35 Dermatologic Conditions and Symptom Control

Skin disorders are often encountered in pediatric palliative care patients and can have both significant physical and emotional impact on a child’s well being. The skin is the largest organ in the body and accounts for 15% of a person’s body weight. Its major function is to provide protection from the external environment. This protection allows intimacy through the ability to touch and be touched. The skin is visible to the external world and its appearance can strongly affect a child’s self-image and a parent’s perception of the child. It is critical to identify dermatologic disorders and use an interdisciplinary team to take a whole-person approach to the treatment (Table 35-1).

TABLE 35-1 The Roles of Team Members in the Treatment of Wounds

| Disipline | Role |

|---|---|

Psychosocial Impact of Dermatologic Conditions

In order to understand the psychosocial impact of skin disorders on pediatric palliative care patients, it is important to understand how skin disorders affect body image. Body image is a central part of self-concept and self-esteem, which is broadly defined as “the composite of thoughts, values, and feelings that one has for one’s physical and personal self at any given time.”1 Reactions to physical changes in the body often depend on whether the change involves an emotionally loaded body part or function or whether it results in a visible disfigurement. Physical appearance and attractiveness are major issues confronting adolescents, and their body image becomes a central aspect of their identity development.2 As a result of physical changes in appearance, others may stare or avoid looking at a child. Thereafter, the affected child may suffer emotionally and may withdraw socially. Although psychosocial research has been limited, studies have suggested that altered body image can interfere with daily functioning and has been associated with grief, anxiety, depression, social introversion, social avoidance behaviors, negative self-esteem, and avoidance of intimate relationships.3,4

A common diagnosis causing dermatologic symptoms in pediatric palliative care patients is cancer. The diagnosis of cancer is frequently associated with psychosocial and emotional issues. Studies indicate that children of all ages experience distress due to the effects of cancer treatment.5 A diagnosis of cancer often leads to multiple changes in physical appearance. These changes frequently include hair loss, presence of a central venous catheter, weight changes, and scars from surgery. The body-altering side effects of cancer have been reported by adolescents as the worst aspect of their disease.6 The adolescents’ sense of self-worth can be affected to such a degree that they withdraw socially from their friends and family. Physical changes due to cancer or its treatment can be devastating to a child’s self-image and can place the child at an increased risk for psychological and adjustment issues.7–9

Regardless of the underlying medical diagnosis, intact skin allows for intimacy and the ability to touch and be touched. Many teams that provide palliative care include massage or healing touch treatments to provide moments in which the child feels relaxed. Furthermore, touch is an important means for a child’s family to express their emotions and care. Any change in a child’s body image is likely to change closeness and intimacy through touch. Loss of intimacy may elicit psychological responses that become enduring and pathological, such as depressive symptoms and social anxiety. It should, however, be kept in mind that psychological responses subsequent to the development of dermatological conditions may not be simply the result of the skin condition, but be part of the child dealing with a life-threatening illness.10

Another important consideration is the psychological impact of pain that can be caused by the treatment of skin conditions. Painful treatments may include such things as changing wound dressings and physical therapy. The wound is a constant reminder that one’s body has been changed and nurses need to be attentive and sensitive to patient responses during wound care.11 Moreover, patients with wounds often report symptoms of depression and anxiety due to the pain.12 Another important factor to consider is that effects of dermatologic conditions such as pain, skin breakdown, and scarring may lead to limitation of motion and activity. These limitations may become a major cause of distress for the child.13 Young children particularly cope with distressing situations by engaging in play therapy. If the child’s play routine is limited due to a skin symptom, coping may be limited, too.

A skin disorder may also affect a child’s sense of self-competence as well as relationships with parents, siblings, or friends. Children and adolescents rely on different sources of social support. Children rely more on their parents and siblings, whereas adolescents obtain much of their support from peers. Peers are influential in the adolescents’ self-definition and self-evaluation. If adolescents become isolated from their peers, this may contribute to a sense of social deprivation and can put the adolescent at increased risk for depressive symptoms. Also, older adolescents facing changes in body image may be less likely to establish intimate relationships.14 If children or adolescents have less social contact, this may have significant implications on their ability to cope with the skin disease and their overall quality of life. It is important to facilitate and encourage connections between family members and peers. This can be done by open communication and by encouraging interactions with friends. These interactions may be face to face, through e-mails or social networking websites, or by phone calls between the child and his or her friends.

Adjustment to dermatologic symptoms is influenced by individual needs and coping behaviors, family support, palliative medicine treatment team, sex, age, and location of the injury.15 A powerful mediator of psychological problems is good communication among the care team, family, and child.16 Many of the problems experienced by the child require a combination of psychosocial and integrative medicine interventions. Possible psychological interventions are assisting the child to explore activities in which he or she is able to expose thoughts and feelings without feeling vulnerable. This includes validating their feelings, rationalizing, and developing a sense of acceptance. The treatment could be a combination of counseling and art therapy. Further, it may be helpful to allow the family to incorporate integrative modalities, such as guided imagery, healing touch, hypnosis, acupuncture, aromatherapy, or other mind-body skills. However, keep in mind that caring for children with skin conditions should not be separated from educating and helping families cope with the impact of the conditions.

Generalized Pruritus

Pruritus is an unpleasant cutaneous sensation that provokes the desire to scratch. It can be distressing and sometimes difficult to treat. It may lead to sleep disturbance, difficulty concentrating, anxiety, depression, and agitation. Left inadequately managed, it can have a significantly negative impact on a child’s quality of life.1

A recent position paper by the International Forum for the Study of Itch identifies six categories for the classification of pruritus based on its etiology: dermatologic disease, systemic disease, neurologic, psychiatric, and/or psychosomatic, mixed, and others.2 The causes of pruritus are numerous, and an extensive list is included in the paper published by the International Forum. Identifying the etiology of pruritus can be helpful when formulating a therapeutic approach. This chapter will address only the most common causes of pruritus in the palliative care setting.

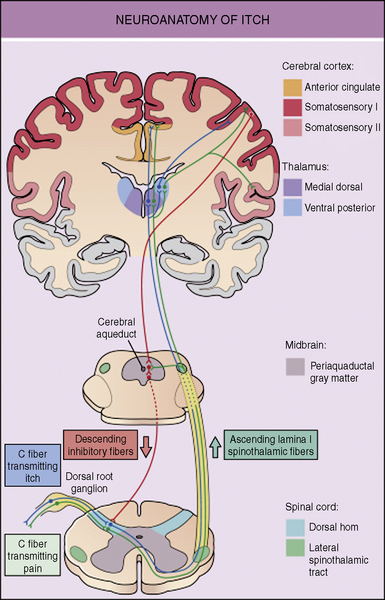

Pathophysiology of pruritus

The neuronal pathways for the transmission of pruritus are thought to be closely related to, but distinct from, pain pathways. The skin is densely innervated by afferent C-fibers. These C-fibers transmit signals that lead to both the perception of pain and pruritus. About 80% of the C-fibers are activated by mechanical stimuli, being mechano-sensitive, while the remaining 20% are activated by chemical stimuli, including histamine, called mechano-insensitive. It is likely that some combinations of mechano-insensitive and mechano-sensitive C-fibers are responsible for the transmission of the itch signal to the dorsal root ganglia.3 Dorsal horn neurons then carry the itch signal up the spinal cord to the thalamus. Functional MRI imaging of the brain has shown activity in multiple areas of the brain, which encode sensory, emotional, attention-dependent, cognitive, and motivational aspects of itch.4 The perception of itch causes the response of scratching. Scratching creates a mild pain stimulus, which activates fast-conducting low-threshold nerve fibers that inhibit itch. It is believed that itch is under tonic inhibitory control of pain-related signals. It has also been demonstrated that μ-opioid receptor antagonists can have antipruritic effects but may intensify pain (Fig. 35-1).5–8

When pruritus is caused by dermatologic disease, peripheral C-fibers must be activated to transmit an itch signal. Histamine is the itch-stimulating substance, pruritogen, that is most typically targeted when treating itch, but there are other substances that stimulate itch including acetylcholine, bradykinin, endothelins, interleukins, leukotrienes, neurotrophins, prostaglandins, proteases, and kallikreins. These pruritogens can be released from various intracutaneous cell types. When these substances stimulate C-fibers, neuropeptides, such as substance P, are released. The neuropeptides then act on a variety of non-neuronal cell types, such as mast cells, which release further pruritogens thus creating a positive feedback loop and increases itch. Itch leads to scratching, which causes inflammation and the release of more pruritogens. Breaking this itch-scratch cycle can be particularly challenging. Recently investigators have identified ion channels, called transient receptor potential channels, that when stimulated, desensitize sensory afferents by depleting neuropeptides such as substance P. This interrupts the interplay between sensory neurons and mast cells and is a promising focus for the development of future therapies for pruritus.3 Capsaicin, which is being used in adults to treat pruritus, is an example of a medication that works through this mechanism.

The pathophysiology of pruritus caused by systemic disease is not fully understood, but it is often caused by increased levels of pruritogens, including endogenous and exogenous opioids. Itch of the neurological classification arises secondary to damage of nerves anywhere along the afferent pathway. Nerve damage can be seen in peripheral neuropathies, nerve compression or cerebral processes such as tumors, abscess, or thrombosis. Itch caused by psychiatric and/or psychosomatic disease can occur in disorders such as obsessive-compulsive disorder and parasitophobia. It is believed that both acute and chronic stress can trigger or enhance pruritus.9

Assessment

There are few assessment tools to evaluate the severity of pruritus in children. The tools that do exist are designed to be used in specific conditions, such as atopic dermatitis.10 In older children visual analog scales can be used to evaluate itch intensity. In the research setting a quantitative measure of pruritus can be obtained by a device that is able to measure the vibrations of the fingernails in the act of scratching.11

Management of Specific Conditions

It can be quite difficult to keep children from scratching areas that itch. Children often scratch irritated areas in their sleep or without thinking about it. It is crucial to keep a child’s fingernails cut short to prevent significant damage to the skin from scratching. Gloves or mittens can be place on children’s hands but they are often difficult to keep in place and can limit the child’s function. Case reports have suggested that hypnosis can be effective in reducing pruritus. This therapy may be a helpful adjuvant therapy for itch that is difficult to treat.12–14

Opioid-induced pruritus

Generalized pruritus that may localize to the face and trunk is a common complication of parenteral or neuraxial opioid administration. Pruritus can also be seen with the administration of oral opioids. It is difficult to estimate the incidence of opioids-induced pruritus in children for several reasons including limited data, variation between opioids and routes of administration, and lack of uniformity in methods of evaluation of pruritus. The incidence has been reported to be as high as 77% with parenteral administration of opioids in the postoperative setting.15 Among children with cancer-related pain, the incidence has been reported to be 28% with administration of oral or parenteral opioids.16 It is generally accepted that the incidence of pruritus is higher in neuroaxial administration of opioids than in parenteral administration. One 2006 study shows an incidence of 18% with parenteal opioids and 30% with epidural opioids.8

The mechanism of opioid-induced pruritus is not fully understood. It is known that orally and parenterally administered morphine can cause the release of histamine from mast cells, but fentanyl does not.17–19 Because both morphine and fentanyl are known to cause pruritus, this argues against histamine playing a significant role in opioid-induced pruritus. Furthermore, in studies done in primates, the administration of a histamine antagonist did not attenuate scratch induced by morphine.20 Any reported benefit of the use of H1-antihistamines in the treatment of opioid-induced pruritus is most likely related to the sedative properties of the medication. It is likely that opioid-induced pruritus is mediated centrally through μ-opioid receptors.20

In the initial management of pruritus caused by morphine, it may be helpful to change from morphine to an alternative opioid such as hydromorphone or fentanyl. If this is not effective, an opioid receptor antagonist can be administered in conjunction with the patient’s opioid. It is important, however, that the opioid antagonist be used in a low enough dose that it does not reverse the analgesia achieved by the opioid. Both naloxone and naltrexone have been studied. Naloxone can be administered at a starting dose of 0.25 mcg/kg/hr to 1 mcg/kg/hr. It is believed that doses of more than 2 mcg/kg/hr are likely to cause an unacceptable degree of reversal of the analgesic effect of the opioid. A pilot study done in children in sickle cell crisis found that patients tolerated co-administration of naloxone and morphine.5 A second study of 46 pediatric postoperative patients found that concomitant administration of low-dose naloxone and morphine PCA significantly reduced opioid-associated pruritus.15

Opioid agonist-antagonists, including nalbuphine and butorphanol, have also been studied as agents to reduce pruritus. Results of these studies have been mixed and studies are limited in the pediatric population. One study of 184 pediatric patients found that nalbuphine 50 mcg/kg IV given as a one-time dose was not effective in the treatment of postoperative opioid-induced pruritus.8 Nonetheless, additional studies are warranted. While these drugs have conceptual advantages over pure opioid antagonists in that they do not reverse the analgesic effect to the opioid, in combination with pure agonist opioids, they risk the precipitation of an opioid withdrawal syndrome and worsened pain. These medications act as antagonists at the μ-receptor and as agonists at the kappa-receptor. It appears that activation of kappa receptors attenuates morphine-induced itch without interfering with analgesia.21

Cancer-specific

The most effective treatment for cancer-related pruritus is anticancer therapy. In palliative care, however, many patients are responding poorly to or are no longer receiving disease- modifying therapies. In these patients, other approaches to the treatment of the pruritus must be identified. There is very limited data on the treatment of pruritus associated with cancer. In Hodgkin lymphoma there are case reports suggesting that the H2-receptor antagonist, cimetidine, is effective in treating pruritus.22 Corticosteroids typically given in conjunction with palliative chemotherapy can also relieve itch in late-stage Hodgkin lymphoma. Case series that have included pediatric patients suggested that pruritus caused by solid tumors may respond to the serotonin selective reuptake inhibitor paroxetine.23 While paroxetine’s antidepressant effects can take weeks to see, its antipruritic effects may be seen in as little as 24 hours after administration. In carcinoid tumors, blocking serotonin with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, such as odansetron, may be helpful.

Cholestastis

Cholestasis occurs in children of all ages, but it is particularly common in the neonatal period. The incidence of neonatal cholestasis is estimated to be approximately 1 in 2500 live births.24 The mechanism by which cholestasis causes pruritus is unclear, but elevated levels of circulating bile acids and endogenous opioids are both believed to play a role. It is also probable that the serotonin neurotransmitter system is involved. Recently the role that the serotonin neurotransmitter system plays in pruritus caused by cholestasis has been explored. There are studies in adults suggesting that the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist ondansetron, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors paroxetine and sertraline, and the noradrenalin and specific serotonin antagonist mirtazapine can be effective therapies.25–29 The pruritus of cholestasis is not thought to be mediated by histamine. Any relief that patients perceive with the administration of antihistamines is likely related to the sedating effects of the medication. It is of interest to note that if a patient progresses to liver failure, then pruritus often resolves.

First line therapy for pruritus caused by cholestasis is typically a medication directed at decreasing the level of circulating bile acids. Medications that can be used to achieve this result include nonabsorbable anion exchange resins such as cholestyramine, the hydrophilic bile acid ursodeoxycholic acid, and the hepatic enzyme inducers rifampin and phenobarbital.26,30–33 Nonabsorbable anion exchange resins are not effective in the case of complete biliary obstruction because the bile acids must reach the intestine for the medication to be effective. They are usually avoided in infants with portoenterostomy for biliary atresia because of concern about accumulation of the drug at the anastomosis causing obstruction.

If decreasing the level of circulating bile acids is ineffective or only partially effective, an opioid antagonist can be administered. The opioid antagonists naloxone, nalmefene, and naltrexone have all been shown to be helpful.34–37 Tolerance to these medications may develop over time, requiring dose escalation. Patients may experience symptoms of opioid withdrawal if they are treated with opioids; this can limit the medications’ usefulness.

Surgical interventions may also be helpful if medical management has not been successful and surgery makes sense within the goals of care. Procedures including partial external biliary diversion and terminal ileal exclusion have been shown to decrease pruritus in some children with intrahepatic cholestasis.38,39 In pruritus caused by extrahepatic disease, stenting the bile duct is often the best treatment for pruritus. In extreme cases of pruritus that is refractory to treatment and that is causing significant negative effects on a patient’s quality of life, liver transplant can be considered.

Uremia

Pruritus from uremia is seen in patients with chronic renal failure, but rarely in those with acute renal failure. The rate of pruritus is higher in patients receiving dialysis than in those not receiving dialysis. In adults, the presence of severe uremic pruritus is a predictive factor for death.40 The mechanism by which uremia causes pruritus is not fully understood, but as in other systemic illnesses it is likely caused by the accumulation of pruritrogens in the blood.

There is very little research that has been done in the pediatric population on pruritus secondary to uremia, so the treatment options are based on the adult literature. Initial management in patients on dialysis includes enhancing the dialysis regimen and correcting the patient’s calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium. Xerosis, which is very common in uremic patients, should be aggressively treated.41 If a patient is found to have hyperparathyroidism secondary to renal failure, pruritus can sometimes completely resolve after parathyroidectomy.42 Beyond these steps, UV-B therapy has been shown to be effective, but it has potential carcinogenic side effects.43 In recent studies, gabapentin has been shown to be a helpful treatment.44 Kappa-opioid receptor agonists have shown promise, but they have not been studied in children.45 As in pruritus caused by most other systemic diseases, the only role that antihistamines play in treatment are as sedatives.

Pruritus caused by renal failure can frequently be localized. This fact may allow for the use of topical agents. There has been recent interest in the use of capsaicin cream because it has been shown to deplete substance P from C-fibers when repeatedly applied.46 Its use may be limited in young children because it causes a burning sensation for the first few days it is applied. To make capsaicin more tolerable the skin can be anesthetized with a topical anesthetic, such as eutectic mixture of local anesthetics (EMLA), before the capsaicin is applied. Other topical agents, as well as systemic medications, are being studied for the treatment of pruritus caused by uremia, but the lack of clarity about the pathogenesis of the condition makes identifying new treatments difficult.

HIV/AIDS

Pruritus is very common in patients with HIV infection. It can be secondary to multiple etiologies, including infection, infestation, peripheral neuropathy, xerosis, a primary skin condition, systemic disease, drug reaction, or elevated levels of cytokines. A thorough evaluation for the most likely causes of the pruritus should be done and should direct treatment. Idiopathic HIV pruritus is uncommon and is diagnosed by the exclusion of other causes. Phototherapy can be an effective treatment, and one study in adults suggests that indomethacin may also be helpful47 (Table 35-2).

| Cause | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Xerosis | Oil-based emollients |

| Opioid induced |

Mucositis

In 2004 the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer and the International Society for Oral Oncology published evidence-based guidelines on the treatment of cancer therapy-induced oral and gastrointestinal mucositis. These guidelines were then revised in 2006.48,49 Recommendation for the prevention of mucositis in patients receiving 5-fluorouracil, bolus doses of edatrexate, and high-dose melphalan included the use of oral cryotherapy. Unfortunately, very few recommendations about symptomatic treatment of oral mucositis could be made because of the limited evidence base. The group was able to recommend the use of patient-controlled analgesia with morphine for oral mucositis pain in those undergoing high-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Because of the paucity of evidence, clinical experience is the primary basis for treatment of mucositis.

The mainstay of treatment of oral mucositis, regardless of the cause, is the use of systemic opioids. Opioids can be very helpful, but they frequently do not completely control the pain and their use may be limited by side effects. For this reason many oral rinses have been used as adjuvant therapy. Topical agents are often mixed in different combinations and referred to by various colloquial names such as magic mouthwash. Topical agents that have been tried include anesthetics such as viscous lidocaine, and benzocaine. Anesthetics are frequently combined with other analgesic drugs such as morphine, diphenhydramine, and anti-inflammatory agents such as topical benzydamine hydrochloride, which is not FDA approved in the United States, or dexamethasone. Coating agents such as aluminum hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide containing liquid antacids are also frequently included in oral rinses. Some combination of these agents are often combined and ordered for topical use by swishing the solution around the oral cavity and then spitting it out. Caution needs to be taken when considering the use of topical anesthetics due to the theoretical concern over an increased risk of aspiration secondary to the numbing effects of the drugs and concern over systemic absorption through damaged mucosal surfaces. Topical ketamine has shown promise as an effective treatment for oral pain. In one study, topical ketamine and morphine were shown to be safe, easy to use, and effective treatments for post-tonsillectomy pain in children 3 to 12 years of age.50

The most promising therapy being investigated for the prevention and treatment of oral mucositis is low-level laser therapy. Laser therapy has trophic, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic effects. One pilot study showed that laser therapy in children with chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis resulted in decreased severity of the mucositis and marked pain relief.51 Another study showed a significant decrease in the duration of chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis in children.52

Diaper dermatosis

For persistent dermatoses that present in the diaper area, and are unresponsive to conventional treatment, dermatologic consultation along with skin biopsy might be indicated. Skin diseases such as inverse psoriasis or inverse pityriasis rosea as well as viral exanthems may present with prominent groin involvement. It is also important to exclude eruptions such as Langerhan cell histiocytosis (LCH), which generally presents as scaly papules or plaques with a predilection for intertriginous and scalp areas (Fig. 35-2).

Wounds

There are several causes for wounds that occur in children receiving palliative care. Pressure ulcers, malignant wounds, and wounds caused by blistering skin conditions are the most common. Only minimal literature is available regarding treatment of pediatric versus adult wounds, because the majority of data has focused on the compromised and elderly patient. Lack of scientific data has contributed to ongoing use of modalities that are not optimal in managing wounds in the pediatric population, including saline gauze and leaving wounds open to air so that they can breathe.8

Types of wounds

Pressure Ulcers

Pressure ulcers in the pediatric population, while not as prevalent as in adults, are still a significant dermatologic occurrence that must be appropriately addressed. The incidence of pressure ulcers in the pediatric population ranges from 20% to 43% in outpatients with spina bifida to 23% in children in neonatal intensive care.1–4 Minimal data is available on the overall incidence of pediatric pressure ulcers. The exception is a national survey of healthcare institutions5 that suggests a pressure ulcer incidence of 0.29% and a prevalence rate of 0.47%, while Dixon and Ratcliff list incidence and prevalence of pressure ulcers in pediatric patients as between 7% to 27% and 0.47% to 6.5%, respectively.6 Data on the incidence and point prevalence of pediatric pressure ulcers in different care settings, such as the home setting versus the hospital, are not available.

Pressure ulcers occur in similar locations in both adults and children. The most common locations are the heels, neck, sacrum, and scalp. Spina bifida and other diseases requiring immobilization may result in wounds over bony protrusions and popliteal areas.7

Blistering Dermatoses

When large blisters do form they may need to be aspirated without removal of the roof of the blister, which provides a natural dressing. When there are open wounds the general principles of wound care discussed in this chapter can be applied. Open wounds are often treated with an antibiotic cream and covered with a non-adherent dressing. Dressings can be held in place with stretchy tubular gauze netting (Figs. 35-3 and 35-4).

Documentation and education

Family education may be difficult as the expectations for rapid recovery and optimal outcomes may be unreasonable. Underestimation of time to closure, lack of clarity about expected outcomes and non-disclosure of treatment complications and their advantages and disadvantages may lead to frustration on the part of the patient and family. A clear, concise, compassionate explanation of the treatment and the expected outcome establishes credibility and collaboration. Risk assessment and prevention practices are outlined by various associations, organizations, and publications.9–11

Staging of pressure ulcers is the same in adult and pediatric populations. The accepted stages presented by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) are listed in Box 35-1. The description and identification listed for each stage has not been modified for the pediatric population.

Treatment

Debridement

Extensive literature discusses the importance of removing non-viable or infected tissue from a wound bed because it may delay wound closure and contribute to infection.18–20 The data is largely derived from adult literature, but the principles can be applied to the pediatric population. Unless surgical debridement is necessary due to extensive damage that is not easily addressed by conservative approaches, topical wound debridement outside the operating room may be successfully performed by application of a topical anesthetic such as EMLA followed by gentle curettage or cautious debridement with a sharp instrument. Enzymes have also been used successfully in cases where sharp or more aggressive debridement may not be possible or indicated. As with many products related to wound care, minimal data is available establishing safety and efficacy of enzymes in the pediatric population. Establishing the risk-benefit ratio and reviewing the patient medical history is imperative prior to prescription of any enzyme. No documentation is available regarding use of this drug category in neonates, therefore, application in this population cannot be recommended.

The primary enzyme available on the U.S. market is collagenase, because papain-urea products are not available. Use of medicinal honey as an antimicrobial and debridement- promoting agent has been documented for pediatric use, although not in well-designed randomized controlled and adequately powered trials. It appears to have been well tolerated and effective in the limited data presented.21

Nutrition

The adverse effects of poor nutritional status on tissue repair, infection rates, morbidity and mortality are well documented in the literature.25–27 Understanding the overall nutritional status of the pediatric patient by reviewing markers, including but not limited to albumin and pre-albumin levels, is a key component of wound healing. Despite relieving pressure, addressing the underlying wound etiology and choosing an adequate dressing, tissue repair may not occur in the absence of adequate nutrition. Including a nutritionist in the interdisciplinary team caring for the patient may be useful.

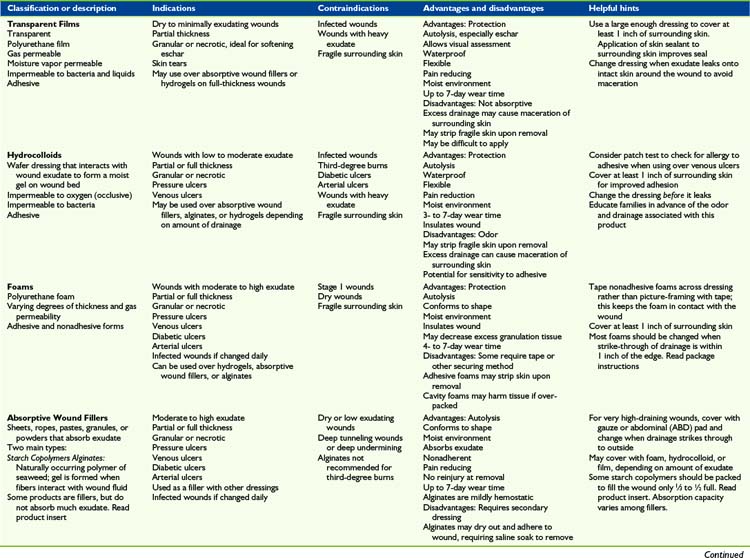

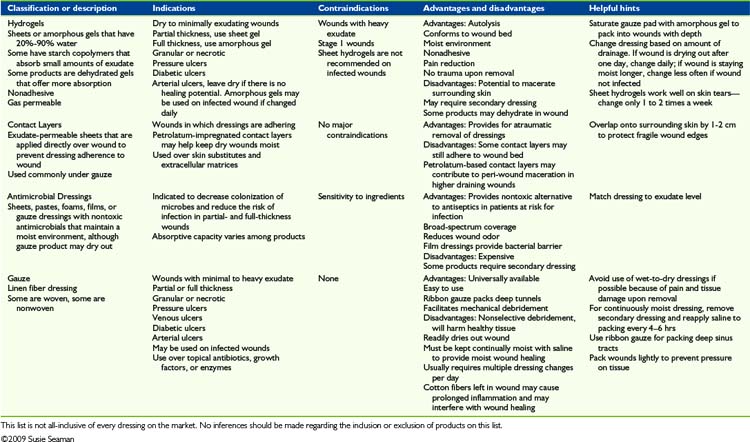

Topical therapy

Myriad topical dressings, ointments, and treatment modalities are available. The variety of products and manufacturers’ claims creates confusion rather than clarity as to which treatment is most appropriate and effective. It is important to explore in greater depth the information provided with each product, particularly indications and contra-indications, before product selection. This overview is intended to categorize each of the primary dressing types. Table 35-3 provides a concise list of advantages and disadvantages of each product in a category. The data listed are meant as a guideline since individual medical status needs and considerations will vary among patients. Similar products within each category have never been compared with each other in any published Level I or credible trial. Based on the lack of research, it may be justly assumed that the major differences between products within a dressing category are based on cost considerations, qualitative features, patient tolerance, availability, and educational support provided by the industry. Each patient’s wound requirements, medical status, tolerance to product components, reaction to adhesives, and other features should be considered before choosing a product in any category.

Silver and Antimicrobial Dressings

Silver and antimicrobial dressings are available in versions of almost all of the above products. They are also readily available topically, as in silver sulfadiazine cream. There is no Level I study or other significant data related to antimicrobial dressing use and improved outcomes in pediatric pressure ulcers. Patients with heavy colonization of a wound, high risk of wound infection, or an immunosuppressive disorder are at risk of developing a clinical infection requiring oral or systemic antibiotic therapy. Reducing or controlling the level of pathogens in a chronic wound to below a critical level in high-risk scenarios may ultimately benefit the patient. However, antimicrobial products, while not contraindicated in the presence of infection, are not meant to be used as the primary treatment for a true clinical infection. Except for in an immunocompromised individual, the host immune system may be expected to be successful at eradicating bacteria at a local level. Products with high silver content, above 2 parts per million have not been well studied in the pediatric patient and should be used with caution, particularly in the neonatal population. High concentrations of silver in clean wounds may impede new cell formation.12

Zinc is another heavy metal with antimicrobial properties. While some benefit has been suggested when applied topically,13 pediatric data is not available. There is no reason to suspect that limited use of a product with topical zinc on a superficial lesion poses any risk, yet caution is still warranted. Topical antimicrobials, including Neosporin, are commonly prescribed and are also available over the counter. Neosporin and similar agents are known to cause sensitizing reactions.14 Available data suggests they may be of benefit in reducing surface colonization, however simple daily cleansing with a liquid antimicrobial cleanser and water, followed by occlusion with gauze, is inexpensive and effective.15 A comparative study on incision and drainage of simple lesions in adults randomized to either an oral antibiotic or placebo showed no difference in outcomes, thereby suggesting that good wound cleaning is effective in preventing infection in the non-compromised patient.16

Topical gels with metronidazole offer the benefits of a hydrogel as listed above, while assisting with odor control caused by anaerobes. Other antimicrobial ointments, including mupirocin ointment, address gram-positive organisms in the wound environment. A review of the literature17 reviews differences in effectiveness and cytotoxicity levels of different topical antimicrobial agents. The data presented are from studies in the adult population and should be interpreted with caution when applied to the pediatric wound patient.

Infection control

All wounds are colonized by bacteria, fungi, and other infectious agents. It is not until the infectious agent is present in sufficient quantities that the wound is considered infected. Staphylococcus epidermis and Corynebacterium are the most common wound colonizers while Proteus, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, and Candida are the most common infectious agents. The presence of pathogens at critically colonized levels are known to delay the tissue repair process.22,23 They can also lead to purulent exudate, pain, and odor. Clinical and systemic signs of infection must be carefully reviewed to ensure the wound and peri-wound skin condition is consistent with infection. Swabs and wound cultures are most accurate when taken post debridement or following gentle cleansing with a non-antimicrobial agent. Use of antimicrobial agents may result in no growth from the culture. Unless superficial debris and contaminants have been removed, the swab culture may not be indicative of deep-tissue pathogens.24 Simple contamination may be addressed through superficial debridement and wound cleansing and may not require the use of antibiotic therapy. Antimicrobial dressings may be used with caution as previously mentioned. The larger the wound surface area, the greater the need becomes to determine risk of systemic absorption of any agent that may be incorporated into a dressing, including silver, polyhexamethybutylene, iodine, or other antimicrobial. Antibiotic selection will be based on numerous factors, including identification of pathogens, spectrum of coverage of the antibiotic, and patient tolerance.

Ancillary, Advanced, and New Technologies

Of the ancillary treatment modalities, Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT) has become one of the most commonly used. NPWT is indicated for full-thickness wounds of most etiologies, including pressure ulcers. Reading the manufacture’s recommendations for pediatric use and any available literature is a requirement before use of any of the devices. A review of the literature finds no data showing any advantage of using one manufacturer’s NPWT product over another’s. NPWT is of greatest benefit in larger defects to assist with granulation. The few studies that have been done looking at the use of NPWT in the pediatric population suggest that NPWT is safe and may assist in rapid granulation and successful wound closure.28,29 Limited availability of data does not mean that the products may not be used; rather it strongly suggests that the treating clinician review the evidence for use and contact the manufacturer for any additional information concerning safety and outcomes in the pediatric population (Table 35-4; see also Table 35-3).

| Wound characteristic | Goal of therapy | Dressing examples |

|---|---|---|

| High exudate | Exudate absorption |

Symptom Control

Pain

There is frequently significant pain associated with wounds. The pain may be constant or it may be associated only with dressing changes. When the pain is constant, an evaluation should be done for treatable factors that may be causing or contributing to the pain, such as wound infection, tissue reaction, or increased pressure, particularly that over a bony prominence. Pain associated with wounds can be either nociceptive or neuropathic. For constant pain, the principles of pain management discussed in previous chapters can be applied. This might include treatment with systemic medications including opioids and pain adjuvants. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be particularly helpful in managing wound pain, but if the goal of care is to heal the wound then it should be noted that NSAIDs may interfere with angiogenesis and delay wound healing.53

Topical treatments can also be effective in controlling wound pain. It is known that opioid receptors are not only present in the central nervous system but also in the periphery.54 Topical opioids can be placed directly on wounds to block these receptors. In case studies the use of morphine-infused IntraSite gel has been shown to be effective in controlling wound pain.55

1 Weisshaar E., et al. Itch intensity evaluated in the German Atopic Dermatitis Intervention Study (GADIS): correlations with quality of life, coping behaviour and SCORAD severity in 823 children. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88(3):234-239.

2 Stander S., et al. Clinical classification of itch: a position paper of the International Forum for the Study of Itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87(4):291-294.

3 Biro T., et al. TRP channels as novel players in the pathogenesis and therapy of itch. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772(8):1004-1021.

4 Valet M., et al. Cerebral processing of histamine-induced itch using short-term alternating temperature modulation: an FMRI study. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(2):426-433.

5 Koch J., et al. Pilot study of continuous co-infusion of morphine and naloxone in children with sickle cell pain crisis. Am J Hematol. 2008;83(9):728-731.

6 Metze D., et al. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone, an oral opiate receptor antagonist, in the treatment of pruritus in internal and dermatological diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(4):533-539.

7 Wolfhagen F.H., et al. Oral naltrexone treatment for cholestatic pruritus: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 1997;113(4):1264-1269.

8 Nakatsuka N., et al. Intravenous nalbuphine 50 microg x kg(-1) is ineffective for opioid-induced pruritus in pediatrics. Can J Anaesth. 2006;53(11):1103-1110.

9 Arck P.C., et al. Neuroimmunology of stress: skin takes center stage. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126(8):1697-1704.

10 Carel K., et al. The Atopic Dermatitis Quickscore (ADQ): validation of a new parent-administered atopic dermatitis scoring tool. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101(5):500-507.

11 Molenaar H.A., Oosting J., Jones E.A. Improved device for measuring scratching activity in patients with pruritus. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1998;36(2):220-224.

12 Rucklidge J.J., Saunders D. The efficacy of hypnosis in the treatment of pruritus in people with HIV/AIDS: a time-series analysis. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2002;50(2):149-169.

13 Rucklidge J.J., Saunders D. Hypnosis in a case of long-standing idiopathic itch. Psychosom Med. 1999;61(3):355-358.

14 Sampson R.N. Hypnotherapy in a case of pruritus and Guillain-Barre syndrome. Am J Clin Hypn. 1990;32(3):168-173.

15 Maxwell L.G., et al. The effects of a small-dose naloxone infusion on opioid-induced side effects and analgesia in children and adolescents treated with intravenous patient-controlled analgesia: a double-blind, prospective, randomized, controlled study. Anesth Analg. 2005;100(4):953-958.

16 Mashayekhi S.O., et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of morphine and morphine 6-glucuronide after oral and intravenous administration of morphine in children with cancer. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2009;30(3):99-106.

17 Flacke J.W., et al. Histamine release by four narcotics: a double-blind study in humans. Anesth Analg. 1987;66(8):723-730.

18 Hermens J.M., et al. Comparison of histamine release in human skin mast cells induced by morphine, fentanyl, and oxymorphone. Anesthesiology. 1985;62(2):124-129.

19 Rosow C.E., et al. Histamine release during morphine and fentanyl anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1982;56(2):93-96.

20 Ko M.C., et al. The role of central mu opioid receptors in opioid-induced itch in primates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310(1):169-176.

21 Ko M.C., et al. Activation of kappa-opioid receptors inhibits pruritus evoked by subcutaneous or intrathecal administration of morphine in monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305(1):173-179.

22 Aymard J.P., et al. Cimetidine for pruritus in Hodgkin’s disease. Br Med J. 1980;280(6208):151-152.

23 Zylicz Z., Smits C., Krajnik M. Paroxetine for pruritus in advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;16(2):121-124.

24 Venigalla S., Gourley G.R. Neonatal cholestasis. Semin Perinatol. 2004;28(5):348-355.

25 Muller C., et al. Treatment of pruritus in chronic liver disease with the 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor type 3 antagonist ondansetron: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind cross-over trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10(10):865-870.

26 O’Donohue J.W., et al. A controlled trial of ondansetron in the pruritus of cholestasis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(8):1041-1045.

27 Zylicz Z., et al. Paroxetine in the treatment of severe non-dermatological pruritus: a randomized, controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26(6):1105-1112.

28 Browning J., Combes B., Mayo M.J. Long-term efficacy of sertraline as a treatment for cholestatic pruritus in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(12):2736-2741.

29 Davis M.P., et al. Mirtazapine for pruritus. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(3):288-291.

30 Bachs L., et al. Comparison of rifampicin with phenobarbitone for treatment of pruritus in biliary cirrhosis. Lancet. 1989;1(8638):574-576.

31 Cynamon H.A., Andres J.M., Iafrate R.P. Rifampin relieves pruritus in children with cholestatic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(4):1013-1016.

32 El-Karaksy H., et al. Safety and efficacy of rifampicin in children with cholestatic pruritus. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74(3):279-281.

33 Ghent C.N., Bloomer J.R., Hsia Y.E. Efficacy and safety of long-term phenobarbital therapy of familial cholestasis. J Pediatr. 1978;93(1):127-132.

34 Bergasa N.V., et al. Effects of naloxone infusions in patients with the pruritus of cholestasis: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(3):161-167.

35 Bergasa N.V., et al. Open-label trial of oral nalmefene therapy for the pruritus of cholestasis. Hepatology. 1998;27(3):679-684.

36 Mansour-Ghanaei F., et al. Effect of oral naltrexone on pruritus in cholestatic patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(7):1125-1128.

37 Chang Y., Golkar L. The use of naltrexone in the management of severe generalized pruritus in biliary atresia: report of a case. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25(3):403-404.

38 Ekinci S., et al. Partial external biliary diversion for the treatment of intractable pruritus in children with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis: report of two cases. Surg Today. 2008;38(8):726-730.

39 Hollands C.M., et al. Ileal exclusion for Byler’s disease: an alternative surgical approach with promising early results for pruritus. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(2):220-224.

40 Narita I., et al. Etiology and prognostic significance of severe uremic pruritus in chronic hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006;69(9):1626-1632.

41 Morton C.A., et al. Pruritus and skin hydration during dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11(10):2031-2036.

42 Hampers C.L., et al. Disappearance of “uremic” itching after subtotal parathyroidectomy. N Engl J Med. 1968;279(13):695-697.

43 Gilchrest B.A., et al. Ultraviolet phototherapy of uremic pruritus. Long-term results and possible mechanism of action. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91(1):17-21.

44 Razeghi E., et al. Gabapentin and uremic pruritus in hemodialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2009;31(2):85-90.

45 Wikstrom B., et al. Kappa-opioid system in uremic pruritus: multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical studies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(12):3742-3747.

46 Cho Y.L., et al. Uremic pruritus: roles of parathyroid hormone and substance P. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(4):538-543.

47 Smith K.J., et al. Pruritus in HIV-1 disease: therapy with drugs which may modulate the pattern of immune dysregulation. Dermatology. 1997;195(4):353-358.

48 Rubenstein E.B., et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of cancer therapy-induced oral and gastrointestinal mucositis. Cancer. 2004;100(Suppl 9):2026-2046.

49 Barasch A., et al. Antimicrobials, mucosal coating agents, anesthetics, analgesics, and nutritional supplements for alimentary tract mucositis. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(6):528-532.

50 Canbay O., et al. Topical ketamine and morphine for post-tonsillectomy pain. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008;25(4):287-292.

51 Abramoff M.M., et al. Low-level laser therapy in the prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis in young patients. Photomed Laser Surg. 2008;26(4):393-400.

52 Kuhn A., et al. Low-level infrared laser therapy in chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis: a randomized placebo-controlled trial in children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31(1):33-37.

53 Jones M.K., et al. Inhibition of angiogenesis by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: insight into mechanisms and implications for cancer growth and ulcer healing. Nat Med. 1999;5(12):1418-1423.

54 Stein C. The control of pain in peripheral tissue by opioids. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(25):1685-1690.

55 Twillman R.K., et al. Treatment of painful skin ulcers with topical opioids. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17(4):288-292.