Chapter 40 Dermatological presentations to emergency

Dermatology presentations to emergency department are common, accounting for 15–20% of visits,1 with the majority of presentations due to an infective aetiology or the result of drug reactions. Overall, there are four basic categories of dermatological presentation to emergency department (see Table 40.1).

Table 40.1 Isolated dermatological disorders

| Reason for presentation | Common or important clinical examples |

|---|---|

| New onset or flare | Eczema (atopic dermatitis)Papular urticaria—mainly a paediatric emergency presentation usually representing an exaggerated local hypersensitivity to an insect bite which can be clinically dramatic and/or severe, such as a blistering skin reaction |

| Subacute or chronic with complication | Impetiginised scabies, eczema |

| Dermatological presentations with systemic associations | |

| Fifth disease | Pregnant woman—increased risk of hydrops fetalis or aplastic crisis if underlying haematological disorder |

| Systemic disorders resulting in acute presentations with prominent cutaneous manifestations | |

| SLE/PAN/cholesterol emboli | Vasculitis, trash foot, broken livedoid eruption |

| Systemic disorders with associated cutaneous changes or disorders | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease and/or inflammatory arthritis | Pyoderma gangrenosum |

| Systemic disorders with unrelated/incidental cutaneous findings | |

| Common presentations | Seborrhoeic dermatitis (> 50% elderly but also more common in particular clinical settings, e.g. advanced HIV/AIDS, neurological disorders, especially Parkinson’s disease) |

HIV/AIDS, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome; PAN, polyarteritis nodosa; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus

Table 40.2 Terminology for skin lesions

| Lesion | Description |

|---|---|

| Bulla(e) | Large fluid-filled lesion > 0.5 cm in diameter |

| Cyst | Closed cavity/sac with epithelial lining containing solids or fluids |

| Discoid | Disc-shaped (nummular) |

| Erythema | Redness of the skin from vascular congestion or increased flow such as in inflammation |

| Macule | Flat alteration in colour and/or texture of the skin, e.g. colour change due to skin inflammation including erythema and/or hyper/hypopigmentation (change in melanin, haemosiderin); if larger than several centimetres, referred to as a patch |

| Nodule | Solid mass > 0.5 cm in diameter, palpable |

| Papule | Solid elevation of the skin < 0.5 cm in diameter |

| Petechiae | Pinpoint, flat, round, purplish red spots caused by intradermal or submucosal haemorrhage |

| Plaque | Solid, elevated lesion; may be formed by coalescence of papules |

| Purpura | Bleeding into the dermis; may be macular or papular |

| Pustule | Circumscribed collection of pus, commonly staphylococcal, but may be sterile in inflammatory and autoimmune dermatoses, e.g. pustular psoriasis |

| Telangiectasia(e) | Tiny visible blood vessels in the upper dermis ± inflammation |

| Verrucous | Rough, warty |

| Vesicle | Visible accumulation of fluid within or beneath the epidermis, < 0.5 cm |

| Wheal | Transient area of dermal oedema, pale, compressible, papular or plaque-like |

Surface characteristics: scale, crust, horn, excoriation, maceration, lichenification

Table 40.3 Diagnosis of dermatological disease

| Diagnosis | |

| Accurate characterisation of skin eruption | E.g. exanthematic eruption, skin rash due to or mimicking a viral infection |

| Isolated skin presentation versus any worrisome systemic involvement; concerning symptoms or associated findings | E.g. high fever (> 40°C) or ‘sick’ patient presentation |

| Differential diagnosis | |

| Infection: viral, bacterial, fungalDrug eruption: isolated (simple) exanthematic hypersensitivity reaction (and/or the manifestation of a systemic hypersensitivity reaction)Connective tissue disease, graft versus host disease (due to an acute disease flare and/or active inadequately controlled disease) | |

| Drug and other exposures | |

| Medications history | When medications, including over-the-counter and alternative or natural therapies, were started and/or stopped; any previous reactions to similar or crossreacting medications, vaccinations or injections |

| Other exposure | IVDU, environmental exposure, history of infective symptoms, travel |

| Diagnostic testing | |

| Diagnosis | Most diagnoses are suspected in emergency but confirmed at a later date. e.g. drug reactions largely a diagnosis of exclusion |

| Differential diagnosis | May require baseline (acute) viral and autoimmune serologyALWAYS perform a bacterial culture for M/C/S if itchy/weeping/crusted/purulent, ± viral culture if painful |

| Associated diseases/toxicities/complications | E.g. hepatitis, nephritis as part of a drug hypersensitivity syndrome and/or connective tissue disease flare. Drug hypersensitivity reactions are more common in those living with HIV/AIDS, lymphoma ± CTD |

| Determine probabilities | |

| Paediatric | Infectious aetiology more likely |

| Adult | Consider comorbidities and always consider drug causes, especially in the elderly |

| Dermatologist consult | |

| Urgent | E.g. suspected SJS/TEN |

| Organise follow-up/discuss | |

CTD, connective tissue disease; IVDU, intravenous drug use; M/C/S, microculture and sensitivity; SJS, Stevens-Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis

Table 40.4 Infective complications of dermatoses in immunocompetent patients

| Bacterial | |

| Viral | Herpes simplex virus 1, 2 |

| Fungal | Trichophyton rubrum and T. tonsurans (especially in rural and remote Indigenous populations) |

Table 40.5 Assessing patients with dermatological emergency presentations

MORPHOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION OF DERMATOLOGICAL PRESENTATIONS

1 Urticaria (hives) ± angio-oedema ± anaphylaxis

History

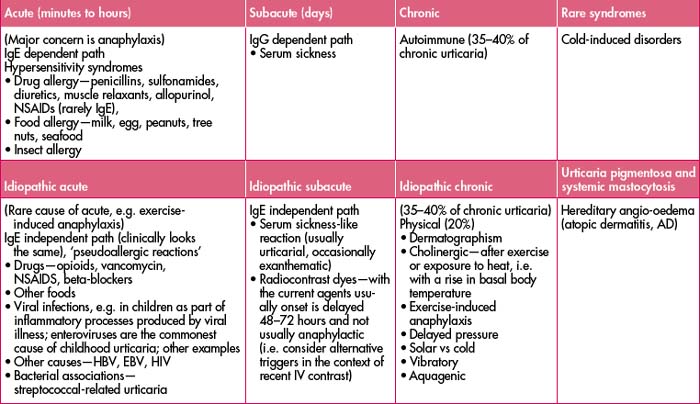

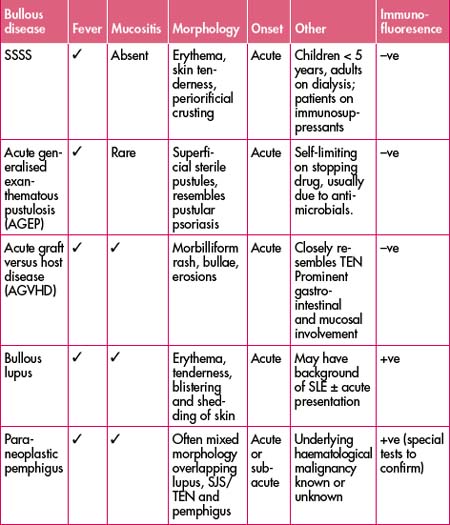

Onset of hives, swelling and itch in relation to stimulus. Acute presentations are typically seen in acute infections and hypersensitivity reactions to foods, medications or insect bites. See Table 40.6 below for classification of causes.

Clinical features

Differential diagnosis: erythema multiforme (EM)

Management: symptomatic ± acyclovir ± nutritional supplementation if there is significant mucosal involvement.

Management

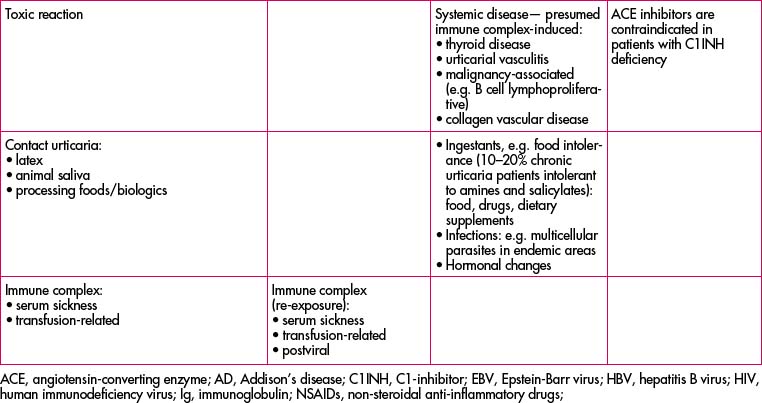

Refer to the flow chart, which includes anaphylaxis management, in Figure 40.1.

Table 40.7 Medications in angio-oedema, anaphylaxis and acute and ‘subacute’ urticaria

| Medication | Recommended adult dose | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Adrenaline | 0.5–1.0 mL of 1:1000 IM | Used if evidence ofanaphylaxis |

Table 40.8 Treatment of chronic urticaria (often a distressed patient with chronic symptoms presenting with a flare)

| Simple measures | Keep cool, loose clothing | |

|---|---|---|

| 4mg q4–6 h, max 24 mg/day | ||

| Useful in chronic urticaria in addition to H1 antihistamines | ||

| Cyproheptadine | 4 mg TDS | Sedating antihistamine plays an important role in chronic urticaria, e.g. with nocturnal exacerbations or insomnia due to urticaria, and appetite stimulant |

| Doxepin | 10–50 mg/day | H1- and H2-blocking properties, sedating, appetite stimulant, higher doses have anxiolytic and antidepressive effects |

| Acute severe episodes, avoid chronic use, especially in patients with chronic urticaria | ||

| Other immunosuppressives | For immunologist referral |

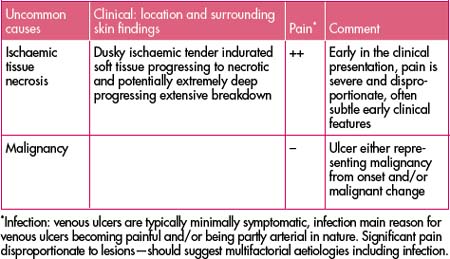

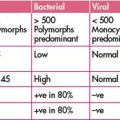

2 ‘Spotty, blanching’ exanthematic eruptions

Exanthematic eruption

Clinical features

Note: For exanthematic ‘spotty, blanching’ eruptions, ALWAYS consider the seriousness of the presentation: skin changes ± mucosal features ± systemic features, i.e. eruption plus systemically well versus eruption plus systemically unwell patient.

Investigations

Differential diagnosis

| Paediatric exanthematic eruption | Adult exanthematic eruption |

|---|---|

Kawasaki’s disease

Table 40.10 Features and management of common viral exanthems in paediatric patients

| Disease/virus | Signs/symptoms | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Enterovirus | Commonly respiratory or gastroenterology presentations ± exanthem or urticaria | Presentation dependent |

Diagnosis

Exanthematic drug eruptions

Simple exanthematic drug eruptions (common nuisance)

Management of ‘nonserious or simple’ exanthematic eruptions:

Drug hypersensitivity syndrome (DRESS)

Serum sickness-like reaction (SSLR)

SSLR has multiple causes including drug-induced cefaclor, amoxicillin, minocycline etc.

Differential diagnosis: autoimmune connective tissue disease, infections such as hepatitis B or C and infective endocarditis, and lymphoma due to cryoglobulins and/or circulating immune complexes.

Table 40.11 Comparison of serum sickness versus serum sickness-like reaction (SSLR)

| Serum sickness | SSLR | |

|---|---|---|

| Skin: eruption | Urticarial and vasculitic | Exanthematic and urticarial |

| Fever | ✓ | ✓ |

| Arthritis | ✓ | – (arthralgia only) |

| Renal involvement | ✓ (nephritis) | – |

| Serositis/carditis | ✓ | – |

| Associated drugs | Streptokinase, antivenoms, digoxin, immune Fab | Cefaclor, buspirone, infliximab, rituximab, griseofulvin |

| Histopathology | Systemic vasculitis | Inflammatory or unknown |

| Management |

3 Generally red, inflamed and scaly: erythroderma13

Exfoliative erythroderma

Atopic dermatitis (AD) flare7

Differential diagnosis

Contact dermatitis allergic or irritant, photodermatitis and contact urticaria.

Management

Infections

Sunburn (‘photo-distributed’/‘exposed’)

Treatment

Photodermatitis

4 Blistering/shedding of skin

Varicella zoster/herpes zoster

Note: Always suspect herpes in any neonate with a vesiculobullous or eroded weeping eruption.

Clinical features

Investigations

Diagnosis is clinical; however, confirmation by PCR. Highest yield is from a fresh vesicle by breaking it aseptically with a 19-gauge needle and scraping from the base with a viral culture swab.

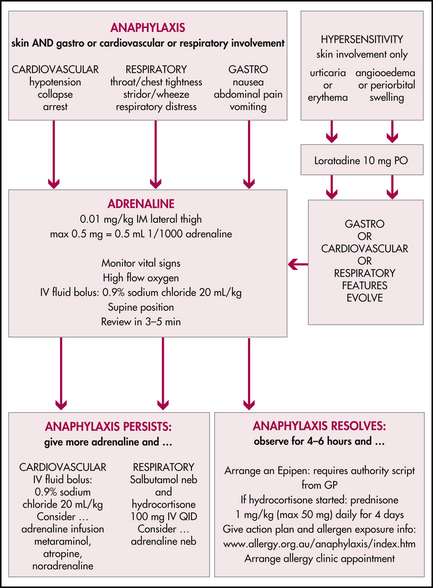

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS)

Serious cutaneous adverse reaction (SCAR)

SCAR includes Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).

Note: If SJS or TEN is suspected, urgent specialist review is required.

This is potentially life-threatening due to multisystem involvement and skin-barrier breakdown. Epithelial loss predisposes to bacterial and fungal infections, septicaemia and severe fluid loss with electrolyte disturbance. Mortality ranges from 5% in SJS to 30% in TEN. Mucous membranes are usually involved, with erythema and erosions of buccal, genital and ocular mucosa. Severe ophthalmic involvement may lead to permanent scarring and blindness.

| Mucous membrane involvement, especially if |

|---|

Management

Note: STOP potentially causal drugs as soon as diagnosis suspected. This saves lives and is especially for longer acting medications, e.g. traditional aromatic anticonvulsants (phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbitone along with lamotrigine).

Pemphigus vulgaris

Bullous pemphigoid

Grade 4 acute graft versus host disease (AGVHD)

5 Vasculitis/purpuric vs ischaemic/necrotic skin ± deeper tissues

Table 40.16 Vasculitis/purpuric vs ischaemic/necrotic skin ± deeper tissues

| Differential | Clinical scenario |

|---|---|

| Meningococcaemia | Always consider and if considered always treat |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | Sick, septic patient reflecting underlying illness |

| Vasculitis (venular or usual leukocytoclastic vasculitis)—unknown, infection, connective tissue disease, malignancy, drug, multifactorial, including Henoch Schönlein purpura | Often multifactorial aetiology; recent illness, sepsis, drug-inducedThe three Ps of small vessel vasculitis: painful palpable purpura |

| Vasculitis (larger vessel e.g. arterial, e.g. PAN) | Usually systemic disorder, consider infection and drugs |

| Embolic; septic, cholesterol etc | Background comorbidities e.g. IHD, IVDU, trauma |

| Heparin and warfarin necrosis | Anticoagulant therapy |

| Haemorrhagic and bullous cellulitis | Consider deep fungal infections not only in the immunocompromised population but also in the general population |

| Haemorrhoagic or necrotic infections of deeper ‘soft’ tissue including necrotising fasciitis | General immune and immunosuppressed |

| Metabolic and intravascular disorders including: calciphylaxis (ischaemic tissue necrosis, ITN)/catastrophic anticardiolipin syndrome (reticulate ‘dusky’ or cyanotic ± painful purpuric changes early on) | Note: Catastrophic anticardiolipin syndrome may have prominent central nervous system symptoms and signs |

Meningococcaemia

Management

Necrotising fasciitis

Treatment is based on clinical suspicion with broad antimicrobial cover.

Clinical features

The organisms can be introduced through minor cuts, burns, blunt trauma or surgical procedures.

Type I necrotising fasciitis is caused by mixed anaerobes, gram-negative aerobic bacilli and Enterococci are implicated in type I, and type II is group A Streptococci.

Diagnosis

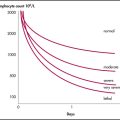

COMMON LOWER LEG EMERGENCY PRESENTATIONS—ULCERS/WOUNDS

Erysipelas

Superficial streptococcal cellulitis with a well demarcated edge. Face is common for erysipelas. Haemophilus influenzae is an important cause of facial cellulitis in children, often associated with ipsilateral otitis media. Immunocompromised patients have a variety of potential bacteria. Often strikes in the same place twice. Recurrent bouts need long-term prophylactic penicillin; consider referral to infectious diseases.

| Disease | Signs/symptoms | Management |

|---|---|---|

Box 40.10 Consider admission in the context of ulcer presentation for patients with the following

Systemic illness e.g. significant fever and constitutional symptoms

BITES12

ITCHING/PRURITUS13

Pruritus varies in duration, localisation and severity.

Box 40.11 Common causes of itching

Scabies

Management

All members of the same house should be treated at the same time.

Important that malathion 0.5% aqueous preparation is favoured because it does not irritate excoriated or eczematised skin; wash off after 24 hours.

Box 40.13 Scabies treatment (print out and give to patient)14

Sullivan J, Commens C. Patient information pages. Australasian College of Dermatologists website. http://www.dermcoll.asn.au/

Common medications

Table 40.19 Carrier vehicle: lotion—low potency, cream—mid-potency, ointment—high potency

| Potency | Name | Areas of use |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 1% hydrocortisone TDS (cream combined with moisturiser usually most appropriate) | Face, axillae, genital areas |

| Moderate | Betamethasone valerate 0.02% |

WOUND AND ULCER CARE IN EMERGENCY

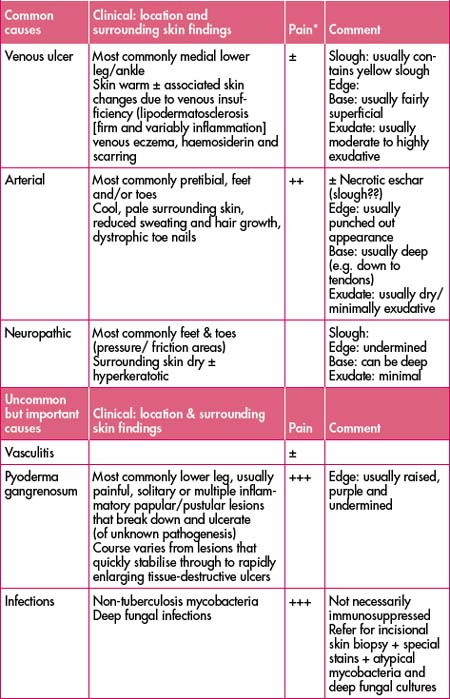

Ulcers on lower legs are slower to heal than other body sites and in particular benefit from efforts to address underlying factors to optimise conditions for healing. See Table 40.20 for the causes of leg ulcers. In some patients they are multifactorial in their causation.

Evaluation of ulcers

Management of leg ulcers/wounds

| Treat | Example | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Correct or address underlying cause | Venous hypertension | Compression mainstay of treatment |

| Infection vs colonised ulcers | Treat if clinically infection, e.g. surrounding skin inflammation and/or fever |

1 Freiman A., Borsuk D., Sasseville D. Dermatologic emergencies. CMAJ. 2005;173(11):1317-1319.

2 Amar S.M., Dreskin S.C. Urticaria. Prim Care Clin Office Pract. 2008;35:141-157.

3 Shear N.H., Knowles S.R., Sullivan J.R., et al. Cutaneous reactions to drugs. In Austen K., editor: Dermatology in general medicine (Fitzpatrick), 6th edn, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003.

4 Calabrese J.R., Sullivan J.R., Bowden C.L., et al. Rash in multicenter trials of lamotrigine in mood disorders: clinical relevance and management. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(11):1012-1019.

5 Sullivan JR. HIV and skin disease. Australasian College of Dermatologists website. http://www.dermcoll.asn.au/public/a-z_of_skin-hiv_and_the_skin.asp#01.

6 Dyer J.R., Einsiedel L., Ferguson P.E., et al. A new focus of Rickettsia honei spotted fever in South Australia. MJA. 2005;182(5):231-234.

7 Ong P.Y., Bogunewicz M. Atopic dermatitis and contact dermatitis in the emergency department. Clin Ped Emerg Med. 2007;8:81-86.

8 Heymann W. Toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5):867-869.

9 Hertzberg M., Schifter M., Sullivan J., et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus in two patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: significant responses to cyclophosphamide and prednisolone. Am J Hematol. 2000;63(2):105-106.

10 Browne B.J., Edwards B., Rogers R. Dermatologic emergencies. Prim Care Clin Office Pract. 2006;33:685-695.

11 Buddin D., Beddingfield F. Recognising emergent dermatologic conditions. Emerg Med. 2004;3:26.

12 Schlessinger J. Animal bites. eMedicine from WebMD (Online). May 2007. Available: http://www.emedicine.com/derm/topic676.htm.

13 Graham-Brown R., Burns T.. Lecture notes. Dermatology, 9th edn, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2007.

14 14Sullivan JR, Commens C. Patient information pages. Australasian College of Dermatologists website. http://www.dermcoll.asn.au/public/a-z_of_skin.

Allaboutacne website. http://www.allaboutacne.info/.

Australian Therapeutic Guidelines. Classification of allergic and anaphylactic reactions. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2006;18(2):155-169.

Bowen T., Cicardi M., Farkas H., et al. Canadian 2003 international consensus algorithm for the diagnosis, therapy, and management of hereditary angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(3):629-637.

DermNetNZ website. http://www.dermnet.org.nz/.

Sigurdsson V., Toonstra J., Hezemans-Boer M. Erythroderma. A clinical and follow-up study of 102 patients, with special emphasis on survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(1):53-57.

Virtualskinconsult website. http://virtualskinconsult.com/.

Weller R., Hunter J.A.A., Savin J., et al. Clinical dermatology, 4th edn. Wiley-Blackwell; 2008.

Special thanks for assistance with this chapter go to Dr Maureen Rogers MB BS FACD, Dermatologist Consultant Emeritus, Westmead Children’s Hospital.