CHAPTER 52 Development of the pectoral girdle and upper limb

STAGES OF UPPER LIMB DEVELOPMENT

At stage 16, the upper limb appears much more substantial. It is sometimes close to the body wall and sometimes abducted. The hand plate has the first indications of digit rays. By stage 17, the upper limb has an elbow region and digit rays; in advanced members of this stage, the hand plate has a crenated rim indicating the beginning of tissue removal between the digits (see Fig. 51.1). In stage 18 embryos (44 days), there is further crenation of the hand plate between the digit rays. Changes during stages 19–23 are concerned with growth of the limb and separation of the digits. The hands now curve over the cardiac region. The distal phalangeal portions of the fingers enlarge at stage 21, forming the nail beds.

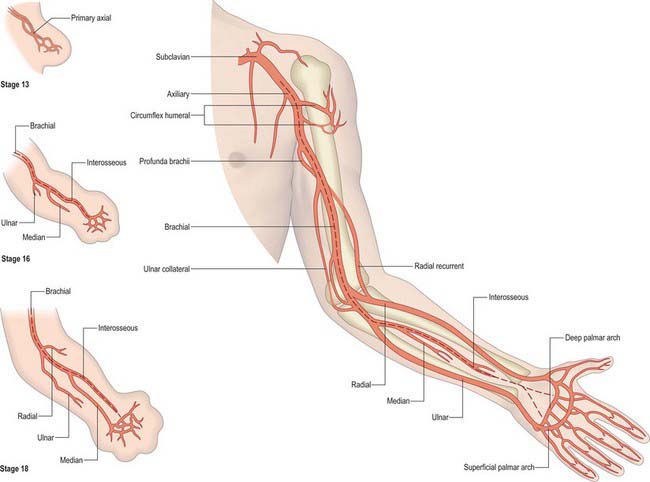

VESSELS IN THE UPPER LIMB

In the upper limb, usually only one arterial trunk, the subclavian, persists; it probably represents the lateral branch of the seventh intersegmental artery. Its main continuation (axis artery) to the upper limb (Fig. 52.1), later the axillary and brachial arteries, passes into the forearm deep to the flexor muscle mass and terminates as a deep plexus in the developing hand. The original axial vessel ultimately persists as the anterior interosseous artery and the deep palmar arch. A branch from the main trunk passes dorsally between the early radius and ulna as the posterior interosseous artery; a second branch accompanies the median nerve into the hand, where it ends in a superficial capillary plexus. The radial and ulnar arteries are the latest arteries to appear in the forearm. Initially the radial artery arises more proximally than the ulnar artery, crosses in front of the median nerve, and supplies biceps. Later, the radial artery establishes a new connection with the main trunk at or near the level of origin of the ulnar artery and the upper portion of its original stem usually disappears. On reaching the hand, the ulnar artery links up with the superficial palmar plexus, from which the superficial palmar arch is derived, while the median artery commonly loses its distal connections and is reduced to a small vessel. The radial artery passes to the dorsal surface of the hand; after giving off dorsal digital branches, it traverses the first intermetacarpal space and joins the deep palmar arch.

NEONATAL UPPER LIMB

In general, the upper limbs in the neonate are proportionately shorter than they are in the adult. They are long compared with the neonatal trunk and lower limbs, and extend to the upper thigh as they do in the adult, but the trunk is much shorter in the neonate (see Fig. 14.6). At birth, the upper limbs are about the same length as the lower limbs, but much more developed. When the proportions of parts of the upper limb are examined, the forearm is longer than the upper arm in the newborn, more so in boys than girls. Only primary centres of ossification are present in the upper limb, apart from a centre in the head of the humerus. The elbow of the newborn cannot achieve full extension, being some 10–15% short; it can flex to 145°. The neonate has a relatively strong grasp within the first few days. The fingernails of the upper limb usually extend to the finger tips or just beyond. They are soft at birth but soon dry and become quite firm and sharp.

UPPER LIMB ANOMALIES

A classification of congenital limb malformation uses seven subgroups (Swanson 1976). These describe a clinical picture and do not always relate accurately to the developmental process occurring in the limb. Failure of formation of parts of a limb is caused by developmental arrest affecting the long bones. The second subgroup, failure of differentiation, includes unsuccessful separation of parts, and so includes the range of syndactylies. Groups three to five include limb duplication, overgrowth and undergrowth. Group six includes limb amputations, mainly by adherent amniotic bands, and the last group includes all other generalized skeletal anomalies.