Chapter 299 Development and Developmental Anomalies of the Teeth

Calcification

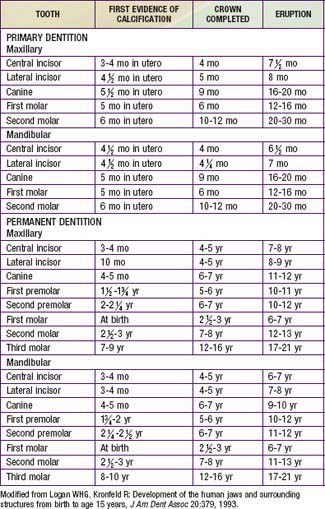

After the organic matrix has been laid down, the deposition of the inorganic mineral crystals takes place from several sites of calcification that later coalesce. The characteristics of the inorganic portions of a tooth can be altered by disturbances in formation of the matrix, decreased availability of minerals, or the incorporation of foreign materials. Such disturbances can affect the color, texture, or thickness of the tooth surface. Calcification of primary teeth begins at 3-4 mo in utero and concludes postnatally at ∼12 mo with mineralization of the 2nd primary molars (Table 299-1).

Eruption

At the time of tooth bud formation, each tooth begins a continuous movement toward the oral cavity. The times of eruption of the primary and permanent teeth are listed in Table 299-1.

Anomalies Associated with Tooth Development

If the dental lamina produces more than the normal number of buds, supernumerary teeth occur, most often in the area between the maxillary central incisors. Because they tend to disrupt the position and eruption of the adjacent normal teeth, their identification by radiographic examination is important. Supernumerary teeth also occur with cleidocranial dysplasia (Chapter 303) and in the area of cleft palates.

Amelogenesis imperfecta represents a group of hereditary conditions that manifest in enamel defects of the primary and permanent teeth without evidence of systemic disorders (Fig. 299-1). The teeth are covered by only a thin layer of abnormally formed enamel through which the yellow underlying dentin is seen. The primary teeth are generally affected more than the permanent teeth. Susceptibility to caries is low, but the enamel is subject to destruction from abrasion. Complete coverage of the crown may be indicated for dentin protection, to reduce tooth sensitivity, and for improved appearance.

Dentinogenesis imperfecta, or hereditary opalescent dentin, is a condition analogous to amelogenesis imperfecta in which the odontoblasts fail to differentiate normally, resulting in poorly calcified dentin (Fig. 299-2). This autosomal dominant disorder can also occur in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. The enamel-dentin junction is altered, causing enamel to break away. The exposed dentin is then susceptible to abrasion, in some cases worn to the gingiva. The teeth are opaque and pearly, and the pulp chambers are generally obliterated by calcification. Both primary and permanent teeth are usually involved. If there is excessive wear of the teeth, selected complete coverage of the teeth may be indicated to prevent further tooth loss and improve appearance.