Chapter 8 Dermatitis (eczema)

1. What is dermatitis and why is it so important?

Dermatologists use the interchangeable terms “dermatitis” or “eczema” to refer to a specific group of inflammatory skin diseases. Dermatitis presents with pruritic, erythematous macules, papules, vesicles, or plaques with or without distinct margins. Lesions pass through acute (vesicular), subacute (scaling and crusting), and chronic (acanthotic with thick epidermis) phases. Oozing, crusting, scaling, fissuring, and lichenification frequently accompany the primary lesions. Up to 25% of all patients presenting with a new skin disease have a form of dermatitis. Patients typically suffer from intense pruritus that distracts them from their daily activities, including sleep, and they are desperate for relief.

2. What is atopy?

Atopy is derived from the Greek word atopos, meaning “out-of-place,” and refers to the predisposition to develop dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. The surfaces where the body contacts the external environment are “overreactive” (the lower airways in asthma, the upper airways and conjunctiva in allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and the skin in atopic dermatitis).

3. Why is atopic dermatitis becoming more common?

The prevalence of atopic dermatitis in six- and seven-year-old children varies from less than 2% in Iran and China to 10% to 20% in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and Scandinavia. The incidence was only 2% in those born before 1960. The increase over time and difference between more- and less-developed nations has been explained by the “hygiene hypothesis.” This postulates that a reduction in the frequency of childhood infections results in an increased incidence of various allergic and autoimmune diseases including atopic dermatitis, asthma, allergic rhinitis, childhood insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and Crohn’s disease.

4. What are the diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis?

5. What is the underlying defect in patients with atopic dermatitis?

At least 50% of patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis have a defect in the gene coding for filaggrin, a protein essential to maintaining the barrier function of the stratum corneum. The stratum corneum then allows various irritants, microbes, or allergens to penetrate the skin surface, elicit cytokine release from keratinocytes, and initiate a Th2 immune response acutely that leads to the clinical manifestations of disease and increased IgE levels. In chronic cases of atopic dermatitis, the Th2 response is replaced by a Th1 response. A primary immune defect, at least in some atopic patients, cannot yet be ruled out because bone marrow stem cell transplants from atopic patients have transferred atopic dermatitis to recipients.

7. Why does atopic dermatitis itch?

Neural and chemical mechanisms are involved. When the epidermis and its nerve fibers are stripped from skin, pruritus is abolished. Keratinocytes and mast cells release high levels of nerve growth factor (NGF), which increases the sensitivity of cutaneous pruritus receptors. These sensitized nerve endings demonstrate an increased capacity to transmit signals that are perceived as pruritus (allokinesis). Chemical mediators associated with itch include serine proteases, interleukins 2 and 31, opioids, acetylcholine, prostanoids, and substance P. Histamine may play a limited role in the pruritus of atopic dermatitis. These mediators act either on nerve endings or directly on keratinocytes. They are produced by mast cells, keratinocytes, T cells, and nerve fibers.

8. Why do people like to scratch an itch?

Scratching suppresses areas of the brain associated with negative experiences of pruritus and activates pleasure centers of the brain. In other words, there is an emotional reward for scratching. Unfortunately, scratching damages the skin and worsens dermatitis so that it itches even more. Therefore, people scratch even more and get caught in an “itch-scratch cycle” that they cannot exit without medical help or supreme levels of self-restraint.

9. Does psychological stress worsen atopic dermatitis?

Probably. In mice, various stressors can produce atopic dermatitis skin lesions, possibly due to an upregulation of substance P–sensitive nerve fibers. Transepidermal water loss increases in humans who are under mental stress compared to control subjects. Such water loss is an indicator of a defective epidermal barrier.

10. Did John Phillip Sousa write the “Atopic March?”

No, but if he did, it would have a lot of scratching, sneezing, and wheezing coming from the percussion section! The atopic march is not music but the subsequent development of allergic rhinitis (70%) and/or asthma (50%) in patients with atopic dermatitis. Filaggrin mutations predispose to airway disease in atopic dermatitis patients. Evidence points to the necessity of epicutaneous exposure to allergens (e.g., dust mites) that cause allergic airway disease in these patients. If infants with atopic dermatitis have good barrier protection, it is likely that the airway disease of the atopic march can be prevented!

11. How does atopic dermatitis present at different ages?

Atopic dermatitis may present at any age, but 60% of patients experience their first outbreak by their first birthday, and 90% by their fifth. Four clinical phases are recognized:

1. Infantile (2 months to 2 years)

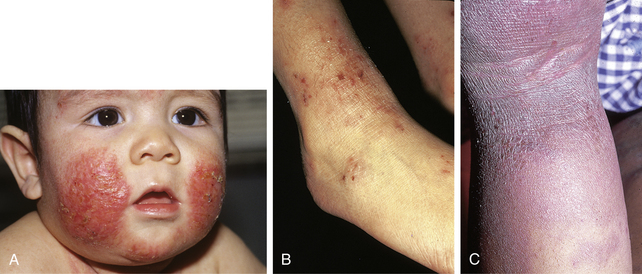

• Distribution: Cheeks (Fig. 8-1A), face and scalp, extensor surfaces of extremities and trunk (due to friction from crawling)

2. Childhood (3 to 11 years)

• Distribution: Wrists, ankles, backs of the thighs, buttocks, and antecubital and popliteal fossae (Fig. 8-1B)

4. Adult (>20 years)—50% of all patients will have recurrences as adults

• Distribution: Most commonly involves the hands, sometimes the face and neck, and rarely diffuse areas

• Morphology: Lichenified plaques, fissures on the hands, occasional vesicular outbreaks, one subset of “sensitive skin” patients

Key Points: Dermatitis

2. Moisturization (especially with ceramide- or glycerin-containing products) and topical corticosteroids remain the mainstay of atopic dermatitis treatment.

12. What physical findings are associated with atopic dermatitis?

• Keratosis pilaris: Horny plugs in follicular orifices, especially on dorsal arms, anterior thighs, buttocks, and upper back

13. What factors provoke or exacerbate atopic dermatitis?

14. How can your atopic patients relieve their pruritic agony and discomfort?

• Avoid provoking factors (scrubbing, bathing >10 minutes, hot water bathing, scented soaps, irritating clothing, low humidity, temperature extremes, copious sweating, etc.).

• Moisturize by hydrating the skin and then applying moisturizers within 3 minutes of bathing to prevent evaporation. Moisturizers containing ceramide, such as CeraVe, or glycerin, such as Vaseline Intensive Rescue products, are especially beneficial in atopic patients. Alpha-hydroxy acid products often sting and burn in dermatitis patients.

• Wear 100% cotton clothing as much as possible, and if the arms and forearms are affected during dry seasons, wear long-sleeved shirts to reduce evaporation from the skin.

• Twice-daily use or corticosteroids is only minimally more effective than once-daily use, but application in the evening is more effective than application in the morning!

• Younger patients require less potent steroids than older patients. Use occlusive vehicles (ointments, emollient creams) on dry and/or exposed lesions; use nonocclusive vehicles (creams, lotions, foams, liquids) on moist or occluded areas. Foams have the highest level of patient compliance among all vehicles.

• For acutely inflamed and weeping skin, use wet-to-dry compresses (see “Two-Pajama Treatment”) because they are soothing, antipruritic, cleansing, hydrating, and cooling. Use a topical corticosteroid with this for improved effectiveness.

• A new class of topical agents, calcineurin inhibitors, includes tacrolimus and pimecrolimus and can be safely used by following the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines.

• If lesions are secondarily infected, antibiotic therapy for 2 weeks should be prescribed. Antibiotics should not be used if clinical infection is not present.

16. Describe the “two-pajamas treatment.”

18. What is pompholyx?

Pompholyx, from the Greek word for “bubble,” accounts for up to 20% of hand dermatitis cases. It also has been called dyshidrotic eczema, even though no definite relationship to sweating has been demonstrated. Patients develop crops of clear, deep-seated, tapioca-like vesicles on the palms and sides of the fingers in 80% of cases (Fig. 8-2). Another 10% also have sole involvement, whereas the remaining 10% have only sole involvement. Erythema is often absent, and heat and prickling sensations may precede attacks. Nails may become dystrophic. The cause is unknown, but it may be a manifestation of atopic dermatitis and is exacerbated by stress in many patients.

19. How can pompholyx be managed?

Most attacks resolve spontaneously within 1 to 3 weeks. However, because pompholyx is generally symptomatic, certain measures should be tried. Hand protection, aluminum subacetate (Burow’s solution) soaks for debridement when oozing, and bland emollients help. Large blisters can be drained (and this rapidly relieves itching). Potent topical corticosteroids can be used with or without occlusion for moderate or severe acute disease. Soaking hands in warm water for 15 minutes before applying superpotent steroids and then applying white, cotton gloves overnight is especially helpful. Occasionally, oral or intramuscular corticosteroids are required to bring relief to patients. Oral methotrexate can be used in severe cases as a steroid-sparing agent. Keratolytics, tar, UVB light, or even PUVA can help chronic and/or hyperkeratotic disease.

20. Describe the typical presentation of nummular eczema.

Typically, patients are men 55 to 65 years old who report the rapid onset of tiny papules and juicy vesicles that form erythematous, 1- to 10-cm diameter, coin-shaped (i.e., nummular) plaques studded by pinpoint vesicles and erosions on a background of dry skin (Fig. 8-3). Plaques sometimes clear centrally and resemble tinea corporis. They are found most commonly on the extensor surfaces of the lower extremities, are often bilaterally symmetrical, may recur at sites of previous involvement, and are intensely pruritic. The upper extremities and trunk are involved less frequently. When the trunk is involved, only the back is usually affected.

21. What causes nummular eczema?

Nobody knows for sure, but it is probably a form of irritant dermatitis combined with very dry skin. It is rarely seen in humid environments. Up to 95% of patients have S. aureus–colonizing or -infecting lesions, which supports the idea that nummular eczema may be a hypersensitivity reaction to bacteria.

22. Is there a cure for nummular eczema?

No, but the disease can be controlled. Limiting baths and soap exposure, avoiding irritants, frequent use of moisturizers, topical corticosteroids, and avoiding dry environments all have a role in treatment. Topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy. With the high rate of staphylococcal colonization, many dermatologists routinely prescribe a 2-week course of oral antibiotics such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, dicloxacillin, or cephalexin. I find 1 mg/kg triamcinolone acetonide mixed with 0.1 mg/kg Celestone intramuscularly particularly helpful, and it causes far fewer side effects than oral steroids that may also be used in severe cases, limited to a tapered 2 to 3 week course. Severe chronic cases may also benefit from PUVA.

23. How does seborrheic dermatitis present in children?

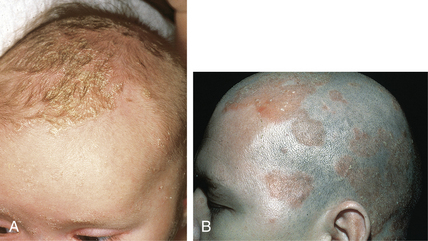

Retention hyperkeratosis of the scalp known as “cradle cap” (Fig. 8-4A) is the most common presentation, while “napkin dermatitis” in the diaper area is the next most frequent. The primary lesions are round to oval patches of dry scales or yellowish-brown, greasy crusts with variable erythema. Seborrheic dermatitis presents in infants 2 to 10 weeks of age and generally clears by 8 to 12 months of age before reappearing at puberty. However, there are exceptions, and children of all ages may have this condition, even though they do not produce sebum as much as adults do.

24. How does seborrheic dermatitis present in adults?

Dandruff—visible scalp desquamation—is the precursor lesion. The scalp may become inflamed and covered with greasy scale (Fig. 8-4B). Dull or yellowish-red, sharply marginated, nonpruritic lesions, covered with greasy scales are seen in areas with a rich supply of sebaceous glands. Characteristically, the medial eyebrows, glabella, melolabial folds, nasofacial sulci, and eyelid margins (blepharitis) are involved. Preauricular cheeks, postauricular sulci, and external auditory canal lesions are also commonly affected sites. The trunk may demonstrate presternal or interscapular involvement. Intertriginous areas, such the inframammary creases, umbilicus, and genitocrural folds, are occasionally involved. Seborrheic dermatitis is one of the most common causes of chronic dermatitis of the anogenital area.

25. What causes seborrheic dermatitis, and with what disease states is it commonly found?

Current theories suggest that immune hyperreaction to the commensal lipophilic yeast Malassezia (that lives in our sebaceous glands) and/or sebum causes the dermatitis. An increased incidence and severity of seborrheic dermatitis are seen in persons with central nervous system (CNS) diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, facial paralysis, poliomyelitis, syringomyelia, and quadriplegia. The CNS may stimulate increased rates of sebum production. HIV-infected individuals also frequently demonstrate severe seborrheic dermatitis.

26. Discuss the treatment approaches to seborrheic dermatitis.

• Wash hair and scalp daily with anti-Malassezia shampoos containing ketoconazole (best combination of price and effectiveness), selenium sulfide, or zinc pyrithione.

• For scalp with moderate scale, use shampoos containing keratolytics, such as tar, salicylic acid, or sulfur to debride scale.

• For extremely thick scalp scale, massage Baker’s P&S Liquid or Derma-Smoothe F/S oil into the scalp at bedtime and remove by shampooing in the morning.

27. What is an “id” reaction, and what does it have to do with Sigmund Freud?

An id reaction, also known as autosensitization dermatitis, is an immunologically mediated cutaneous inflammation in the absence of locally viable organisms or other locally inciting cause. It presents suddenly as an acute, monomorphous, papulovesicular dermatitis distant to an area of primary dermatitis. It usually erupts symmetrically on the hands, forearms, flexor aspects of the arms, extensor aspects of the arms and thighs, and, less commonly, on the face and trunk. Juicy papules often coalesce into small plaques with associated red macules or wheals. Sigmund Freud did not discover id reactions. In dermatologic usage, “id” derives from a Greek suffix for a father–son relationship or resemblance. Freud’s id derives from a third-person Latin pronoun.

28. What are the most common settings for an id reaction and how should you treat it?

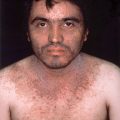

Stasis dermatitis, scabies, and dermatophyte infections (Fig. 8-5) are the most common settings. The distant lesions often take on the characteristics of the primary cutaneous lesions. The cure lies in treating the primary lesion because, by definition, an id reaction resolves when the primary dermatitis departs. Many id reactions require symptomatic treatment with antipruritics, wet-to-dry soaks, and topical corticosteroids. Often, systemic corticosteroids are necessary to bring relief.

30. How can you determine the cause of a patient’s exfoliative dermatitis?

31. What general treatment measures are used to treat patients with exfoliative dermatitis?

• Wet-to-dry dressings with desonide 0.05% ointment, a mild topical corticosteroid, reliably, significantly, and rapidly improves almost any case of exfoliative dermatitis.

• Problems arising from the erythema and exfoliation such as dehydration, high-output heart failure, and hypothermia must be treated empirically.

Figure 8-2. Pompholyx. Characteristic “tapioca” or “sago-grain” vesicles on the sides of the fingers.

(Courtesy of Fitzsimons Army Medical Center.)