Depressed Consciousness and Coma

Perspective

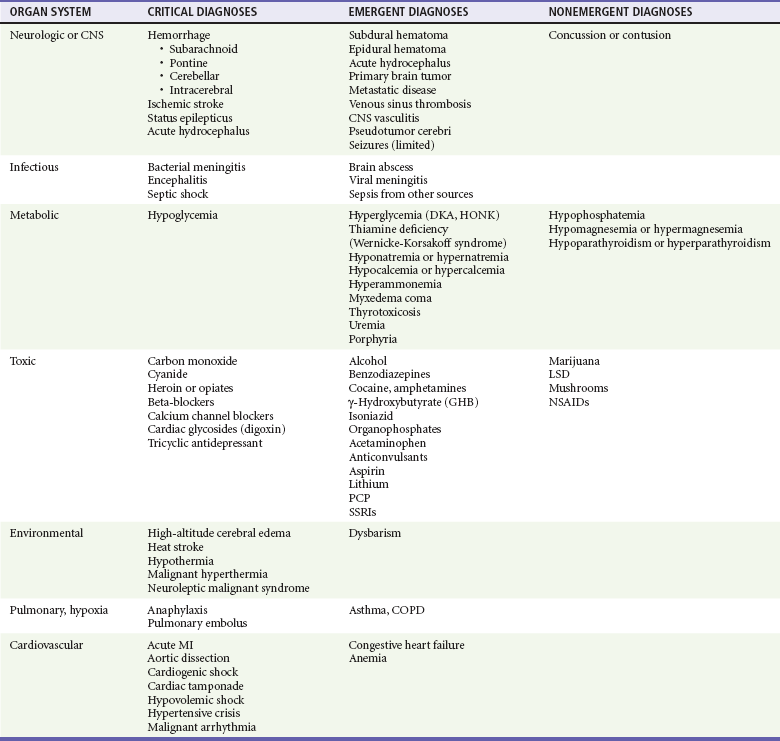

Depressed mental status represents an alteration in arousal and is a common presenting complaint in the emergency department (ED). This presentation can be the manifestation of a wide spectrum of diseases, with the degree of impairment ranging along a continuum from sleepiness to decreased alertness to frank coma. The differential diagnosis of stupor and coma is broad and diverse (Table 16-1) but can usually be categorized into metabolic and systemic, structural, or psychogenic causes. The majority of cases are caused by metabolic or systemic derangements, whereas the remainder are usually caused by structural lesions. Psychogenic presentations are much less common. The differential diagnosis for depressed level of consciousness often overlaps with that for confusion (see Chapter 17). Frequently, diagnosis and management occur simultaneously, and a structured systematic approach is used. A thorough grasp of the underlying pathophysiology leading to the acute depressed mental state will lead to timely diagnosis and treatment.

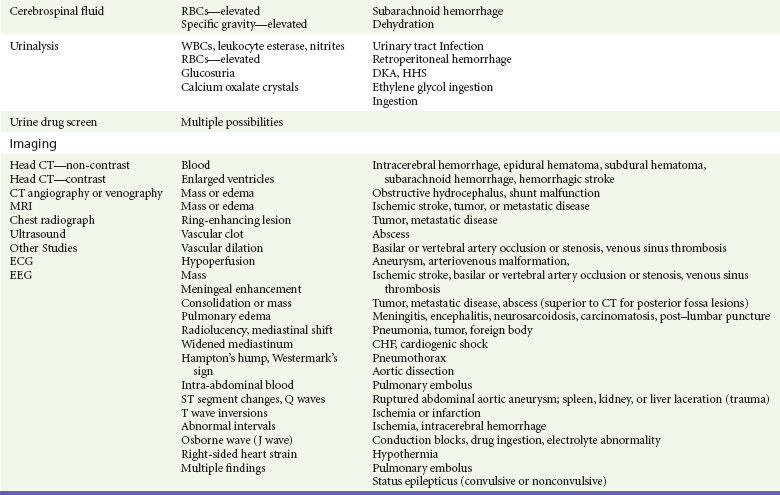

Table 16-1

Pathophysiology

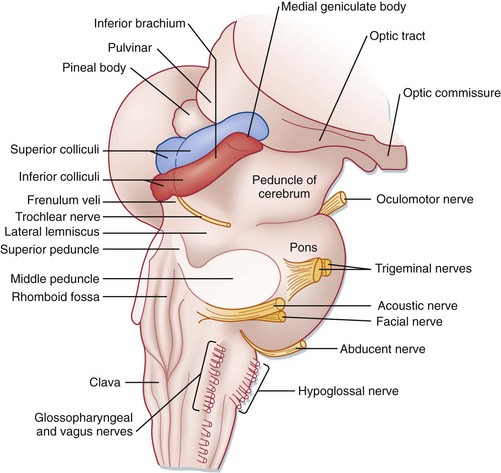

The ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) is the neuroanatomic structure primarily responsible for arousal and cortical activation. It is located in the paramedian tegmental zone in the dorsal part of the brainstem (Fig. 16-1). The input of somatic and sensory stimuli to the cerebral cortex is controlled by the ARAS and functions to initiate arousal from sleep. The brain’s cognition centers are located primarily in the cerebral cortex and serve to determine the content of consciousness.

Diagnostic Approach

Head trauma, stroke, tumor, and infection are the most common structural causes of coma and depressed consciousness. Traumatic causes can include subdural and epidural hematomas, intraparenchymal or subarachnoid hemorrhage, or simply contusion or concussion. Strokes occur with embolic, thrombotic, or hemorrhagic mechanisms, but it is extremely unusual for ischemic (i.e., nonhemorrhagic) stroke to depress consciousness unless a massive insult to both hemispheres has occurred (e.g., diffuse severe cerebral edema after a massive infarct) or a high-grade basilar artery stenosis or occlusion is present.1 Depression of consciousness with CNS infections may be caused by mass effect and is common with severe bacterial meningitis, cerebral abscess or empyema, or parasitic mass. Malignancies, whether primary or metastatic, can cause depressed consciousness if the tumor mass elevates intracranial pressure (ICP) or reduces cerebral blood flow, or if surrounding edema develops rapidly.

Special consideration should be given to specific populations of patients. The elderly, in particular, are susceptible to alterations in therapeutic medication dosage and drug-drug interactions. Even seemingly minor infections, such as urinary tract infections, upper respiratory infections, or viral gastroenteritis, may cause altered mental status (see Chapter 13), depressed consciousness, or coma. In addition, immunocompromised patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or those undergoing chemotherapy treatments for transplants, and patients with malignancy or immunologic disease are vulnerable to a multitude of opportunistic infections not commonly seen in the general patient population.

The clinical evaluation and stabilization of patients with depressed consciousness occur simultaneously with the diagnosis in the ED. The differential diagnosis of depression of consciousness is extensive but can be greatly simplified by focusing attention on the distinguishing characteristics of the available patient history and physical examination (Box 16-1).2 Approaching the patient’s presentation systematically, beginning with a broad differential diagnosis, usually allows development of a short list of likely diagnoses early in the encounter.

Pivotal Findings

Often, information from alternate sources guides the diagnostic workup. Common sources of information include family members, neighbors, prehospital personnel, law enforcement, and nursing home staff.3 They may know of preceding symptoms such as headache, nausea, vomiting, or fever. Key historical information includes the rate of symptom onset, a history of trauma, exposure to drugs or toxins, or new medications or change in dosage. Rate of symptom onset is important, as an abrupt onset of decreased alertness may suggest structural phenomena or vascular insult, whereas a gradual onset would be more indicative of the slow, indolent course frequently seen with toxic, metabolic, or infectious causes. Family members usually have some knowledge regarding the patient’s past medical history, which may include diabetes, liver or renal disease, vascular disease such as hypertension, coronary disease, stroke or transient ischemic attacks, malignancy, seizures, immunocompromised states such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, sickle cell disease, organ transplantation, or psychiatric illness. Family members may also be able to relay additional diagnostic clues such as rate of onset or waxing-waning characteristics of the patient’s symptoms.

In addition, previous medical records should be reviewed whenever possible to augment or confirm the information provided. Items with the patient such as a card in the wallet containing lists of medical conditions and/or medications or a medical alert bracelet or necklace can provide valuable information. If the patient’s historical baseline mental status cannot be established, the current presentation is assumed to be an acute change.4

Causes of depression of consciousness vary with patient age (Box 16-2). The elderly are particularly vulnerable to infectious causes, medication changes, and alterations in their living environments. Young adults and adolescents are more likely to be affected after recreational drug use or trauma. Accidental toxic ingestions are often seen in younger children. In infants, infectious causes of depressed consciousness are most common; however, trauma secondary to physical abuse and metabolic derangements from inborn errors of metabolism can be seen.5

Physical Examination

Immediately after an assessment of the patient’s vital signs, a head-to-toe physical examination is performed.6 A methodical and complete head and neck examination is conducted, with particular emphasis on examination of the pupillary reflexes and eye movements (see later discussion) and any indications of head trauma, including hemotympanum, periorbital ecchymosis, Battle’s sign, scalp hematoma, or CSF otorrhea or rhinorrhea. The hydration of the mucous membranes may give clues to specific toxidromes. Laceration or bruising of the tongue may indicate a recent seizure.

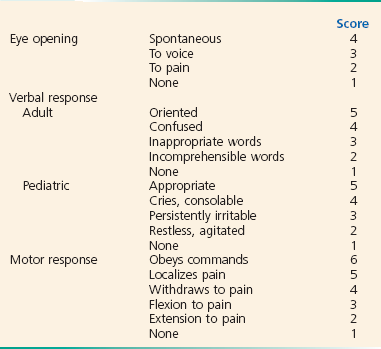

A systematic neurologic examination, with particular attention paid to the eyes, is the most useful tool in differentiating a structural from a systemic or metabolic cause of depressed consciousness or coma. A head-to-toe approach is a proven strategy. This should include evaluation of the patient’s Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score (Box 16-3), level of alertness, cranial nerves, strength, reflexes, and cerebellar functions with emphasis on gait, pronator drift, finger-to-nose, heel-to-shin, rapid alternating movements, and Romberg testing. The GCS measures the best motor and verbal responses and the degree of stimulus required to elicit eye opening and is measured serially, as level of consciousness frequently is dynamic after the initial insult and subsequent response to therapy. The GCS does not differentiate among causes of altered mental status or coma or assess cognition but is useful in monitoring changes in mental status when serial examinations are performed and serves as an objective reference for communicating with consultants.7 A change of two or more points in serial GCS testing represents a significant change.

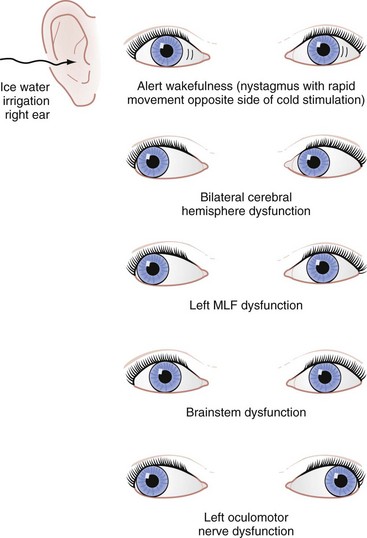

If there are no contraindications, such as suspected cervical spine injury, oculocephalic testing is accomplished by observing the patient’s eye movements while the head is turned from side to side. Patients who exhibit a maintained forward gaze despite head turning (doll’s eye reflex) are unlikely to have a brainstem-mediated cause of coma. If the eyes remain in a fixed position within the orbits, turning in unison with the head, brainstem dysfunction is suggested. Oculovestibular or “cold water caloric” testing is a more sensitive test for brainstem involvement and cannot voluntarily be resisted (Fig. 16-2). After elevation of the patient’s head to 30 degrees (this can be done in patients whose cervical spine is not cleared by placing the bed in the reverse Trendelenburg position), 10 to 30 mL of ice water is used to irrigate the external auditory canal. Tympanic membrane perforation and cerumen impaction should be ruled out before this test is performed. In patients who have an intact brainstem, the response is a slow conjugate deviation of gaze toward the side of the cold water stimulus for 30 to 120 seconds. The reflex is short-lived and followed by corrective fast beats of nystagmus toward the midline. This corrective nystagmus is described by the mnemonic COWS, which stands for “cold-opposite, warm-same.” If there is no response to the irrigation, brainstem dysfunction is possible.

Recently, literature on the phenomenon of basilar artery stenosis or occlusion manifesting as depressed consciousness or coma has increasingly been published. A review of the Lausanne Stroke Registry showed that 100% of patients with poor outcome from high-grade basilar stenosis or occlusion had either stupor or coma or the triad of pupillary abnormalities, dysarthria, and bulbar findings on presentation.1

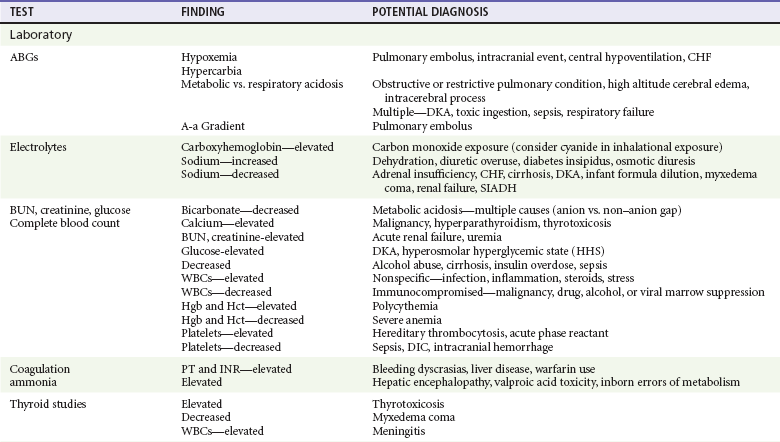

Ancillary Testing (Refer to Table 16-2)

Serum ammonia levels are controversial and have not been shown to be a reliable marker for the cause of depressed consciousness. Although usually associated with severe liver disease, ammonia levels can be elevated in other conditions such as valproic acid toxicity and inborn errors of metabolism and can be normal in patients with hepatic encephalopathy.8 Thyroid function studies can help confirm myxedema coma or thyrotoxicosis. When CNS pathology such as infection or hemorrhage is suggested but not seen on neuroimaging studies, cerebrospinal fluid analysis is undertaken.

Imaging Studies

Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the brain is the initial imaging modality of choice in the setting of depressed consciousness and coma. In the majority of ED settings, it is available and quickly obtained, and this makes CT more suitable than other imaging tests for the patient with borderline hemodynamic instability. Brain CT is sufficiently sensitive to detect most intracranial hemorrhages that are large enough to cause coma. In addition, the presence of hydrocephalus can quickly be assessed. Despite its utility, linear artifacts created by the thick skull base can limit the view of the posterior fossa on CT. In this case, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is generally much better for identifying structural lesions in this region. However, this modality is less practical in most ED settings because of its cost, limited availability, and duration of acquiring each study, which consequently limits the ability to monitor or access the unstable patient.4

Diagnostic Algorithm

Critical diagnoses to consider are listed in Table 16-1.

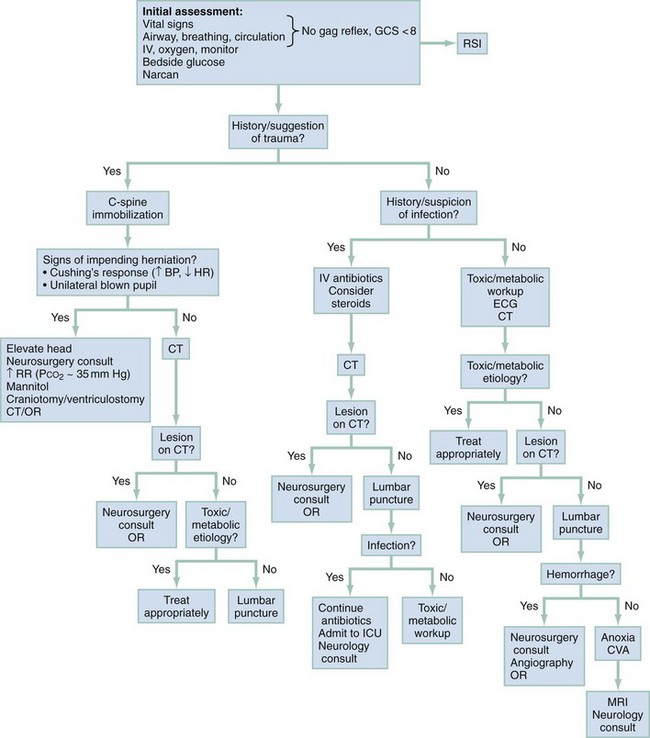

Similarly, owing to the severe morbidity and mortality associated with many causes of depressed consciousness and the ability for rapid reversal of several conditions, initial stabilization, treatment, and assessment are performed simultaneously. A logical approach to the history, physical examination, and diagnostic testing is presented in Figure 16-3.

Empirical Management

Initial establishment of airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs) is of primary importance in stabilizing the patient with altered mental status. Initiation of intravenous access combined with the administration of oxygen and continuous telemetry monitoring should happen concomitantly within the first few minutes of the patient’s arrival.2 In patients with a GCS score lower than 8, intubation is indicated unless the coma is readily reversible, such as that caused by hypoglycemia or opioid overdose (see Chapter 1). All patients should receive a thorough neurologic examination before sedation and chemical paralysis for intubation. Trauma patients require spinal immobilization in addition to indicated fluid resuscitation.

Reversible causes of the patient’s condition should be sought concomitantly with initial stabilization. Administration of the components of the “coma cocktail,” which include dextrose, naloxone, and thiamine, can quickly reverse the alterations in mental status caused by hypoglycemia, narcotic overdose, and thiamine deficiency, respectively, and can substantially narrow the differential diagnosis. Bedside capillary blood glucose, blood, and urine studies should be sent while ECG and emergent noncontrast head CT are ordered. Further therapy and workup will be dictated by the patient’s history and physical examination. Specific attention should be given to identifying the focal neurologic abnormalities, including pupillary reflexes and pathologic eye movements that suggest mass effect or depressed brainstem function, prompting neuroimaging and evaluation by a neurosurgeon. Empirical administration of mannitol and elevation of the head of the bed are indicated when there is clear evidence of transtentorial herniation (see Chapters 41 and 101). In patients with compromised brainstem function who lack evidence of herniation, investigation of possible exposure to toxins or metabolic imbalances should proceed with consideration of basilar artery or bilateral vertebral artery occlusion requiring CT or magnetic resonance angiography. Basilar stenosis or occlusion is one of the few stroke syndromes that can manifest as stupor or coma, and administration of antiplatelet, anticoagulation and thrombolytic agents should be considered in consultation with a neurologist or stroke team.

In patients who demonstrate normal brainstem function, the workup proceeds as supportive care is provided. When an infectious cause is suggested, empirical administration of a broad-spectrum antibiotic should not be delayed for lumbar puncture or other diagnostic tools.9 Lesions or masses found on brain imaging should prompt evaluation by a neurosurgeon and, if indicated, early operative intervention. In patients in whom a toxic ingestion is possible, activated charcoal is of little benefit in most cases. Specific toxin antidotes, if indicated, can be given, with consultation with a local or regional poison center when required. Early hemodialysis after consultation with a nephrologist should also be considered in patients who have toxic or metabolic abnormalities amenable to this therapy.

References

1. Devuyst, G, et al. Stroke or transient ischemic attacks with basilar artery stenosis or occlusion: Clinical patterns and outcome. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:567–573.

2. Hoffman, RS, Goldfrank, LR. The poisoned patient with altered consciousness. Controversies in the use of a “coma cocktail.”. JAMA. 1995;274:562–569.

3. Kanich, W, et al. Altered mental status: Evaluation and etiology in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:613–617.

4. American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy for the initial approach to patients presenting with altered mental status. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:251–281.

5. Kirkham, FJ. Non-traumatic coma in children. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85:303–312.

6. Bateman, DE. Neurological assessment of coma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71(Suppl 1):i13–i17.

7. Koita, J, Riggio, S, Jagoda, A. The mental status examination in emergency practice. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:439–451.

8. Elgouhari, HM, O’Shea, R. What is the utility of measuring the serum ammonia level in patients with altered mental status? Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76:252–254.

9. Brouwer, MC, et al. Nationwide implementation of adjunctive dexamethasone therapy for pneumococcal meningitis. Neurology. 2010;75:1533–1539.