chapter 14 Detoxification

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

Toxins are ubiquitous in modern life, from the air we breathe to the food we eat. Today’s lifestyles and the increase in environmental pollutants have significantly increased the average person’s exposure to toxins,1 and this is placing new demands on natural detoxification mechanisms and causing an accumulation of toxins in our bodies.2

Detoxification is garnering more public recognition and many critics have dismissed ‘detox’ as a popular buzz term, promising a cure-all for better health and vitality but failing to deliver.3 It is true that many detoxification treatments lack efficacy, and certain protocols such as water fasting are rightfully criticised as detrimental to human health.2,3

However, as we become increasingly aware of the effects of pollution and globalisation on human health, it is important to consider the full spectrum of possible causes of illness and the damaging role toxins play in disease. While more clinical-based research is needed in this area, there is growing evidence that toxicity plays a major role in disease and must be addressed. Healthcare professionals are considering the importance of supporting the body’s natural detoxification mechanisms and identifying effective techniques to achieve this.4

WHAT ARE TOXINS?

The US Environmental Protection Agency recognises the existence of over 4 million toxic compounds,5 which can be categorised as follows:

Most toxins concentrate in adipose tissue and accumulate during a lifetime, leading to increasing toxic loads with age.7 Often, toxins are also transferred through the umbilical cord, paternal DNA and breast milk, and may even affect gene expression in the unborn child, passing the burden on to future generations.8–10

THE EFFECTS OF TOXINS

Toxins contribute to a wide range of diseases and pathological conditions. The effects of toxins are wide-reaching, and studies have identified direct relationships between toxic compounds and disorders of the nervous, endocrine and immune systems.1,11–13 This may help to explain the aetiology and increasing prevalence of diseases such as ADHD, asthma and allergies, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), chronic fatigue syndrome, depression, reproductive disorders, diabetes and cancer.

NEUROLOGICAL

Neurological illnesses including Parkinson’s disease, ADHD and Alzheimer’s disease have been linked to toxins,1,14,15 possibly due to the omnipresence of major neurotoxic pesticides that are readily available—from the local grocery produce to commonly used backyard herbicides.1

Interestingly, farmed Atlantic salmon, once considered ‘brain-health food’, has been found to contain high levels of methylmercury and PCBs, which can lead to neuronal decline, necrosis and demyelination if consumed over many years.16 Additionally, chemotherapeutic drugs such as doxorubicin and cisplatin have also been shown to cause direct damage to the nervous system.1

Recent studies have found additives in processed and convenience foods that can trigger mild thyrotoxicosis and dopamine deficiency, and this may play a role in explaining why so many of today’s children are affected by attention deficits and other mental disorders.15,17

IMMUNE

Some toxic compounds can lower the body’s immunity and increase the likelihood of infection and cancer. Others are known to promote inflammation and are strongly linked to common allergic reactions.13,18,19

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that there is growing evidence that a vast number of environmental agents and therapeutics cause autoimmune-like diseases. For example, while the underlying aetiology of SLE is unknown, research points towards possible adverse reactions to toxic chemicals including pharmaceutical drugs such as hydralazine, isoniazid and minocycline.1,20,21

ENDOCRINE

Many environmental chemicals are xeno-oestrogens or endocrine disruptors that can affect the endocrine system. Known hormone disruptors, such as the plasticisers (phthalates and bisphenol-A), are readily found in the environment and common goods such as children’s toys and baby bottles, plastic food wrap, cosmetics and tinned food cans. This may help explain the rise in premature puberty among girls.22 These common plasticisers and other environmental chemicals have been shown to lower progesterone, which may contribute to PMS symptoms, breast cysts, miscarriages and even breast cancer.6,23–25 Additionally, atrazine, the most commonly used herbicide in America’s agriculture industry, is also a xeno-oestrogen and is strongly linked to breast, uterine and ovarian cancers.26,27 Many harsh toxic chemicals can also cross the placenta and are passed on to children in utero and through breast milk.6,8

Male fertility has also not escaped the effects of environmental toxins. Since the 1940s, there has been a drop in sperm count, with an overall reduction of 50%.28,29 Toxins such as PCBs have also had ‘gender-bender’ effects, reversing the sex of male turtle eggs.30

In addition to affecting reproductive tissues, toxins take their toll on the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis, influencing sleep patterns, mood, libido and energy levels.1 Solvents found in petrol, glue and fabric cleansers cause destruction of the adrenal glands and disrupt cortisol production.16,31

If liver or gut function is compromised due to a nutrient deficiency, toxic stress or imbalances in gut flora, endogenous hormones such as oestradiol and its metabolites may accumulate in the body, causing oestrogen dominance and increasing the risk of breast and ovarian cancer.6

BODY WEIGHT

Toxins accumulate in adipose tissue and lead to difficulties in losing weight. Studies have shown that the heavy metals and industrial chemicals such as those found in car exhaust fumes concentrate in cellular mitochondria.32 These toxins infiltrate the mitochondria and alter the cells’ normal biochemistry and energy production, resulting in reduced lipolysis, thermogenesis and ATP production. Thus, toxic exposure will reduce fat breakdown, basal metabolic rate and energy production.32

DIABETES

Based on current research, a new school of thought is emerging on the aetiology of diabetes. As scientific research in this field evolves, scientists are beginning to see a link between diabetes and the level of toxins stored in the body. For example, people with the highest level of stored toxins (such as those found in dry cleaning and lindane shampoo) are almost 40 times more likely to have diabetes.33 The Lancet has gone as far as to say that obesity is a major contributor to type 2 diabetes primarily because fat is a vehicle for persistent organic pollutants.34

CANCER

There is increasing evidence to suggest that toxicity is a major contributor to cancer incidence. The Journal of the American Medical Association holds that even once smoking is factored out, the rates of cancer are higher for those born after 1940 and can partly be attributed to an increased exposure to environmental carcinogens.35 The British Medical Journal further vindicates this theory in saying that, ‘Environmental and lifestyle factors are key determinants of human disease—accounting for perhaps 75 per cent of most cancers’.36

The mechanisms of action to explain the carcinogenic effects of toxins of course include potential direct mutagenic effects on cells. Other indirect mechanisms have been postulated. Heavy metals, pesticides and drugs such as cimetidine are known disruptors of mitochondrial function, increasing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).37 In turn, the ROS activate inflammatory transcription factors and cause oxidative damage to nuclear DNA, leading to mutations and carcinogenesis.38,39

Breast adipose tissue is found to concentrate organochlorine compounds (OCCs) more than other bodily adipose cells and has been found in higher concentrations in women with breast cancer.40–42 Another study found a fourfold increased risk of breast cancer associated with raised serum PCB and DDE.43 However, other studies have failed to observe an increased risk.44,45

Exposure to environmental toxins is also implicated in the development of other adult and childhood cancers, particularly haematological and brain.46–50

CARDIORESPIRATORY

The APHENA (Air Pollution And Health: A Combined European And North American Approach) study combines health data and air pollution monitoring from cities across Europe, the United States and Canada. The results confirm earlier findings of an increased all-cause mortality associated with air pollution, especially particulate matter with a diameter less than 10 nm. Elderly and unemployed people were more at risk, as were Canadians.51

Other epidemiological studies have also found an association with daily fluctuations in particulate matter as well as sulfur- and nitrogen-based air pollutants. Air pollution is positively associated with school absenteeism, reduced peak flow rates in normal children and acute cardio and respiratory admissions to hospital, and mortality.52 Long-term exposures of over 3 years may even increase these risks.53 Furthermore, there appears to be no safe lower limit where the rates of illness plateau. The levels set for public health pollution alerts are therefore arbitrary.

Increased rates of asthma and chronic bronchitis, especially in children, have been observed with higher indoor air levels of solvents and formaldehyde.54

DETOXIFICATION: HOW THE BODY PROCESSES TOXINS

GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

Over the course of a lifetime, the gastrointestinal tract processes more than 25 tons of food, which represents the largest load of antigens and xenobiotics confronting the human body.55

As many toxins are stored in adipose tissue, the best way to eliminate toxic load is to increase the amount of fat excreted in the stool.32 In the small intestine, toxins from food and bile are mixed with pancreatic enzymes that emulsify fat for absorption. Importantly, this leads to an increase in the absorption of toxins.

Gastrointestinal flora are important for the proper elimination of toxins, especially hormone metabolites. For example, after being metabolised by the liver, conjugated oestrogens are eliminated through the bowels. Gut dysbiosis with pathogenic bacteria can produce deconjugating enzymes such as beta-glucuronidase that cleave oestrogen metabolites from their neutralising conjugates. The metabolites are reabsorbed via the enterohepatic circulation.56

LIVER

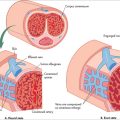

The liver is the main organ for detoxifying lipophilic chemicals, filtering about one litre of blood per minute.6 The rate of detoxification is a function of hepatic blood flow and liver enzyme activity. The detoxification pathways can be divided into two main phases. Most chemicals are first activated through phase 1 before being conjugated in phase 2. However, some chemicals bypass phase 1 and are simply conjugated for renal or biliary excretion.

Phase 1 detoxification

Phase 1 pathways include the flavine-containing monooxygenases (FMO) (NADPH-dependent oxidation), alcohol dehydrogenase and the famous cytochrome P-450 superfamily of enzymes, which metabolise thousands of exogenous and endogenous compounds and are responsible for the activation and detoxification of over 90% of pharmaceuticals. The majority of phase 1 metabolites are reactive, highly volatile substances and require phase 2 for neutralisation. These reactive intermediates are up to 60 times more toxic than their parent molecules and can act as free radicals in the body, capable of causing significant oxidative damage, inflammation, DNA mutations and cancer.57 For example, paracetomol-associated hepatotoxicity does not result from the drug itself but from depleted hepatic glutathione stores (an important hepatic antioxidant) and accumulation of a hepatotoxic phase 1 metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine.58

KIDNEYS

The kidneys are the primary organs for excretion of water-soluble endogenous and exogenous toxins. Smaller-sized toxins unbound to plasma proteins filter through the glomeruli, which act like a sieve. Other toxins, including metals and drugs, urea and uric acid, are passively and actively excreted via tubule secretion. The ionisation of weak organic acids and bases in the tubules is also used to excrete many toxins, especially drugs.59 As well as increasing the reabsorption of water, antidiuretic hormone (ADH) increases the reabsorption of urea and reduces urine flow and thus the clearance of toxins.59

OTHER PATHWAYS OF DETOXIFICATION

As the largest organ in the body, the skin can eliminate heavy metals and chemical xenobiotics through perspiration.60 Furthermore, when other organs of elimination such as the kidneys are failing, the skin aids in the elimination process, as is seen in uraemic frost.

Toxins may also be eliminated through breast milk and exhaled air.

ASSESSMENT OF TOXICITY AND DETOXIFICATION

ASSESSMENT FOR A DETOXIFICATION PROGRAM

The assessment of the patient should begin with a thorough case history to evaluate exposure to toxins (Box 14.1) and the potential impact on the patient’s health (Boxes 14.2 and 14.3). For each exposure, the patient should be asked about any health complaints experienced at the time or shortly after exposure as well as any potential sequelae. It is also important to appreciate that due to genetic variability, some patients are more affected by toxic chemicals than others. It is therefore vital to assess each patient on an individual basis and to not discount even small amounts of exposure.

LABORATORY TESTING

DETOXIFICATION PROTOCOLS

Today’s practitioners administer a wide variety of detoxification protocols. It is worth noting, however, that few are evidence-based and that they are supported by limited clinical research. A recent clinical trial that used traditional ayurvedic methods had promising results, with its ability to reduce PCBs and beta-HCH levels.63 Consequently, rather than presenting a protocol, we will present the main elements often prescribed in detoxification therapy.

GUIDELINES FOR REDUCING TOXIN EXPOSURE

DIET PLAN AND SUPPLEMENTS TO SUPPORT DETOXIFICATION

Methods to support gastrointestinal elimination of toxins include:

LIVER DETOXIFICATION

Many studies suggest that a lack of balance between the two liver detoxification phases can increase the risks of drug reactions and oxidative stress, as well as contributing to the aetiology of chronic diseases such as cancer, Parkinson’s disease and systemic lupus erythematosus.74–78 As such, practitioners aim to achieve a balance between the two phases, to reduce the accumulation of both unprocessed toxins and reactive intermediate metabolites.65,79

Liver detoxification is influenced by herbal and nutritional supplements, along with diet. These can be used to help create optimal liver detoxification (Table 14.1). It is important to ensure adequate intake of antioxidants to protect the body from any free-radical formation caused by the accumulation of the reactive intermediates formed by phase 1.

| Phase 1 | |

| Vitamins | Riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), pyridoxine (B6), B12 |

| Herbs | Schizandra, St John’s wort, rosemary, green tea, curcumin |

| Other | Glutathione, branched chain amino acids, flavonoids, phospholipids |

| Antioxidant vitamins & minerals | Carotenes (vitamin A), ascorbic acid (vitamin C), tocopherols (vitamin E), selenium, copper, zinc, manganese, coenzyme Q10, bioflavonoids |

| Phase 2 | |

| Amino acids | Cysteine, glutathione, L-glycine, L-glutamine, taurine, methylation cofactors |

| Vitamins | Thiamin (B1), riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), pyridoxine (B6), B12, folic acid |

| Herbs | Milk thistle |

| Other micronutrients | Indole-3-carbinol, found in Brassica vegetables |

KIDNEY DETOX

Increasing hydration is the simplest method of enhancing the kidneys’ elimination of toxins. As well as increasing glomerular filtration and urine flow, a high water intake reduces ADH secretion and its consequent reabsorption of urea92 and other water-soluble toxins.59 The consumption of 2–3 litres per day of filtered water for an average-sized adult is recommended during a detoxification program. Herbs and foods traditionally used for their diuretic properties, such as dandelion, nettle, parsley, watermelon and asparagus, may also be used.6

SKIN, LYMPHATIC AND CIRCULATORY STIMULANTS

OTHER INTERVENTIONS TO AUGMENT DETOXIFICATION

HEAVY METALS DETOXIFICATION

Chelation therapy is used for treating acute heavy metal poisoning. Common chelating agents include 2,3-dimercapto-1-propane sulfonic acid (DMPS), meso-2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid isomer (DMSA), D-penicillamine, British antilewisite (BAL) and ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA). However, the use of chelating agents for the removal of stored heavy metals from low-level chronic exposure is controversial. Advocates for the wider use of chelation therapy use chelators such as EDTA for a range of conditions from metal toxicity to cardiovascular disease, macular degeneration and cancer.97–99 While chelation therapy may be an effective method for treating heavy metal poisoning such as mercury, lead, iron or copper, the compounds used are potentially toxic and they chelate other essential minerals such as calcium and zinc. As such, the risks and benefits must be weighed up before proceeding and it should only be administered by an experienced practitioner.

Metallothioneins (MTs) are a group of endogenously produced proteins and have been shown to provide protection against heavy metals.100,101 MTs have been shown to bind to toxic metals such as cadmium, lead, aluminum and inorganic mercury.100,102,103 In order to form their structures, MTs require zinc, copper, histidine and cysteine.104 Therefore it is wise to consider supplementing with these nutrients if there is heavy metal exposure.

Other promising supportive therapies have included the use of selenium,105 coline106 and glutathione101 to treat the ill health allegedly arising from mercury cytotoxicity and/or to reduce mercury levels.103 A combination of vitamin B complex, vitamin C, vitamin E and sodium selenite showed promising results on a range of biochemical and haematological parameters when used as adjuvant therapy during the removal of mercury amalgams.107

1 Crinnion WJ. Environmental medicine, part 1: the human burden of environmental toxins and their common health effects. Altern Med Rev. 2000;5(1):52-63.

2 Liska DJ, Bland JS. Emerging clinical science of bifunctional support for detoxification. Townsend Letter. 2002;231:42-43.

3 The dubious practice of detox. Internal cleansing may empty your wallet, but is it good for your health? Harvard Women’s Health Watch. 2008;15(9):1-3. [no authors listed]

4 Rogers S. Detoxify or die. Syracuse: Prestige Publishers, 2002.

5 William JR. Chemical sensitivity, volume 1. Boca Raton: Lewis Publishers, 1992.

6 Kaur SD. The complete natural medicine guide to breast cancer: a practical manual for understanding, prevention and care. Toronto: Robert Rose, 2003.

7 US Environmental Protection Agency. Breaking the cycle: 2001–2002 PBT Program Accomplishments. Online. Available: http://www.epa.gov/pbt/pubs/pbtreport2002.htm, 2002.

8 Landrigan PJ, Sonawane B, Mattison D, et al. Chemical contaminants in breast milk and their impacts on children’s health: an overview. Environ Health Persp. 2002;110:A313-A315.

9 Crinnion WJ. Environmental medicine, Part 4. Pesticides—biologically persistent and ubiquitous toxins. Altern Med Rev. 2000;5(5):432-447.

10 Young E. Rewriting Darwin: The new non-genetic inheritance. New Scientist 2008; 2664. Online. Available: http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg19926641.500-rewriting-darwin-the-new-nongenetic-inheritance.html, 26 March 2009.

11 Sotom AM, Vandenberg LN, Maffini MV, et al. Does breast cancer start in the womb? Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;102(2):125-133.

12 Luster MI, Rosenthal GJ. Chemical agents and the immune response. Environ Health Persp. 1993;100:219-226.

13 Hueser G. Diagnostic markers in clinical immunotoxicology and neurotoxicology. J Occup Med Toxicol. 1992;1:5-9.

14 Synder SH, D’Amato RJ. Predicting Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 1985;317:198-199.

15 Hungerford C. Good health in the 21st century: a family doctor’s unconventional guide. Melbourne: Scribe, 2006.

16 Haschek WM, Rousseaux CG. Handbook of toxicologic pathology. San Diego: Academic Press, 1991.

17 Buist R. Food chemical sensitivity. North Ryde: Collins/Angus and Robertson, 1990.

18 Kuhnlein HV, Receveur O, Muir DC, et al. Arctic indigenous women consume greater than acceptable levels of organochlorines. J Nutr. 1995;125:2501-2510.

19 Vial T, Nicolas B, Descotes J. Clinical immunotoxicity of pesticides. J Toxicol. 1996;48:215-229.

20 World Health Organization. Principles and methods for assessing autoimmunity associated with exposure to chemicals. Environmental Health Criteria Series no. 236. Geneva: WHO, 2006.

21 D’Cruz D. Testing for autoimmunity in humans. Toxicol Lett. 2002;127(1–3):93-100.

22 Massart F, Parrino R, Seppia P, et al. How do environmental estrogen disruptors induce precocious puberty? Minerva Pediatr. 2006;58(3):247-254.

23 Lee JR. What your doctor may not tell you about menopause. New York: Time Warner, 1996.

24 Boulakoud MS, Mosbah R, Abdennour C, et al. The toxicological effects of the herbicide 2,4-DCPA on progesterone levels and mortality in Wistar female rats. Meded Rijksuniv Gent Fak Landbourwkd Toegep Biol Wet. 2001;66(2b):891-895.

25 Foster WG, McMahon A, Villeneuve DC, et al. Hexachlorobenzene (HCB) suppresses circulating progesterone concentrations during the luteal phase in the cynomolgus monkey. J App Toxicol. 1992;12:13-17.

26 Epstein SS. The politics of cancer. Hankins, NY: East Ridge Press, 1998.

27 Bradlow HL, Davis DL, Lin G, et al. Effects of pesticides on the ratio of 16 alpha/2-hydroxyestrone: a biologic marker of breast cancer risk. Environ Health Persp. 1995;103(7):147-150.

28 Sharpe R, Shakkeback N. Are oestrogens involved in falling male sperm counts and disorders of the male reproductive tract? Lancet. 1993;41:1392-1395.

29 Carlsen E, Givercman A, Skakkebaek NE. Evidence for decreasing quality of semen during past 50 years. BMJ. 1992;305:609-613.

30 Colborn T, Dumanoski D, Peterson Myers J. Our stolen future. New York: Penguin, 1996.

31 Lund B, Bergman A, Brandt I. Metabolic activation and toxicity of a DDT-metabolite, 3-methylsulphonyl-DDE, in the adrenal zona fasciculata in mice. Chem Biol Interact. 1988;65:25-40.

32 Crinnion WJ. The effective use of botanicals, dietary agents and food additives to enhance the clearance of lipophilic xenobiotics from the body. Lecture given at American Association of Naturopathic Physicians Annual Convention, Phoenix, Arizona; 2008.

33 Ryan A. Inflammation linked to postmenopausal glucose metabolism. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1699-1705.

34 Porta M. Persistent organic pollutants and the burden of diabetes. Lancet. 2006;9535:558-559.

35 Davis DL, Dinse GE, Hoel DG. Decreasing cardiovascular disease and increasing cancer among whites in the United States from 1973 through 1987. JAMA. 1994;271:431-437.

36 Sharpe RM, Irvine SD. How strong is the evidence of a link between environmental chemicals and adverse effects on human reproductive health? BMJ. 2004;328:447-451.

37 Plaza S, Lamson D. How does it happen? An origin of mutations for malignancy. American College of Advancement in Medicine National Meeting; 2003.

38 Toyokuni S, Okamoto K, Yodoi J, et al. Persistent oxidative stress in cancer. FEBS Lett. 1995;358(1):1-3.

39 Davidson JF, Schiestl RH. Mitochondrial respiratory electron carriers are involved in oxidative stress during heat stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(24):8483-8489.

40 Wasserman M, Nogueira DP, Tomatis L, et al. Organochlorine compounds in neoplastic and adjacent apparently normal breast tissue. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1976;15:478-484.

41 Mussalo-Rauhamaa H. Occurrence of betahexachlorocyclohexane in breast cancer patients. Cancer. 1990;66:2124-2128.

42 Falck F. Pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyl residues in human breast lipids and their relation to breast cancer. Arch Environ Health. 1992;47:143-146.

43 Wolff MS, Toniolo PG, Lee EW, et al. Blood levels of organochlorine residues and risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:648-652.

44 Hunter DJ, Hankinson SE, Laden F, et al. Plasma organochlorine levels and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1253-1258.

45 Krieger N, Wolff M, Hiatt RA, et al. Breast cancer and serum organochlorines: a prospective study among white, black, and Asian women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:589-599.

46 Davis JR, Brownson RC, Garcia R, et al. Family pesticide use and childhood brain cancer. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1993;24:87-92.

47 Leiss J, Savitz D. Home pesticide use and childhood cancer: a case control study. Am J Pub Health. 1995;85:249-252.

48 Claggett S. 2,4-D Information packet. Northwest Coalition for Alternatives to Pesticides; 1990.

49 Eriksson M, Karlsson M. Occupational and other environmental factors and multiple myeloma: a population based case-control study. Br J Ind Med. 1992;49:95-103.

50 Anttila A, Pukkala E, Sallman M, et al. Cancer incidence among Finnish workers exposed to halogenated hydrocarbons. J Occup Environ Med. 1995;37:797-806.

51 Samoli E, Peng R, Ramsay T, et al. Acute effects of ambient particulate matter on mortality in Europe and North America: results from the APHENA study. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(11):1480-1486.

52 Committee of the Environmental and Occupational Health Assembly of the American Thoracic Society. Health effects of outdoor air pollution. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153(1):3-50.

53 Lee D, Ferguson C, Mitchell R. Air pollution and health in Scotland: a multicity study. Biostatistics. 2009;10(3):409-423.

54 Krzyzanowski M, Quackenboss JJ, Lebowitz MD. Chronic respiratory effects of indoor formaldehyde exposure. Environ Res. 1990;52:117-1125.

55 Liska DJ. The detoxification enzyme systems. Altern Med Rev. 1998;3(3):187-198.

56 Fujisawa T, Mori M. Influence of bile salts on beta-glucuronidase activity of intestinal bacteria. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1996;22(4):271-274.

57 Meyer UA, Zanger UM, Skoda RC, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of drug metabolism. Prog Liver Dis. 1990;9:307-323.

58 Ioannides C. Cytochromes P450: metabolic and toxicological aspects. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, 1996.

59 Golan DE, Tashjian AH, Armstrong EJ, et al. Principles of pharmacology: the pathophysiologic basis of drug therapy. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007.

60 Crinnion WJ. Components of practical clinical detox programs—sauna as a therapeutic tool. Altern Ther Health Med. 2007;13(2):154-156.

61 Chalmers RA, Valman HB, Liberman MM. Measurement of 4-hydroxyphenylacetic aciduria as a screening test for small bowel disease. Clin Chem. 1979;25:1791-1794.

62 Lindblad BS, Alm J, Lundsjo A, et al. Absorption of biological amines of bacterial origin in normal and sick infants. Ciba Found Symp. 1979;70:281-291.

63 Herron RE, Fagan JB. Lipophil-mediated reduction of toxicants in humans: an evaluation of an ayurvedic detoxification procedure. Altern Ther Health Med. 2002;8(5):40-51.

64 Molin M, Bergman B, Marklund SL, et al. Mercury, selenium, and glutathione peroxidase before and after amalgam removal in man. Acta Odontol Scand. 1990;48(3):189-202.

65 Hall DC. Nutritional influences on estrogen metabolism. Applied Nutritional Science Reports 2001; 1–8. Nutrition Publications Inc.

66 Harris PJ, Sasidharan VK, Robertson AM, et al. Adsorption of a hydrophobic mutagen to cereal brans and cereal bran and dietary fibres. Mutation Res. 1998;412:323-331.

67 Sera N, Morita K, Nagasoe M, et al. Binding effect of polychlorinated compounds and environmental carcinogens on rice bran fiber. J Nutr Biochem. 2005;16(1):50-58.

68 Han LK, Nose R, Li W, et al. Reduction in fat storage in mice fed a high-fat diet long term by treatment with saponins prepared from Kochia scoparia fruit. Phytother Res. 2006;20(10):877-882.

69 Kimura H, Ogawa S, Katsube T, et al. Antiobese effects of novel saponins from edible seeds of Japanese horse chestnut (Aesculus turbinate BLUME) after treatment with wood ashes. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56(12):4783-4788.

70 Hsu TF, Kusumoto A, Abe K, et al. Polyphenol-enriched oolong tea increases fecal lipid excretion. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;20(11):1330-1336.

71 Nakano S, Takekoshi H, Nakano MJ. Chlorella (Chlorella pyrenoidosa) supplementation decreases dioxin and increases immunoglobulin A concentrations in breast milk. J Med Food. 2007;10(1):134-142.

72 Morita K, Nakano T. Seaweed accelerates the excretion of dioxin stored in rats. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50(4):910-917.

73 Abraham GE. The safe and effective implementation of orthoiodosupplementation in medical practice. The Original Internist. 2004;11(1):17-36.

74 Daly AK, Cholerton S, Gregory W, et al. Metabolic polymorphisms. Pharmac Ther. 1993;57:129-160.

75 Kawajiri K, Nakachi K, Imai K, et al. Identification of genetically high risk individuals to lung cancer by DNA polymorphisms of the cytochrome P4501A1 gene. FEBS Lett. 1990;263:131-133.

76 Nebert DW, Petersen DD, Puga A, et al. Locus polymorphism and cancer: inducibility of CYP1A1 and other genes by combustion products and dioxin. Pharmacogenetic. 1991;1:68-78.

77 Bandmann O, Vaughan J, Holmans P, et al. Association of slow acetylator genotype for N-acetyltransferase 2 with familial Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 1997;350:1136-1139.

78 Meyer UA, Zanger UM, Skoda RC, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of drug metabolism. Prog Liver Dis. 1990;9:307-323.

79 Liska DJ. The detoxification enzyme systems. Alt Med Rev. 1998;3(3):187-198.

80 Wu JW, Lin LC, Tsai TH. Drug-drug interactions of silymarin on the perspective of pharmacokinetics. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;121(2):185-193.

81 Hoffman D. Medical herbalism: the science and practice of herbal medicine. Rochester: Healing Arts Press, 2003.

82 Das SK, Vasudevan DM. Protective effects of silymarin, a milk thistle (Silybum marianum) derivative on ethanol-induced oxidative stress in liver. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2006;43(5):306-311.

83 Goud VK, Polasa K, Krishnaswarmy K. Effect of turmeric on xenobiotic metabolising. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 1993;44(1):87-92.

84 Weng JR, Tsai CH, Kulp SK. Indole-3-carbinol as a chemopreventative and anti-cancer agent. Cancer Lett. 2008;262(2):153-163.

85 Minton JP, Walaszek Z, Schooley W. Beta-glucuronidase levels in patients with fibrocystic breast disease. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1986;8:217-222.

86 Pantuck EJ, Pantuck CB, Garland WA, et al. Stimulatory effect of brussels sprouts and cabbage on human drug metabolism. Clin Pharm Ther. 1979;25:88-95.

87 Appelt LC, Reicks MM. Soy feeding induces phase II enzymes in rat tissues. Nutr Cancer. 1997;28:270-275.

88 Barch DH, Rundhaugen LM. Ellagic acid induces NAD(P)H:quinone reductase through activation of the antioxidant responsive element of the rat NAD(P)H:quinone reductase gene. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:2065-2068.

89 Singh B, Kale RK. Chemomodulatory action of Foeniculum vulgare (Fennel) on skin and forestomach papillomagenesis, enzymes associated with xenobiotic metabolism and antioxidant status in murine model system. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46(12):3842-3850.

90 Offord EA, Mace K, Ruffieux C, et al. Rosemary components inhibit benzo[a]pyrene-induced genotoxicity in human bronchial cells. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:2057-2062.

91 Lisk DJ. Modulation of Phase I and Phase II xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes by selenium-enriched garlic in rats. Nutr Cancer. 1997;28:184-188.

92 Sircar S. Principles of medical physiology. New York: Thieme, 2009.

93 Tretzak Z, Shields M, Beckmann SL. PCB reduction and clinical improvement by detoxification: an unexploited approach? Hum Exp Toxicol. 1990;9:235-244.

94 Schnare DW, Ben M, Shields MG. Body burden reduction of PCBs, PBBs and chlorinated pesticides in human subjects. Ambio. 1984;13(5/6):378-380.

95 Seigel JM. Why we sleep. Sci Am. 2003;89(5):92-97.

96 Dickson Thom. Health of business, business of health. Seminar, Toronto, Ontario; May 2008.

97 Kondrot ED. Healing the eye the natural way. Carson City, NV: Nutritional Research Press, 2000.

98 Godfrey ME. EDTA chelation as a treatment of arterioscleros. NZ Med J. 1990;93:100.

99 Gordon GF. EDTA and chelation therapy: history and mechanisms of action, an update. Payson, AZ: Gordon Research Institute; 21 March 2009. Online. Available: http://www.gordonresearch.com/articles_oral_chelation/edtachel.html.

100 Szitanyi Z, Nemes C, Rozlosnik N. Metallothionein and heavy metal concentration in blood. Microchemical Journal. 1996;54(3):246-251.

101 Satoh M, Nishimura N, Kanayama Y, et al. Enhanced renal toxicity by inorganic mercury in metallothionein-null mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:1529-1533.

102 Ikemoto T, Kunito T, Anan Y, et al. Association of heavy metals with metallothionein and other proteins in hepatic cytosol of marine mammals and seabirds. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2004;23(8):2008-2016.

103 Guzzi G, La Porta CA. Molecular mechanisms triggered by mercury. Toxicology. 2008;244(1):1-12.

104 Wikipedia. Metallothionein. Wiki article. Online. Available: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metallothionein, 2008. 16 March 2009.

105 Rooney JP. The role of thiols, dithiols, nutritional factors and interacting ligands in the toxicology of mercury. Toxicology. 2007;234:145-156.

106 Clarkson TW, Strain JJ. Nutritional factor may modify the toxic action of methyl mercury in fish-eating populations. J Nutr. 2003;133:1539S-1542S.

107 Frisk P, Danersund A, Hudecek R. Changed clinical chemistry pattern in blood after removal of dental amalgam and other metal alloys supported by antioxidant therapy. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2007;120(1–3):163-170.