17 Dermatology

A swollen red leg

What is your diagnosis?

Cellulitis, probably due to streptococci gaining entry via the venous ulcer.

Differential diagnosis

• Acute allergic contact dermatitis: e.g. to dressings

• Necrotising fasciitis: black necrotic areas within cellulitic area.

Leg ulceration

Management

• Venous ulcers: elevation, exercise, compression dressings. Antibiotics if infected (always check Doppler pressures before considering compression as many ulcers have mixed venous and arterial aetiology). Adequate analgesia.

• Arterial ulcers: investigate arterial supply, dressings with NO compression. Adequate analgesia.

• Vasculitic ulcers: vasculitic screen, e.g. ANCA, ANA, rheumatoid factor.

• Neuropathic ulcers: keep ulcer clean and remove pressure or trauma from affected area.

Note: Operating on varicose veins rarely helps venous insufficiency problems – ‘re-plumbing’ of the veins is not possible.

Erythema nodosum

It presents with painful, tender, dusky blue red nodules, usually on the shins and lower limbs (Fig 17.1).

Make the diagnosis

• Spontaneous onset over days; evolution over a few days or weeks

• Single or multiple deep bruise-like nodules 1–10 cm diameter (better felt than seen)

• Predominantly affecting limbs (shins or lower limbs)

• No age or sex limitation (but young females more common)

Initial treatment

• Aspirin 600 mg as required (unless the identified cause of the EN).

• If severe symptoms and/or cutaneous ulceration, use dapsone (up to 100 mg daily)/steroids (30 mg daily decreasing course).

Note: monitor for haemolytic anaemia and avoid dapsone if G6PD deficient.

Urticaria and angio-oedema

Urticaria or hives is characterised by short-lived dermal swelling (weals) anywhere on the body (Fig. 17.2). These usually itch and, except in some subtypes, resolve without bruising within 24 h (often within 10–20 min). They can form bizarre serpiginous or annular-shaped lesions. The latter show central clearing, not central necrosis as seen in erythema multiforme.

Classification of urticarias

Acute

• Acute idiopathic urticaria and angio-oedema: accounts for > 90% of urticaria. A good history (not type 1 allergy testing) should exclude an allergic cause. Viral infections will sometimes set off an acute urticaria.

• Acute allergic: drug reactions, insect bites, foods (e.g. peanuts or seafood), can cause this type of reaction, as well as contact urticaria caused by, e.g. latex, tomatoes. A history of an almost immediate reaction (seconds to minutes) after contact with an allergen should alert one to this form.

General management

• Explanation of condition and likelihood of not identifying specific cause.

• Avoidance of non-specific factors, e.g. aspirin, NSAIDs, opiates.

• H1 anti-histamines (non-sedating or combination of daytime non-sedating H1 blockers and sedating H1 blocker at night); 90% of cases will respond to a non-sedating anti-histamine.

Preferred regimes if no contraindications

• Loratidine 10–20 mg daily or cetirizine 10–20 mg daily or fexofenadine 180 mg daily (all non-sedating anti-histamines).

• Sedative anti-histamines, e.g. hydroxyzine 25–50 mg at night.

Refer: to dermatology department if no response to anti-histamines.

Sun-induced rash

Differential diagnosis

Rare

• Lupus erythematosus (all forms)

• Solar urticaria (very rare) gives rise to a rash immediately after sun exposure.

Note: ‘prickly heat’ or ‘heat rash’(miliaria) are incorrect labels often given to polymorphic light eruption. This is an intensely itchy papular eruption in the flexures in hot humid conditions. It is due to blockage of the sweat ducts and does not require sun exposure and is also not on sun-exposed skin.

Information

UVA and UVB

• Medium wavelengths 280–310 nm (UVB): cause sunburn and long-term skin changes, e.g. ageing/cancer

• Long wavelengths 310–400 nm (UVA): do not cause sunburn (unless high doses through glass) but do cause photodermatoses. Also contribute to long-term skin damage

• Sunscreen preparations protect against UVB: the sun protection factor (SPF) number gives an indication of the amount of time that a person is protected against burning compared to unprotected skin. Most sunscreens also protect against UVA by utilising reflectants or chemical absorbers

Generalised rash or eruption

Management

• Rehydrate, plenty of fluids orally or IV

• Refer all cases to dermatology urgently

• Regular (hourly) observations, e.g. blood pressure, pulse fluid input/output chart, core temperature, weight.

Investigate for cause and treat as appropriate according to primary skin disease.

Pruritus

Causes of pruritus

Diseases of the skin associated with pruritus:

Systemic diseases associated with pruritus:

General management of urticaria

Treat primary skin disease. Refer to dermatology.

• Eczema: moisturisers and topical corticosteroids

• Psoriasis: tar, vitamin D3 ointments, mild to moderate topical steroids, dithranol (causes staining)

• Urticaria: non-sedating anti-histamines (see p. 553)

Investigations

• Primary skin diseases: most cases can be diagnosed on clinical grounds but scrapings for direct microscopy (scabies), punch biopsy (+ immunofluorescence), serum IgE for atopic disease are helpful

• Systemic diseases: FBC, U&Es, LFTs, iron, folate, vitamin B12, TFTs, autoimmune hepatitis screen, including mitochondrial antibodies, endomysial/gliadin antibodies. Consider serum Igs/protein electrophoresis/CXR in selected cases

Progress

• Scabies: malathion was given to him and his girlfriend. He was told to be careful in applying malathion all over his body, including crevices of his body and webs of his fingers. This should be washed off after 24 hours. Sexual contacts (if known), even if asymptomatic and no rash, should be given two treatments 7 days apart.

• Repeated scabies prescription leads to irritant dermatitis. Patients should be warned that the itching can go on for 1 month after successful treatment of scabies. Therefore give some crotamiton or topical steroid rather than further scabies prescription.

This patient’s scabies, on this occasion, was treated successfully because he was meticulous in the application of malathion.

Batchelor JM, Grindlay DJC, Williams HC. What’s new in atopic eczema? An analysis of systematic reviews published in 2008 and 2009. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 2010;35:823–828.

Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Section 6, J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011. Feb 7 Epub

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions (ADR)

Case history (1)

A 24-year-old man developed a severe sore throat and a fever. He was seen by his doctor, who diagnosed a streptococcal sore throat and prescribed amoxicillin. Two days later he presented with a macropapular rash (Fig. 17.4).

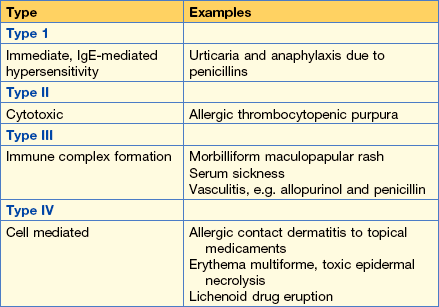

Classification

• Type A: augmented (~80% of all ADRs) – exaggerated responses to known effects of the drug. Predictable and dose-related, e.g. skin necrosis after extravasation of vincristine, alopecia due to cytotoxic agents, cheilitis due to retinoids, urticaria triggered by opiates causing mast cell degranulation.

• Type B: unpredictable/bizarre – idiosyncratic and therefore more difficult to diagnose (see below).

Pigmentation caused by drugs

• Long-term amiodarone or chlorpromazine: purple/slate-grey pigmentation on sun-exposed sites

• Long-term minocycline: blue/black pigmentation of skin, nails, buccal mucosa, scars (may be irrreversible)

• Mepacrine: reversible yellow skin pigmentation

• Bleomycin: flagellate erythema then hyperpigmentation of trunk.

Rashes potentially caused by drugs

There are many different reaction patterns and only a few common ones will be considered here:

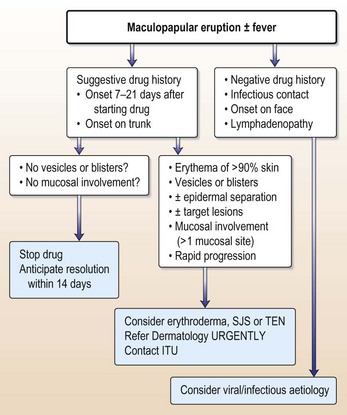

Maculopapular/exanthematic eruptions

This is the most common type of cutaneous ADR. It is thought to be a cell-mediated reaction (may also be immune complex) involving CD8 T cells (Table 17.1). There are widespread, symmetrical, itchy eruptions. Macules and papules may become confluent and develop into a sheet-like erythema, sometimes with fever and eosinophilia. When due to a drug, it usually begins on the trunk. Suspect a viral aetiology if it starts on the face and moves down and if there is associated lymphadenopathy and conjunctivitis. After withdrawal of the drug, it usually settles over 2 weeks.

Note: if this eruption has progressed rapidly over 24 h it may herald the onset of the following:

Anti-convulsant hypersensitivity syndrome..

Blood tests may show:

If the drug is not stopped immediately the patient may progress to multi-organ failure and need ITU care. All aromatic anti-convulsant drugs must be avoided in the future because further exposure is likely to lead to an even more severe reaction. Sodium valproate is a reasonable alternative.

The spectrum of erythema mutiforme (EM), Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)

The classification of these diseases is confusing in the literature.

Established skin disease exacerbated by drugs (Table 17.2)

• Psoriasis: can be destabilised by lithium and possibly beta blockers and anti-malarials.

• Acne: can be aggravated by progesterone-containing contraceptives, lithium and corticosteroids.

• Rosacea: worse with topical steroids.

• Peri-oral dermatitis (POD): caused and exacerbated by topical steroids.

| Maculopapular eruption | Photosensitivity | Lichenoid eruption |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | Thiazides | Gold |

| (Penicillins, sulphonamides) | Sulphonamides | Beta blockers |

| Anticonvulsants | Amiodarone | Quinine/anti-malarials |

| (Carbamazepine, phenytoin) | Tetracycline | Thiazides |

| NSAIDs | Nalidixic acid | Allopurinol |

Diagnosis of adverse drug reactions

The key elements to a diagnosis are a meticulous drug history and a high index of suspicion.

• Exclude other causes by history and examination.

• Take a careful drug history: remember to ask about over-the-counter preparations, e.g. laxatives, tonics and cough medicines, vitamins and complementary treatments.

• Start and stop dates of medication and relationship to onset of the rash.

• When the eruption begins from 7 to 21 days after the first administration of a drug or within 48 h if the drug has caused a similar reaction in the past, this is highly suggestive of an ADR.

• The timing is incompatible with an ADR if the drug was started after the onset of cutaneous or mucous membrane signs. If the onset is within 24 h of the first dose, or more than 21 days after stopping the drug, a drug aetiology is doubtful. If there are several drugs, each should be considered as a potential cause.

Investigations

• Blood eosinophilia (may be found in toxic erythema but is non-specific)

• Biopsy ‘may suggest but not prove a drug aetiology’:

• Blood level of drug (may be useful to check for over-dosage)

• If a fixed drug eruption is suspected re-challenge may be helpful (in other situations it is rarely justifiable for fear of precipitating a more severe reaction)

• Patch testing is helpful in patients with suspected allergic contact dermatitis (type IV hypersensitivity reactions) but cannot be used for systemic adverse drug reactions

Treatment

• Withdraw drug(s): symptomatic treatment with oral anti-histamines, topical steroids and moisturizers.

• Severe reactions (SJS and TEN) require supportive therapy and monitoring of infection, fluid balance and temperature. Patients may need ITU. Use of systemic immunosuppression may be considered if patients are seen within the first 24 h of onset.

• Give written information to patient and doctors to ensure no repeat exposure.

Figure 17.5 can be used as a guide to referral.

HIV and the skin

• Up to 90% of HIV-positive patients will develop a mucocutaneous disease, sometimes related to drug therapy.

• 30–40% of people with AIDS will suffer from three different dermatoses.

• A rash may be the presenting sign of HIV infection or AIDS (remember that up to 30% receive their diagnosis of AIDS and HIV at the same time, suggesting a large pool of undiagnosed patients).

What dermatoses have commonly been the presenting illness of HIV (or indeed other causes of immunosuppression)?

Why is the skin so frequently affected?

The exact mechanisms are not known but include:

• Immune deficiency: increased infection

• Poor immune surveillance: increased skin tumours

• Post infective: reactive arthritis

• Autoantibodies: Sjögren’s syndrome, polymyositis, ITP, pemphigoid, vitiligo, alopecia areata

• Aberrant immune function TH1 to TH2 switch: eczema, pruritus, PPE

• Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD): lichen planus, erythroderma.

What type of rashes are seen?

Many different rashes are seen, which can be arbitrarily divided:

HAART has reduced the incidence of all skin lesions.

How would you diagnose the rashes?

• Skin biopsies: both for all the routine stains and for culture of bacteria, fungi, viruses and AFBs.

• Investigation of other ‘organs’ such as blood, stools, sputum, bone marrow: furthermore, treatment is often problematic as HIV rashes (even those that are common in immunocompetent people) tend to be resistant to standard therapies and the use of immunosuppressive drugs is usually contraindicated.

Information

Cutaneous infections in HIV

• Bacterial: impetigo (Staphylococcus aureus), cellulitis/erysipelas (streptococci). Clinically, these infections tend to look much the same as in immunocompetent individuals. Deep-seated ecthyma may be seen.

• Fungal: dermatophyte and candidal infections are common in the skin and present typically. They often require systemic anti-fungal therapy for eradication (e.g. itraconazole 100 mg × 2 daily for 2–4 weeks)

What opportunistic infections occur in the immunocompromised and how would you distinguish between them?

A variety of normally non-pathogenic organisms have been described in AIDS and other immunosuppressed patients. Clinically they are difficult to distinguish:

• Cutaneous CMV may present with blisters, ulcers or necrotic lesion.

• Fungi are common culprits and may present with nodules (often deep subcutaneous) or scaly papules (Cryptococcus is seen in the UK whereas Histoplasma is more common in the US).

• Scabies presents typically with itchy papules and burrows in the web spaces, the wrists, genitalia, palms/soles. Crusted scabies (‘Norwegian scabies’) presents atypically with a rather crusted eczematous-looking rash often centred around the web spaces and it may not be itchy.

• Non-tuberculous or ‘atypical’ mycobacteria are a particular problem in advanced AIDS and present with papules, nodules, ulcers or sporotrichosis-like lesions.

These infections can be localised to the skin but also present as a systemic infection. Malaise, fever, abdominal pain, headache or diarrhoea may be non-specifically suggestive of systemic infection. Biopsy and culture is the best way to diagnose these rashes.

What types of malignancy occur in immunocompromised patients?

• The two most common types of skin cancers (BCC and SCC) appear to be increased in HIV-positive patients. They look the same as in immunocompetent patients.

• Malignant melanoma may be increased in prevalence. The clinical appearance is typical.

• Kaposi’s sarcoma is more common and more severe in AIDS patients (without available HAART therapy) than in classical KS or African KS. It presents as purplish-brown plaques and nodules. The nose, palate and genitalia seem common sites but remember they can spread internally. KS is predominantly seen in men who have sex with men with AIDS and, for unexplained reasons, the incidence declined during the 1990s but has been increasing again since 2000. There is a strong link between herpes virus type 8 and the development of all types of KS, although other factors might be involved, as not all people with HHV type 8 get KS.

• Lymphomas are more common with HIV and may present with lymphadenopathy, pleural effusions, night sweats and weight loss.

What are the more common ‘papulo-squamous’ dermatoses encountered in HIV patients?

The ‘papulo-squamous’ dermatoses encountered are:

In general, these rashes become more common (and severe) with progression of the disease.

PPE (pruritic papular eruption; also called itchy folliculitis)

The so-called unique HIV rash ‘eosinophilic folliculitis’ is probably a variant of PPE.

PPE tends to appear in more advanced HIV disease and becomes worse as CD4 counts fall.