be bilateral or multiple. Some are small pedunculated papules, whereas others are normal-sized digits containing both cartilage and nail (Fig. 9.6). These lesions should be surgically excised and the associated nerve dissected if present. Ligating the supernumerary digit with suture material without completely removing the nerve may result in skin necrosis, infection, and painful neuromas in adult life.16

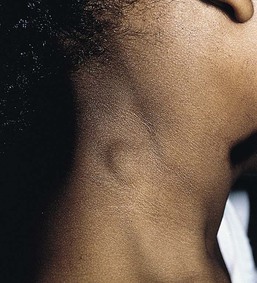

Branchial cysts, branchial clefts, and branchial sinuses

Branchial cysts are congenital malformations; however, they are not often apparent clinically until the first or second decade of life. They are painless, mobile, cystic swellings in the neck that may swell during respiratory tract infections. Most measure 1–2 cm, although they may be as large as 10 cm. Branchial cysts derived from the second branchial arch are the most common and are found on the lateral aspect of the upper neck, along the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 9.7).

Branchial cleft cysts derived from the first branchial arch are very rare and are located in the periauricular area or on the upper neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Definitive diagnosis is made by histologic examination of the lesions. Branchial cysts are lined by stratified squamous epithelium or, rarely, by ciliated columnar epithelium. Additionally, there is often abundant lymphoid tissue. Squamous cell carcinomas arising in these cystic lesions have been described in adults.19

Branchial sinuses and branchial clefts are thought to be remnants of the branchial cleft depressions. They are usually present at birth or noted during the first few years of life. The most common location is along the lateral lower third of the neck. Often a skin tag with a small amount of cartilage is associated with the pit. Branchial cleft anomalies should be surgically excised to prevent infection, with careful attention to the possibility of a true fistula connecting to the tonsillar oropharynx. Preoperative imaging may be necessary to exclude the possibility of true fistulae.

Thyroglossal duct cysts

Thyroglossal duct cysts are the most common cause of a congenital neck mass. They result from the persistence of a tract formed during the migration of the rudimentary thyroid gland from the base of the tongue to the anterior cervical regions. The most common location is on, or just lateral to, the midline neck in the area of the hyoid bone, but they may be found anywhere from the posterior tongue to the suprasternal notch. Most thyroglossal duct cysts present in childhood as an asymptomatic neck mass that moves upward with tongue protrusion or swallowing. Occasionally, ectopic thyroid tissue can be found in these cysts, and an association with thyroid cancer has been reported. The treatment is complete surgical excision in order to prevent growth and infection. Preoperative imaging with high-resolution ultrasound is important to confirm the diagnosis and identify the presence of a normal thyroid gland.20

Cutaneous bronchogenic cysts and sinuses

Bronchogenic cysts are usually found within the chest or mediastinum but may also occasionally be found in the skin. The most common cutaneous location is in the subcutaneous tissue at the suprasternal notch, but other locations include the lateral neck, scapula, and presternal area. Thus, these cysts should be included in the differential diagnosis of both lateral and midline neck masses. The cysts are congenital and usually apparent at birth. They are asymptomatic, small cystic swellings that will gradually enlarge over time and may discharge a mucoid material. These lesions are not usually associated with other malformations and do not connect to underlying structures.21,22 The diagnosis is made by histologic examination of the nodule or sinus. Bronchogenic cysts are lined by lamina propria and a pseudostratified columnar ciliated epithelium with goblet cells.23 The cyst wall may contain smooth muscle, mucus glands, and cartilage and lymphatic tissue may or may not be present.

The differential diagnosis includes branchial arch cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts, teratomas, and heterotopic salivary gland tissue. The treatment is complete surgical excision to prevent infection.

Median raphe cysts

Median raphe cysts (congenital sinus and cysts of the genitoperineal raphe, mucous cysts of the penile skin, parameatal cysts) are the consequence of incomplete fusion of the ventral aspect of the urethral or genital folds. The cysts can occur at any site on the ventral surface of the male genital region, including the parameatus, glans penis, penile shaft, scrotum, or perineum. In most cases they remain asymptomatic and do not interfere with urinary or sexual function. Rarely they can enlarge or become superinfected. In infancy they manifest as small, soft, flesh-colored papules along the ventral aspect of the penis in the line of the median raphe, however, they may enlarge during adolescence (Fig. 9.8). The cysts are lined with pseudostratified columnar epithelium, except at the distal penis, where they have stratified epithelium.24

Ventral midline clefts/defects

Supraumbilical cleft

Disruption of abdominal wall fusion causes midline defects of variable degree, often involving the heart and sternum, as well as the abdominal wall. Supraumbilical raphes are linear, midline clefts that occur superior to the umbilicus (Fig. 9.9). A well-described association of supraumbilical raphe and/or sternal clefting has been described in association with hemangiomas and PHACE syndrome (see Chapter 21).25–27

Midline cervical clefts

This rare abnormality of the midline ventral neck presents as a small skin tag superiorly with a linear, vertically oriented atrophic patch. At the inferior aspect of the patch there is often a small sinus containing ectopic salivary tissue.28 Midline cervical clefts can be associated with cleft lip, palate, mandible, chin, tongue, or midline neck hypoplasia.29 Excision with serial Z-plasties is the treatment of choice.

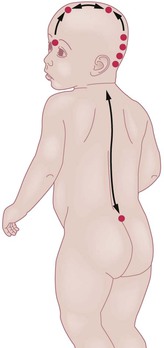

Cutaneous signs of neural tube dysraphism

The skin and the nervous system share a common ectodermal origin. Separation of the neural and cutaneous ectoderm occurs early in gestation, at the same time the neural tube is fusing. This shared embryologic origin explains the simultaneous occurrence of congenital malformations of the skin and neural tube dysraphism, which is an incomplete closure or defective fusion. Open neural tube defects are often large and diagnosed in utero or at birth; however, closed or occult neural tube defects often present solely with congenital abnormalities of the skin overlying the defect. It is important to recognize these cutaneous markers and screen with the appropriate radiologic imaging techniques. A general knowledge of embryology and formation and closure of the neural tube is useful in identifying which cutaneous markers are highly indicative of underlying defects. The neural tube is no longer believed to fuse in a zipper-like fashion, but rather in a segmental, noncontiguous pattern.30 This theory is supported by the clinical observation of cutaneous ‘hotspots’ for dysraphic conditions. Each hotspot corresponds to a fusion point of the various segments of the neural tube (Fig. 9.10).

Cranial dysraphism

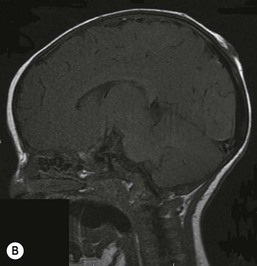

Cephaloceles/cutaneous neural heterotopias

The term cutaneous neural heterotopia was introduced to describe ectopic leptomeningeal or glial tissue found in the subcutaneous tissue or dermis of the skin. These malformations are the result of incomplete or faulty closure of the neural tube. Cephalocele is the general term for congenital herniation of intracranial structures through a cranial defect. Encephalocele is herniation of both glial and meningeal tissue. Meningoceles are cephaloceles in which only the meninges and cerebrospinal fluid herniate through a calvarial defect. Large encephaloceles and meningoceles pose no diagnostic problem and are usually easily diagnosed prenatally or at birth. Smaller or atretic encephaloceles and meningoceles may be mistaken for cutaneous lesions such as hematomas, hemangiomas, aplasia cutis, dermoid cysts, or inclusion cysts. Several terms have been used to describe these smaller lesions (Box 9.2). These various classifications were derived from the amount and type of neural tissue present, as well as the degree of connection to the central nervous system. Unfortunately, it is not possible to predict the degree of CNS connection on clinical grounds alone. Therefore, all congenital exophytic scalp nodules should be evaluated thoroughly, as 20–37% of congenital, nontraumatic scalp nodules connect to the underlying central nervous system.31,32

Cutaneous findings

Cephaloceles occur in the frontal, parietal, and occipital regions. They are usually midline, although they may also be found 1–3 cm lateral to the midline. Small cephaloceles are clinically heterogeneous; their appearance dictated by the type and amount of cutaneous ectoderm overlying the lesion. They may be covered with normal skin, or have a blue, translucent, or glistening surface. There is usually a disruption of the surrounding and overlying normal hair pattern. They are soft, compressible, round nodules that increase in size when the baby cries or with a Valsalva maneuver.

The association of a congenital scalp mass with other cutaneous abnormalities makes the diagnosis of cranial dysraphism highly suspicious. Stigmata include hypertrichosis, or the ‘hair-collar sign,’ capillary malformations, and cutaneous dimples and sinuses.33,34 The hypertrichosis may overlie the nodule, surround a small sinus, or encircle the nodule (hair-collar sign). A hair collar is defined as a congenital ring of hair that is usually denser, darker, and coarser than the normal scalp hair. When found encircling an exophytic scalp nodule, it is highly suggestive of cranial dysraphism (Figs 9.11, 9.12).33,34 The hair-collar sign may be found in association with encephaloceles, meningoceles, atretic encephaloceles, atretic meningoceles, and heterotopic brain tissue. A hair collar may also be seen with some lesions of aplasia cutis; thus this sign is not entirely specific.35 Cranial neural tube defects may also be associated with overlying red, blanchable patches that represent capillary malformations. The combination of a hair-collar sign and capillary malformation surrounding a congenital scalp lesion is almost always indicative of a dysraphic condition (Fig. 9.11).34

Extracutaneous findings and diagnosis

From a clinical standpoint, encephaloceles, meningoceles, atretic cephaloceles, and heterotopic brain tissue are virtually impossible to differentiate. All congenital midline scalp nodules carry a significant risk of intracranial connection and should have radiologic imaging studies performed before surgical removal to prevent complications such as meningitis. Membranous aplasia cutis congenita (ACC) has many overlapping clinical features (including the hair-collar sign); in addition, the loose fibroconnective tissue seen histologically is very similar to the changes observed surrounding encephaloceles.33 The presence of a palpable nodule within a lesion of ACC, however, is uncommon and should always prompt further evaluation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most sensitive method for detecting small cephaloceles with intracranial connections.

Differential diagnosis and management

Included in the differential diagnoses of congenital scalp nodules are pilomatrixoma, epidermoid cyst, lipoma, osteoma, eosinophilic granuloma, hemangioma, sinus pericranii, dermoid cyst, leptomeningeal cyst, and cephalohematoma.36 Surgical correction is indicated for all cephaloceles.

Nasal gliomas

Gliomas are rests of ectopic neural tissue and differ from frontal encephaloceles in that they do not have a patent intracranial communication. The lesions may be external, intranasal, or combined. Clinically, they are firm, noncompressible, nontender skin-colored to red-purple nodules at the root of the nose. Gliomas may be covered with nasal mucosa or normal skin; they are often associated with telangiectasia and misdiagnosed as hemangiomas. They may widen the nasal bone, giving the appearance of hypertelorism. They are congenital and do not proliferate. Additionally, they do not respond to oral steroids or propranolol, which helps to differentiate them from hemangiomas. Immediate neurosurgical referral is required for surgical removal and reconstruction.

Cranial dermoid cysts and sinuses

Dermoid cysts are congenital subcutaneous lesions that are distributed along embryonic fusion lines. The cysts may occur within the fusion lines of the facial processes or along the neural axis. They represent faulty development and may include both epidermal and dermal elements.

Cutaneous findings

Although dermoid cysts are always congenital, they may not be noted until early childhood, when they begin to enlarge. They can occur anywhere on the face, scalp, or spinal axis but are most frequently seen overlying the anterior fontanelle, at the junction of the sagittal and coronal sutures on the scalp, on the upper lateral region of the forehead within or near the eyebrow, and in the submental region.31,37–40 They are firm, nontender, noncompressible, blue or skin-colored nodules measuring 1–4 cm (Figs 9.13, 9.14). They do not transilluminate or enlarge with a Valsalva maneuver. The overlying skin is normal, unless there is an external connection in the form of a pit or a sinus. Dermoid cysts often adhere to the underlying periosteum and may feel like abnormalities of the bone.

Dermal sinuses are 1–5 mm tracts that typically connect a dermoid cyst to the skin surface. They are midline and are found on the nose, occipital scalp (Fig. 9.15) and anywhere along the spinal axis. They may become clinically apparent when they become infected and drain purulent material. A small tuft of hair is often found protruding from the orifice. If the sinus and/or cyst communicates directly with the central nervous system, the patient is at risk for meningitis. The sinus serves as an occult portal of entry for bacteria, often causing recurrent meningitis that is culture-positive for skin flora. Staphylococcus aureus meningitis should be considered secondary to a dermal sinus until proved otherwise, and a thorough search for a cutaneous fistula should be carried out, which may necessitate shaving the scalp hair.41 All midline dermal sinuses should have radiologic imaging prior to surgical excision. Probing these lesions is contraindicated, given the potential risk of meningitis.

Extracutaneous findings

Midline or nasal dermoid cysts are of the greatest concern because 25% have an intracranial connection.31 Nasal dermoid cysts may occur anywhere from the glabella to the tip of the nose; a nasal pit or sinus is present in about half the cases.37 The pit often leads caudally to a dermal sinus and eventuates in a cyst that may be either external or within the nasal bones. If the dermoid cyst connects to the central nervous system, cerebrospinal fluid may drain from the sinus. As with nasal gliomas, the patient may have the appearance of hypertelorism if the cyst has widened the nasal bones. Nasal dermoids should always be excised, because over time, they enlarge and damage the nasal bones. Dermoid cysts that are not midline should also be excised because they have the potential for infection. Dermoids of the lateral eyebrow area do not have central nervous system connections and may be surgically excised, either directly or using an endoscopic approach via a scalp incision to avoid facial scarring (Fig. 9.14). Lateral brow dermoids appear deceptively superficial, but most are actually located beneath muscle, so that either removal must be via an endoscopic approach or the surgeon must be prepared to dissect through the muscle to remove the cyst.

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis is made by histologic examination of the lesions. Dermoids cysts are usually found in the subcutaneous tissue and are lined by stratified squamous epithelium, often containing hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and sweat glands. The lumen may contain keratin, lipid, and hair. Radiologic imaging is a very sensitive screening method and should be undertaken prior to surgical intervention. Currently, the most sensitive study is MRI. Computed tomography (CT) may better delineate bony defects and may also be necessary for surgical planning, especially in the nasal region. Although plain radiographs were used extensively in the past, they are not sensitive and should not be used for screening.

Spinal dysraphism

Spinal dysraphism, or incomplete closure of the spinal axis, encompasses many congenital anomalies of the spine. Larger, open defects, such as meningomyeloceles, are usually obvious at birth and fall within the purview of the neurosurgeon. However, small or occult malformations covered with skin may have subtle signs and be asymptomatic. Early diagnosis is imperative, as it may prevent irreversible neurologic damage caused by tethering of the spinal cord. A diagnosis of occult spinal dysraphism is often suspected solely on the basis of overlying cutaneous findings, particularly in the newborn. Cutaneous markers are found in 50–90% of patients with spinal dysraphism.42–51

Cutaneous findings

The cutaneous lesions that should alert the physician to an underlying occult spinal dysraphism are listed in Box 9.3. Most are found on or near the midline in the lumbosacral region; however, similar markers in the cervical or thoracic regions may also be indicative of an underlying malformation. The literature suggests that certain skin lesions are more indicative than others of underlying malformation.42–53 Tavafoghi and colleagues51 reviewed 200 cases of spinal dysraphism and found that 102 had cutaneous signs. Other studies have documented an even higher incidence of cutaneous malformations (71–100%). Unfortunately, no prospective studies have been carried out to determine what percentage of children with cutaneous anomalies overlying the spinal axis has occult dysraphism.

Congenital cutaneous anomalies of the lumbosacral region should be evaluated in the context of a full history and physical examination, particularly in the older child. The history should include questions about additional congenital malformations, family history of neural tube defects, weakness or pain in the lower extremities, abnormal gait, scoliosis, difficulties with toilet training or incontinence, recurrent urinary tract infections, and recurrent meningitis. The vertebrae should be palpated for any defects or abnormalities. Examination of the rectum and genitalia is also indicated, as there are often related congenital abnormalities of the urogenital system.54–56 The gluteal cleft should be examined carefully for small acrochordons or sinuses; it should be straight and the buttocks symmetric. If the gluteal cleft deviates, it is suggestive of an underlying mass such as a lipoma or meningocele. Examination of the lower extremities is important in older children because they may have trophic changes secondary to nerve damage.

Hypertrichosis

Localized lumbosacral hypertrichosis, or ‘hairy patch,’ is usually present at birth. The hair may be dark or light. The texture of the hair can vary but is frequently described as silky (faun tail nevus). The hypertrichosis is often V-shaped and poorly circumscribed. Prominent hypertrichosis is commonly associated with other cutaneous stigmata of spinal dysraphism and is highly indicative of a spinal defect. However, hypertrichosis in the lumbosacral region can also be a normal finding, especially in certain ethnic or racial groups, and it may be difficult to decide whether or not further evaluation is indicated. Referral to a neurologist or neurosurgeon for a more complete neurologic examination may be a prudent measure in these cases.

Lipomas

Lipomas associated with spinal dysraphism are thought to be congenital and are also highly indicative of an underlying defect. Unlike acquired lipomas, they may be poorly circumscribed and feel more like an area of increased subcutaneous fat than a discrete lesion. They are frequently associated with a vascular stain or infantile hemangioma. The lipoma may lie in the dermis or the spinal canal, and often penetrates from the dermis through a vertebral defect into the intraspinal space (lipomyelomeningocele). Intraspinal lipomas are a common cause of tethered cord. Appropriate radiologic investigation of lumbosacral lipomas must be performed before surgical excision, and a neurosurgeon should be involved as small intraspinal connections may be missed, even with the most sensitive radiologic imaging.

Hemangiomas, telangiectasias, and capillary malformations

Infantile hemangiomas are proliferative vascular tumors that may be present at birth or develop in the first months of life. In 1986, Goldberg and coworkers described five children with large sacral hemangiomas and several other associated abnormalities.55 Three of the five had spinal dysraphism (lipomyelomeningocele). In 1989, Albright and colleagues42 reported seven infants with lumbar hemangiomas and a tethered spinal cord. Although several subsequent reports have supported this association, the true risk of spinal dysraphism with solitary infantile hemangiomas has been debated. Much of the controversy stems from imprecise terminology (‘capillary hemangiomas’) and the lumping of vascular stains with infantile hemangiomas. A recent prospective study helped to clarify the issue, demonstrating a 52% risk of spinal dysraphism with infantile hemangiomas >2.5 cm in the midline lumbosacral region.57 Intraspinal lipomas were the most frequent association, but intraspinal hemangiomas were found in 45% of the cases. Hemangiomas associated with spinal dysraphism are usually large (>4 cm) and overlie the midline of the lumbar or sacral region (Figs 9.16, 9.17). There is often a small skin defect or ulceration58 within the center of the hemangioma. The hemangiomas may be associated with other cutaneous stigmata, such as lipoma, acrochordon, or dermal sinus. In addition, hemangiomas may be observed in a constellation of congenital malformations seen in the caudal regressions syndromes. Although various acronyms have been coined to describe this constellation of abnormalities (PELVIS syndrome, SACRAL syndrome, and LUMBAR syndrome), they all represent the same clinical spectrum and manifest as lumbosacral hemangioma, anogenital abnormalities, and spinal dysraphism. These cases are difficult to manage because the hemangiomas can ulcerate, and surgical repair of the tethered cord often may have to be delayed until the hemangioma partially regresses.

Reports of telangiectatic patches are most likely describing nascent or partially regressed hemangiomas. Enjolras and colleagues59 reported two patients with cervical spinal dysraphism with an overlying capillary malformation (port-wine stain), but spinal dysraphism associated with a midline, lumbosacral capillary malformation without additional clinical findings is probably uncommon. Two small studies have shown a low, although genuine, incidence of spinal dysraphism associated with a solitary capillary malformation of the lumbosacral region.60,61 Further investigation is needed to completely clarify the need for imaging in these infants. A neurologic consultation may be warranted.

Dimples, sinuses, aplasia cutis, and congenital scars

Lumbosacral dimples are common, but can occasionally be a sign of spinal dysraphism.62,63 Most infants with coccygeal or lower sacral dimples falling within the gluteal crease, are normal.64 Dimples that are deep, large (>0.5 cm), located in the superior portion or above the gluteal crease (>2.5 cm from the anal verge), or associated with other cutaneous markers should be radiologically imaged (Fig. 9.18).61 Deep or draining dimples may actually be dermal sinuses, communicating directly with the spinal canal. They may also be located off the midline, on the buttock (Fig. 9.19).65 These lesions should not be probed, but instead should prompt MRI studies and neurosurgical consultation.

Aplasia cutis has rarely been reported in the lumbosacral region and in that site may be associated with underlying spinal dysraphism (Fig. 9.20).43 Scar-like defects have also been described in patients with spinal dysraphism, and may in fact be a variant of aplasia cutis.55 The scar-like regions found in lumbosacral hemangiomas may represent a similar phenomenon.

Acrochordons, tails, and pseudotails

Acrochordons are small skin-covered sessile or pedunculated papules or nodules (Fig. 9.21). Histologically they are composed of epidermis and a dermal stalk. A true human tail (persistent vestigial tail) is rare and is differentiated from a pseudotail and an acrochordon by the presence of a central core of mature fatty tissue, small blood vessels, bundles of muscle fibers, and nerve fibers. A pseudotail is a stump-like structure considered to be a hamartoma composed of fatty tissue and, often, cartilage. Clinically, these lesions are difficult to distinguish and all have been associated with spinal dysraphism.45,47,51,55,66 Preoperative radiologic investigation is indicated in all cases.

Diagnosis

A definitive diagnosis of spinal dysraphism is made only at surgery. Radiologic imaging provides a sensitive screening method. MRI remains the gold standard; high-resolution ultrasound is a noninvasive alternative in an infant of less than 3 months of age, but its sensitivity is low, making it an unreliable screening tool.67–73 It is often useful to speak to the radiologist before ordering the examination because the technology is changing rapidly and will vary by institution. Urodynamic studies are increasingly being used as another modality for assessing spinal cord function in settings where radiologic findings are equivocal.74

Aplasia cutis

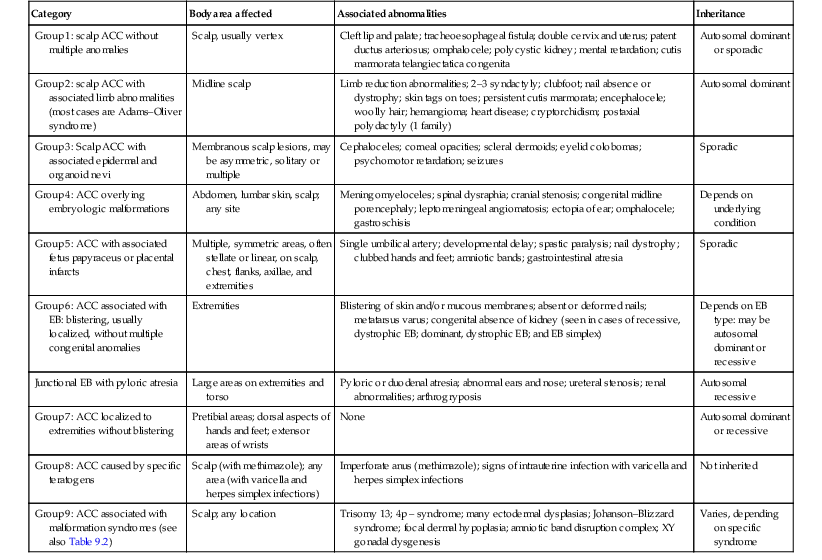

Aplasia cutis is a general term used to describe focal, congenital defects of the skin. The condition is rare and its true incidence is unknown. Although several theories have been proposed as to its pathogenesis, most authors believe that aplasia cutis has no single underlying cause but is rather a clinical finding, resulting from a variety of events that occur in utero. Several classifications of aplasia cutis have been proposed (Table 9.1).75

TABLE 9.1

A classification of aplasia cutis congenita

| Category | Body area affected | Associated abnormalities | Inheritance |

| Group 1: scalp ACC without multiple anomalies | Scalp, usually vertex | Cleft lip and palate; tracheoesophageal fistula; double cervix and uterus; patent ductus arteriosus; omphalocele; polycystic kidney; mental retardation; cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita | Autosomal dominant or sporadic |

| Group 2: scalp ACC with associated limb abnormalities (most cases are Adams–Oliver syndrome) | Midline scalp | Limb reduction abnormalities; 2–3 syndactyly; clubfoot; nail absence or dystrophy; skin tags on toes; persistent cutis marmorata; encephalocele; woolly hair; hemangioma; heart disease; cryptorchidism; postaxial polydactyly (1 family) | Autosomal dominant |

| Group 3: Scalp ACC with associated epidermal and organoid nevi | Membranous scalp lesions, may be asymmetric, solitary or multiple | Cephaloceles; corneal opacities; scleral dermoids; eyelid colobomas; psychomotor retardation; seizures | Sporadic |

| Group 4: ACC overlying embryologic malformations | Abdomen, lumbar skin, scalp; any site | Meningomyeloceles; spinal dysraphia; cranial stenosis; congenital midline porencephaly; leptomeningeal angiomatosis; ectopia of ear; omphalocele; gastroschisis | Depends on underlying condition |

| Group 5: ACC with associated fetus papyraceus or placental infarcts | Multiple, symmetric areas, often stellate or linear, on scalp, chest, flanks, axillae, and extremities | Single umbilical artery; developmental delay; spastic paralysis; nail dystrophy; clubbed hands and feet; amniotic bands; gastrointestinal atresia | Sporadic |

| Group 6: ACC associated with EB: blistering, usually localized, without multiple congenital anomalies | Extremities | Blistering of skin and/or mucous membranes; absent or deformed nails; metatarsus varus; congenital absence of kidney (seen in cases of recessive, dystrophic EB; dominant, dystrophic EB; and EB simplex) | Depends on EB type: may be autosomal dominant or recessive |

| Junctional EB with pyloric atresia | Large areas on extremities and torso | Pyloric or duodenal atresia; abnormal ears and nose; ureteral stenosis; renal abnormalities; arthrogryposis | Autosomal recessive |

| Group 7: ACC localized to extremities without blistering | Pretibial areas; dorsal aspects of hands and feet; extensor areas of wrists | None | Autosomal dominant or recessive |

| Group 8: ACC caused by specific teratogens | Scalp (with methimazole); any area (with varicella and herpes simplex infections) | Imperforate anus (methimazole); signs of intrauterine infection with varicella and herpes simplex infections | Not inherited |

| Group 9: ACC associated with malformation syndromes (see also Table 9.2) | Scalp; any location | Trisomy 13; 4p – syndrome; many ectodermal dysplasias; Johanson–Blizzard syndrome; focal dermal hypoplasia; amniotic band disruption complex; XY gonadal dysgenesis | Varies, depending on specific syndrome |

ACC, aplasia cutis congenita; EB, epidermolysis bullosa.

Modified from Frieden IJ. Aplasia cutis congenita: A clinical review and proposal for classification. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986; 14:646–660.

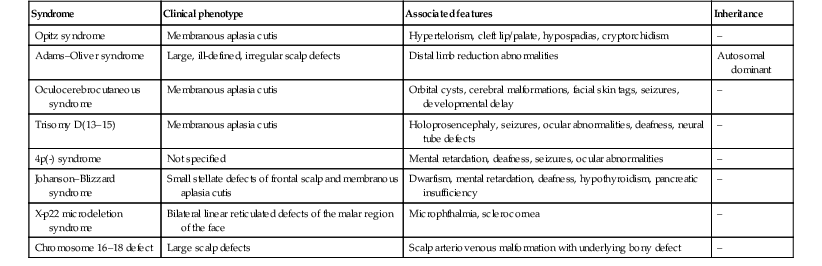

When evaluating a newborn with aplasia cutis, particular attention should be given to the morphology and the distribution of the defects, because this may be helpful in determining the etiology, possible associated malformations, and prognosis (Table 9.2). For example, infants with large (>3 cm), angular defects of aplasia cutis on the bilateral extremities have generalized increased skin fragility, the result of a genetic deficiency, and almost all have been classified as having epidermolysis bullosa. This is a lifelong affliction and will have immediate implications for the care of the infant. Large, irregular scalp defects may be seen with trisomy 13 (Fig. 9.22). Table 9.3 correlates the clinical findings with the proposed etiology and associations.

TABLE 9.2

Associated malformations and chromosomal defects reported with aplasia cutis

| Syndrome | Clinical phenotype | Associated features | Inheritance |

| Opitz syndrome | Membranous aplasia cutis | Hypertelorism, cleft lip/palate, hypospadias, cryptorchidism | – |

| Adams–Oliver syndrome | Large, ill-defined, irregular scalp defects | Distal limb reduction abnormalities | Autosomal dominant |

| Oculocerebrocutaneous syndrome | Membranous aplasia cutis | Orbital cysts, cerebral malformations, facial skin tags, seizures, developmental delay | – |

| Trisomy D(13–15) | Membranous aplasia cutis | Holoprosencephaly, seizures, ocular abnormalities, deafness, neural tube defects | – |

| 4p(-) syndrome | Not specified | Mental retardation, deafness, seizures, ocular abnormalities | – |

| Johanson–Blizzard syndrome | Small stellate defects of frontal scalp and membranous aplasia cutis | Dwarfism, mental retardation, deafness, hypothyroidism, pancreatic insufficiency | – |

| X-p22 microdeletion syndrome | Bilateral linear reticulated defects of the malar region of the face | Microphthalmia, sclerocornea | – |

| Chromosome 16–18 defect | Large scalp defects | Scalp arteriovenous malformation with underlying bony defect | – |

TABLE 9.3

Correlation of clinical findings with proposed etiology and associations in aplasia cutis

| Clinical phenotype | Proposed etiology | Associations |

| Cranial and facial membranous aplasia cutis | Developmental | Organoid nevi |

| Truncal, stellate aplasia cutis | Vascular disruption | Fetus papyraceus, placental insufficiency, gastrointestinal atresia |

| Extremity, angulated defects | Increased skin fragility | Epidermolysis bullosa |

| Small scar-like defects | Maternal infections | Varicella, herpes simplex virus infections |

| Cranial large, midline irregular defects | Developmental, genetic | Bone defects, hydrocephalus, arteriovenous fistula, sinus thrombosis |

| Reticulated facial lesions | Chromosomal abnormality | X-p22 deletion syndrome |

Cutaneous findings

Membranous aplasia cutis is the most common form of the condition. It occurs primarily on the scalp, but may also be seen on the lateral aspects of the face (focal facial dermal hypoplasia). The lesions are usually small (<1 cm), oval, or round and are well-circumscribed, with a ‘punched-out’ appearance (Fig. 9.23). At birth, the surface is atrophic, often thin, glistening, and membrane-like. Scar-like lesions in the same configuration are more common in older children. Rarely, the lesions may be bullous at birth, containing a thick, clear fluid (Fig. 9.24). The bullous lesions may drain spontaneously and reform, eventually flattening to the more typical appearance. Defects of membranous aplasia cutis are often multiple, occurring in a linear configuration. The most common location is at the vertex of the scalp, but they may also be found anterior to the vertex, off the midline on the lateral parietal scalp, or even extending down onto the forehead along a line from the lateral forehead to the lateral edge of the eyebrows. Rarely, lesions of membranous aplasia cutis occur on the face, in a line extending from the preauricular region to the angles of the mouth.76 The term focal facial dermal hypoplasia has been used to describe these lesions (Fig. 9.25). Lesions of temporal aplasia cutis may be associated with Setleis syndrome and found with additional facial anomalies. Most reports of membranous aplasia cutis are sporadic, although there are well-documented patients with autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive patterns of inheritance.77,78 While the exact etiology of these lesions is unknown, the configuration, distribution, and clinical appearance would suggest incomplete closure of embryonic fusion lines, rather than vascular interruption or trauma to the skin.76 A case of membranous aplasia cutis was detected by prenatal ultrasound at 27 weeks’ gestation. A protruding, round, cystic lesion was noted at the vertex of the scalp. The lesion resolved spontaneously at 37 weeks’ gestation, and a small oval lesion of membranous aplasia cutis was found in the identical location at birth.79

Irregular, large (>3 cm), or stellate scalp defects of aplasia cutis are much less common, but may occur along the midline of the scalp (Fig. 9.26). These defects are more commonly familial and often associated with large underlying bony defects.80 They have a high risk of infection and sagittal sinus thrombosis or hemorrhage. Abnormalities of the underlying venous system and arteriovenous malformations may be associated with these types of defects. Radiologic imaging with particular attention to the vasculature is recommended, as hemorrhagic complications and death have been reported.81

Aplasia cutis of the trunk

When the term ‘aplasia cutis’ is used in the most literal sense, this condition is found overlying abdominal malformations such as gastroschisis and omphalocele. Extensive truncal and limb defects have been associated with fetus papyraceus.82,83 These defects differ clinically from membranous aplasia cutis. They are large, linear, or stellate erosions involving the lateral aspects of the trunk and extensor surfaces of the extremities (Fig. 9.27). Frequently, they are bilateral and symmetric. It is theorized that these defects are the result of placental infarction after the death of a twin fetus (Fig. 9.28), which would explain their symmetric distribution. These types of cutaneous lesions may also be associated with gastrointestinal malformations, particularly bowel atresia, which is also thought to be a consequence of early ischemia.84 Additional extracutaneous findings include neurodevelopmental delay, intracranial hemorrhage, cardiac and arterial anomalies, renal cortical necrosis, and neonatal Volkmann ischemic contracture.85,86 Similar truncal defects have been seen in patients with pale or small placentas, and several have also been reported without mention of the placenta.85 Irregular defects of the extremities and trunk have been reported with blistering of the skin (Bart syndrome); however, these are now considered to be a form of epidermolysis bullosa.75,87

Reticulated linear skin defects of the malar region of the face have been reported as part of the X-p22 microdeletion syndrome (see Chapter 29). All reported cases have been female, suggesting that the deletion may be lethal in males. Severity varies in females from relatively mild facial scarring to major organ malformations. The syndrome is also associated with microphthalmia and sclerocornea.88–90

Pathogenesis

Several theories have been proposed as to the etiology of aplasia cutis. Incomplete closure of the neural tube may explain midline lesions, and incomplete closure of embryonic fusion lines may explain the lateral membranous aplasia cutis lesions.76 Vascular insufficiency to the skin may result from placental insufficiency or thromboplastic material from a fetus papyraceus. Amniotic membrane adhesions, teratogenic agents, and intrauterine infections have also been implicated. Based on the heterogeneity of the associated findings, a unifying theory is unlikely.

Extracutaneous findings

Although ACC has been associated with several syndromes, the great majority of lesions occur as a solitary cutaneous finding. The lesions of membranous aplasia cutis most commonly occur as an isolated defect and usually require no further investigation. Even small underlying bony defects usually heal spontaneously. However, there are exceptions. Any lesion of aplasia cutis with a palpable lump within it should prompt further evaluation (see above). Midline lesions occurring at sites between the vertex and occiput are less common, and have a greater risk of underlying defects and/or sinus connections (Fig. 9.29). Larger lesions of aplasia cutis with large underlying bony defects need prompt imaging studies to assess for underlying CNS defects or connections, as well as evidence of close proximity to the sagittal sinus, as life-threatening hemorrhage has been reported in this setting and prompt surgical intervention may be required. These stellate or necrotic midline lesions have also been described in association with terminal transverse limb defects, the so-called Adams–Oliver syndrome. Familial cases of Adams–Oliver syndrome have been described and attributed to various mutations affecting cell-cell or cell-matrix. A very rare, distinctive subtype of aplasia cutis has been associated with X-p22 microdeletion syndrome. These infants have superficial and reticulate erosions over the bilateral cheeks and neck.91 Tables 9.2 and 9.3 list some of the associated malformations and chromosomal defects reported with aplasia cutis.92

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually based on clinical data, although histologic examination of the defects may help to confirm the diagnosis. Membranous aplasia cutis has the most characteristic histologic findings; the epidermis is atrophic and flattened, and the normal superficial dermis is replaced by loose connective tissue.76 The normal adnexal structures are small or completely absent.93 If a hair collar is present, then the edge of the specimen will have clustered, hypertrophic hair follicles. Other subtypes of aplasia cutis show superficial scarring with loss of normal adnexal structures. Increased levels of acetylcholinesterase and α-fetoprotein have been reported in the amniotic fluid of mothers with children with aplasia cutis.94,95

Differential diagnosis

Postnatal trauma caused by forceps or monitoring devices, Goltz syndrome, epidermolysis bullosa, and incontinentia pigmenti can be confused with aplasia cutis.

Prognosis and management

If the lesion is ulcerated at birth, the area should be cleansed daily and a topical petrolatum-based ointment applied until complete healing has occurred. Secondary infection is uncommon except in cases of extensive scalp aplasia cutis. Small superficial skin ulcers usually heal in the first months of life. Similarly, small defects of the underlying bone usually ossify completely without treatment.96 Most small defects will become inconspicuous as the child’s scalp grows, but larger lesions may cause significant visible deformity, and almost all will result in localized alopecia. Surgical excision may be considered later in life. Lesions that are midline and posterior to the vertex of the scalp should be imaged to rule out a dermal sinus. If the defect is large, stellate in configuration, or associated with additional cutaneous abnormalities or bone defect, MRI should be considered before surgical resection.

Very large (>3 cm) stellate scalp defects (Fig. 9.26) can affect the galea, the pericranium, the bone, and the dura mater, and these lesions are at risk for infection and severe hemorrhage. They may take several months to heal and may require surgical intervention. In addition, these defects often have abnormalities of the intracranial vascular system. Consequently, radiologic investigation is indicated and required before surgical correction is undertaken because severe hemorrhage and even death has been reported after repair of large defects.97–100 The defects associated with fetus papyraceus heal remarkably well, leaving hypopigmented scars, and do not usually require surgical correction.

Cutaneous dimples

Cutaneous dimples are small depressions or pits in the skin that measure 1–4 mm. Dimples may occur at any location, but are more common over bony prominences such as the elbow, knee, acromion, and sacral region.101 Cutaneous dimples may be normal, particularly in some locations such as the face. Symmetric shoulder dimples over the acromion or supraspinous fossae may be familial and inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern.101–104 Cutaneous dimples have been associated with a wide variety of genetic disorders (Box 9.4).105–108 Dimples may be the result of aberrant fetal positioning in early gestation in patients with congenital skeletal dysplasia.108 Lip dimples or lip pits may be an isolated defect or associated with Van der Woude syndrome, where they are bilateral, on the lower lip, and associated with cleft lip or palate (see Chapter 30). Usually, dimples do not require treatment, as they are small and not cosmetically disfiguring. Surgical excision may be indicated for lip dimples, as they can communicate with underlying minor salivary glands and have recurrent inflammation. Deep dimples in certain locations such as overlying the spine or on the buttock may actually represent superficial manifestations of an underlying sinus tract, requiring evaluations, as discussed above.

Adnexal polyp

An adnexal polyp is a small, congenital papule found on the chest, usually on, or just medial to, the areola of the nipple. The lesions are small (1–2 mm), flesh-colored, firm, pedunculated papules with a smooth surface (Fig. 9.30). Older lesions may have a superficial crust. Histologically, the lesions are composed of adnexal structures. Hair follicles, vestigial sebaceous glands, and eccrine glands are present in the center of the lesion.107 The lesions appear to fall off spontaneously soon after birth.

Developmental anomalies of the umbilicus

The umbilicus is a scar that represents the site of attachment of the umbilical cord in the fetus. The umbilical cord usually separates from the umbilicus at 1–8 weeks of life. Abnormal position of the umbilicus is often associated with other congenital abdominal wall defects such as omphalocele and gastroschisis. Persistent drainage or a mass at the site are signs of infection or persistent embryologic remnants.

Anomalies of the urachus

The urachus is the remnant of the regressed allantois running from the apex of the bladder to the umbilicus. If this structure fails to regress, leaving complete patency, a fistula forms between the bladder and the umbilicus. This is manifested by urine draining from the umbilicus. Partial patency of the urachus will result in a cystic dilation in which both ends are obliterated, forming an urachal cyst. Urachal cysts may occur at any point along the course of the urachus but do not communicate with the umbilicus or bladder. They present as tender, midline swellings between the umbilicus and the symphysis pubis. If the urachus is only patent at the umbilicus, an urachal sinus forms, which is usually associated with a proximal urachal cyst presenting as a cystic swelling at the umbilicus (Fig. 9.31).

Anomalies of the omphalomesenteric duct

The omphalomesenteric duct connects the ileum to the umbilicus. This duct usually regresses during the 5th to 9th weeks’ gestation, leaving a fibrous cord. Failure of normal obliteration will result in a range of congenital anomalies, depending on the extent and the site of persistent patency. The entire duct may be patent, forming a fistula between the ileum and the umbilicus; this presents during infancy with a red nodule at the umbilicus with a surrounding fistula. Fecal material may discharge from the fistula, often resulting in irritation of the surrounding skin. If intermediate portions of the duct remain patent, an omphalomesenteric cyst forms. If the cyst is located toward the periphery of the duct (i.e. near the umbilicus), it will give rise to a bright red, glistening polypoid nodule usually referred to as an umbilical polyp (Fig. 9.32). Meckel’s diverticulum, the most common anomaly of the omphalomesenteric duct, results from incomplete regression of the most proximal (enteric) portion.

Umbilical granuloma

Umbilical granulomas are small, red, broad-based, friable papules that develop if the umbilicus does not re-epithelialize completely; therefore they are not usually present at birth. They can be distinguished from umbilical polyps by the lack of serous, mucoid, or bloody discharge (Fig. 9.33), and their response to treatment with topical silver nitrate.

Prognosis and management

Umbilical granulomas can usually be treated with silver nitrate and are of little concern; however, these lesions may be difficult to clinically differentiate from congenital anomalies of the urachus and omphalomesenteric duct. In general, if the lesion is large, exophytic, and has a broad base (>0.5 cm), a referral to a pediatric general surgeon is indicated prior to treatment with silver nitrate.109

Amnion rupture malformation sequence/amniotic bands

A variety of disorders result from premature rupture of the amniotic sac. The clinical features will vary depending on the stage of development of the fetus at the time of rupture.110 The defects are thought to result from early rupture of the amniotic membrane, which subsequently results in failure of the amniotic sac to grow and the formation of fibrous strands from the outer surface of the amnion and the chorion. The fetus may become entangled in these strands if it passes through the defect. There may also be compression of the fetus secondary to oligohydramnios. Maternal trauma, dietary deficiencies, and teratogens have all been associated with amniotic rupture sequence.

Cutaneous findings

The most classic cutaneous finding is a constriction band of the distal extremity (Fig. 9.34). The band is usually circumferential and may be deep enough to cause lymphedema, compression of nerves, or even ischemia with resultant amputation.111 Aplasia cutis, irregular patches of alopecia, abnormal palmar creases, and alteration in dermatoglyphic pattern are also cutaneous features of the amnion rupture malformation syndrome.

Extracutaneous findings

Rupture early in gestation, during organogenesis, will lead to the most severe deformities. Severe craniofacial abnormalities, such as neural tube defects, and facial, chest, and abdominal wall clefts, have all been reported.

Treatment

Surgical correction is the only treatment option for these deformities and is often very challenging.112

Access the full reference list at ExpertConsult.com ![]()