Chapter 53 Describing the deformities

• Weight loss patients present with anatomic deformities that are distinctly different from those encountered in nonbariatric esthetic surgery patients.

• It is useful to group these deformities by body area: the mid-body, breasts, arms, back, thighs, and face and neck.

• Mid-body contouring frequently requires circumferential abdominoplasty due to the circumferential excess of skin that involves the anterior abdomen, hips, outer thighs, lower back, and buttocks.

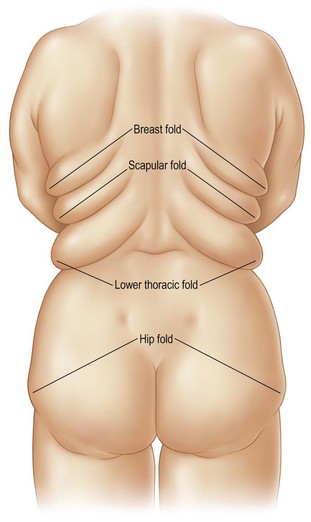

• Back deformities are consistent in their presentation and have been named according to their location: breast fold, scapular fold, lower thoracic fold, and hip fold.

• Patients younger than 45 years of age typically demonstrate enough skin contraction and elasticity that surgical correction of the face and neck is not needed.

Anatomic Considerations

We have grouped the body into six unique anatomic areas that require surgical attention.

Mid-body Excision

The mid-body is usually addressed with circumferential abdominoplasty. In contrast to the nonbariatric patient, these patients typically present with skin excess that extends onto the hips and lateral thighs and posteriorly to the back and buttocks. In patients with limited posterior excess, a near-circumferential abdominoplasty that extends to the posterior axillary lines may be indicated. In the era before laparoscopic bariatric surgery, up to 20% of patients presented with ventral hernias after open bypass surgery. These abdominal wall defects are frequently addressed at the time of body sculpting.1

Surgery of the Breast

We have described a variety of deformities of the female breast as well as a classification of these deformities (Table 53.1).2

TABLE 53.1 Classification of the Deformities of the Female Breast

The anatomic innervation to the breast has been described in multiple articles, dating back to Sir Astley Cooper’s description in 1840.3 Craig and Sykes identified the role of the third, fourth, and fifth anterior cutaneous nerves, and the fourth and fifth lateral cutaneous nerves, in supplying sensation to the nipple–areola complex.4 The importance of the lateral cutaneous branch of the fourth intercostal nerve as innervation to the nipple–areola complex was documented by Courtiss and Goldwyn.5 In light of these anatomic considerations, we generally employ a superolateral dermoglandular pedicle in our reduction mammaplasty and mastopexy cases.

Brachioplasty or Recontouring of the Arm and Axilla

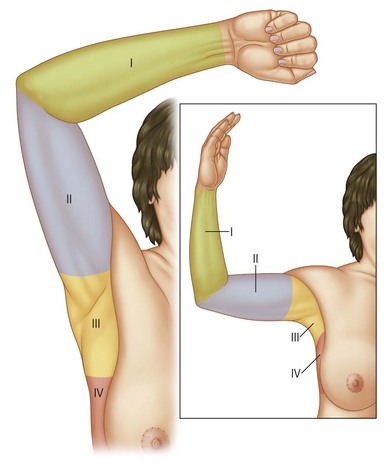

Excess skin in the upper extremity can extend from the chest wall distally to the elbow. We have described anatomic zones that are useful in planning the surgical approach (Fig. 53.1):6

Liposuction alone is rarely suitable in addressing the upper extremity deformity. Excision of the excess skin from the elbow to the axilla is generally the most effective approach. Authors have described a variety of incisions, including ones located posteromedially,6 inferiorly,7 and in the bicipital sulcus.8

Surgery of the Back

In the nonbariatric patient, back contouring is infrequently indicated or considered. In the weight loss patient, on the contrary, consistent deformities of the upper back are encountered. These deformities usually take the shape of four folds in distinct anatomic positions along the back. We have named the folds by region in order to standardize their nomenclature: breast fold, scapular fold, lower thoracic fold, and hip fold (Fig. 53.2).9 The lower two folds also are used to mark the superior line of excision during circumferential abdominoplasty surgery.

Surgery of the Thighs

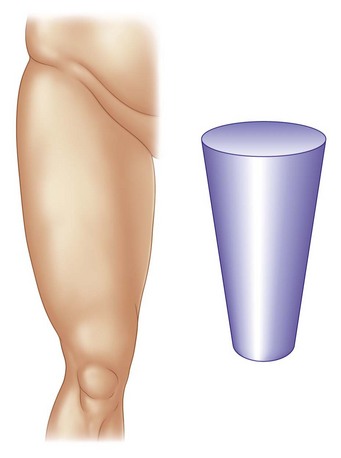

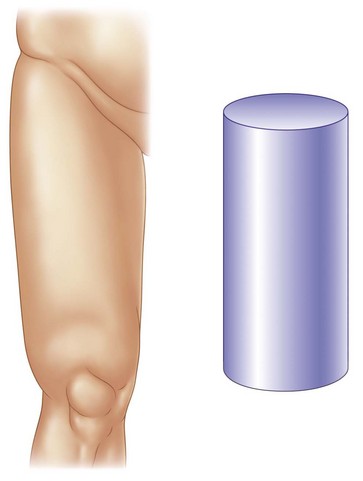

Patients often request contouring of both the medial and lateral thighs. Deformities take distinct shapes. Many patients present with thighs that are cone-shaped (Fig. 53.3), whereas others present with cylinder-shaped thighs (Fig. 53.4). Cone-shaped thighs present with greater vertical skin excess than horizontal and, thus, may require only a transverse excision; cylinder-shaped thighs, however, typically present with both vertical and horizontal excess that may require both vertical and transverse excisions.10

Surgery of the Face and Neck

The degree of skin excess and soft tissue ptosis observed varies with the patient’s age and amount of weight loss. Patients younger than 45 years often have enough skin elasticity to allow skin contraction after weight loss and avert noticeable deformity of the face and neck. Patients older than 45 years present with skin excess along the face and neck as well as variable degrees of soft tissue ptosis, including midfacial descent, that require surgical attention.11

Surgical Considerations

Mid-body Excision

In the majority of our patients, complete circumferential excision is accomplished. Generally, the procedure can be completed in 3 to 3.5 hours using our technique.12 This necessitates rotating the completely prepped patient directly on the operating room table, maintaining sterility. The procedure commences along the anterior abdomen and is continued as far posteriorly as possible. The patient is then rotated into a prone position. All tissue between the lower thoracic fold and the hip fold is marked for excision. No undermining of the back flaps is performed, which has drastically reduced the rate of skin flap necrosis and seroma formation. Drains are removed when output is less than 30 ml per day per drain. Pain control is assisted through use of a pulsed electromagnetic frequency (PEMF) device applied over the dressings.13

Breast Reconstruction after Weight Loss

As described above, weight loss patients demonstrate an augmented blood supply to the soft tissues, allowing the use of long de-epithelialized dermoglandular flaps. Given this anatomic feature unique to this patient population, we typically rotate dermoglandular flaps in continuity with a superior or superolateral pedicle to provide an autologous augmentation of the superior pole of the breast.14 Placement of a breast prosthesis may further increase projection and fullness.

Brachioplasty

As described in the “Anatomic Considerations” section, excess skin is observed from the elbow through the posteromedial arm and across the axilla onto the lateral chest wall. Our approach involves excising the excess tissue with a posteromedial incision in an S-shaped pattern. This accomplishes two goals: the posteromedial scar is more concealed with the arms adducted and the S shape redistributes the tissue over a longer length and decreases the potential for linear scar contracture. A Z plasty across the axilla reconstitutes the natural domed shape to the axilla.6

Chronology

Authors differ not only in the individual techniques employed to correct the anatomic deformities encountered in weight loss patients, but also in their timing. Many surgeons favor staging the surgeries by anatomic area, while some surgeons prefer to accomplish as much surgery as possible in fewer stages.15 Patient preference, of course, is paramount in determining the order and timing of these surgeries. Some patients may be most concerned with the appearance of their arms or face, as these areas are more difficult to conceal with clothing. In these cases, we have started with a facelift or brachioplasty as the first stage. On the other hand, the majority of patients defer to the recommendations of their surgeon. We favor dividing the surgeries in multiple stages, given consideration of blood loss and anesthesia time.

1 Herman CK, Hoschander A. Combination abdominal wall hernia repair and mid-body contouring. In: Strauch B, Herman CK. Encyclopedia of Body Sculpting after Massive Weight Loss. New York: Thieme; 2011:103–108.

2 Strauch B, Elkowitz M, Baum T, et al. Superolateral pedicle for breast surgery: An operation for all reasons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(5):1269–1277.

3 Cooper A. The Anatomy of the Breast. London: Longman; 1840.

4 Craig RDP, Sykes PA. Nipple sensitivity following reduction mammaplasty. Br J Plast Surg. 1970;23:165.

5 Courtiss E, Goldwyn RM. Reduction mammoplasty by the inferior pedicle technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;59:500.

6 Strauch B, Greenspun D, Levine J, et al. A technique of brachioplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:1044.

7 Cannistra C. Brachioplasty with an inferior scar. In: Strauch B, Herman CK. Encyclopedia of Body Sculpting after Massive Weight Loss. New York: Thieme; 2011:155–162.

8 Rubin JP, Michaels J. Correction of Arm Ptosis. In: Strauch B, Herman CK. Encyclopedia of Body Sculpting after Massive Weight Loss. New York: Thieme; 2011:163–174.

9 Strauch B, Rohde C, Patel MK, et al. Back contouring in weight loss patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(6):1692–1696.

10 Strauch B, Herman CK. Medial thigh contouring: cones and cylinders. In: Strauch B, Herman CK. Encyclopedia of Body Sculpting after Massive Weight Loss. New York: Thieme; 2011:265–271.

11 Herman CK, Diaz JF, Strauch B. Facial rejuvenation: indications and analysis. In: Strauch B, Herman CK. Encyclopedia of Body Sculpting after Massive Weight Loss. New York: Thieme; 2011:281–286.

12 Strauch B, Herman C, Rohde C, et al. Mid-body contouring in the post-bariatric surgery patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(7):2200–2211.

13 Strauch B, Herman C, Dabb R, et al. Evidence-based use of pulsed electromagnetic field therapy in clinical plastic surgery. Aesth Surg J. 2009;29(2):135–143.

14 Strauch B, Herman CK. Superolateral pedicle for reconstruction of the female breast. In: Strauch B, Herman CK. Encyclopedia of Body Sculpting after Massive Weight Loss. New York: Thieme; 2011:175–185.

15 Hurwitz DJ. Single stage total body lift after massive weight loss. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;52(5):435–444.