CHAPTER 6 Depressive disorders

We all know what it means to feel sad and unhappy, and in English we often use the term ‘depression’ to describe that experience. We use this term to describe many states in which there are features which include unhappy mood but which also involve disruption of other functions such as thinking, self-esteem, sleep, perception of energy, sexual interest, appetite, the experience of pleasure generally and the ability to interact with other people. Depressive disorders are more common in women (lifetime prevalence about 11%) than men (lifetime prevalence about 6%). A summary of the diagnostic criteria for depressive disorders for DSM–IVTR and ICD–10 is presented in Table 6.1.

TABLE 6.1 Features of a depressive episode in adults according to DSM–IVTR and ICD–10

| DSM–IVTR (synopsis) Major depressive episode | ICD–10 (synopsis) Depressive episode |

|---|---|

| Five (or more) of the following symptoms (must include either (1) or (2)) on most days, for most of the day, over at least 2 weeks, associated with distress and impairment of functioning:

(9) recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation, or suicidal plan

Exclusions: |

Classification into mild, moderate or severe depression is determined by the number of items below which can be identified:

(1) depressed mood to a degree that is definitely abnormal for the individual, present for most of the day and almost every day, largely uninfluenced by circumstances, and sustained for at least 2 weeks

An additional symptom or symptoms from the following list should be present to give a total of at least four: |

Clinical features of depressive disorders

Changes in mood

These are predominantly an experience of emptiness rather than sadness (see Box 6.1). There is little or no capacity for the experience of pleasure (‘anhedonia’), a core feature of depressive disorders. The unpleasant mood tends to be present almost constantly, often with an exacerbation in the mornings and improvement in the evenings (‘diurnal mood variation’) and is associated with the ‘melancholic’ or ‘somatic’ subtype of depressive disorder (see Box 6.2). (Diurnal mood variation may also be evident during times of high emotional stress and is not a pathognomonic feature of depressive disorder.) Mood in depressive disorders tends to exhibit poor response to events or circumstances (loss of ‘reactivity’ of mood). Unpleasant arousal (anxiety) and anger are sometimes prominent.

Changes in thinking

Depressive disorders have an effect upon thought content and are often provoked by persistently negative and self-defeating patterns of thought about the self, the past and/or the future. Poor self-esteem is often prominent among these. Excessive guilt about actual or even imagined wrongdoings may develop and suicidal thoughts are common. The capacity to think may be significantly impaired (e.g. concentration, memory and comprehension) and executive cognitive functions (e.g. decision making, abstract thinking, changing set and problem solving) may also be affected. Severe impairment of thought function and physical spontaneity is called ‘psychomotor retardation’.

Psychotic depression

Hallucinations may occur and are often auditory in form. For example, the person may hear a voice making critical and disparaging remarks about them, in either the second or third person. Sometimes, the sufferer may experience olfactory hallucinations of their body emitting a foul odour (perhaps as it is perceived to decay). Psychotic depression is a particularly severe and destructive form of depressive illness and carries a high mortality rate from suicide.

Less ‘typical’ presentations

Not all people who suffer depressive disorders present initially with the features outlined above. This less typical presentation is called atypical depression (see Box 6.3) and may have implications for choice of treatment. Some notes regarding groups of patients with special elements in their depressive disorders are listed in Box 6.4.

BOX 6.4 Special groups and settings

Natural history of depression

Most depressive disorders arise slowly (bipolar depression is often an exception; see Ch 7) and have been present for some time before a person presents for assistance. The earliest reported symptoms are often changes in sleep or energy, with other features accumulating over time. If left untreated, depressive disorders may improve spontaneously, but this may take months to years and the risk of suicide is significant. Many individuals will not improve spontaneously and remain depressed for the rest of their lives, usually with some fluctuations in severity. The toll of depressive illness upon the sufferer is enormous and the consequences may include loss of relationships, careers, general health, loss of brain tissue, as well as suicide. Those close to a person with a depressive disorder also suffer and are often forgotten.

Differential diagnoses

Grief is an entirely healthy response to loss and will include experience of sadness for that which has been lost. The experience of grief and its expression (mourning) is variable and will be determined by personality, past life experience, current life context, cultural traditions and expectations, and the nature of the loss. The experience may include absence of emotion (‘numbing’ or ‘detachment’), overwhelming distress, anger, denial of the loss and/or preoccupation with the lost object (see Box 6.5). Auditory, visual and even other modalities of hallucinations may occur, are mostly reassuring and positive, and are not pathological in nature. Sometimes, the individual is unable to integrate the loss constructively into their experience of life (pathological grief) and transitions into depressive disorder.

Grief and other distressing reactions to unpleasant life circumstances which interfere with function but do not meet criteria for a depressive disorder are diagnosed as adjustment disorders, further specified by the predominant symptoms (e.g. with depressed or anxious mood). Schizophrenia is often accompanied by depressive disorder and negative symptoms of schizophrenia may be confused with depressive disorder (see Ch 5).

A number of general medical disorders can provoke depressed mood (see Box 6.6), but the depression may persist after these have been treated. The sufferer may present with emotionally focused depressive symptoms such as persistently depressed mood or anhedonia, or less specific symptoms such as insomnia, anergia or weight loss. The contribution of depressive illness to these symptoms may be significant and treatment of the depressive illness may bring significant improvement. However, usually the symptoms are mixed in origin and the outcome will be optimal when both the medical condition and depressive disorder are treated. Indeed, each will usually affect the other and treating both will give the best outcome.

BOX 6.6 General medical conditions sometimes associated with depressive disorders (an incomplete list)

CASE EXAMPLES: depressive disorder

A 45-year-old medical practitioner presented saying she felt stupid coming for such a silly reason but she had been finding that she was struggling to take an interest in her patients, was sleeping poorly and lacked energy. She thought she might be depressed, but had always thought that her knowledge of medicine should enable her to cope with depression by herself. After some brief supportive psychotherapy, she responded to an antidepressant and cognitive behaviour therapy.

Aetiology of depressive disorders

Neuroimaging

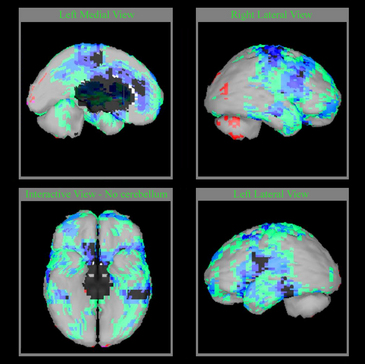

In chronic depression, the hippocampus is often reduced in size (perhaps because of reduced neurotrophic factor release) and other regions may show similar changes. In later age, small areas of brain injury associated with hyperintensity on magnetic resonance image (MRI) scanning appear correlated with the severity of depressive disorder. Figure 6.1shows computer-generated images of a single photon emission computerised tomography (SPECT) scan of a patient with a depressive disorder.

Neurochemistry

Amines

Among the hundreds of neurotransmitters in the human brain, the amines serotonin, noradrenaline and dopamine (see Box 6.7) appear particularly important in depressive disorders. This conclusion has followed a series of observations, including the propensity of certain drugs to provoke depression, altered physiological responses to certain drugs, measurements of metabolites of these amines in depressed people, and the observation that substances which relieve depressive symptoms enhance the release of these amines. Importantly, all of the currently available antidepressant medications have significant effects upon the biogenic amines, emphasising their important role in depressive disorders.

Sleep

Sleep process is usually disturbed in depressive illness, with increased duration of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, increased eye movement during REM periods (REM density), reduced deep sleep (stages 3 and 4) and significant changes in total sleep duration (mostly reduced and sometimes increased). Further, it is known that disruption of circadian rhythms may aggravate depressive disorder.

Management of depression

The management of the depressed patient requires a comprehensive assessment, engagement, and a treatment plan that addresses biological and psychosocial domains (see Box 6.8).

Basic clinical strategies and challenges

The management of a person with depressive illness begins with the process of assessment, which becomes potentially therapeutic (supportive psychotherapy) because the person has an opportunity to experience hope, to experience feeling understood and supported, and to release painful emotions and thought content.

Psychological therapies

Behaviour therapy addresses the behaviours which contribute to the depressed state, including lack of exercise, lack of pleasurable activities, avoidance of contact with significant others and absence of self-care. In practice, this is often linked with cognitive therapy—so-called cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT).

Biological therapies

While some people suffering from depressive disorders will respond to psychological therapies alone, some will not. Biological therapies are most effective when used for depressive disorders of at least moderate severity and when somatic or melancholic features are evident. Some form of psychotherapy remains essential, as antidepressants will not change styles of thinking, relationships or the management of life problems. However, antidepressant medications will facilitate cognitive and emotional functioning, restoration of energy, drive and motivation, and the recovery of basic biological functions such as appetite, sex drive, mobility, cognitive functions and self-care. For more on biological therapies, see Chapter 13.

Antidepressant medications

These medications facilitate recovery of the biological elements of depressive disorders by modifying levels of amines in the brain and subsequently enhancing release of nerve growth factors. They are effective in about 60–70% of people who suffer more than mildly severe depression. Treatment with these medications should be for at least 6 months and often longer, including indefinitely in some patients (see Ch 13).

Adjunctive medications and treatments

Folic acid deficiency is destructive to mental state, and supplements may be essential if deficiency is evident.

Magnesium and zinc deficiency is destructive to mental state, and supplements may be appropriate.

For more on adjunctive medications and treatments, see Chapter 13.

References and further reading

Castle D., Kulkarni J., Abel K., editors. Mood and anxiety disorders in women. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Iosifescu D., Nierenberg A., editors. New developments in depression research. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2007.

Joyce P., Mitchell P., editors. Mood disorders recognition and treatment. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2004.

Parker G. Melancholia: a disorder of movement and mood. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996.

Parker G., Manicavasagar V. Modelling and managing the depressive disorders. A clinical guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Tanner S., Ball J. Beating the blues. Sydney: Southwood Press; 1991.