Chapter 12 Depression

Introduction

Mental health is closely linked to physical health. Depression (e.g. major depression) is highly prevalent and a major cause of disability. The World Health Organization (WHO) expects that by 2020 depression will rank second only to ischemic heart disease in terms of disability, irrespective of gender and age.1 Currently, depression is ranked as the second cause of disability in terms of disability adjusted life years in the age category 15–44 years for both genders combined.1 Depression is a common illness affecting at least 1 in 5 people during their lifetime.2 Depression has no gender, age, or lifestyle background predilection, it can potentially occur in all persons. Depression facts:

Patients often present with an overlapping and complex set of symptoms (Table 12.1).

| Physical symptoms | Emotional symptoms |

|---|---|

| Tiredness and fatigue | Sadness and tearfulness |

| Sleep disturbances | Anxiety and irritability |

| Headaches | Loss of interest |

| Gastrointestinal disturbances | Hopelessness |

| Psychomotor activity changes | Difficulty concentrating |

| Appetite changes | Guilt |

| Body aches and pains | Suicidal tendency |

Depression also influences the morbidity and mortality of a number of somatic illnesses. Research strongly documents a significantly higher risk and mortality in depressed patients post acute myocardial infarction.4 There is also evidence demonstrating that depression is significantly associated with diabetics.5

Complementary medicine (CM) encompasses a wide range of therapies that are currently not part of conventional medicine and are often adopted by patients who feel the need to take more control over their illnesses. Unfortunately, this often leads to patients self-medicating to alleviate symptoms, such as emotional distress, to help them cope with serious mental illness problems.6

A recent review7 has reported that systematic trials are required for promising substances for depression and that meanwhile, those patients wishing to take psychotropic complementary medicines require appropriate medical advice. In this chapter we review the evidence-based research in CM approaches to the treatment of depression, that includes the use of herbal medicines, nutritional and dietary supplements, mind–body medicine approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), meditation, hypnosis, aromatherapy, acupuncture and light therapy.

A recent review of the literature identified a range of possible non-drug treatments for the treatment of depression in the elderly.8 The review found best evidence for antidepressants, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), CBT, psychodynamic psychotherapy, reminiscence therapy, problem-solving therapy, bibliotherapy and physical exercise. Limited evidence was identified for transcranial magnetic stimulation, dialectical behaviour therapy, interpersonal therapy, light therapy, St John’s wort and folate.

Another review of the literature found the best evidence for the treatment of depression occurred with St John’s wort, exercise, bibliotherapy, CBT and light therapy (for winter depression), and promising evidence (but needing more research) for folate vitamin E, vitamin B6, vitamin D, SAMe (s-adenosyl methionine), phenyalanine, Ginkgo biloba, acupuncture, light therapy (non-seasonal depression), massage therapy, negative air ionisation (for winter depression), relaxation therapy, yoga, and reducing or avoiding alcohol, sugar and caffeine avoidance and possibly music/dance therapy.9

Healthy lifestyle changes

In the management of depression, emphasis on lifestyle changes is vital, such as stress management, improved diet, sleep, exercise, sunlight exposure and smoking cessation. The treatment of depression requires the health practitioner to spend long consultations exploring all of these areas.10 A few words of advice can go a long way towards changing patients’ health behaviour.11 A study found that patients were more likely to try to quit smoking, change their diet and perform more exercise when written information leaflets were backed by encouragement and GP advice. The study also concluded that advice on health behaviour may have to be delivered several times before it brought about change.11

Mind–body medicine

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), group therapy and support groups

Counselling and CBT carry the greatest weight of scientific evidence for the treatment of depression.12 The types of psychotherapy that have proven efficacy are mainly CBT and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT).13, 14

A recent study with depressed mothers demonstrated that brief IPT was beneficial in reducing levels of maternal symptoms of depression and improving functioning at the 3– and 9–month follow-ups compared to usual treatment for depression.12 Moreover, the meta-analysis reported that preventative strategies such as IPT may be more effective than prevention based on CBT.13

The health practitioner needs to be alert to stressors the patient is experiencing in the school, home or work environments. Traumatic and stressful experiences in people’s lives such as relationship breakdowns, loss, bullying, being excluded by peers, experiencing humiliation, life-threatening events, assault (physical and sexual), and loss of work are potent triggers for depression and feelings of suicidal ideation.15–19

The prognosis of depression is worse when the patient has a serious illness such as cancer or heart disease.20, 21

CBT is at least as effective as antidepressants in outpatients with severe depression according to a meta-analysis of 4 major randomised trials.22

Recent reviews23,24 conclude that psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy generally are of comparable efficacy, and both modalities are superior to usual care in treating depression.

CBT has been investigated in a number of clinical scenarios, and demonstrated better efficacy than medication for post-partum depression.25 CBT was efficacious in reducing depressive symptoms among HIV-infected individuals,26 was effective for the treatment of unipolar depression,27 effective in incurable cancer patients,28 and a recent meta-analysis suggests that CBT may be of potential benefit in older people with depression.29 Further, recently it has been reported that CBT may be useful for depressed patients diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease.30

Young adolescents with depression and repeated self-harm showed promising results in a Group therapy program.31 UK child psychiatrists randomised 63 patients aged 12–16 to routine care or to a weekly group therapy program over 6 months. The adolescents in the group therapy program were less likely to harm themselves, less likely to use health care resources, had better school attendance, and a lower rate of behavioural disorders. However, there was no effect on the severity of the depression or its prevalence.

A comprehensive meta-analysis of the literature of 19 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), meeting the inclusion criteria, highlighted that efficacy of preventive psychological interventions can reduce the incidence of depressive disorders by 22% in experimental groups compared with control groups. Therefore, therapies such as counselling and CBT may also play a role in the prevention of depression onset.14

Stress management

A 12-week, randomised, clinical trial of 123 outpatients who met the DSM-IV criteria for major or minor depression within 1 year after coronary artery bypass surgery significantly improved following 12 weeks of CBT or supportive stress management. The CBT group led to remission of depression at 3 and 9 months in 71% of patients and 57% for those undergoing supportive stress management by 3 months compared with 33% remission in the usual care group. At 9 months remission rates were similar with CBT being far superior to usual care for depression and other secondary psychological outcomes, such as anxiety, hopelessness, stress, and quality of life.32

Meditation

Mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction programs have demonstrated effectiveness in decreasing mood disturbance, including depression and stress symptoms in patients with a wide range of types and stages of cancer.33, 34 A randomised, wait-list controlled design of 90 patients (mean age 51 years, 78% females) was used with the intervention consisting of weekly meditation of 1.5 hours for 7 weeks plus home meditation practice.33 Patients in the mindfulness meditation intervention group demonstrated significantly lower scores on total mood disturbance by 65% and sub-scales of depression, anxiety, anger and confusion compared with control participants. The treatment group demonstrated less stress symptoms (by 31%), fewer cardiopulmonary and gastrointestinal symptoms, and less emotional irritability and cognitive disturbances. A recent preliminary study investigating mindfulness-based stress reduction reported that participation in the program was associated with enhanced quality of life and decreased stress symptoms, altered cortisol and immune patterns consistent with less stress and mood disturbance, and decreased blood pressure.34

Relaxation therapy

A recent Cochrane review and meta-analysis of 15 trials with 11 included in the analysis demonstrated that relaxation was effective for reducing depressive symptoms.35 Five trials showed relaxation reduced self-reported depression compared to wait-list, no treatment, or minimal treatment post-intervention (SMD −0.59 [95% confidence interval [CI] −0.94 to −0.24]). For clinician-rated depression, 2 trials showed a non-significant difference in the same direction (SMD −1.35 [95% CI −3.06 to 0.37]). A recent assessment of the Cochrane review concluded relaxation techniques were better than either wait-list, no treatment or minimal treatment, but not as effective as psychological therapies such as CBT.36

Music therapy

A recent Cochrane review identified 4 studies that reported greater reduction in symptoms of depression among those randomised to music therapy than to those in standard care conditions.37 A fifth study showed no benefit. Overall there were low dropout rates from music therapy. The Cochrane review reported that music therapy was accepted by people with depression and was associated with improvements in mood.37 However, the review cited that the trials reviewed were small in number and that they had low methodological quality. Hence, it was not possible to be confident about the effectiveness of music therapy in the treatment of depression. High quality trials evaluating the effects of music therapy on depression are thus required.

Religion and spiritual health

Healthy religious beliefs may assist older patients with depression after a medical illness by providing comfort, support and improved coping strategies to help them manage, according to a US study.38 In the study, 94 patients aged 60 and older diagnosed with depression during a hospital admission for a physical complaint, were more likely to recover from depression if they had expressed religious beliefs. In a further US study,39 with data from 2600 male and female twins, has reported a strong association between religious beliefs and a lower intake of alcohol, nicotine and drug dependence or abuse, with less effects on depression. However, in a recent study 503 patients participating in the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) trial completed a Daily Spiritual Experiences (DSE) questionnaire within 28 days from the time of their acute myocardial infarction (AMI). The results showed little evidence that self-reported spirituality, frequency of church attendance, or frequency of prayer is associated with cardiac morbidity or all-cause mortality post-AMI in patients with depression and/or low perceived support.40

Health practitioners require awareness of the potential role of spirituality, religiosity and depression.41 This field of evidence is important so as to provide a more holistic approach to psychotherapy treatment.41 Whilst many studies link a lack of religiosity to depression, one important factor is that it may be a lack of meaning and spiritual fulfilment that is part of the increasingly secular and materialistic society contributing to the increased incidence of depression in the Western countries.

A US study42 of 160 terminally ill cancer patients in a catholic palliative care hospital found that spiritual wellbeing offered some protection against end-of-life despair and depression. The study demonstrated the importance of spiritual wellbeing in reducing psychological distress, in particular in palliative care practice.

Family support

An Australian study with terminally ill patients in a catholic hospice reported that family support was correlated with no documented requests for euthanasia, a surrogate marker for possible enhanced depressive dispositions.43

Early studies that include a review of the literature have indicated that a healthy marriage is beneficial for both mental (especially depression) and physical health.44 Also that a healthy marriage is equally protective for both men and women.45

Sleep disturbance

Whilst sleep disturbance is common in patients with depression, there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that sleep deprivation may be a contributor to depression.46, 47

In an Australian Melbourne study, 86 patients aged 16–88 years (average age = 42 years; female participants = 54%) presented as suffering from chronic insomnia, of which two-thirds were also suffering from depression.48 Participants were then introduced to a self-help program (a book and 3 audiocassettes), and a manual to assist in non-drug approaches to sleep, which they used at home to improve their sleep. At follow-up, 6–8 weeks later, 70% of the insomnia sufferers who were depressed before treatment and learned to sleep better were no longer depressed, or were significantly less depressed, once their sleep had improved. An additional 13%, while still depressed, had a reduction of at least 40% in their depression scores. By contrast, among people who did not learn to sleep better, none experienced a significant reduction in depression. This study strongly suggests that, for many people who suffer from both depression and insomnia, treating the insomnia successfully without medication may eliminate or significantly reduce their depression. Further, just over half of those participants who were using antidepressant medications at the initial interview had ceased using it by follow-up, were sleeping significantly better, and were no longer depressed. Whilst the findings of this research are quite impressive, more research in this area is required.

Another Australian Melbourne study at the Royal Children’s Hospital using a screening questionnaire of 738 mothers with infants 6–12 months of age, also suggested that sleep deprivation was a contributor to post-natal depression (PND).49 If the mother reported a problem with their child’s sleep, they were twice as likely to score the PND threshold than mothers who did not report a problem. Mothers reporting good sleep, despite an infant sleep problem, were not more likely to develop depression. A further study by the same group demonstrated that by treating the mothers’ sleep using behavioural interventions, the depression score was reduced significantly as reported in a randomised control trial of 156 mothers with infants aged 6–12 months.50 This benefit was sustained at 2 months and at 4 months for mothers with high depression scores.

A sample study of 5692 US adults, found those who reported sleeping difficulties such as initiating or maintaining sleep and early morning awakening, was associated with a two-fold increase risk of suicidality than participants without sleep disturbance.51 Chronic sleep problems were found to be an independent risk factor for depression and suicidality, so it would appear addressing sleep problems could play an important role in prevention of depression and suicidality.

A recent interventional study reported that a sleep intervention program implemented in infancy resulted in sustained positive effects on maternal depression symptoms and found no evidence of longer-term adverse effects on either the mothers’ parenting practices or the children’s mental health.52 This intervention demonstrated the capacity of a functioning primary care system to deliver an effective and universally offered secondary prevention program.

Adequate sleep is essential for general health. A study has found that sleep deprivation combined with light therapy was useful in the treatment of drug resistant bipolar depression.53 The response was effective for acute and long-term remission rates. (See Chapter 22 on insomnia and sleep disorders.)

Sunshine

Vitamin D

Sunshine is the main source of vitamin D produced by the body in response to direct skin exposure to UVB. This means that no or minimal exposure to sun can contribute to vitamin D deficiency as seen in community groups with dress codes (e.g. wearing veils), living in geographical prone areas (e.g. in high and low altitudes) especially over winter, working indoors (e.g. office work), institutionalisation, prolonged hospitalisation and bed-bound people, and particularly in dark skin people who need longer sun exposure.54, 55 Vitamin D deficiency especially over winter with lower sun exposure is linked with lower moods, depression and seasonal affective disorder. Increasing sun exposure and supplementation with vitamin D3 can improve moods.56, 57

Light therapy

Light therapy is a physical intervention that is used to treat depression and depressive disorders such as bipolar.53 Cognitive decline, mood, behavioural and sleep disturbances, and limitations of activities of daily living commonly burden patients, especially the elderly with cognitive deficits.58 Circadian rhythm disturbances have been associated with these symptoms.58 Light therapy exposes patients to a bank of bright lights for a variable number of hours per day, usually 1–3 hours. Patients can engage in activities during the period of exposure, such as reading and computer use or relaxation time. In a recent study that reviewed CM therapies in the treatment of depression in children and adolescents, Jorm and colleagues59 have described good evidence for the efficacy of light therapy in winter depression. There was, however, no evidence that it would be effective for non-seasonal depression.

Studies suggest that light therapy may be beneficial when used as an adjunct with other treatments.60, 61 Results from 1 study indicate that there was a positive total sleep deprivation response in major depression patients which can be predicative of beneficial outcome of subsequent light therapy.60 In a further study, bright light therapy was significantly beneficial compared to placebo for the treatment of depression.61 It augmented antidepressant effects of medication and wake therapy.61 Furthermore, in patients with dementia, light therapy was demonstrated to have a modest benefit in improving some cognitive and non-cognitive symptoms of dementia in a randomised control trial with melatonin supplement.62 To counteract the adverse effect of melatonin on mood, the study recommended its prescriptive use only in combination with light therapy.

However, in a recent study antidepressant response to bright light treatment in older adults was not statistically superior to placebo. Both treatment and placebo groups experienced a clinically significant overall improvement of 16%.63 There is very limited data which is currently available, suggesting that further research is warranted.

Environment

Smoking and smoking cessation

Whilst it is well recognised that depression is a major risk factor for smoking and there is a strong relationship between mental disorders and smoking,64, 65 according to a prospective study66 of more than 15 000 teenagers, smokers were 4 times more likely to develop depressive symptoms over a 1-year period than teenagers who did not smoke. The strong association remained even after accounting for other risk factors (e.g. low socioeconomic status and low self-esteem). The study reports that smoking itself may be a cause for depression via the activity of nicotine on the central noradrenergic receptor systems. Recently it has been reported that there is a relationship between smoking status and continuously distributed depressed mood among a cohort of adolescents.67 Moreover, the relationship between cigarette smoking and depression may be a factor in the development of subsequent dependence.67 It would appear that advising against heavy or any cigarette intake may be useful for the management of depression.

Substance abuse and drug intake

Substance abuse and drug intake is common in depression. About one-third of patients with major depressive disorders also have substance use disorders, associated with higher risk of suicide and greater social and personal impairment as well as other psychiatric conditions.68

Physical activity

Exercise

There is strong evidence to support the benefits of exercise in the prevention and alleviation of symptoms of depression. Although data from randomised trials are limited, results of studies included in a recent review generally support use of exercise as an alternative or adjunctive treatment for depression.69

Early reports highlight the benefits that regular physical activity provides in reducing the risk of developing depression.70 People who do not participate in physical activity are more likely to develop depression compared with those who regularly exercise.71 Regular aerobic and strength training activities can lead to 50% reduction in symptoms of acute depression and anxiety, especially in women and older people.72 Physical activity is equally as effective as some pharmacological treatment (e.g. sertraline) in the management of mild–moderate depression, especially in the elderly. A 10-month study of 156 adult volunteers with major depressive disorders randomly assigned participants to a course of aerobic exercise, sertraline therapy, or a combination of exercise and sertraline. After 4 months all treatment groups exhibited significant therapeutic improvement and after 10 months, the exercise group had significantly lower relapse rates than participants on sertraline therapy alone.73

A Scottish study randomised 86 patients older than 53 with depression and not responding to at least 6 weeks of antidepressants, to twice-weekly group exercise classes (45 minutes of predominantly weight-bearing exercise) or health education talks for 10 weeks.74 Fifty-five percent of the patients in the exercise group compared with 33% in the education talk group experienced a decline of at least 30% in their depressive symptoms. This study suggests that patients with depression should be actively encouraged to attend group exercise activities and regular physical activity, such as aerobic classes, or an early morning walk of greater than 60 minutes daily. This would at least also take advantage of sunshine exposure or light therapy even on overcast winter days.75

Exercise has been demonstrated to also improve mood in patients with severe affective disorders, according to a small pilot study of 12 participants.76 The study concluded that exercise produced changes in concentration of several biologically active molecules such as adrenocorticotrophic hormone, cortisol, catecholamines, opioid peptides, and cytokines, which have been reported to affect mood or are involved in the physiopathology of affective disorders.77 Moreover, endurance exercise may help to achieve substantial improvement in the mood of selected patients with major depression in the short time.78 Also, there is sufficient evidence to support appropriate physical activity as an intervention to enhance a cancer patient’s physical functioning and psychological wellbeing.79

A recent Cochrane review evaluated 28 trials which fulfilled the inclusion criteria, and of which 25 provided data for the meta-analyses.80 Randomisation was adequately concealed in only a few of the studies, and most did not use intention to treat analyses. Also most of the studies used self reported symptoms as outcome measures. For the 23 trials consisting of 907 participants comparing exercise with no treatment or a control intervention, the pooled SMD was −0.82 (95% CI –1.12, −0.51), indicating a large clinical effect. However when trials with robust designs only were included in the analysis namely, adequate allocation concealment and intention to treat analysis and blinded outcome assessment, the pooled SMD was −0.42.95% CI −0.88, 0.03 that is a moderate, non significant effect was observed.80Hence the study concluded that physical activity gives the impression to improve depressive symptoms in people with a diagnosis of depression, but when only methodologically robust trials are included, the effect sizes are only moderate and not statistically significant. Further robust trials are warranted. Further analysis of the Cochrane review confirmed exercise may improve depression but the majority of trials again had weaknesses.2

Yoga

An early study81 has demonstrated that the daily practice of yoga was able to significantly improve symptoms of depression, and in 1 randomised study was statistically as effective as ECT and imipramine.82 Another study of men and women found yoga significantly improved mood scores for depression and other psychological states such as anxiety, anger and ‘neurotic symptoms’.83

A review of the evidence reveals that yoga has potentially beneficial effects as an intervention on depressive disorders.46 Variation in interventions, severity and reporting of trial methodology suggests that the findings must be interpreted with caution. A number of the interventions may not be feasible in those with reduced or impaired mobility and, even so, further investigation of yoga as a therapeutic intervention is warranted.

Nutritional influences

Nutrition and diets

Chocolate

Dark chocolate may play a role in mood enhancement. One study demonstrated that older men who ate chocolate showed statistically significant improvement in feelings of loneliness, happiness, having plans for the future, less depression, better health, optimism and better psychological wellbeing compared with men who ate candy.84

Lactose and/or dairy

Diet plays an equally important role in the management of depression. As an example, lactose malabsorption may play a role in the development of depression.85 Lactose malabsorption is characterised by a deficiency of mucosal lactase (an enzyme) and, as a consequence, lactose that reaches the colon is broken down by bacteria to short-chain fatty acids, CO2, and H2. Bloating, cramps, osmotic diarrhoea, and other symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are the consequence and can be seen in about 50% of lactose malabsorbers. Thirty women aged 16–60 were all screened for depression using a questionnaire. The group with lactose malabsorption (n = 6 compared with 24 normal lactose absorbers) had significantly higher scores on the depression questionnaire compared with normal lactose absorbers. The study postulated that lactose malabsorption may cause high intestinal lactose levels that might interfere with L-tryptophan metabolism by binding with L-tryptophan and impeding its absorption, and in turn affect serotonin synthesis and availability.85 Although more research is warranted, lactose malabsorption in patients with signs of mental depression, particularly in those with digestive problems, should be considered.

Seafood consumption

Seafood consumption has been reported to be associated with a lower prevalence of bipolar disorder, according to a systematic review.86 A US-based study reviewed population-based epidemiological studies from 17 countries and found greater rates of seafood consumption (n-3 fatty acids) were associated with lower lifetime prevalence for bipolar I, bipolar II, and bipolar spectrum disorders. Greater seafood consumption (deep sea) was also related to lower lifetime prevalence of major depression in 9 countries.86

General diet advice

Consequently, the general advice for depressed patients would include eating regular, balanced healthy meals, high in fruit, vegetables and deep sea fish (at least 2–3 times per week). Poor dietary choices have been reported to be associated with the development of depressive symptoms.87

Alcohol

Whilst depression can lead to excessive alcohol intake, a cohort study of 1055 individuals followed up from birth to 25 years of age found a clear association of heavy alcohol consumption and alcohol abuse increasing the risk of major depression by 65% after controlling for confounding factors. The authors postulated that alcohol may act as a trigger for genetic markers that increase the risk of mental disorders.88

Nutritional supplements

Fish oils and/or omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids

Fish oil supplementation may play a role in the management of depression and bipolar disorder.

Bipolar disorder

In an early preliminary 4-month double-blind, placebo-controlled trial 30 patients with bipolar disorder were randomised to receive either n-3 fatty acids (9.6 g/day) or placebo (olive oil), in addition to their ongoing treatment.89 The n-3 fatty acids were well tolerated and the group of patients that took n-3 fatty acids had significantly longer periods of remission than the placebo group and a reduction in depressive symptoms over the 4 months of treatment.

A small open label study of bipolar outpatients with depressive symptoms also improved significantly within 1 month of treatment with 1.5–2 g/day of Eicosapentaneoic acid (EPA) with no patients developing hypomania or manic symptoms or side-effects with treatment. The authors concluded that the fatty acids may play a role by regulating neurotransmitter metabolism and larger well-controlled trials are necessary.90

Depression

Several trials indicate omega-3 deficiency may contribute to depression and psychiatric diseases, and dietary fish intake and fish oil supplementation may play a useful role in the management of depression.91, 92

In a case control study of pregnant women, women with lower omega-3 PUFA levels especially due to low dietary intake and fetal diversion, were 6 times more likely to experience depression antenatally, compared with women with higher levels.93 The authors conclude there is a role for increased fish intake and fish oil supplementation during the perinatal period.

In 1 study of middle-aged women with moderate-to-severe psychological distress and depression during the menopausal transition (n = 120), participants were randomly assigned to receive 1.05g ethyl-EPA/d plus 0.15g of ethyl-docosahexaenoic acid/d (n = 59) or placebo (n = 61) for 8 weeks.94

Two recently reported trials with the essential fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) have demonstrated efficacy in depression.95, 96 One study compared the administration of EPA to fluoxetine in major depression and reported that the combination was significantly more effective than EPA or fluoxetine administered separately.96

A review of treatments of depression in children and adolescents identified 1 trial of omega-3 PUFA supplementation was beneficial in depressed children compared with placebo.97

A recent meta-analytic review of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant efficacy of n-3 fatty acids has demonstrated efficacy with a cautionary note.95 Although the meta-analysis showed significant antidepressant efficacy of n-3 PUFAs, it is still premature to validate this finding due to publication bias and heterogeneity of studies available. Large scale, well-controlled trials are needed to find out the favourable target subjects, therapeutic dose of EPA, and the composition of n-3 PUFAs in treating depression.98

Recently, Mischoulon reported that the results of n-3 fatty acid supplementation studies, was promising in the treatment of depression.99 In addition, the n-3 fatty acids have been shown to be safe and might be useful in specific populations, such as the elderly, pregnant or lactating women, and people with medical comorbid conditions. Moreover, patients with mild depression or those who are unresponsive to conventional antidepressants might be the best candidates for alternative treatments such as St John’s Wort (SJW) and n-3 fatty acids.99

Tryptophan

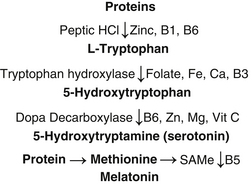

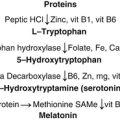

A shift in tryptophan metabolism elicited by pro-inflammatory cytokines has gained attention as a new concept to explain the aetiological and pathophysiological mechanisms of major depression.100 Figure 12.1 illustrates how proteins convert to tryptophan which subsequently converts to serotonin and melatonin requiring various co-factors. Within this research paradigm the use of tryptophan for treating depression has gained popularity.

Tryptophan is an essential amino acid precursor of brain serotonin, making it attractive in the use for depression as well as insomnia. 5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) appears to be the safer form with fewer and milder side-effects and demonstrates equal potency to antidepressants in early clinical trials.101, 102 However there is much debate about the use of 5-HTP for depression despite its widespread use.

Dietary sources of tryptophan may play a role in mental states. Tryptophan is found in most protein based foods and is particularly rich in red meat, oats, milk, yoghurt, cottage cheese, fish, poultry (chicken and turkey), dried dates, chickpeas, sesame, sunflower and pumpkin seeds. A small group of 15 women who had suffered episodes of recurrent major depression but had recovered were studied.103 Participants were randomised to drink either a tryptophan-containing or tryptophan-free mixture. The blood tryptophan levels were 75% less in women drinking the tryptophan-free drink and this was associated with a temporary but clinically significant profile of depressive symptoms. The women who drank the tryptophan-rich drinks had no changes in mental state. The study supports the hypothesis that lowering the brain serotonin activity can precipitate depression. More studies are required to test the potential role of tryptophan for the treatment of depression, especially in relation to any adverse risks.

S-Adenosylmethionine (SAMe)

SAMe is a compound that has been used for many years in Europe as an antidepressant. It became available in the USA as a non-FDA regulated compound in 1999. SAMe resembles a naturally occurring compound in the human body, formed by methionine and adenosine triphosphate (Figure 12.1). SAMe is a co-factor to facilitate the conversion of 5-HT to melatonin and appears to increase central turnover of dopamine and serotonin. It increases the main metabolite of central serotonin-5-HIAA (5–hydroxyindoleacetic acid) in the cerebrospinal fluid.104, 105

A review of the clinical studies with SAMe demonstrated safety and efficacy in the treatment of mild–moderate depression, although further research is required to clarify its role as a first-line treatment for depression.106 Although the exact mechanism is not clear, SAMe is able to maintain high concentrations of serotonin and L-dopamine in the central nervous system (CNS) by inhibiting their degradation. An early meta-analysis of 6 RCTs found that 70% of the participants showed some response to SAMe compared with placebo 30%.107

In recent clinical trials SAMe has demonstrated further efficacy. Thirty antidepressant-treated adult outpatients with resistant major depressive disorder received 800 to 1600mg of SAMe tosylate over a 6-week trial.108 Intention-to-treat analyses based on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale showed a response rate of 50% and a remission rate of 43% following augmentation of SSRIs or venlafaxine with SAMe.

SAMe has also been investigated secondary to the development of chronic diseases such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and HIV/AIDS.109 In PD patients although uncontrolled and preliminary, the study suggested that SAMe was well tolerated and could be a safe and effective alternative to the antidepressant agents used in patients with PD.109 In HIV/AIDS patients, SAMe has a rapid effect evident as soon as week 1 with progressive decreases in depression symptom rating scores throughout the 8 week study.110

Summary

A review conducted by Thachil et al. on the evidence for CM therapies used in depression by studies on CM as monotherapy reported that 19 studies yielded grade I evidence for the use SJW, tryptophan / 5–hydroxytryptophan, SAMe and folate in depressive disorders.111 The review also found grade II evidence for the use of saffron in mild to moderate depression, but large-scale trials are warranted to investigate further its potential as an effective treatment.

Vitamins

Folate and B group vitamins

Recent reviews concluded that the available evidence suggests that folate may have a potential role as a supplement for the treatment of depression.112, 113 This is further supported by a more recent review that concluded that treatment with folate, B12, and B6 can improve cerebral function.114 It is currently unclear if this is the case both for people with normal folate levels, and for those with folate deficiency.

Folate deficiency and low folate status have been linked in a number of clinical studies to depression and poor antidepressant response.115, 116 Research has demonstrated that folate concentrations were lower in depressed patients compared with participants who had never been depressed and suggest that supplementation may be indicated following a depressive episode.116 In a randomised placebo-controlled trial folic acid was observed to be a simple method of greatly improving the antidepressant action of fluoxetine.117 Folic acid should be given in doses sufficient to decrease plasma homocysteine.118 In a recent review reporting on the data from several studies it was tabulated that depressive and cognitive function could be rescued with doses of folate ranging from 0.4–1.0mg.118 Men may require a higher dose of folic acid to achieve this than women, but more work is required to ascertain the optimum dose of folic acid.113 A recent Cochrane review assessed 3 trials of 247 patients and concluded that folate could have a potential role as a supplement to other treatments for depression.113

Vitamin Bs and B6 act as cofactors in the production of CNS serotonin and this may explain its potential role in boosting mental state. Evidence for vitamin B12 supplementation is not as strong, despite a Finnish study of 115 outpatients aged 21–69 years with major depressive disorder demonstrating that higher serum vitamin B12 levels were significantly associated with a better therapeutic outcome for depression.119 A number of studies have also explored low levels of vitamins B1, B2 and B6 and their association with depression and the possible role in supplementation to augment antidepressants in the treatment of geriatric depression.120 However, it should be noted that a recent trial reported that treatment with B12, folic acid, and B6 at doses of 400 microgram B12 + 2mg folic acid + 25mg B6 per day was no better than placebo at reducing the severity of depressive symptoms or the incidence of clinically significant depression over a period of 2 years in older men.121

Vitamin D

A growing body of evidence suggests merit in screening patients with depression for vitamin D deficiency.122, 123 Vitamin D deficiency is common in the elderly and is associated with lower mood and worse cognition.124

A recent study of 53 inpatients from a private psychiatric hospital demonstrated significantly lower levels of vitamin D of less than or equal to 50mmol/L in 60% of patients compared with 30% of the 691 community-based controls. Vitamin D levels of 25mmol/L or less was detected in 11% of inpatients compared with 7.2% of controls respectively. The researchers concluded that patients with depression may benefit with supplementation of oral vitamin D.125 In another recent trial, the results appear to strongly suggest that there is a relationship between reduced serum levels of 25(OH)D and symptoms of depression.126 Moreover, it was concluded that supplementation with high doses of vitamin D ameliorated the symptoms of depression, indicating a possible causal relationship.125

Multivitamins

A 1-year randomised, double-blind study in the UK investigated the effects of multivitamin supplementation on mood and mental health status.127 In the study, 129 healthy adults with a mean age of 20–56 years were randomised to take placebo or vitamin supplements in the form of 2 capsules daily. The vitamin supplement consisted of vitamin A, vitamin E, thiamin, riboflavin, pyridoxine, vitamin B12, vitamin C, folic acid, biotin, nicotinamide at 10 times the recommended daily dose, with the exception of vitamin A. The change of mood was only significant after 1 year. There was reported improvement in sleep, mood parameters and a tendency to feel more agreeable.127

Minerals

Magnesium

Magnesium is an important modulator of N–methyl D–aspartate (NMDA) receptor activity for glutamate.128 Recent research indicates that disturbances of glutamatergic transmission primarily via the NMDA-receptor are involved in pathogenesis of mood disorders. Magnesium deficiency is related to a variety of psychological symptoms, especially depression.129, 130 Early reports have documented that psychiatric symptoms of magnesium deficiency are unspecific, ranging from apathy to psychosis, and may be attributed to other disease processes associated with poor intake, defect absorption or excretion of magnesium.130 In a further study with depressed patients it was reported that there was significant confounding present in this study due to gender differences and clinical subgroup allocation.131 The erythrocyte magnesium level tended to normalise in parallel with clinical improvement, depending on sex and clinical subgroup, and was hypothesised subsequently to be related to the intensity of the depression.131 An additional small study by this research group with 53 male and female drug-free major depressed patients further reported that low plasma magnesium in erythrocytes and plasma was shown to be associated with the intensity of the depression.132

Calcium

The intracellular calcium concentration has important roles in the triggering of neurotransmitter release and the regulation of short-term plasticity.133

A review has reported that clinical trials in women with PMS have found that calcium supplementation effectively alleviates the majority of mood and somatic symptoms.134 Evidence to date indicates that women with luteal phase symptomatology have an underlying calcium dysregulation with a secondary hyperparathyroidism and vitamin D deficiency.134 Hence, indeed supplementation with calcium and vitamin D may be warranted.

Zinc

A recent review has concluded that all the data indicates the important role of zinc homeostasis in psychopathology and therapy of depression, and the potential clinical antidepressant activity that zinc may possess.135 Hence, low blood zinc has been reported to have a role in the development of depression.135 and has been reported to be a sensitive marker of treatment resistance for depression.136 Early studies, have reported that serum and plasma zinc levels were significantly lower in major depressed patients than in normal controls, whereas minor depressed patients showed intermediate values.137, 138 Zinc has been reported to cause toxicity with excess supplementation, hence caution is advised.139

Herbal medicines

St John’s wort (SJW) (Hypericum perforatum)

Studies indicate that SJW extracts improve mood, reduce anxiety and somatic symptoms, and assist with sleep in mild to moderate and major depression. Several active constituents have been isolated from the leaves and to a lesser extent the flowers, including melatonin, hypericin, adhyperforin and hyperforin. SJW is thought to act as a serotonergic (5-HT3 and 5-HT4) receptor antagonist and the active constituents, hyperforin and adhyperforin, may modulate the effect and inhibit reuptake of the neurotransmitters serotonin, dopamine, and noradrenalin. Hyperforin may also inhibit synaptic reuptake of gamma-butyric acid (GABA) and L-glutamate.140, 141

Recent systematic and Cochrane reviews have reported that SJW is the only herbal remedy found to be effective as a treatment for mild to moderate and major depression.142–144

In a meta-analysis, 5 trials were described that involved 2231 patients that compared SJW with conventional antidepressants. Roder et al. found both approaches to be equally effective.144 SJW was significantly effective when compared with placebo in 25 trials involving a total of 2129 patients.

An early meta-analysis of 23 randomised trials with a total of 1757 outpatients suffering mild–moderate depression, demonstrated strong evidence for the efficacy of SJW in the treatment of depression.145 Fifteen trials were tested against a placebo and 8 trials versus antidepressants. The conclusion was that SJW was useful in the treatment of mild–moderate depression, superior to placebo and comparable with conventional drug treatment, with less side-effects and dropouts. A Cochrane review of 37 trials, 26 compared with placebo and 14 compared with an antidepressant concluded that the evidence favoured SJW as being more effective than placebo but results were inconsistent overall for the treatment of mild–moderately severe depression.146

In an RCT of the active extract of SJW ZE 117 (dose of 250mg) it was reported to be comparable with imipramine (75mgs) in the treatment of patients with mild–moderate depression, and better tolerated.147 Similar findings were found with an RCT of SJW ZE 117 and fluoxetine for the treatment of mild–moderate depression.148 Moreover recently it was reported that SJW did not differ significantly from SSRIs with respect to efficacy and adverse events in patients with major depressive disorders.149 This was further supported in a recent extensive Cochrane systematic review where it was concluded that SJW was as effective for treating major depression as standard drugs.142, 146 This study investigated 29 trials (that included 5489 participants) which consisted of 18 comparisons with a placebo intervention and 17 comparisons with synthetic standard antidepressants and which met the inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis. The results of the placebo-controlled trials showed marked heterogeneity. In 9 larger trials that compared active treatment to placebo demonstrated a combined response rate ratio for Hypericum extracts of 1.28 (95% CI, 1.10–1.49) and from 9 smaller trials it was 1.87.95% CI, 1.22–2.87. The results of trials that compared Hypericum extracts to standard antidepressants were statistically homogeneous. Compared with tri- or tetracyclic antidepressants and SSRIs, respectively, the relative risks were 1.02 (95% CI, 0.90–1.15) for 5 trials combined and 1.00 (95% CI, 0.90–1.11) for 12 trials combined. It was also noted that the reported findings were more favourable to Hypericum and that the studies originated from German-speaking countries in both the placebo-controlled trials and in the trials that compared Hypericum to standard antidepressants.142 Participants given Hypericum extracts dropped out of trials due to adverse effects less frequently than those given older antidepressants (odds ration [OR] 0.24 [95% CI, 0.13–0.46] or SSRIs. OR 0.53, 95% CI, 0.34–0.83]). The study suggested that the Hypericum extracts tested included in the trials were superior to placebo in patients with major depression, that they had similar effectiveness to standard antidepressants and had fewer side-effects than standard antidepressants.142

St John’s wort and Sertraline

In a double-blind controlled study of 340 patients with severe major depression (adults with mean age 42 years) 66% women were randomised to receive either SJW 900–1500mg, Sertraline 50–100mgs or placebo for 8 weeks.150 of interest both SJW and Sertraline were equally effective but placebo scored better than both in the treatment of depression. The benefit of placebo was 32% improvement in depression symptom score, compared with SJW 24% and Sertraline treated patients 25%. Side-effects were more frequent in the SJW and Sertraline groups than in the placebo group. A recent similar study investigating a Hypericum perforatum extract WS 5570 at doses of 600mg/day (once daily) and 1200mg/day (600mg twice daily) were found to be safe and more effective than placebo, with comparable efficacy of the WS 5570 groups for the treatment of moderate to major depression.151 Extract WS 5570 (dose of 1800mg/day for 6 weeks) was compared to paroxetine 20–40mg/day in patients with moderate to severe depression. At 2 weeks doses were doubled in 57% of SJW group and 48% in paroxetine group, due to slow response.152 At 6 weeks, 70% and 60% of the SJW and paroxetine group respectively responded to treatment, with a greater mean of improvement in depression scores in the SJW group. Remission occurred in more of the SJW group compared with the paroxetine group. There were fewer adverse events among patients taking Hypericum compared with paroxetine. Hence SJW was at least as effective as paroxetine in moderate to severe depression in people with low suicidal risk.152

SJW drug interactions

Herb–drug interactions are important aspects associated with SJW.153 SJW has been reported to induce the action of the hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes which metabolise a variety of drugs in the liver. By reducing the plasma concentrations of the drugs, SJW has the potential to reduce the effectiveness of at least 50% of all marketed medications.154 These include the therapeutic effects of drugs such as the Oral Contraceptive Pill, potentially increasing the risk of pregnancy, and reducing blood levels of warfarin, digoxin, protease inhibitors, theophylline, phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbitone, indinavir and cyclosporine as they are all metabolised by the CYTP450 pathway. Further, SJW should be avoided in patients taking any antidepressants including monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), having the potential to cause excess CNS serotonin concentrations, resulting in serotonin syndrome characterised by altered mental status, autonomic dysfunction and neuromuscular abnormalities.

Ginkgo biloba

In a randomised, double-blind, 22-week trial 400 patients with dementia associated with neuropsychiatric features were treated with Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 (240mg/day) or placebo. The study demonstrated improvements in favour of EGb 761 for apathy/indifference, anxiety, irritability/lability, depression/dysphoria and sleep/night time behaviour.155

Ginkgo biloba and SSRIs induced sexual dysfunction

In an open trial, Ginkgo biloba was found to be 84% effective in treating antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction predominately caused by SSRIs.156 In the trial, 33 women and 30 men participated for 4 weeks. They were prescribed on average 209mg/day ginkgo biloba extract that was well tolerated. Women reported a higher success rate (91%) than men (76%) on all 4 phases of the sexual response cycle. Other noted benefits included improved cognitive functioning, mental clarity and memory, and enhanced energy level, consistent with Ginkgo biloba’s known cerebral-enhancing effects. Side-effects included GIT disturbances, headache, and general CNS activation. However, a subsequent study did not support these earlier findings.157

Saffron (Crocus sativus L.)

A number of recent preclinical and clinical studies indicate that stigma and petal of Crocus sativus may have an antidepressant effect. In a recent double-blind and randomised trial, patients were randomly assigned to receive a capsule of petal of C. sativus 15mg bid (morning and evening) (Group 1) and fluoxetine 10mg bid (morning and evening) (Group 2) for an 8-week study. At the end of trial, petal of C. sativus was found to be effective similar to fluoxetine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression.158 In addition, in both treatments, the remission rate was 25%. There were no significant differences in the 2 groups in terms of observed side-effects. Earlier studies have demonstrated a similar trend of efficacy for the treatment of mild to moderate depression.159–161

Rhodiola rosea L

A recent clinical trial with a standardised extract of SHR-5 of rhisomes of Rhodiola rosea L. in patients suffering from a current episode of mild to moderate depression demonstrated efficacy.162 An antidepressive effect when administered in dosages of either 340 or 680mg/day over a 6-week period was reported.

Other herbal therapies

There are other herbs that have been commonly employed for the treatment of depression, but as yet have not been clinically trialled, and these include vervain, oat straw, scullcap and lemon balm.163

Aromatherapy

The antidepressant properties of essential oils such as bergamot (Citrus bergamia) and geranium (Pelargonium graveolens) were summarised in a report offering clinical and neuropharmacological perspectives of aromatherapy in managing psychiatric disorders.164 Although some studies demonstrated an association between aromatherapy and improvement in mood in healthy adults, there was a notable lack of methodologically useful trials in clinically depressed populations. A study of 56 healthy men and women found essential oil of lemon improved mood, whilst lavender had no sedating effects compared with control odour of distilled water.165 Hence no conclusions could be drawn regarding the efficacy of aromatherapy in treating depression until controlled trials are conducted.

A recent systematic review of the literature including 18 studies found that ‘credible evidence that odours can affect mood, physiology and behaviour exists’, however, methodological problems led to inconsistencies in the data.166

Hormones

Females and hormones

Accumulating evidence suggests that estrogens may have therapeutic effects in severe mental illnesses, including schizophrenia, via neuromodulatory and neuroprotective activity. Lowered oestrogen, progesterone, DHEA and testosterone hormone levels in women during and after menopause may also contribute to emotional disturbance such as depression and may warrant suitable hormone therapy.168 In a recent RCT it was demonstrated that estradiol appeared to be a useful treatment for women with schizophrenia and could provide a new adjunctive therapeutic option for patients with severe mental illnesses.169, 170

Physical therapies

Acupuncture

A systematic review of RCTs investigating the efficacy of acupuncture in treating depression examined 9 RCTs, 5 of which were considered to be of poor methodological quality, and found that acupuncture tended to be as effective as antidepressants in treating depression.172 This study concluded that, whilst the overall evidence remained inconclusive because of the varied methodology and study designs used, further research investigating the use of acupuncture in treating depression was warranted. A recent trial investigating the clinical therapeutic effect and safety of combined electro-acupuncture and fluoxetine for treatment of mild or moderate depression with physical symptoms was completed and reported a better therapeutic effect on depression and less adverse reactions.173

Massage therapy

A study of 32 depressed adolescent mothers receiving ten 30-minute sessions of massage therapy or relaxation therapy over a 5-week period resulted in both groups reporting lower depression scores but only the massage therapy group demonstrated significant reduction in anxiety, and salivary and urine cortisol levels also.174

Another study of 84 depressed 2nd trimester pregnant women were randomly assigned to massage therapy group (twice weekly 20 minutes), or a progressive muscle relaxation group (twice weekly 20 minutes), or a control group that received standard prenatal care alone. Women reported lower levels of anxiety and depressed mood and less leg and back pain in the massage therapy group, and also higher blood dopamine and serotonin levels and lower levels of cortisol and noradrenalin, contributing to better neonatal outcome (lesser incidence of prematurity and low birth weight).175

Conclusion

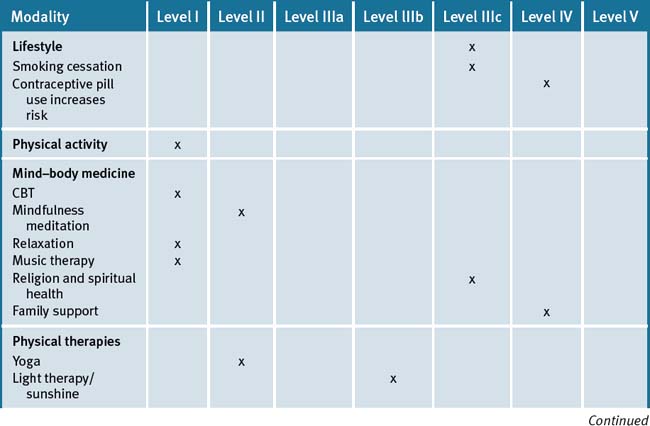

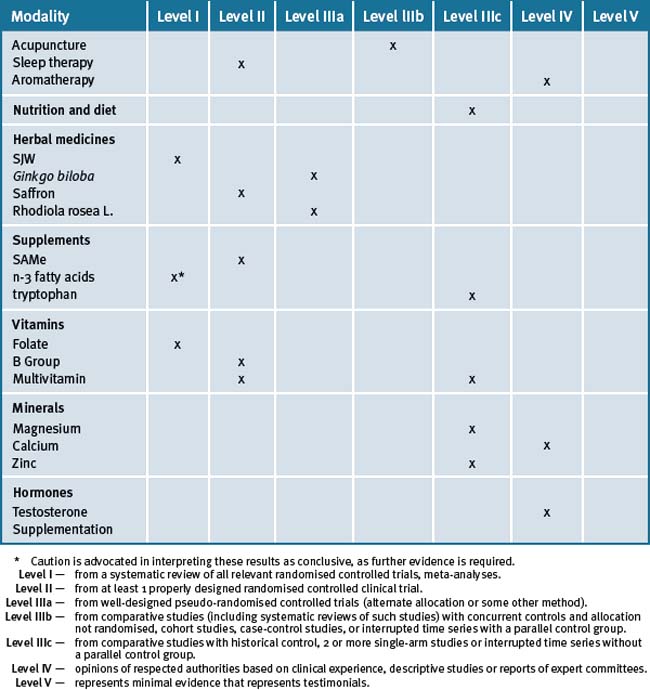

A holistic approach by addressing lifestyle factors and trialling the use of evidence-based CMs would appear to play a role in the management of the patient with depression.7 There is documented good scientific evidence for the non-drug management of depression (see Table 12.2).

Clinical tips handout for patients — depression

1 Lifestyle advice

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind–body medicine

5 Dietary changes

7 Supplements

St John’s wort

Fish oils

Vitamin B’s especially B6 and B12

Vitamin D (cholecalciferol 1000 international units)

Doctors should check blood levels and suggest supplementation if levels are low.

Magnesium and calcium (best provided together)

Zinc

1 World Health Organization (WHO). Online Available: http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/definition/en (accessed July 2008).

2 McAvoy BR. Exercise may improve depression PEARLS No. 139, January 2009.

3 Manual of Mental Disorders. revised, 4th edn, Washington DC: American OPsychiatric Association, 1999.

4 Alboni P., Favaron E., Paparella N., et al. Is there an association between depression and cardiovascular mortality or sudden death? J Cardiovasc Med. 2008;9(4):356-362.

5 Golden S.H. A review of the evidence for a neuroendocrine link between stress, depression and diabetes mellitus. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2007;3(4):252-259.

6 van der Watt G., Laugharne J., Janca A. Complementary and alternative medicine in the treatment of anxiety and depression. Curr Opin Psych. 2008;21(1):37-42.

7 Werneke U., Turner T., Priebe S. Complementary medicines in psychiatry: review of effectiveness and safety. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:109-121.

8 Frazer C.J., Christensen H., Griffiths K.M. Effectiveness of treatments for depression in older people. Medical Journal of Australia. 2005;182(12):627-632.

9 Jorm A.F., Christensen H., Griffiths K.M., et al. Effectiveness of complementary and self-help treatments for depression MJA. 2002 May 20;176(Sppl):S84-S96.

10 Howie J.G., Heaney D.J., Maxwell M., et al. Quality at general practice consultations: cross sectional survey. BMJ. 1999;319(7212):719-720.

11 Kreuter M.W., Chheda S.G., Bull F.C. How does physician advice influence patient behaviour? Evidence for a priming effect. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(5):426-433.

12 Swartz H.A., Frank E., Zuckoff A., et al. Brief interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed mothers whose children are receiving psychiatric treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(9):1155-1162.

13 Driessen E., Van H.L., Schoevers R.A., et al. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy versus Short Psychodynamic Supportive Psychotherapy in the outpatient treatment of depression: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:58.

14 Cuijpers P., van Straten A., Smit F., et al. Preventing the onset of depressive disorders: a meta-analytic review of psychological interventions. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(10):1272-1280.

15 Kendler K.S., Hettema J.M., Butera F., et al. Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onsets of major depression and generalised anxiety. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003 Aug;60(8):789-796.

16 Farmer A.E., McGuffin P. Humiliation, loss and other types of life events and difficulties: a comparison of depressed subjects, healthy controls and their siblings. Psychol Med. 2003 Oct;33(7):1169-1175.

17 van der Wal M.F., de Wit C.A., Hirasing R.A. Psychosocial health among young victims and offenders of direct and indirect bullying. Pediatrics. 2003 Jun;111(6 Pt 1):1312-1317.

18 Klomek A.B., Sourander A., Kumpulainen K., et al. Childhood bullying as a risk for later depression and suicidal ideation among Finnish males. J Affect Disord. 2008 Jul;109(1-2):47-55. Epub 2008 Jan 24

19 Kumpulainen K. Psychiatric conditions associated with bullying. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2008 Apr-Jun;20(2):121-132.

20 Vitetta L., Anton B., Cortiso F., et al. Mind-body medicine: stress and its impact on overall health and longevity. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1057:492-505.

21 Vlastelica M. Emotional stress as a trigger in sudden cardiac death. Psychiatr Danub. 2008;20(3):411-414.

22 DeRubeis R.J., Gelfand L.A., Tang T.Z., et al. Medications versus cognitive behaviour therapy for severely depressed outpatients:mega-analysis of four randomised comparisons. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(7):1007-1013.

23 Wolf N.J., Hopko D.R. Psychosocial and pharmacological interventions for depressed adults in primary care: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(1):131-161.

24 Highet N., Drummond P. A comparative evaluation of community treatments for post-partum depression: implications for treatment and management practices. Aust NZJ Psychiatry. 2004;38(4):212-218.

25 Bottai T. Non-drug treatment for depression. Presse Med. 2008;37(5 Pt 2):877-882.

26 Himelhoch S., Medoff D.R., Oyeniyi G. Efficacy of group psychotherapy to reduce depressive symptoms among HIV-infected individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(10):732-739.

27 Oei T.P., Dingle G. The effectiveness of group cognitive behaviour therapy for unipolar depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2008;107(1-3):5-21.

28 Akechi T., Okuyama T., Onishi J., et al. Psychotherapy for depression among incurable cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2008. CD005537

29 Wilson K.C., Mottram P.G., Vassilas C.A. Psychotherapeutic treatments for older depressed people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2008 Jan 23. CD004853

30 Dobkin R.D., Menza M., Bienfait K.L. CBT for the treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease: a promising nonpharmacological approach. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(1):27-35.

31 Wood A., Trainor G., Rothwell J., et al. Randomised trial of group therapy for repeated deliberate self-harm in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(11):1246-1253.

32 Freedland K.E., Skala J.A., Carney R.M., et al. Treatment of Depression After Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery. A Randomised Controlled Trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;Vol 66(4):387-396.

33 Speca M., Carlson L.E., Goodey E., et al. A randomised, wait-list controlled clinical trial: the effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(5):613-622.

34 Carlson L.E., Speca M., Faris P., et al. One year pre-post intervention follow-up of psychological, immune, endocrine and blood pressure outcomes of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(8):1038-1049.

35 Jorm A.F., Morgan A.J., Hetrick S.E. Relaxation for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2008. Art. No.: CD007142. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007142.pub2

36 McAvoy BR. Relaxation techniques have some benefit in depression PEARLS November 2008;No. 125.

37 Maratos A.S., Gold C., Wang X., et al. Music therapy for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2008. CD004517

38 Koenig H.G., George L.K., Peterson B.L. Religiosity and remission of depression in medically ill older patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(4):536-542.

39 Kendler K.S., Liu X.Q., Gardner C.O., et al. Dimensions of religiosity and their relationship to lifetime psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(3):496-503.

40 Blumenthal J.A., Babyak M.A., Ironson G., et al. For the ENRICHD Investigators. Spirituality, religion, and clinical outcomes in patients recovering from an acute myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(6):501-508.

41 Hassed C.S. Depression: dispirited or spiritually deprived? MJA. 2000;173(10):545-547.

42 McClain C.S., Rosenfeld B., Breitbart W. Effect of spiritual wellbeing on end-of-life despair in terminally-ill cancer patients. Lancet. 2003;361(9369):1603-1607.

43. Vitetta L., Kenner D., Kissane D., et al. Clinical outcomes in terminally ill patients admitted to hospice care: diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. J Palliat Care. 2001;17(2):69-77.

44 Kiecolt-Glaser J., Newton T. Marriage and health: his and hers. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(4):472-503.

45 Hibbard J.H., Pope C.R. The quality of social roles as predictors of morbidity and mortality. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(3):217-225.

46 Pilkington K., Kirkwood G., Rampes H., et al. Yoga for depression: the research evidence. J Affect Disord. 2005;89(1-3):13-24.

47 Riemann D. Insomnia and comorbid psychiatric disorders. Sleep Med. 2007;8(Suppl 4):S15-S20.

48 Morawetz D. Insomnia and Depression: Which Comes First? Sleep Research Online. 2003;5(2):77-81.

49 Hiscock H., Wake M. Infant sleep problems and postnatal depression: a community-based study. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1317-1322.

50 Hiscock H., Wake M. Randomised controlled trial of behavioural infant sleep intervention to improve infant sleep and maternal mood. BMJ. 2002;324(7345):1062-1065.

51 Wojnar M., Ilgen M.A., Wojnar J., et al. Sleep problems and suicidality in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J Psychiatr Res. 2009 Feb;43(5):526-531. Epub 2008 Sep 7

52 Hiscock H., Bayer J.K., Hampton A., et al. Long-term mother and child mental health effects of a population-based infant sleep intervention: cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):e621-e627.

53 Benedetti F., Barbini B., Fulgosi M.C., et al. Combined total sleep deprivation and light therapy in the treatment of drug-resistant bipolar depression: acute response and long-term remission rates. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(12):1535-1540.

54 Brand C.A., Abi H.Y., Cough D.E., et al. Vitamin D deficiency: a study of community beliefs among dark skinned and veiled people. Intern J Rheumatic Dis. 2008;11:15-23.

55 Diamond T.H., Levy S., Smith A., et al. High bone turnover in Muslim women with vitamin D deficiency. MJA. 2002;177:139-141.

56 Lansdowne A.T., Provost S.C. Vitamin D3 enhances mood in healthy subjects during winter. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1998;135(4):319-323.

57 Gloth F.M.III, Allam W., Hollis B. Vitamin D vs broad spectrum phototherapy in treatment of seasonal affective disorder. J Nutr Health Ageing. 1999;3(1):5-7.

58 Kemper K.J., Shannon S. Complementary and alternative medicine therapies to promote healthy moods. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(6):901-926.

59 Jorm A.F., Allen N.B., O’Donnell C.P., et al. Effectiveness of complementary and self-help treatments for depression in children and adolescents. MJA. 2006;185:368-372.

60 Fritzsche M., Heller R., Hill H., et al. Sleep deprivation as a predictor of response to light therapy in major depression. J Affect Disord. 2001;62(3):207-215.

61 Loving R.T., Kripke D.F., Shuchter S.R. Bright light augments antidepressant effects of medication and wake therapy. Depress Anxiety. 2002;16(1):1-3.

62 Riemersma-van der Lek R.F., Swaab D.F., et al. Effect of bright light and melatonin on cognitive and noncognitive function in elderly residents of group care facilities: a randomised controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(22):2642-2655.

63 Loving R.T., Kripke D.F., Elliott J.A., et al. Bright light treatment of depression for older adults. ISRCTN55452501 BMC Psychiatry. 2005;5:41.

64 Jorm A.F., Rodgers B., Jacomb P.A., et al. Smoking and mental health: results from a community survey. MJA. 1999;170:74-77.

65 Jorm A.F. Association between smoking and mental disorders: results from an Australian National Prevalence Survey. AN Z J Publ Health. 1999;23(3):245-248.

66 Goodman E., Capitman J. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among teens. Pediatrics. 2000;106(4):748-755.

67 Munafò M.R., Hitsman B., Rende R., et al. Effects of progression to cigarette smoking on depressed mood in adolescents: evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Addiction. 2008;103(1):162-171.

68 Davis L., Uezato A., Newell J.M., Frazier E. Major depression and comorbid substance use disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008 Jan;21(1):14-18.

69 Barbour K.A., Edenfield T.M., Blumenthal J.A. Exercise as a treatment for depression and other psychiatric disorders: a review. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2007;27(6):359-367.

70 Weyerer S., Kupfer B. Physical exercise and psychological health. Sports Med. 1994;17(2):108-116.

71 Weyerer S. Physical inactivity and depression in the community. Evidence from the Upper Bavarian Field Study. Int J Sports Med. 1992;13(6):492-496.

72 Dunn A.L., Trivedi M.H., O’Neal H.A. Physical activity dose-response effects on outcomes of depression and anxiety. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(6 Suppl):S587-S597.

73 Babyak M., Blumenthal J.A., Herman S., et al. Exercise treatment for major depression: maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10 months. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(5):633-638.

74 Mather A.S., Rodriguez C., Guthrie M.F., et al. Effects of exercise on depressive symptoms in older adults with poorly responsive depressive disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:411-415.

75 Wirz-Justice A., Graw P., Kräuchi K., et al. ‘Natural’ light treatment of seasonal affective disorder. J Affect Dis. 1996;37(2-3):109-120.

76 Dimeo F., Bauer M., Varahram I., et al. Benefits from aerobic exercise in patients with major depression: a pilot study. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35(2):114-117.

77 Hyde J.S., Mezulis A.H., Abramson L.Y. The ABCs of depression: integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychol Rev. 2008;115(2):291-313.

78 Knubben K., Reischies F.M., Adli M., et al. A randomised, controlled study on the effects of a short-term endurance training program in patients with major depression. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(1):29-33.

79 Knobf M.T., Musanti R., Dorward J. Exercise and quality of life outcomes in patients with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2007;23(4):285-296.

80 Mead G.E., Morley W., Campbell P., et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2008. Art. No.: CD004366. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub3

81 Naga Venkatesha Murthy P.J., Janakiramaiah N., et al. P300 amplitude and antidepressant response to Sudarshan Kriya Yoga (SKY). J Affect Disord. 1998;50(1):45-48.

82 Janakiramaiah N., Gangadhar B.N., Naga Venkatesha Murthy P.J., et al. Antidepressant efficacy of Sudarshan Kriya Yoga (SKY) in melancholia: a randomised comparison with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and imipramine. J Affect Disord. 2000;57(1-3):255-259.

83 Shapiro D., Cook I.A., Davydov D.M., et al. Yoga as a Complementary Treatment of Depression: Effects of Traits and Moods on Treatment Outcome. Advance Access Publication 28 February 2007 eCAM. 2007;4(4):493-502. doi:10.1093/ecam/nel1142007

84 Strandberg T.E., Strandberg A.Y., Pitkälä K., et al. Chocolate, wellbeing and health among elderly men. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008 Feb;62(2):247-253. Epub 2007 Feb 28

85 Ledochowski M., Sperner-Unterweger B., Fuchs D. Lactose malabsorption is associated with early signs of mental depression in females: a preliminary report. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(11):2513-2517.

86 Noaghiul S., Hibbeln J.R. Cross-national comparisons of seafood consumption and rates of bipolar disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2222-2227.

87 Avila-Funes J.A., Garant M.P., Aguilar-Navarro S. Relationship between determining factors for depressive symptoms and for dietary habits in older adults in. Mexico Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2006;19(5):321-330.

88 Fergusson D.M., Boden J.M., Horwood L.J. Tests of causal links between alcohol abuse or dependence and major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 Mar;66(3):260-266.

89 Stoll A.L., Severus W.E., Freeman M.P., et al. Omega-3 fatty acids in bipolar disorder: a preliminary double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(5):407-412.

90 Osher Y., et al. Omega-3 eicosapentaneoic acid in bipolar depression: Report of a small open-label study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;66(6):726-729.

91 Mazza M., Pomponi M., Janiri L., et al. Review article. Omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants in neurological and psychiatric diseases: An overview. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2007 January 30;31(1):12-26.

92 Frasure-Smith N., Lespérance F., Julien P. Major depression is associated with lower omega-3 fatty acid levels in patients with recent acute coronary syndromes. Biological Psychiatry. 2004 May 1;55(9):891-896.

93 Rees A., Austin M., Owen C., Parker G. Omega-3 deficiency associated with perinatal depression: Case control study. Psychiatry Research. 2009 April 30;166(2-3):254-259.

94 Lucas M., Asselin G., Mérette C., et al. Ethyl-eicosapentaenoic acid for the treatment of psychological distress and depressive symptoms in middle-aged women: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Feb;89(2):641-651. Epub 2008 Dec 30

95 Jazayeri S., Tehrani-Doost M., Keshavarz S.A., et al. Comparison of therapeutic effects of omega-3 fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid and fluoxetine, separately and in combination, in major depressive disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42(3):192-198.

96 Keshavarz S., Jazayeri S., Tehrani-Doost M., et al. Effects of n-3 fatty acid EPA in the treatment of depression. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67(OCE):E210.

97 Clayton E.H., Hanstock T.L., Garg M.L., et al. Long chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the treatment of psychiatric illnesses in children and adolescents. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2007;19(2):92-103.

98 Lin P.Y., Su K.P. A meta-analytic review of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant efficacy of omega-3 fatty acids. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(7):1056-1061.

99 Mischoulon D. Update and critique of natural remedies as antidepressant treatments. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30:51-68.

100 Miura H., Ozaki N., Sawada M., et al. A link between stress and depression: shifts in the balance between the kynurenine and serotonin pathways of tryptophan metabolism and the etiology and pathophysiology of depression. Stress. 2008;11(3):198-209.

101 Cournoyer G., de Montigny C., Ouellette J., et al. A comparative double-blind controlled study of trimipramine and amitriptyline in major depression: lack of correlation with 5-hydroxytryptamine reuptake blockade. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1987;7(6):385-393.

102 Kahn R.S., Westenberg H.G., Verhoeven W.M., et al. Effect of a serotonin precursor and uptake inhibitor in anxiety disorders; a double-blind comparison of 5-hydroxytryptophan, clomipramine and placebo. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1987;2(1):33-45.

103 Smith K.A., Fairburn C.G., Cowen P.J. Relapse of depression after rapid depletion of tryptophan. Lancet. 1997;349(9056):915-919.

104 Gatto G., Caleri D., Michelacci S., Sicuteri F. Analgesising effect of a methyl donor (S-adenosylmethionine) in migraine: an open clinical trial. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1986;6:15-17.

105 Baldessarini R.J. Neuropharmacology of S-aenosyl-L-methionine. Am J Med. 1987;83(suppl 5A):95-103.

106 Nguyen M., Gregan A. S-adenosylmethionine and depression. Aust Fam Physician. 2002;31(4):339-343.

107 Bressa G.M. S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAMe) as antidepressant: meta-analysis of clinical studies. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1994;154:7-14.

108 Alpert J.E., Papakostas G., Mischoulon D., et al. S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) as an adjunct for resistant major depressive disorder: an open trial following partial or nonresponse to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or venlafaxine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(6):661-664.

109 Di Rocco A., Rogers J.D., Brown R., et al. S-Adenosyl-Methionine improves depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease in an open-label clinical trial. Mov Disord. 2000;15(6):1225-1229.

110 Shippy R.A., Mendez D., Jones K., et al. S-adenosylmethionine (SAM-e) for the treatment of depression in people living with HIV/AIDS. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:38.

111 Thachil A.F., Mohan R., Bhugra D. The evidence base of complementary and alternative therapies in depression. J Affect Dis. 2007;97:23-35.

112 Taylor M.J., Carney S.M., Goodwin G.M., et al. Folate for depressive disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Psychopharmacol. 2004;18(2):251-256.

113 Taylor M.J., Carney S., Geddes J., et al. Folate for depressive disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2003. CD003390

114 Herrmann W., Lorenzl S., Obeid R. Review of the role of hyperhomocysteinemia and B-vitamin deficiency in neurological and psychiatric disorders–current evidence and preliminary recommendations Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2007;75(9):515-527.

115 Bottiglieri T., Laundy M., Crellin R., et al. Homocysteine, folate, methylation, and monoamine metabolism in depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 2000;69(2):228-232.

116 Morris M.S., Fava M., Jacques P.F., et al. Depression and folate status in the US Population. Psychother Psychosom. 2003;72(2):80-87.

117 Coppen A., Bailey J. Enhancement of the antidepressant action of fluoxetine by folic acid: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2000;60(2):121-130.

118 Obeid R., McCaddon A., Herrmann W. The role of hyperhomocysteinemia and B-vitamin deficiency in neurological and psychiatric diseases. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45(12):1590-1606.

119 Hintikka J., Tolmunen T., Tanskanen A., et al. High vitamin B12 level and good treatment outcome may be associated in major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2003;3:17-22.

120 Bell I.R., Edman J.S., Morrow F.D., et al. Brief communication. Vitamin B1, B2, and B6 augmentation of tricyclic antidepressant treatment in geriatric depression with cognitive dysfunction. J Am Coll Nutr. 1992;11(2):159-163.

121 Ford A.H., Flicker L., Thomas J., et al. Vitamins B12, B6, and folic acid for onset of depressive symptoms in older men:results from a 2-year placebo-controlled randomised trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(8):1203-1209.

122 Murphy P.K., Wagner C.L. Vitamin D and mood disorders among women: an integrative review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008;53(5):440-446.