CHAPTER 38 Development of the ear

INNER EAR

The production of a precisely positioned and functionally well tuned inner ear depends on genetic patterning and a cascade of transcription signals expressed by numerous tissues, including the developing inner ear and its surrounding periotic mesenchyme, the adjacent hindbrain, neural crest and notochord (e.g. Liu et al 2003).

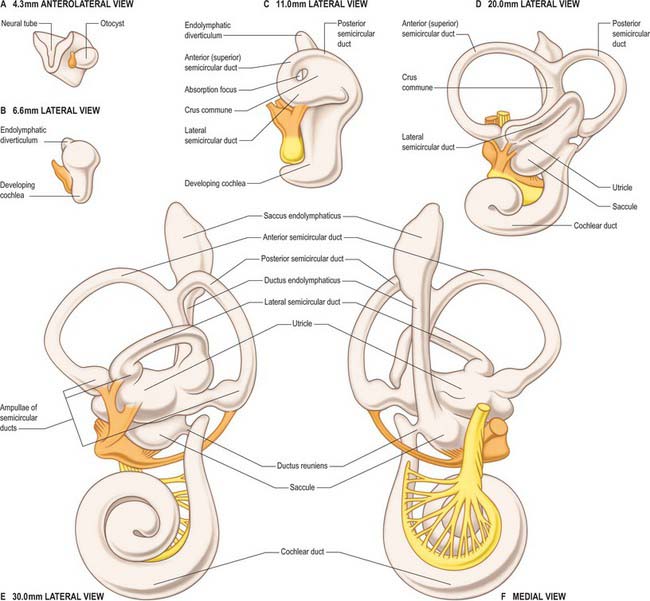

The first signs of inner ear development are visible shortly after those associated with the developing eyes. Two patches of ectodermal thickening, the otic placodes, appear lateral to the hindbrain at stage 9. Each otic placode invaginates as an otic pit, adjacent to rhombomeres 5 and 6 of the hindbrain and dorsal to the second pharyngeal cleft. The pit becomes pinched off from the surface ectoderm to form a simple epithelial sac, the otocyst (auditory or otic vesicle), during stage 12 (Fig. 38.1).

The first morphological differentiation of the otic vesicle is visible during stage 14 (approximately 33 days) and presages the three major subdivisions of the inner ear, i.e. the endolymphatic sac and duct, the dorsal utricular portion that later gives rise to the semicircular canals, and the ventral saccular portion that later gives rise to the cochlea. At this time the otocyst is piriform in shape. A tubular diverticulum develops from its medial rim and differentiates into the endolymphatic duct and sac. The sac communicates via the endolymphatic duct with the remainder of the otocyst which is placed laterally and can be regarded as the utriculosaccular chamber. At the same time, two plate-like diverticulae, one vertical and one horizontal, emerge from the dorsal part of the utriculosaccular chamber. The opposing epithelia in the central region of each outgrowth coalesce to form a fusion plate, and the central part of this plate is eventually resorbed, producing a tubular canal. The vertical plate gives rise to the anterior and posterior semicircular canals that share a common crural attachment to the utriculosaccular chamber, and the horizontal plate gives rise to the horizontal or lateral semicircular canal. A medially directed evagination, the cochlear anlagen, is evident in the ventral part of the utriculosaccular chamber in a 7–9 mm (approximately 35 days) embryo. The proximal region of the cochlear duct continues to increase in length and its distal region becomes progressively more coiled. When the duct has achieved its final length and spiral configuration, its proximal part becomes constricted, forming the ductus reuniens.

MIDDLE EAR (TYMPANIC CAVITY) AND PHARYNGOTYMPANIC (AUDITORY) TUBE

All the components of the outer and middle ears develop from the first and second pharyngeal arches. The pharyngotympanic tube and tympanic cavity are lateral extensions of the early pharynx (see Fig. 35.4). They become visible in a 4–6 mm (approximately 28 days) embryo as a hollow, the tubotympanic recess, lying between the first and second pharyngeal arches, with a floor which consists of the second arch and its limiting pouches. The forward growth of the third pharyngeal arch causes the proximal part of the recess to remain narrow, forming the pharyngotympanic tube region, and also excludes the inner part of the second arch from this portion of the floor. The more lateral part of the recess eventually comes in contact with the first pharyngeal cleft and widens and develops into the tympanic cavity; its floor later forms the lateral wall of the tympanic cavity up to approximately the level at which the chorda tympani branches off from the facial nerve. The lateral wall of the tympanic cavity contains first and second arch elements. The first arch territory is limited to that part in front of the anterior process of the malleus, and the second arch forms the outer wall behind this and also turns on to the posterior wall to include the tympanohyal region.

The middle ear ossicles are of neural crest origin, i.e. crest cells that have migrated from rhombomeres 1–4 into the mesenchyme of the first and second pharyngeal arches. The malleus develops from the dorsal end of the ventral mandibular (Meckel’s) cartilage of the first arch. The incus develops from the dorsal cartilage of the first arch which is probably homologous to the quadrate bone of birds and reptiles. The origin of the stapes in humans remains controversial. It is thought to be derived mainly from an anlage situated in the cranial end of the cartilage of the second pharyngeal arch, initially as a ring (anulus stapes) that encircles the small stapedial artery (for a recent analysis of the development of the stapes, consult Rodriguez-Vazquez 2005). The primordium of the stapedius muscle appears close to the artery and facial nerve in a 13–17 mm (approximately 48 days) embryo, and tensor tympani starts to appear near the extremity of the tubotympanic recess at almost the same time. At first the ossicles are embedded in the mesenchymal roof of the tympanic cavity, later they become covered by the mucosa of the middle ear as the tympanic cavity fills with air after birth. Further postnatal developmental changes contribute to the functional maturation of the middle ear.

EXTERNAL EAR

The external acoustic meatus develops from the dorsal end of the first pharyngeal (hyomandibular) cleft (see Fig. 35.4). Close to its dorsal extremity this groove extends inwards as a funnel-shaped primary meatus from which the entire cartilaginous part of the meatus, and a small area of its roof, are developed. A solid epidermal plug extends inwards from the tube along the floor of the tubotympanic recess. The cells in the centre of the plug subsequently degenerate to produce the inner part of the meatus (secondary meatus). The epidermal stratum of the tympanic membrane is formed from the deepest ectodermal cells of the epidermal plug, and the fibrous stratum is formed from the mesenchyme between the meatal plate and the endodermal floor of the tubotympanic recess.

The development of the auricle is initiated by the appearance of six tissue elevations, the auricular hillocks, which form round the margins of the dorsal portion of the first pharyngeal cleft. Of the six, three are on the caudal edge of the first pharyngeal (mandibular) arch and three on the cranial edge of the second pharyngeal (hyoid) arch. The hillocks appear from stage 15; before then, only the most ventral hillock on the mandibular arch, which subsequently forms the tragus, can be identified. The rest of the auricle is formed in the mesenchyme of the hyoid arch which extends forwards round the dorsal end of the remains of the first pharyngeal cleft, forming a keel-like elevation which is the forerunner of the helix. The contribution made by the mandibular arch to the auricle is greatest at the end of the second month, thereafter this contribution becomes relatively reduced as growth continues, until eventually the area of skin supplied by the mandibular nerve extends little above the tragus. The lobule is the last part of the auricle to develop.

Common congenital deformities of the auricle are described in Chapter 36.

Liu W, Oh SH, Kang Yk Y, Li G, Doan TM, Little M, Li L, Ahn K, Crenshaw EB, Frenz DA. Bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4): a regulator of capsule chondrogenesis in the developing mouse inner ear. Develop Dynamics. 2003;226:427-438.

Rodriguez-Vazquez JF. Development of the stapes and associated structures in human embryos. J Anat. 2005;207:165-173.