Chapter 11 Development of the head and neck, the eye and ear

Pharyngeal arches

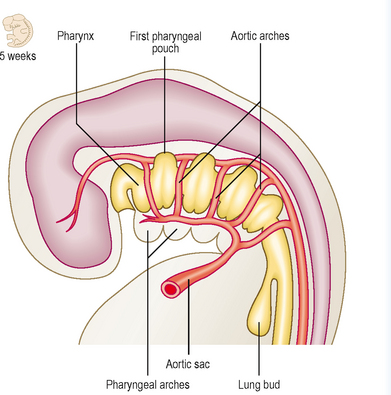

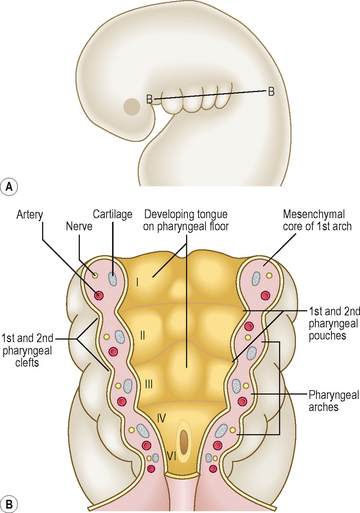

The pharyngeal arches begin to develop early in the fourth week from mesenchyme derived from the neural crest; the lateral plate mesoderm and the paraxial mesoderm also migrate to the head and neck region of the embryo. Five pairs of pharyngeal arches, numbered 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6, form in craniocaudal sequence and by the end of the fifth week, all pharyngeal arches appear as rounded swellings on the surface (Figs 11.1 and 11.2). The fifth pharyngeal arch is often rudimentary and soon disappears. Each pharyngeal arch consists of a core of mesenchyme, has an outer covering of ectoderm and is lined internally by endoderm. The ectoderm appears as the pharyngeal clefts (grooves) between the arches, and the endoderm as the pharyngeal pouches (Fig. 11.2B). The first pair of pharyngeal arches not only gives rise to the upper and lower jaw, but they also play a major role in the development of the face and palate.

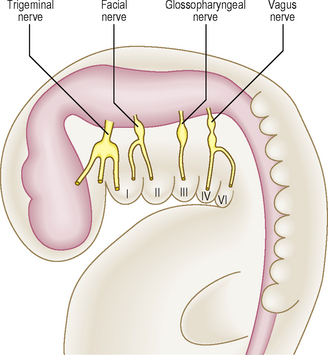

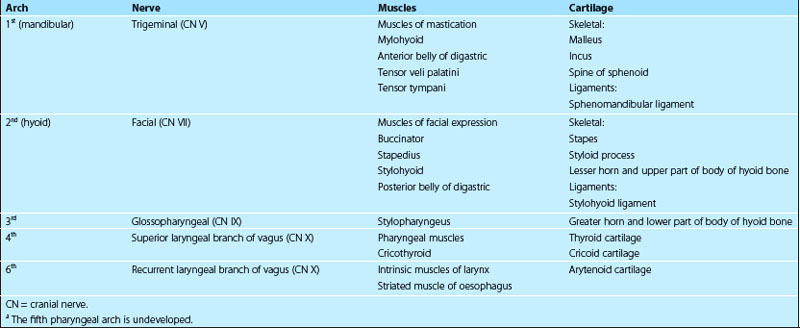

The mesenchyme in each pharyngeal arch differentiates into a bar of cartilage, the associated muscle and an aortic arch artery (Fig. 11.2B). Each pharyngeal arch also contains a cranial nerve (from nerves V, VII, IX and X) that enters it from the brainstem of the developing brain (Fig. 11.3). The cranial nerves carry the motor fibres to supply the muscles derived from the pharyngeal arches, and also carry the sensory fibres to the developing skin covering them and the mucosal tissue lining them. During further development many pharyngeal arch muscles migrate from their original site of origin to reach their final destination, but they retain their original innervation. Thus, the origin of each muscle can be determined from its nerve supply. The adult derivatives of pharyngeal arch structures, including the cartilages, the muscles and their appropriate cranial nerves, are summarized in Table 11.1. The derivatives of pharyngeal arch arteries are described in Chapter 6.

Pharyngeal clefts

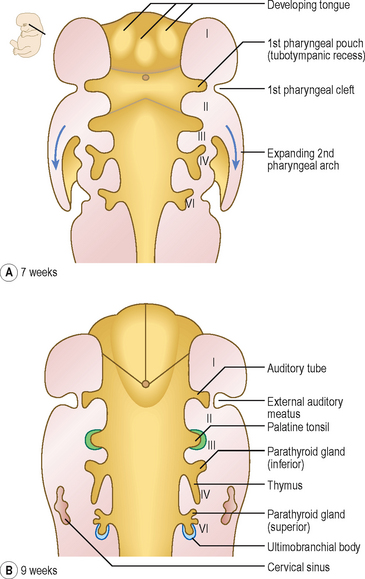

The four pharyngeal clefts separate the pharyngeal arches externally (Fig. 11.4). The first pair of pharyngeal clefts is the only one that contributes to adult structures, namely the external acoustic meatus. The second pharyngeal arch enlarges and grows rapidly as a flap over the remaining three pharyngeal clefts. This flap contains the platysma muscle and fuses below with the epicardial bulge covering the heart. It is possible that remnants of lower clefts lined with ectoderm may remain beneath the flap, forming a cervical sinus, but this is normally obliterated (Fig. 11.4B).

Pharyngeal pouches

The endoderm of the pharyngeal part of the foregut grows laterally as pockets on each side of the pharynx. These paired diverticula, the pharyngeal pouches, develop between the arches (Fig. 11.4A). The first pair of pouches, for example, lies in the interval between the first and second pharyngeal arches. The first four pouches are well developed; the fifth is often absent or rudimentary. The ends of the third and fourth pouches each form a dorsal and a ventral part. The first pouch expands into a tubotympanic recess; the tympanic (middle ear) cavity and auditory tube are derived from this recess (Fig. 11.4). The tympanic membrane is formed by the ectoderm of the first pharyngeal cleft, an intervening layer of mesenchyme and the endoderm lining the pouch. The derivatives of pharyngeal pouches are shown in Table 11.2 and Figure 11.4.

| Pharyngeal pouch | Main derivative |

|---|---|

| First | Tubotympanic recess, middle ear cavity, auditory tube and tubal tonsil |

| Second | Palatine tonsil (also pharyngeal and lingual tonsils) |

| Third |

Development of the tongue

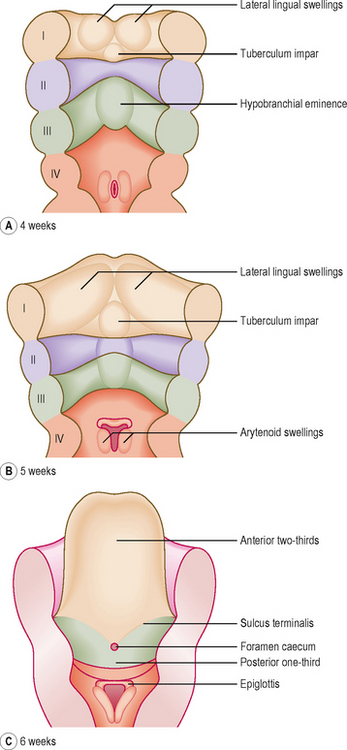

In the fourth week, the tongue develops from mesenchymal swellings covered with ectoderm and endoderm on the floor of the pharynx. The three swellings derived from the first arch mesenchyme, the lateral lingual swellings and a median tuberculum impar, merge with each other to form the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. The second pharyngeal arch makes no contribution to the tongue (Fig. 11.5A, B). Thus, the posterior one-third of the tongue comes from a single swelling, the hypobranchial eminence, derived from the third and fourth pharyngeal arches. A V-shaped groove, the sulcus terminalis, represents the line of fusion between the epithelium covering the first and third pharyngeal arches (Fig. 11.5C). A midline depression at the apex of the sulcus terminalis, the foramen caecum, marks the origin of the thyroid gland (see below).

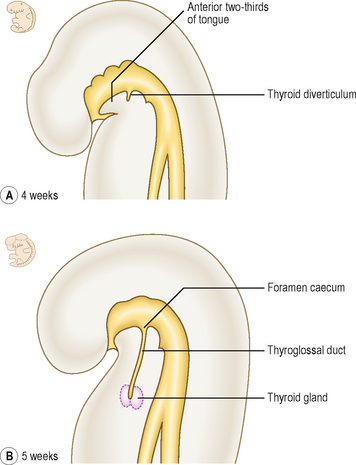

Development of the thyroid gland

The thyroid gland first appears in the fourth week as an invagination of the endoderm of the floor of the pharynx between the first and second pharyngeal pouches. This point of origin is seen in the adult as the foramen caecum. This soon grows as the thyroid diverticulum, descends in the neck and divides into right and left lobes, connected by an isthmus (Fig. 11.6). The lengthening tube of epithelium between the foramen caecum and the gland is called the thyroglossal duct. The thyroid gland becomes detached from the pharyngeal floor when the thyroglossal duct regresses. The lower end of the thyroglossal duct may give rise to a pyramidal lobe at the isthmus of the gland, or some smooth muscle, the levator glandulae thyroideae.

Development of the face

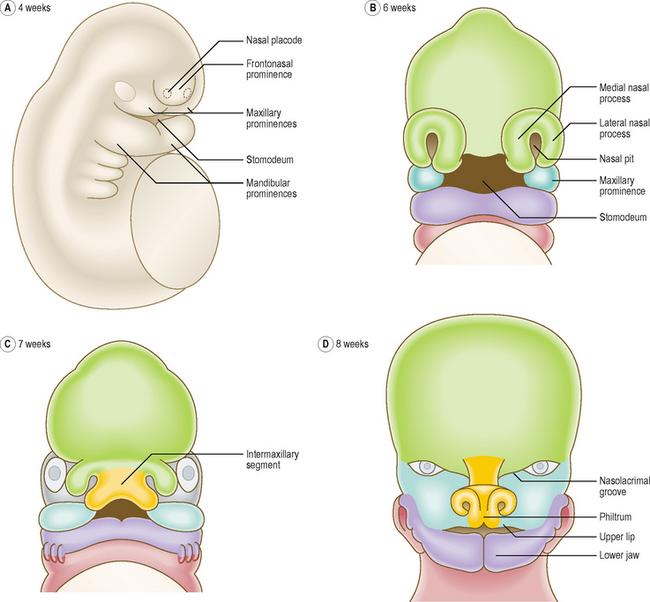

The face begins to form during the fourth week when the neural crest mesenchyme surrounding the opening of the stomodaeum produces five prominences or swellings. These facial prominences consist of a single frontonasal prominence, paired maxillary prominences and paired mandibular prominences (Fig. 11.7A). Table 11.3 shows the structures derived from the three facial primordia.

Table 11.3 Main structures derived from the facial prominences

| Prominence | Main structures |

|---|---|

| Frontonasal prominence | Forehead, nose, philtrum, primary palate |

| Maxillary prominences | Part of the cheek, maxilla, zygoma, lateral portion of upper lip, secondary (hard and soft) palate |

| Mandibular prominences | Lower lip, part of the cheek, mandible |

During the fifth week, two events shape the facial appearance: maxillary prominences enlarge and grow in the medial direction, and bilateral ectodermal thickenings, the nasal placodes, appear on the frontonasal prominence. The mesenchyme around each nasal placode forms the medial and lateral nasal processes (Fig. 11.7A, B). The medial nasal processes move towards each other, merge in the midline, and form an intermaxillary segment (Fig. 11.7C). The maxillary prominences fuse with the lateral nasal process and then with the medial nasal processes to form the upper lip. Each maxillary prominence is separated from the lateral nasal process by a nasolacrimal groove (Fig. 11.7D). The ectoderm at the floor of this groove canalizes to form the nasolacrimal duct; its upper end expands to form the lacrimal sac. The maxillary and mandibular prominences merge laterally to form the cheeks and their fusion determines the width of the mouth. The lower jaw is formed when the mandibular prominences merge in the midline (Fig. 11.7D).

Development of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses

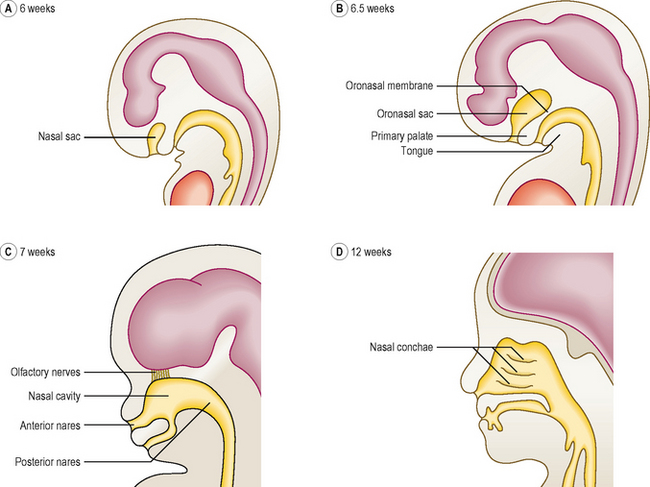

During the development of the face, the nasal placodes invaginate to form the nasal pits (see Fig. 11.7B). As a result of the enlargement of the medial and lateral nasal processes on both sides of the nasal pits, the pits deepen and become nasal sacs (Fig. 11.8A, B). The nasal sacs grow upwards and are separated from the oral cavity by the oronasal membrane, which breaks down during the seventh week to bring the nasal cavities into communication with the oral cavities (Fig. 11.8C). After the formation of the palate, these openings, the posterior nares, open into the pharynx. The nasal pits open on the face as the nostrils or anterior nares.

During the ninth week, the nasal septum develops from the fused medial nasal processes and grows downwards to fuse with the palate. Meanwhile, the superior, middle and inferior conchae form as shelves on the lateral wall of the nasal cavity (Fig. 11.8D). Late in fetal life the maxillary sinuses grow as diverticula from the lateral wall of the nasal cavities into the maxillae bones. The remainder of the paranasal sinuses develop after birth, and their postnatal growth has a significant impact on the shape and size of the face during early childhood and puberty.

Formation of the palate

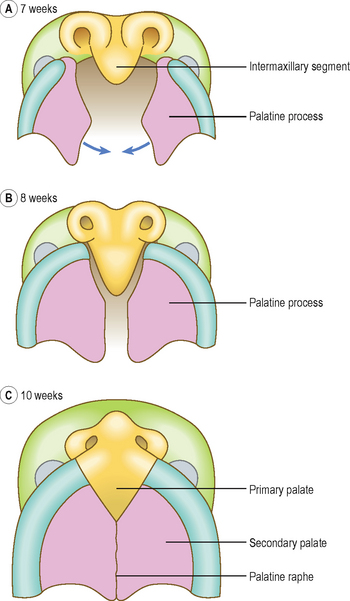

The palate develops from fusion of the primary and secondary palate (Fig. 11.9C). The primary palate is derived from the intermaxillary segment and the secondary palate formed by two palatine processes or palatal shelves from the maxillary prominences.

Initially each palatine process grows obliquely downwards on each side of the tongue. At the end of the ninth week, the palatine processes elevate rapidly to a horizontal position above the tongue. After they have elevated they then fuse with the primary palate and then with each other from anterior to posterior, joining in the midline (Fig. 11.9A, B) at the palatine raphe. At the same time, the frontonasal process and the medial nasal processes form the nasal septum; the latter grows down to meet the upper surface of the palate.

Development of the eye and ear

Ectodermal placodes

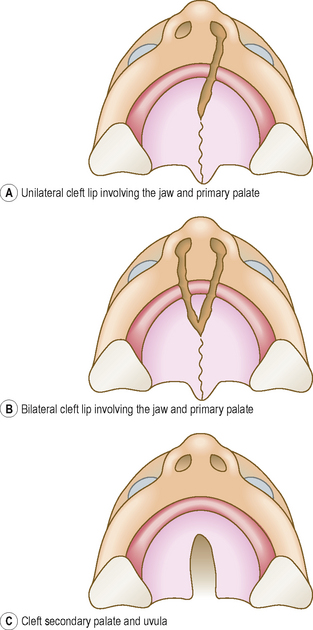

Cleft lip and cleft palate are common defects that result in abnormal facial appearance, defective speech and trouble with feeding. The cleft palate results when the two palatal shelves fail to meet and fuse with each other. There are two major groups of cleft lip and palate, anterior and posterior deformities, with the incisive foramen as the dividing landmark. The anterior deformities include cleft lip, with or without cleft upper jaw, and cleft between the primary and secondary palates (Fig. 11.10A, B). Those that lie posterior to the incisive foramen include cleft secondary palate and cleft uvula (Fig. 11.10C).

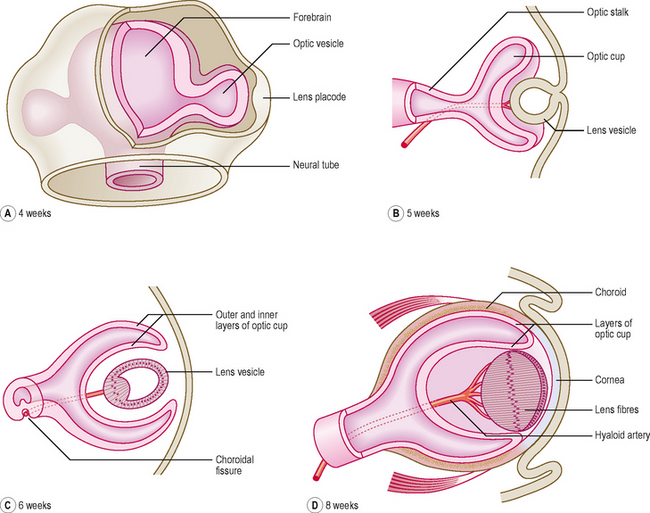

The eye

The earliest indication of the eye is in the form of the optic vesicle, which develops at the beginning of the fourth week as an outgrowth from the lateral wall of the forebrain. The optic vesicle acts on the surface ectoderm to induce the development of the lens placode (Fig. 11.11A). Simultaneously, the connection between the optic vesicle and the brain narrows to form the optic stalk. The lens placode invaginates to form the lens vesicle, which soon detaches from the surface ectoderm and sinks into the optic vesicle (Fig. 11.11A). The optic vesicle is now indented to become a double-walled optic cup (Fig. 11.11B, C). Grooves appear on the ventral surface of the optic cup and along the optic stalk forming the choroidal fissure. A branch of the ophthalmic artery, the hyaloid artery, passes along the choroidal fissure to supply the lens and the developing retina. Soon the edges of the choroidal fissure fuse, thus enclosing the hyaloid artery and its accompanying vein in a canal. The proximal part of the hyaloid artery persists as the central artery of the retina.

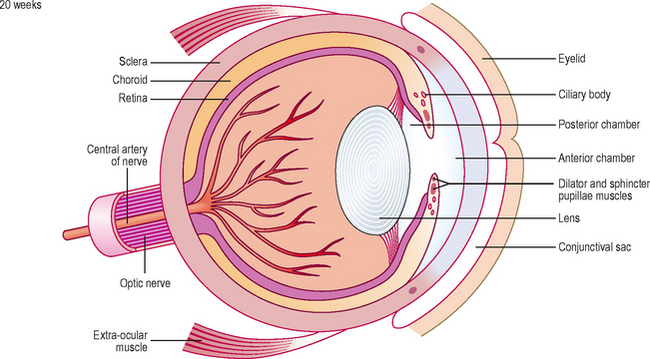

The retina is formed by the two layers of the optic cup, the outer layer forms the pigmented layer of the retina, and the inner or neural layer proliferates to form the rods and cones, and the cell bodies of neurons. The neurons differentiate into bipolar cells, ganglionic cells and neuroglial cells. The axons of the ganglionic cells line the inner surface of the retina and form the optic nerve. At the rim of the optic cup, both layers of the retina give rise to the iris and ciliary body. The neurectoderm overlying the iris forms the connective tissue and the dilator and sphincter pupillae muscles.

The lens is initially a hollow structure. However, soon the posterior cells of the lens vesicle elongate to form the lens fibres; these arrange in a laminar pattern to produce a transparent lens (Fig. 11.11C). The mesenchyme around the optic cup condenses to form the layers of the eyeball, the inner vascular choroid and the outer fibrous sclera. The most anterior part of the cornea becomes transparent (Fig. 11.11D). The spaces that develop in the mesenchyme between the cornea and the lens accumulate secretions from the ciliary body, and enlarge to form the anterior chamber of the eye (Fig. 11.12). A delicate meshwork of fibrous tissue with a gelatinous substance fills the gap between the lens and the retina, thus forming the vitreous body, which occupies the posterior chamber.

The eyelids develop as folds of ectoderm with mesenchyme between them that grow over the cornea. As the two eyelids grow towards each together, they fuse to enclose a conjunctival sac anterior to the cornea (Fig. 11.12). The inner layer of the ectoderm becomes the conjunctiva and over the iris it fuses with the cornea. The lacrimal glands form as ectodermal buds from the upper part of the conjunctival sac into the surrounding mesenchyme. The eyelids become separated again by the fifth to seventh months in utero.

The ear

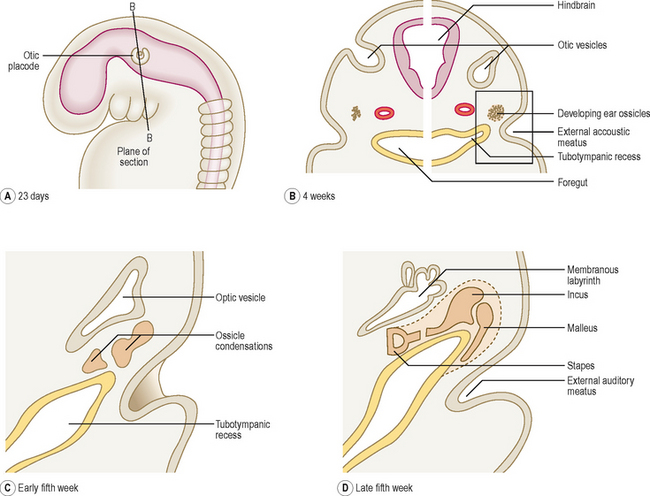

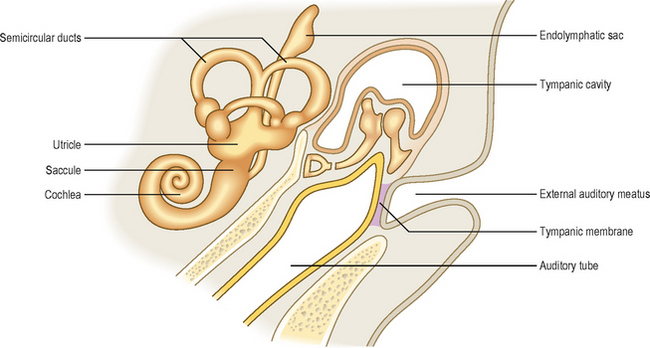

The three anatomical subdivisions of the ear have a dual origin. The external and middle ears are derived from the first two pharyngeal arches and from the intervening pharyngeal cleft and pouch. The formation of the external and middle ears is described earlier in this chapter. The inner ear arises from an ectodermal placode that develops at the level of the hindbrain.

The inner ear is first to develop (at about 22 days) as the otic placode, close to the hindbrain (Fig. 11.13A). It invaginates as the otic vesicle and soon separates from the surface ectoderm (Fig. 11.13B). The optic vesicle enlarges, modifies its shape, forming a dorsal vestibular portion (from which the semicircular canals arise) and a ventral cochlear portion (from which the cochlea arises). A diverticulum arises from the otic vesicle to form the endolymphatic sac (Fig. 11.14). The vestibular portion develops two sacs, an expanded larger utricle and a smaller saccule. Three tubes grow from the utricle to give rise to the semicircular ducts. The lower part of the saccule elongates and spirals as the cochlea. These structures derived from the otic vesicle constitute the membranous labyrinth (Fig. 11.13D). The mesenchyme around the membranous labyrinth becomes the cartilaginous otic capsule; later this is ossified to form the bony labyrinth of the inner ear. The cavities that appear in the otic capsule merge to form a perilymphatic space, which develops the two adult subdivisions, the scala tympani and the scala vestibuli.

Five pairs of mesenchymal pharyngeal arches, ectodermal pharyngeal clefts and endodermal pharyngeal pouches develop on either side of the pharyngeal gut.

Five pairs of mesenchymal pharyngeal arches, ectodermal pharyngeal clefts and endodermal pharyngeal pouches develop on either side of the pharyngeal gut. The face is formed by the fusion of five facial prominences around the opening of the mouth and the palate from the fusion of an unpaired intermaxillary process and two palatine shelves.

The face is formed by the fusion of five facial prominences around the opening of the mouth and the palate from the fusion of an unpaired intermaxillary process and two palatine shelves.

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box