Dentofacial Disharmonies in Adults

Reconstruction and Rejuvenation

• Special Medical Considerations

• Functional Assessment of Head and Neck Structures

• Temporomandibular Disorders: Effects of Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

• Special Wound Healing Risk Factors

• Comprehensive Dental Rehabilitation

• Unique Orthodontic Treatment Considerations

• Previous Suboptimal Facial Surgery

• Facial Aging and Rejuvenation

The techniques for the correction of a dentofacial deformity are basically the same for the middle-aged adult as they are for the teenager and the young adult. To achieve a favorable result in the adult orthognathic patient, it is essential to recognize age-related treatment pitfalls such as medical risk factors; progressive upper airway dysfunction; dental rehabilitation needs, including periodontal and restorative aspects; the effects of facial soft-tissue aging; and the often prolonged physiologic and psychosocial responses to surgery (Figs. 25-1 through 25-11).

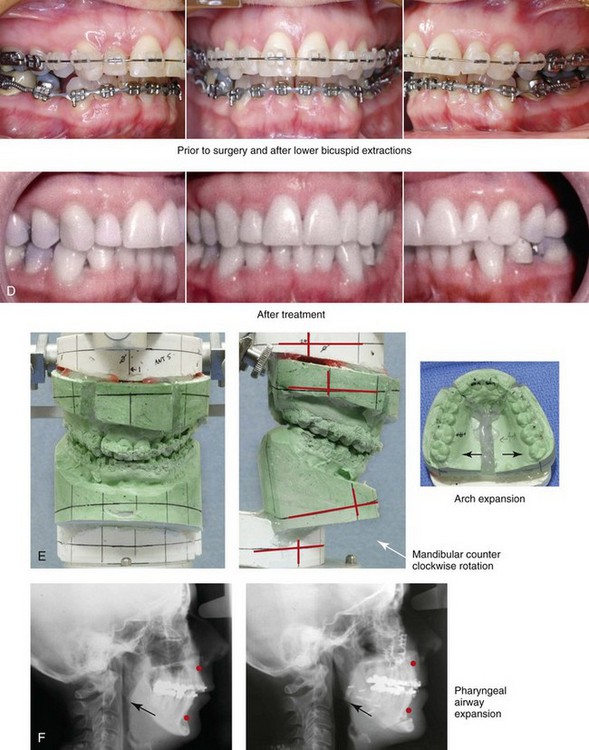

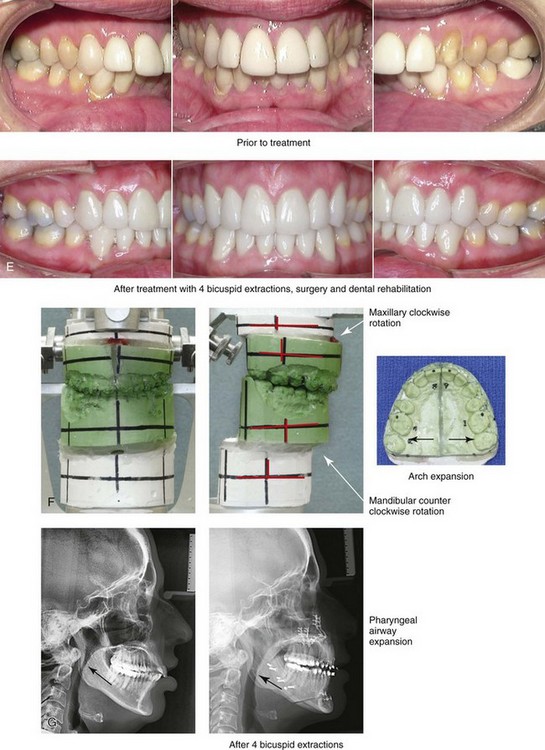

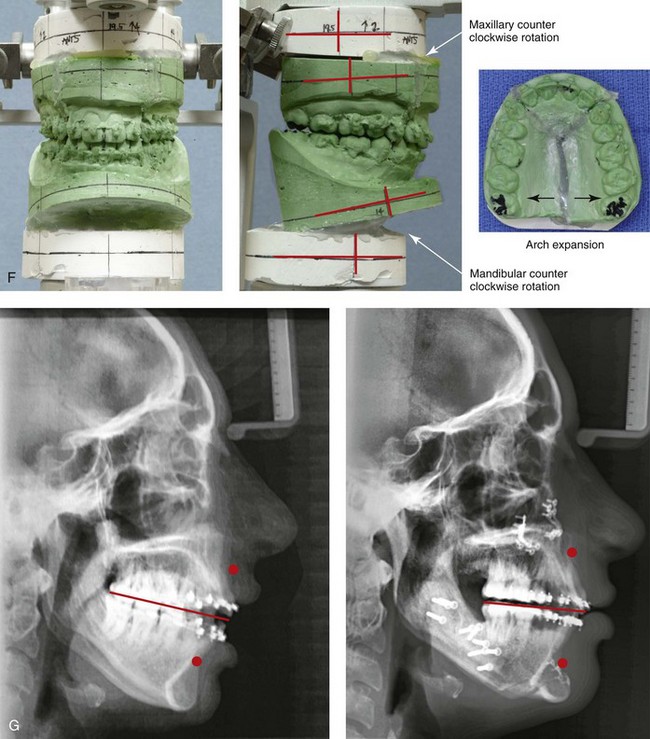

Figure 25-1 A woman in her mid 50s was referred by her general dentist to an orthodontist for the management of a longstanding Class II excess overjet malocclusion that had gradually resulted in the deterioration of the posterior dentition. The orthodontist recognized that the malocclusion resulted from a retrusive mandible and a constricted maxilla. With referral for surgical evaluation, a head and neck examination was completed. In addition to a developmental jaw deformity that involved both the maxilla and mandible, chronic obstructive nasal breathing and a sleep history consistent with obstructive sleep apnea was clarified. Suboptimal facial aging with a desire for an improved neck–chin angle was also discussed. An attended polysomnogram confirmed moderate obstructive sleep apnea. The patient agreed to proceed with orthodontics, including lower first bicuspid extractions to relieve dental compensation in combination with jaw and intranasal surgery. The objectives were to improve the airway, to enhance facial aesthetics, and to achieve improved long-term dental health. The patient’s surgical procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, counterclockwise rotation, arch expansion, and the correction of the curve of Spee); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); an anterior approach to the soft tissues of the neck (cervical flap elevation, neck defatting, and vertical platysma muscle plication); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Facial views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction. Note the improved A-point to B-point relationship. D, Occlusal views with orthodontics in progress (lower bicuspid extractions) and after treatment. E, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. F, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after surgery. Note the improved posterior airway space documented.

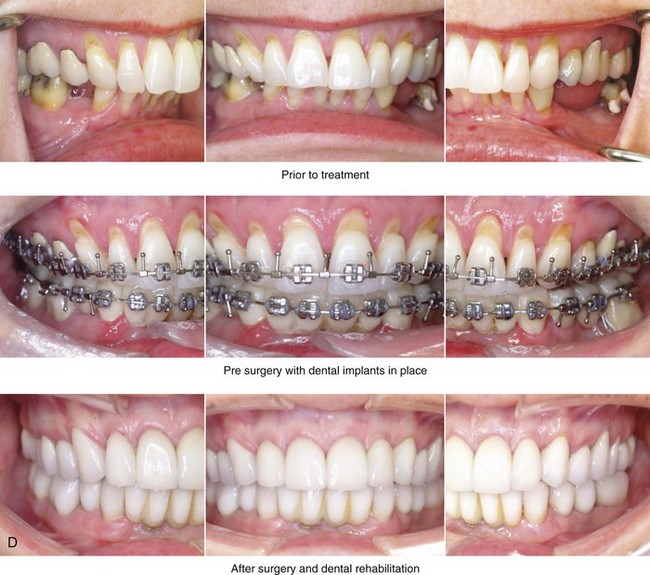

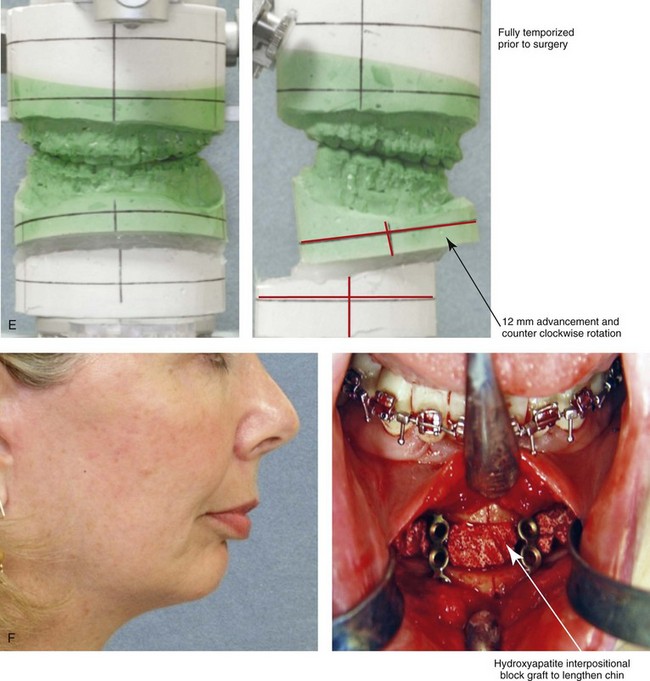

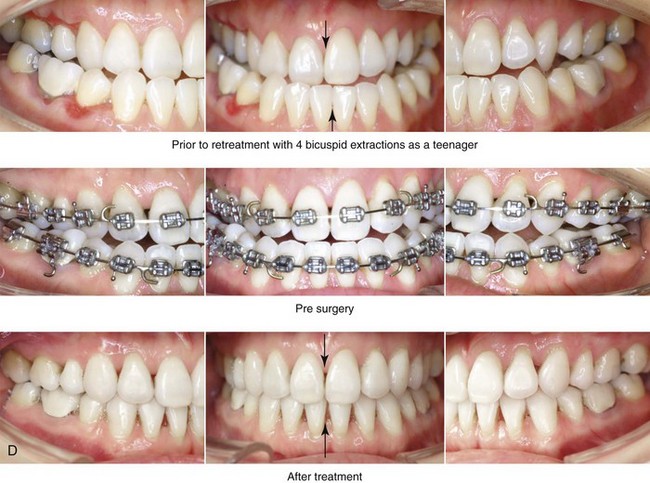

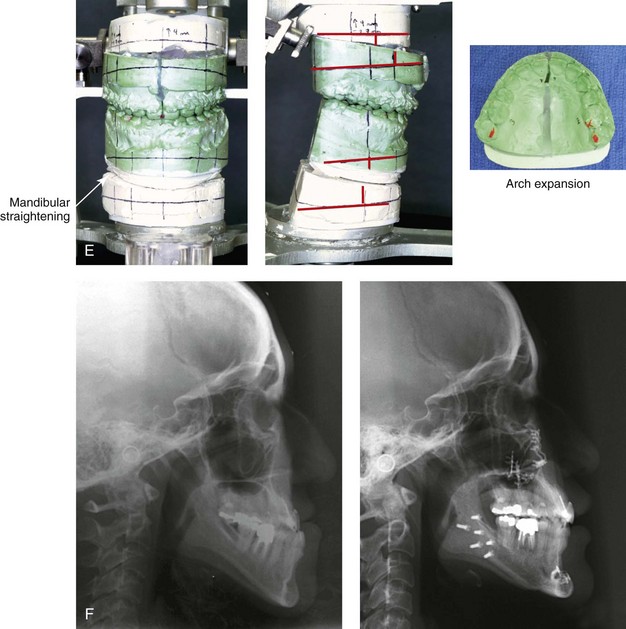

Figure 25-2 A woman in her early 50s was referred by a prosthodontist for surgical evaluation. There had been a gradual deterioration of her dentition that was at least partially a result of the longstanding Class II excess overjet deep-bite malocclusion. The head and neck evaluation confirmed a retrusive mandible, which also resulted in retroglossal airway obstruction. A desire for improved profile aesthetics was also discussed. A comprehensive approach to dental rehabilitation, improvement of the upper airway, and facial rejuvenation/reconstruction was chosen. Coordinated endodontic, orthodontic, periodontic, prosthodontic, and surgical care was required. Periodontal treatment, extractions, dental implant placement, restorative temporization, and orthodontic alignment were carried out. This was followed by surgery that included bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical lengthening) with interpositional grafting; and an anterior approach to the soft tissues of the neck (cervical flap elevation, neck defatting, and vertical platysma muscle plication). This was followed by crown lengthening and then by the final dental restorations. A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction/dental rehabilitation. B, Facial oblique views before and after reconstruction/dental rehabilitation. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction/dental rehabilitation. D, Occlusal views at presentation, before surgery, and after reconstruction/dental rehabilitation. E, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. F, Profile view of the chin. The intraoperative view of the chin osteotomy indicates vertical lengthening with hydroxyapatite interpositional bloc graft. G, Panorex radiographs before and after lower jaw and chin surgery with the placement of dental implants. H, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

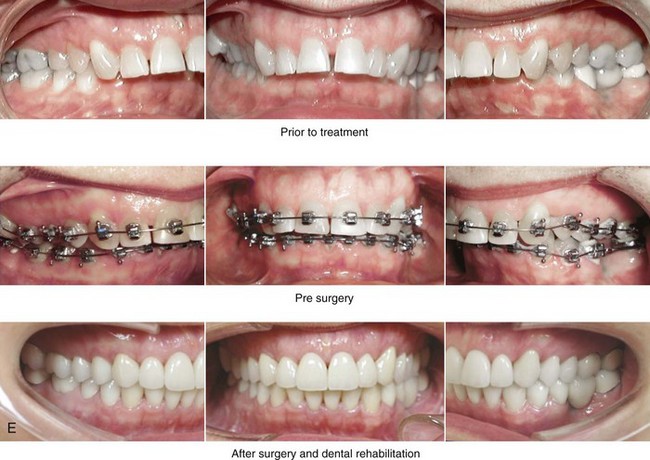

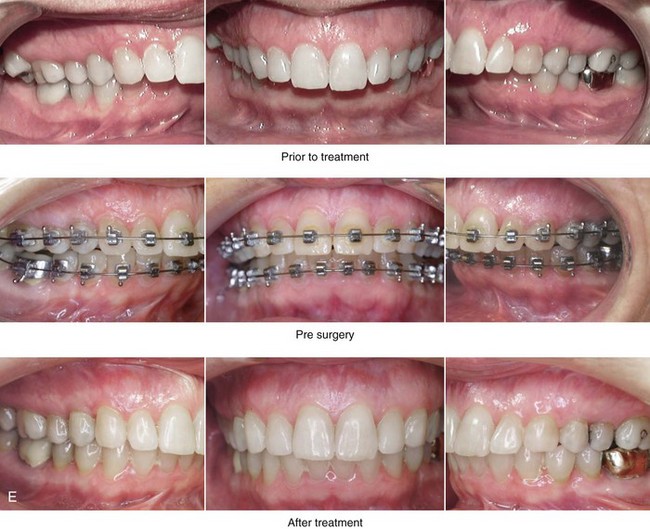

Figure 25-3 A woman in her late 40s with a long face growth pattern suffered deterioration of the dentition. Her periodontal risk factors included inadequate attached gingiva; dental root crowding within limited alveolar bone support, nasal airway obstruction with forced mouth breathing, and lip incompetence with drying of the exposed gingiva. An attended polysomnogram confirmed obstructive sleep apnea. Unfavorable soft-tissue envelope distortions and premature facial aging were also present. She agreed to a comprehensive surgical and dental rehabilitative approach. Periodontal treatment was followed by restorative temporization and orthodontic alignment, including four first bicuspid extractions. This was followed by surgery that included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (vertical shortening, horizontal advancement, transverse widening, and limited clockwise rotation); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and limited counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement); an anterior approach to the soft tissues of the neck (cervical flap elevation, neck defatting, and vertical platysma muscle plication); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. Note the pretreatment tendency for the patient to hyperextend her neck to achieve an improved airway. After successful surgery and with improved daytime breathing, her neck rests in a natural (neutral) position. E, Occlusal views before treatment and after reconstruction/dental rehabilitation. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment. Note the improved posterior airway space.

Figure 25-4 A woman in her mid 50s was experiencing significant dental deterioration as a result of occlusal trauma. An orthodontic consultation followed by surgical evaluation was carried out. The longstanding developmental jaw deformity was characterized by a short face growth pattern in combination with maxillary transverse constriction. There was a Class II deep-bite excess overjet malocclusion. The patient’s head and neck evaluation confirmed a lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing, restless sleeping at night, and a degree of daytime fatigue that was consistent with obstructive sleep apnea. Unfavorable facial aging that is typical of maxillomandibular deficiency was recognized. A comprehensive surgical and dental rehabilitative approach was selected. The objectives included dental rehabilitation, the enhancement of facial aesthetics, and an improved airway. The patient’s procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, vertical lengthening, and arch expansion); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement); osseous genioplasty (vertical lengthening and horizontal advancement); an anterior approach to the soft tissues of the neck (cervical flap elevation, neck defatting, and vertical platysma muscle plication); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction/dental rehabilitation. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction/dental rehabilitation. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction/dental rehabilitation. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction/dental rehabilitation. E, Occlusal views before treatment, with orthodontics in progress, and after reconstruction/dental rehabilitation. F, Articulated dental casts indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

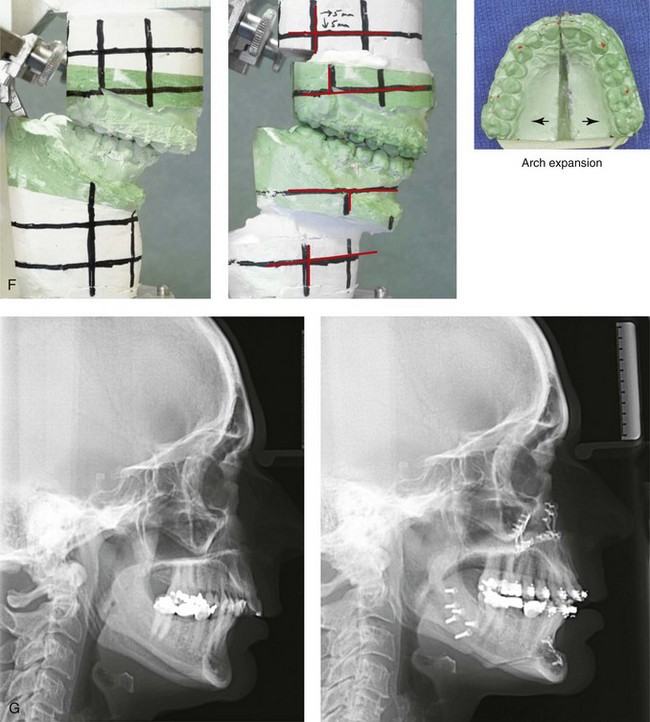

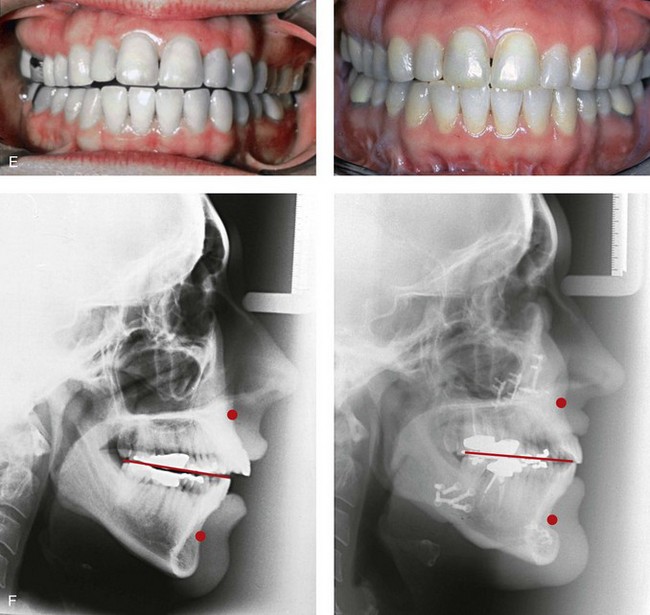

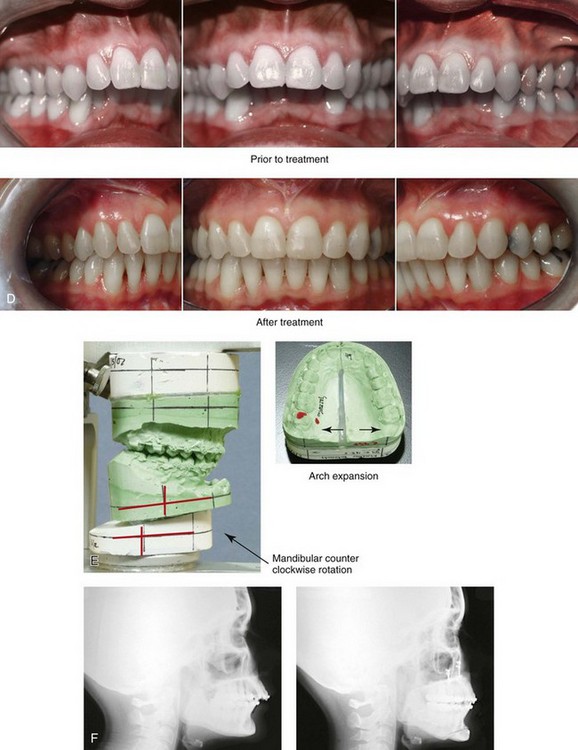

Figure 25-5 A woman in her early 40s wished to correct her malocclusion and improve her smile. She was referred to an orthodontist who then requested surgical evaluation. She was found to have a long face growth pattern and a lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing. There was dental crowding in each arch, mild gingival recession associated with the posterior dentition, and a Class II anterior open-bite malocclusion. The patient was aware of unfavorable facial aesthetics, which included a retrusive chin and an obtuse neck–chin angle. She agreed to a comprehensive surgical and dental rehabilitative approach. She underwent extraction of four bicuspids, orthodontic alignment, and then surgery. The patient’s procedures included Le Fort I osteotomy (vertical intrusion, horizontal advancement, and counterclockwise rotation); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement); an anterior approach to the neck (cervical flap elevation, neck defatting, and vertical platysma muscle plication); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before treatment, with extractions and orthodontic decompensation complete, and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after surgery.

Figure 25-6 A woman in her early 50s arrived for surgical evaluation and requested facial rejuvenation. Her head and neck examination confirmed a lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing and a long face growth pattern with gummy smile and lip incompetence. Unfavorable soft-tissue envelope facial aging added to the original dentofacial deformity. Early during her life, posterior occlusal equilibration was carried out to close down the anterior open bite; this resulted in dental deterioration that required crowns in the posterior dentition and the need for root canal therapy in many of the teeth. At this time, the patient agreed to a combined surgical and dental rehabilitation approach. After orthodontic preparation, the patient’s surgical procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (vertical intrusion, horizontal advancement, and counterclockwise rotation); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before and after treatment. F, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after surgery.

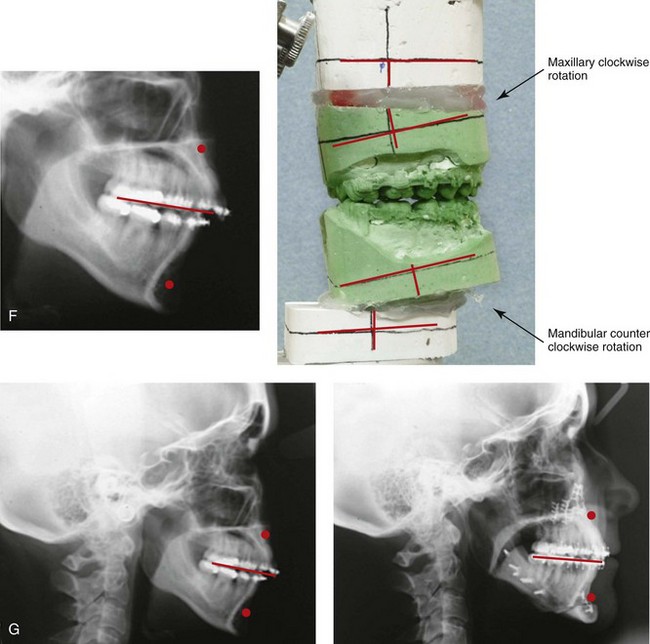

Figure 25-7 A woman in her mid 50s was seen by a prosthodontist for the management of a deteriorating posterior dentition. She was confirmed to have secondary dental trauma as a result of a longstanding malocclusion. She was referred to an orthodontist and then for surgical assessment. Her head and neck evaluation confirmed a short face growth pattern with a Class II excess overjet deep-bite constricted maxillary arch malocclusion. There was a lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing and the suggestion of obstructive sleep apnea, which was confirmed with an attended polysomnogram. Facial aesthetic concerns included the downturned corners of the mouth, the deep perioral creases, the early jowl formation, the weak profile, the obtuse neck–chin angle, and the loose skin of the neck. The patient agreed to a comprehensive surgical and dental rehabilitative approach. Periodontal evaluation, initial restorations, and orthodontic decompensation preceded surgery. The patient’s surgical procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement, counterclockwise rotation, and vertical adjustment); bilateral sagittal split osteotomies of the mandible (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); an anterior approach to the neck (cervical flap elevation, neck defatting, and vertical platysma muscle plication); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before treatment, with orthodontics in progress, and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment. Note the improved posterior airway space.

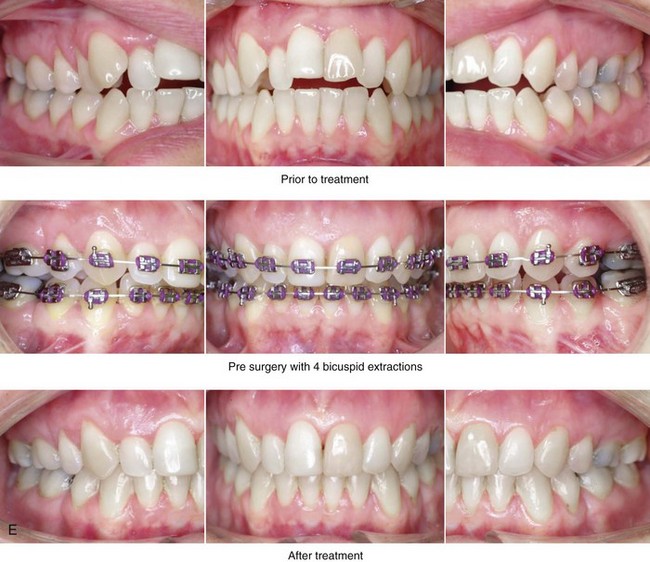

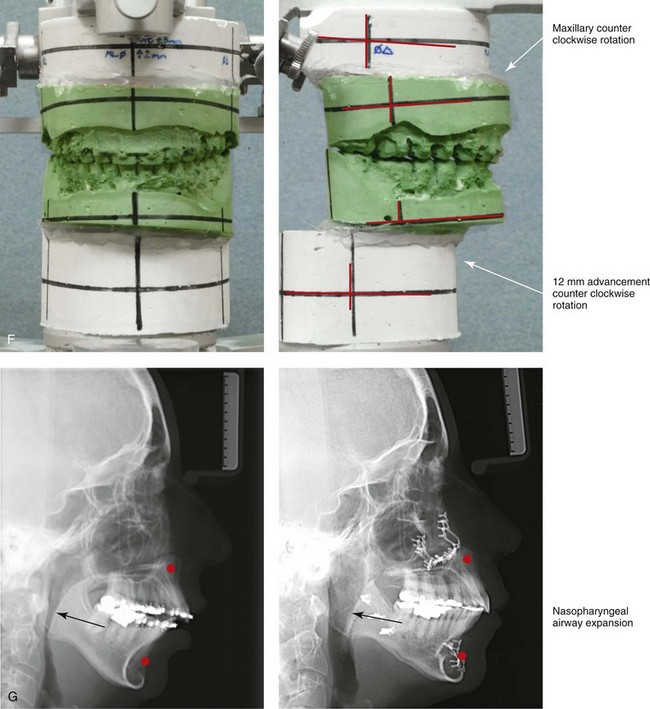

Figure 25-8 A woman in her mid 30s was referred by an orthodontist for surgical evaluation. She had a lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing and a long face growth pattern. Throughout her middle childhood and teenage years, she had undergone attempted growth modification followed by orthodontic camouflage that included four bicuspid extractions in an effort to neutralize the occlusion. This resulted in periodontal deterioration and dental relapse with residual malocclusion. She now agreed to a comprehensive surgical and dental rehabilitative approach. Periodontal treatment was followed by orthodontic decompensation. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, vertical shortening, counterclockwise rotation, arch expansion, and the correction of the curve of Spee); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies in segments (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction/dental rehabilitation. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction/dental rehabilitation. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction/dental rehabilitation. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction/dental rehabilitation. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, with orthodontics in progress, and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

Figure 25-9 A woman in her mid 40s requested the correction of her malocclusion and an improved smile. She was referred by a restorative dentist to an orthodontist and then for surgical evaluation. The developmental jaw deformity was characterized by mandibular deficiency in combination with maxillary arch width constriction. A lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing with a desire for an improved airway was also confirmed. A combined orthodontic and surgical approach was chosen. After orthodontic decompensation, the patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (transverse expansion); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Facial views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Occlusal views before treatment and after reconstruction. E, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. F, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

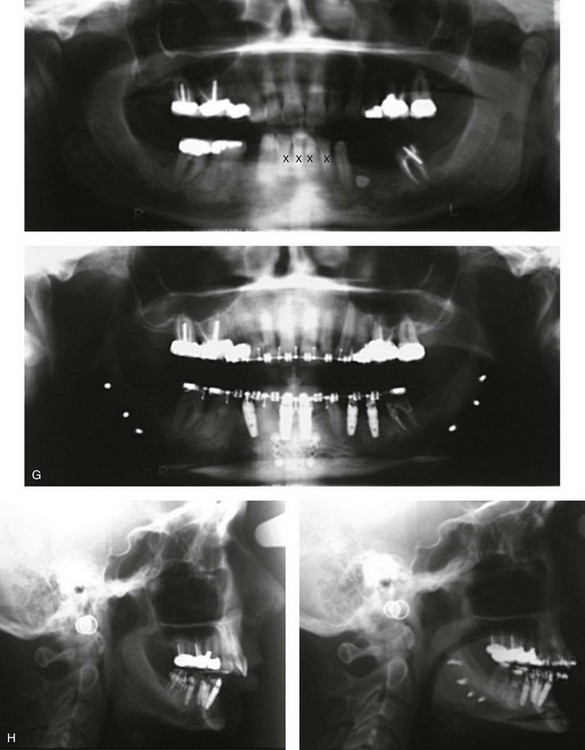

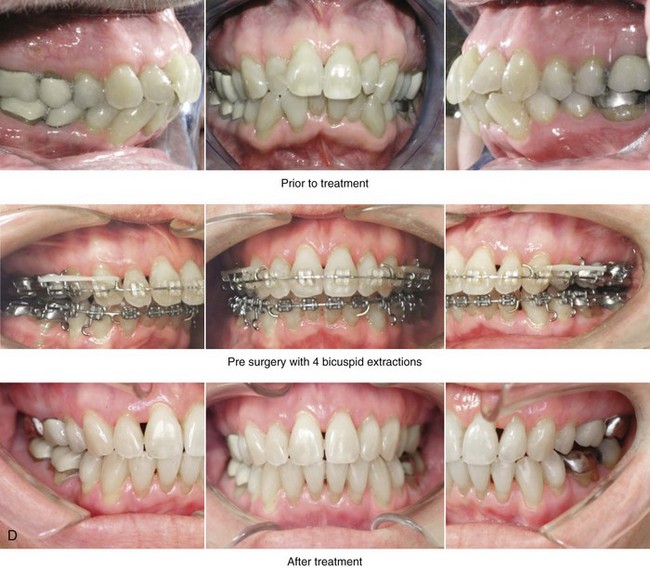

Figure 25-10 A 70-year-old woman arrived for surgical evaluation. She desired a stronger chin, less “loose” neck skin, and an improved smile. She initially requested a face lift and a chin implant. She was found to have a retrusive mandible and dental deterioration made worse by dental crowding and a deep-bite negative overjet malocclusion. She underwent orthodontics that included four bicuspid extractions and then surgery that included sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement) and osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement). A, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. B, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. C, Profile views before and after treatment. D, Occlusal views before treatment, with orthodontics in progress (including four bicuspid extractions), and after treatment. E, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. F, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after surgery.

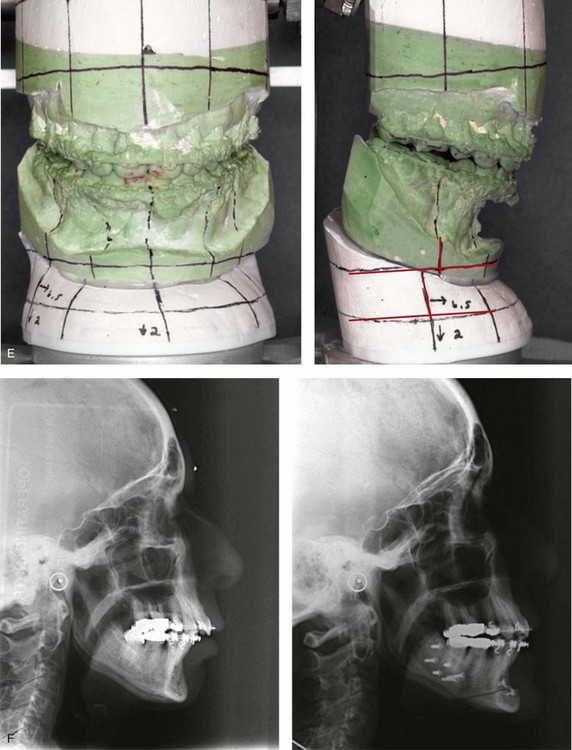

Figure 25-11 An Asian woman in her mid 30s had a developmental jaw deformity that was characterized by maxillary deficiency and relative mandibular excess. In the childhood years, she had been treated with growth modification followed by four bicuspid extractions and orthodontic camouflage mechanics. Periodontal deterioration resulted, and malocclusion remained. She also had a lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing. She now agreed to a comprehensive surgical and dental rehabilitative approach. Periodontal treatment was followed by orthodontic decompensation. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, vertical intrusion, counterclockwise rotation and transverse widening); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement); osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. B, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. C, Profile views before and after treatment. D, Occlusal views before retreatment, with orthodontics in progress, and after reconstruction/dental rehabilitation. E, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. F, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

Special Medical Considerations

For the adult who is more than 40 years old and who is considering orthognathic surgery, additional medical risk factors may include cardiovascular disease; the effects of obesity; smoking history and pulmonary function; the potential for deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolus; the effects of bisphosphonate medication on wound healing; and occult malignancy. As with teenagers and young adults, taking a thorough history, performing a review of the medical records, and completing a physical examination are essential. To clarify areas of concern in these patients, there should be emphasis placed on the need for a thorough clearance examination by a primary care physician; evaluations by other medical specialists; (e.g., cardiologist, pulmonologist); the completion of an electrocardiogram, chest radiography, and laboratory tests (e.g., chemistries, hematology, thyroid tests, coagulation tests); and other special studies (e.g., stress test, echocardiogram, sleep study, pulmonary function tests). Obtaining a hemoglobin A1C level and a serum or urine cotinine level are useful checks to address long-term diabetes effects and smoking compliance, respectively. The adult with a dentofacial deformity and an elevated body mass index is at risk for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and therefore more vulnerable to intraoperative and postoperative complications (see Chapter 26).

Functional Assessment of Head and Neck Structures

The orthognathic surgeon should evaluate the baseline head and neck functions of their patients, which include speech, swallowing, chewing, breathing, hearing, vision, cognition, and psychosocial competence (see Chapters 7 and 8). The documentation of cervical spine and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) baseline function and of any limitations in neck or mandibular range of motion is also essential (see Chapter 9). Each of these aspects may be negatively affected by the presenting maxillofacial malformations and influenced favorably or unfavorably by the treatment being contemplated. Baseline chronic obstructive nasal breathing as a result of septal deviation, enlarged inferior turbinates, or a tight nasal aperture should not be ignored (see Chapter 10).103,104,106,107 In the adult, weight gain with adipose hypertrophy within the upper airway in combination with hypotonia of the pharyngeal muscles in the presence of an uncorrected dentofacial deformity is likely to result in OSA. A formal attended polysomnogram, a complete upper airway evaluation, and a consultation with a sleep specialist are frequently indicated (see Chapter 26).

Temporomandibular Disorders: Effects of Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

It is estimated that an average of 32% of the population report at least one symptom of temporomandibular disorder (TMD) and that an average of 55% demonstrate at least one clinical sign of such a condition.117 TMDs include various symptoms and signs of the TMJs, the masticatory muscles, and the related structures. The symptoms and signs may include a spectrum of referred head and neck discomforts; joint noise (e.g., popping, clicking, crepitus); reduced or altered mandibular movements as a result of muscle spasm or disc displacement with or without reduction; condylar head erosion; and pain on direct palpation of either TMJ or of the masticatory muscles.

The effects of orthodontics and orthognathic surgery on TMJ function for each specific adult patient cannot be fully predicted. Many clinical studies report improvement in TMJ symptoms and signs in a majority of individuals after successful orthodontics and orthognathic surgery, although some patients will deteriorate after the procedures. The favorable TMJ effects of orthognathic surgery often observed in patients with preoperative TMD may be the result of the improved occlusion, the restoration of normal facial height and jaw projection, or the reduced emotional stress. Adults with longstanding TMD should be cautioned that their pretreatment findings may not respond to occlusal correction and jaw-straightening surgery. Baseline TMD problems in the patient with a dentofacial may primarily be masticatory muscle disorders (i.e., myofascial conditions) or, less commonly, the result of joint pathology (i.e., internal derangement). These two problems may coexist, and the distinction in some individuals may be difficult. It is unlikely that the correction of an existing dentofacial deformity will correct either internal joint problems or other non-muscular sources of pain. Myofascial pain develops when muscles are fatigued, because they then tend to go into spasm. Myofascial pain generally occurs after clenching or grinding the teeth for many hours each day, presumably as a response to stress. It is also true that some types of occlusal discrepancies predispose the individual who clenches or grinds his or her teeth to TMD. A compelling argument against malocclusion as the primary cause of TMD is the observation that TMD is not more prevalent among individuals with malocclusion as compared with those with a more normal occlusion. Interestingly, for those individuals with myofascial pain, the orthodontic mechanics required as part of the orthognathic correction are often helpful. This is because orthodontic treatment makes the teeth sensitive, which tends to limit grinding and clenching. Therefore, when the parafunctional (i.e. clenching, grinding) activity stops, the myofascial pain is often diminished. The changing occlusal relationships during the orthodontic phase of treatment may also contribute to a break in the cycle that contributed to the initial muscle fatigue and pain. The cycle of clenching and grinding is also broken during the healing phase that takes place just after orthognathic surgery. Unfortunately, it is also recognized that, at some point after successful orthodontics and orthognathic surgery, the individual with a long history of myofascial TMD symptoms may return to the clenching and grinding parafunctional habits. The use of an intra-occlusal splint in this situation will often be the best way to break the cycle and keep symptoms at bay. For all of these reasons, the individual’s rationale for the correction of the jaw deformity and the associated malocclusion should not be solely based on a desire for the permanent relief of TMJ symptoms and signs (see Chapters 7 and 9).

Special Wound Healing Risk Factors

Special wound healing risk factors may include previous radiation therapy, diabetes mellitus, smoking or other forms of nicotine use, and past or current bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis. Diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, and OSA are frequent comorbidities of obesity that may complicate wound healing. A significant incidence of postoperative infections among diabetic patients undergoing maxillary or mandibular osteotomies has been reported, despite adequately controlled glucose levels. The inhalation of nicotine via cigarette smoke affects pulmonary function as well as tissue oxygenation and the healing of the surgical wounds. Smoking (nicotine ingestion) has been shown to delay the chondrogenic phase of bone (osteotomy) healing, thereby negatively affecting the circulation of elevated flaps and their healing after wound closure. It is known that bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis affects osteoclastic activity and may negatively affect bone healing (see Chapter 16).

Comprehensive Dental Rehabilitation

Recognizing when a patient who is seeking orthognathic surgery has additional dental needs beyond standard orthodontics is essential to the achievement of a favorable outcome (see Figs. 25-1 through 25-11). The need for periodontal evaluation and treatment as well as the need for complex dental restorative work should be considered for every adult patient before the initiation of a coordinated orthodontic and jaw surgical approach. This is especially true for the adult who has suffered dental and periodontal sequelae from a longstanding uncorrected dentofacial deformity and who may have undergone camouflage treatment in an attempt to neutralize the occlusion (e.g., orthodontics, occlusal equilibration, restorative dentistry). The American Board of Orthodontics now requires evidence of the pretreatment periodontal condition for all adult patients.49 Proceeding with surgical and orthodontic management in an adult without considering a comprehensive dental rehabilitation plan is discouraged and only undertaken with full disclosure to the patient and discussion among the treating clinicians (see Chapters 6 and 16).

Unique Orthodontic Treatment Considerations

There has been a continuous increase in the number of adults seeking orthodontic treatment in North America as well as throughout Europe, South America, and the Asian countries. There is a worldwide increase in facial aesthetic awareness and a desire to maintain the dentition throughout life. The orthodontic movement of teeth in adults has potential effects on the periodontium that depend on the level of orthodontic force; the adequacy of alveolar bone and mucogingival tissue; and the presence of active periodontal disease (see Chapters 5 and 6). With aging, there may be progressive change of the periodontium with an increase in the crown-to-root ratio; a decrease in the resistance to spontaneous tooth migration; and a change in the center of resistance of periodontally affected teeth. The initial response of the periodontal ligament and the alveolar bone to orthodontic loading in the adult may be delayed; however, after tooth displacement has started, it can be carried out in the same way as it is for a teenager or a young adult. Although there is no known age limit to the orthodontic movement of teeth, the periodontium should be healthy when tooth movement is initiated.

As compared with a teenager, a middle-aged adult (i.e., someone >40 years old) with an uncorrected jaw deformity often requests a timely solution to his or her jaw, dental, and airway problems. Interestingly, the anticipation of an extended orthodontic treatment timeframe may be this patient’s greatest personal deterrent to proceeding. The adult is also more likely to present with advanced periodontal disease; dental migration and defective areas; traumatic occlusal problems; dental ankylosis; and the presence of fixed dental elements (e.g., titanium implants). These factors, by definition, will alter orthodontic mechanics. Contemporary orthodontic now offers a spectrum of options to improve the efficiency of treatment, including the use of light continuous forces; computer-aided design of orthodontic devices (e.g., Sure Smile, Insignia); and the regional acceleratory phenomena as described by Wilko and Wilko (see Chapter 5). These options must be viewed in light of their potential risks, complications, and costs (see Chapter 5).

Previous Suboptimal Facial Surgery

It is not uncommon to see an adult with an uncorrected dentofacial deformity who has undergone facial cosmetic procedures in an attempt to camouflage aesthetic concerns.4,31,132–136 In the individual with an uncorrected jaw deformity, the most commonly seen camouflage procedures include reduction rhinoplasty; a chin implant; cheek implants; and, to a lesser degree, angle of the mandible or perinasal implants.13,27,34,46,59,79,87,88,110,111,129,137,139 Autogenous and allogenic soft-tissue fillers and Botox injections (e.g., to lower the upper lip and to decrease a gummy smile) are also frequently tried.

A rhinoplasty carried out in the patient with an uncorrected jaw deformity patient is often over-reduced in an attempt to “shrink” the nose. This is most frequently seen in association with a horizontally retrusive lower face (e.g., short face growth pattern, long face growth pattern, isolated mandibular deficiency; see Chapters 19, 21, and 23). There may have been over-reduction of the nasal dorsum (i.e., bone and cartilage), over-resection of the lower lateral cartilages, and excess narrowing of the nasal base (i.e., Weir excisions; see Chapter 38). A reduction in nasal airflow as a result of the collapse of the internal or external nasal valves may have been an unanticipated side effect (see Chapter 10).

A chin implant placed in the patient with a mandibular deficiency often adds excess horizontal projection without addressing the vertical deformity; this will result in a deepened labiomental crease and an overly prominent pogonion (see Chapter 37). In the individual with a long face Class II open-bite growth pattern, the placement of a standard chin implant (i.e., without shortening the vertical chin height) further increases mentalis strain. Resorption of the bone below the implant and excess stretching of the overlying soft tissues with capsule formation may also occur. This is more frequently seen with the use of non-porous implant materials (e.g., Silastic) and when the implant is not secured in a stable manner (e.g., screw fixation) to the underlying bone (see Chapter 37). These failed camouflage surgical procedures further complicate plans for an anatomic reconstruction and effective facial rejuvenation.

Facial Aging and Rejuvenation

Background

The visual appearance of facial aging may be affected by all tissue layers and cell types, including the surface layer of the skin; the subcutaneous tissue; the superficial and deep mimetic muscles and the investing fascia (i.e., the submuscular aponeurotic system); the superficial and deep adipose tissue; and the retaining ligaments that connect the soft tissues to the skeleton and that separate them into compartments.10,14,18,67,85,90,114 Although facial aging is visualized through the soft-tissue envelope, it is profoundly affected by the underlying maxillomandibular skeletal structures. Soft-tissue facial rejuvenation procedures generally focus on the following:

1. The elevation, redraping, and excision of the skin, the subcutaneous tissue, and the submuscular aponeurotic system and platysma layer. This is to correct gravitational (descent) changes that have occurred over time.

2. The management of the volumetric changes of adipose tissue that occur with age. This includes compartment-specific depletion (deflation), hypertrophy (expansion) of the fat cells, and stretching of the retaining ligaments that then affect the facial contours and curvatures.*

3. The management of the surface layer of the skin. This layer is affected by both hereditary (genetic) and environmental factors (e.g., chronic exposure to strong ultraviolet light, nicotine/cigarette smoke, dehydration, nutritional deficiencies, temperature extremes, traumatic influences).15,16,20,23,45,72,78,93,138

4. The consideration of expressive muscle alteration with age (i.e., the “facial recurve” concept). Ligamental relaxation may be a prominent component of facial aging. For example, it may be responsible for malar descent in the midface. In the nasal region, “tip drooping” may be caused by ligament loosening of the lower lateral cartilage and clockwise rotation of the columella.124

An important morphologic fact is that, in the presence of a baseline uncorrected developmental dentofacial deformity, the overlying soft-tissue envelope will be distorted and less attractive (see Figs. 25-1 through 25-11).103,115,145 The longstanding skeletal dysmorphology will likely be responsible for a majority of the patient’s concerns about premature and unfavorable facial aging. An example of this phenomenon is seen in patients with the short face growth pattern (see Chapter 23). With age, the decreased lower anterior facial height and the diminished horizontal projection associated with this condition result in the premature loss of a youthful appearance (see Fig. 40-1). There will be accentuated perioral creases (i.e., marionette lines), early and excessive jowl formation, loose skin in the neck (i.e., a “turkey gobble” appearance), and a further worsening of the already deficient neck–jaw angle. Reconstruction of this pattern of dentofacial deformity in the adult to reflect Euclidean proportions is likely to have a profound rejuvenating effect (see Chapter 23).

The usual modus operandi of the cosmetic surgeon who has been asked to manage facial aging in the individual with a baseline dentofacial deformity involves neck and cheek soft-tissue flap undermining, redraping, and then the excision of skin that is under tension in the horizontal and vertical planes; this is also known as a face lift.5,6,8,52,53,56,57,83,108,125,128,130 Augmentation implants may be considered and occasionally placed (e.g., the chin, the angle of the mandible, the cheek, the pyriform rim) in an attempt to modify underlying skeletal deficiencies.13,27,34,46,59,60,79,87,88,137,139 In most cases, this approach predictably makes the face look different but not youthful or attractive. A natural-appearing rejuvenation in the adult with a dentofacial deformity requires reconstructing the normal curves and contours to the skeleton; these changes will then be favorably reflected in the overlying soft-tissue envelope. This is most naturally accomplished through orthognathic procedures that restore Euclidian proportions to the maxillomandibular complex.22,44,103,105,112,113,115,118

It is also true that facial aging—even in the presence of a proportionate skeleton—tends to gradually result in a transition from a heart-shaped face to a rectangular and then a pear-shaped face as gravity-induced descent and anterior drift of the soft-tissue envelope occur from the malar region superiorly through the nasolabial fold and from the submalar region to the jowls. At some point, as the individual ages, ideal rejuvenation is likely to require restoration of the lax and altered soft-tissue envelope, possibly via a brow lift, an eye lift, and a face lift. Fat volume redistribution frequently occurs with age (e.g., atrophy, hypertrophy) and may also benefit from rejuvenation procedures.3,21,29,30,32,50,61,64,65,73,77,81,82,86 The surface layer of the skin may have weathered with age and be improved with quality skin care or resurfacing procedures (e.g., chemical peels, laser treatments, dermabrasion; see Chapter 40).15,16,20,23,45,72,78,93,138

The term reconstruct can be defined as “to bring to normal.” The term rejuvenate means “to restore the look of the individual at a younger age.” In the adult with a baseline dentofacial deformity, the creation of normal facial curvatures—first through skeletal reconstruction and then via soft-tissue rejuvenation procedures—is required to fully capture the appearance of health, vitality and beauty. If successful, the enhancement of facial appearance will be immediately obvious for all to see without the need for quantitative analytic assessment. The maxillofacial surgeon has a unique opportunity to reconstruct the skeletal structures and to rejuvenate the soft tissues of the adult with an uncorrected dentofacial deformity. Attention is also focused on the rehabilitation of the dentition and the periodontium and on the achievement of a more functional upper airway. Adults with dentofacial deformities who undergo successful orthognathic surgery will experience a quantum change: they will look younger and better as compared with how they looked earlier during their lives. A variety of reactions from the patient’s social network are to be expected; these will range from positive responses to surprise, bewilderment, and even resentment. The individual’s response to these initial reactions will depend on his or her personality type, preoperative preparation, and inner ego stability (see Chapter 7).

Periorbital and Midface Aging

Most cosmetic surgeons focus on the soft tissues when they are considering options for the management of periorbital and midface aging.1,2,9,19,24,26,33,39,42,51,54,55,119 The traditional approach to aging in this region of the face focuses on the management of the laxity of the soft-tissue envelope and the reduction of protruding lower eyelid fat bags.40,47,80,116 The spectrum of current theories of periorbital and midface aging as well as methods of management are varied and have strong advocates, including the following.

1. Lambros has demonstrated through longitudinal photographic imaging that descent probably does not have as large a role in the aging process as previously thought.66

2. Coleman believes that the role of fat atrophy with volume loss and secondary sagging of the soft-tissue envelope is critical.25

3. Gosain evaluated changes in the cheek fat pad with aging through magnetic resonance imaging and found a combination of hypertrophy and ptosis (rather than atrophy) to be an important factor.48,150–152

4. Le Louarn postulates that the facial mimetic muscles are a predominant cause of the visual appearance of aging in the midface. He believes that repeated motion (i.e., contraction) of these muscles results in the redistribution of the facial fat over time, which eventually creates the aged face.69

5. Jelks has drawn attention to the importance of the anatomic relationship between the ocular globe, the periorbital soft tissues, and the underlying skeleton with respect to midface aging.62,63 A positive relationship (i.e., a positive vector) is said to exist when the most anterior projection of the globe in profile lies behind the lower eyelid margin.91 A negative relationship (i.e., a negative vector) exists when the most anterior projection the globe in profile lies anterior to the lower lid. Individuals with a negative vector relationship are more likely to have scleral show, to exhibit an apparent loss of cheek prominence, and to have a deep nasojugal groove. They are also prone to suboptimal results if traditional soft-tissue eyelid rejuvenation procedures are carried out. To achieve the most favorable result, the underlying skeletal deficiency and the lower lid laxity (i.e., lateral canthopexy) should also be addressed.

6. Pessa and colleagues agree with Jelks that skeletal deficiency is responsible for the negative vector relationship documented in adults with unattractive periorbital and midface aging.95–101 These authors postulate that, with age, the infraorbital rims partially resorb and regress posterior relative to the cornea. They also believe that, with age, the upper aspect of the anterior maxilla is partially resorbed with progressive curve distortion (i.e., concavity). They infer that, to achieve the most favorable result, the underlying skeletal deficiency must be addressed.

7. In his analysis of periorbital and midface aging, Yaremchuk agrees with Jelks and Pessa that the negative affects of aging in the periorbital midface region are greatly influenced by the underlying skeleton.140–149 He believes that a key element for attractive midface rejuvenation is reconstructing the skeleton to achieve convexity and a positive vector relationship. He accomplishes this via augmentation of the zygoma, the infraorbital rim, the anterior maxilla, and the base of the nose, as indicated. He frequently combines skeletal enhancement with lower lid and midface soft-tissue suspension to create and restore youthful and attractive periorbital aesthetics.

Consideration of Craniofacial Morphologic Change with Age: Does it Occur?

Although it has been much discussed, there is little convincing evidence to suggest that the craniofacial skeletal structures either significantly atrophy or hypertrophy with age after traditional growth maturity is reached.11,12,17,28,35–38,43,68,84,89,92,109,120,126,127,153 This should not be confused with the documented facial changes that do occur in association with the loss of teeth; occlusal surface erosion; the ongoing eruption of teeth; and disease of the periodontium. With extensive dental loss, significant deterioration of the horizontal projection, the vertical height, and transverse width of the midface and the lower face will unquestionably alter the soft-tissue drape and result in a more aged look. After skeletal maturity is reached (i.e., 14 to 16 years of age in girls and 16 to 18 years of age in boy) and in the absence of dental loss or significant deterioration, neither notable atrophy nor hypertrophy of the craniofacial prominences has been convincingly proven to occur. This specifically includes the following structures:

• The nasal height and the frontonasal angle

• The pyriform rims and the anterior nasal spine

Midface Skeletal Change with Age: Does it Occur?

In 1927, Hellman proposed the theory that the facial skeleton continues to grow throughout life58; he called this process morphological differentiation. Pessa and colleagues proposed an algorithm of facial aging to support Hellman’s theory on the basis of the review of a limited number of radiographs that suggested to him that bony changes of the midface (i.e., the zygoma and the infraorbital rim) occurred with age.95 The data that were used to support this theory were collected from computed tomography scans performed on just 12 men: six with a mean age of 20 years and six with a mean age of 56 years. These scans were not obtained for the same individuals over time, and they were not selected in a controlled fashion. Pessa made four difficult-to-reproduce angular measurements in each midface region on each scan (i.e., the glabellar angle, the orbital angle, the pyriform angle, and the angle of the maxillary wall). He concluded from the limited data that “the craniofacial skeleton continues to change with age resulting in remodeling of the maxilla [clockwise rotation] relative to the cranial base.”95 Despite Pessa’s theory, no scientific data confirm significant changes in the midface skeleton with age.

Levine and colleagues have also found fault with the “skeletal-aged” theories of Pessa and colleagues.70,71 They contend that Pessa’s theory of midface skeletal atrophy with age is based on an unsound interpretation of data from a limited number of non-longitudinal computed tomography scans and that it is not consistent with clinical observations or available research. Levine does believe that, in the presence of maxillary deficiency, soft-tissue descent and volume loss with age lead to the frequently observed unattractive changes seen in the midface periorbital region. He goes on to state that the negative vector relationship of the ocular globe and the lower eyelid in this subgroup of adults is more likely the result of a longstanding horizontal (sagittal) maxillary hypoplasia that has been present since the teenage years. It is the longstanding developmental midface skeletal deficiency that does not provide adequate support for the overlying soft tissues.41 As a result, retaining ligaments eventually give way, the fat may then atrophy or protrude, and the skin becomes lax.

Whether the negative vector eyelid aging characteristics (i.e., rounding of the palpebral fissure, lengthening of the lower lid, and loss of cheek prominence) results from a developmental skeletal midface hypoplasia or from skeletal atrophy with continued aging, most informed clinicians agree that the correction of the baseline bony deficiency is a key aspect of a natural-appearing rejuvenation. Yaremchuk’s analysis and clinical results are convincing evidence that the underlying skeleton is often where attention should be directed if effective rejuvenation is desired.141–149 Free fat grafting, the injection of various fillers, and the redistribution of the midface and lower lid soft tissues have more limited roles in the presence of a deficient skeletal framework. Too much attention given to the soft tissues or to imprecise skeletal augmentation will predictably result in an operated look that is visually obvious for all to see.

Mandibular Skeletal Change with Age: Does it Occur?

Pessa and colleagues also hypothesized that the mandible changes in shape during the aging process after normal skeletal maturity.98 The authors tested this theory in just 16 subjects (eight male subjects and eight female subjects) with the use of acetate tracings of frontal (posteroanterior) cephalograms taken during two different time frames. The first group ranged in age from 5 to 17 years, and the second group ranged in age from 46 to 60 years. Seven difficult-to-reproduce data points were chosen along the inferior border of the mandible on each radiograph; an analysis was carried out with the use of these points. From this data, the authors theorized that the “youthful mandible had a greater degree or curvature whereas the mature [middle-aged] mandible can be described as having a less convex curvature” and that “the mandible increases in size [length] with continued growth.” A critical review of Pessa’s methods suggests that the posteroanterior cephalometric radiographs of the young study subjects were not standardized for head position (i.e., flexion and extension) as compared with the radiographs taken of the older subjects. Therefore, the accuracy of the comparison measurements taken along the inferior border of the mandible on each of the non-longitudinal radiographs is questionable. This inaccuracy is caused by inherent distortions that result from differences of positioning of the subjects’ heads at the time that the two-dimensional radiographs were taken.

Shaw and colleagues recently reviewed computed tomography scans of dentate Caucasian subjects; they included an equal number of women (n = 60) and men (n = 60) in an attempt to identify changes in mandibular morphology with age.121 The patient population was not evaluated longitudinally, and it was not standardized. The radiographs were taken from a hospital-based data pool and not controlled to exclude those with jaw deformities, significant malocclusions, congenital anomalies, or trauma. The researchers further subdivided the radiographs into three groups in accordance with the age brackets of the patients (i.e., 20 to 40 years, 41 to 64 years, and >65 years). The authors took measurements from each scan related to the width and length of the mandible and at the gonial angles. Interestingly, the authors drew conclusions from these data that are contradictory to those of published studies carried out by other investigators with the similar intention of clarifying the effects of age on mandibular morphology. For example, the study by Pecora and colleagues suggests that the mandible continues to grow in length in both men and women during aging.94 Pessa and colleagues also suggest that there is an increase in mandibular width, height, and length with aging. The analysis by Bartlett and colleagues of postmortem human skull data suggest that there is an increase in the width—but not the length—of the mandible with age.7

Recovery in the Adult after Orthognathic Surgery

Setting Clear Objectives with Realistic Expectations

All parties involved should agree on the treatment objectives and accept the risks and limitations of the planned surgical procedures. Unfortunately, the patient’s preoperative psychosocial assessment, the surgeon’s understanding of unique wound healing requirements, and the uncertainties of surgery are not completely predictable. Furthermore, orthognathic surgery should not be carried out with a belief that it will repair broken personal relationships, save jobs, or overcome financial concerns. The reality is that a small percentage of patients will perceive an unfavorable surgical outcome even when the clinicians feel that the results are at least satisfactory. Others will not accept a complication even though the risks were explained in advance and all reasonable precautions were taken. Experience has shown that there are no shortcuts to thorough patient education; comprehensive care must be provided every step of the way (see Chapter 7).

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

To minimize patient disappointment after surgery, an informal (and, in some cases, a more rigorous) psychosocial assessment is indicated. The clinician must keep in mind that some individuals who are seeking treatment will have a true psychiatric disorder. Body dysmorphic disorder is a medical condition that can be difficult for a clinician to recognize before surgery. If this condition is present, it will be a predictable cause of unhappiness after surgery. It is estimated that 7% to 15% of individuals who are pursuing cosmetic surgery may have body dysmorphic disorder (see Chapter 7).

Sensory Loss and Incidence of Dysesthesia

Inferior Alveolar and Mental Nerve Injury and Recovery

During sagittal split ramus osteotomies of the mandible, the inferior alveolar nerve can be directly damaged by a burr on a rotary drill, a blade on a reciprocating saw, or a chisel used to complete the split. The nerve can also be compressed during osteotomy stabilization (i.e., plate and screw fixation). Studies document that, with time, inferior alveolar nerve sensory function is generally sufficient in most patients, although complete recovery is uncommon. The exact reasons why, over time, most patients experience only a degree of simple loss of sensation in the distribution of the inferior alveolar nerve, some continue to experience active sensations that are not normally present but are of little concern, and a small percentage have active sensations that are subjectively uncomfortable or painful (i.e., dysesthesia) is not known. Zuniga and colleagues (see chapter 16) report a 5% incidence of dysesthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve after sagittal split ramus osteotomy (see Chapter 16 for a more complete review of the literature).

Infraorbital Nerve Injury and Recovery

A degree of injury to the infraorbital nerve at the time of Le Fort I osteotomy that results in paresthesia is expected, whereas long-term dysesthesia of the cheek skin, the upper lip, the palatal mucosa, and the gingiva is less common. Infraorbital nerve injury may result from compression, stretching, or direct injury from saw blades, burs, or handheld instruments. A study by Thygesen and colleagues (see Chapter 16) found continued changes (i.e., less than full recovery had occurred) in somatosensory infraorbital nerve function 12 months after Le Fort I osteotomy in 7% to 60% of patients. This included the regions of the cutaneous skin, the lip, the gingiva, and the palatal mucosa. Fortunately, the authors did not find instances of significant dysesthesia associated with the documented sensory loss in any of the study patients (see Chapter 16 for a more complete review of the literature).

Patient Age and Sensory Recovery

It is believed that older patients (i.e., >25 years old and especially >40 years old) who sustain the same extent of injury to either the infraorbital nerve or the inferior alveolar nerve after maxillary or mandibular osteotomies, respectively, will not experience the same degree of subjective sensory recovery as younger individuals. It appears that the time required for “acceptable” subjective recovery of facial and oral sensation is longer and that the percentage of middle-aged adults who have undergone these operations and who interpret their lack of full sensory return as dysesthesia (i.e., uncomfortable sensory loss) is higher than that observed among teenagers and young adults (see Chapter 16). Adults are more likely to complain about a lack of sensory return to the mucosa of the palate and the gingiva. They may be annoyed by the lack of proprioception when flossing and when managing food on the roof of the mouth. Interestingly, Pogrel and colleagues documented that, with time, men tend to achieve a more tolerable decrease in these uncomfortable sensory symptoms than women.102

References

1. Aiache, AE, Ramirez, OH. The suborbicularis oculi fat pads: An anatomic and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995; 95:37.

2. Anderson, RD, Lo, MW. Endoscopic malar/midface suspension procedure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998; 102:2196.

3. Ascher, BA, Coleman, S, Alster, T, et al. Full scope of effect of facial lipoatrophy: A framework of disease understanding. Dermatol Surg. 2006; 32:1058–1069.

4. Bains, JW, Elia, JP. The role of facial skeletal augmentation and dental restoration in facial rejuvenation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1994; 18:243.

5. Baker, DC. Lateral SMASectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; 100:509–513.

6. Baker, T, Stuzin, J. Personal technique for facelifting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; 100:502–508.

7. Bartlett, SP, Grossman, R, Whitaker, LA. Age-related changes of the craniofacial skeleton: An anthropometric and histologic analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 90:592–600.

8. Barton, FE, Jr. Rhytidectomy and the nasolabial fold. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 90:601.

9. Barton, FE, Jr., Kenkel, JM. Direct fixation of the malar pad. Clin Plast Surg. 1997; 24:329.

10. Bass, NM. The aesthetic analysis of the face. Eur J Orthod. 1991; 13:343–350.

11. Behrents RG, ed. Growth in the aging craniofacial skeleton. Monograph No 17, Craniofacial Growth Series. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Center for Human Growth and Development, The University of Michigan, 1985.

12. Behrents, RG. An atlas of growth in the aging craniofacial skeleton. Monograph 18. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Center for Human Growth and Development, The University of Michigan; 1985.

13. Binder, WJ, Bloom, DC. The use of custom-designed midfacial and submalar implants in the treatment of facial wasting syndrome. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004; 6:394–397.

14. Bishara, SE, Jakobsen, JR, Hession, TJ, Treder, JE. Soft tissue profile changes from 5 to 45 years of age. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998; 114:698–706.

15. Bologna, JL. Dermatologic and cosmetic concerns of the older woman. Clin Geriatr Med. 1993; 9:209–229.

16. Brown, AM, Kaplan, ML, Brown, ME. Phenol-induced histological skin changes: Hazards, technique, and uses. Br J Plast Surg. 1960; 13:158.

17. Burr, DB. Muscle strength, bone mass, and age-related bone loss. J Bone Miner Res. 1997; 12:1547.

18. Burstone, CJ. The integumental profile. Am J Orthod. 1958; 44:1–25.

19. Byrd, HS, Andochick, SE. The deep temporal lift: A multiplanar, lateral brow, temporal, and upper face lift. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996; 97:928–937.

20. Carruthers, J, Fagien, S, Matarasso, SL, Botox Consensus Group. Consensus recommendations on the use of botulinum toxin type A in facial aesthetics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004; 114(Suppl):1–22.

21. Carruthers, JDA, Carruthers, A. Facial sculpting and tissue augmentation. Dermatol Surg. 2005; 31:1604–1612.

22. Chemello, PD, Wolford, LM, Buschang, PH. Occlusal plane alteration in orthognathic surgery—Part II: Long-term stability of results. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1994; 106:434–440.

23. Cheng, JT, Perkins, SW, Hamilton, MM. Collagen and injectable fillers. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2002; 35:73–85.

24. Chiu, ES, Baker, DC. Endoscopic brow lift: A retrospective review of 628 consecutive cases over 5 years. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003; 112:628–633.

25. Coleman, SR. Structural fat grafting: More than a permanent filler. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006; 118(3 Suppl):108S–120S.

26. Collawn, SS, Vasconez, LO, Gamboa, M, et al. Subcutaneous approach for elevation of the malar fat pad through a prehairline incision. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996; 97:836.

27. Constantinides, MS, Galli, SK, Miller, PJ, Adamson, PA. Malar, submalar, and midfacial implants. Facial Plast Surg. 2000; 16:35–44.

28. Daher, JC, Cosac, OM, Domingues, S. Face-lift: The importance of redefining facial contours through facial liposuction. Ann Plast Surg. 1988; 21:1.

29. Donofrio, LM. Fat distribution: A morphologic study of the aging face. Dermatol Surg. 2000; 26:1107–1112.

30. Donofrio, LM. Panfacial volume restoration with fat. Dermatol Surg. 2005; 31:1496–1505.

31. Ellenbogen, R, Motykie, G, Youn, A, et al. Facial reshaping using less invasive methods. Aesthet Surg J. 2005; 25:144–152.

32. Ersek, RA, Chang, P, Salisbury, MA. Lipo layering of autologous fat: An improved technique with promising results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998; 101:820–826.

33. Finger, ER. Transmalar subperiosteal midface lift: Early results with a simplified approach. Aesthet Surg J. 1996; 16:261.

34. Flowers, RS. Tear trough implants for correction of tear trough deformity. Clin Plast Surg. 1993; 20:403.

35. Formby, WA. Longitudinal growth changes in the face from 18 to 42 years [master’s thesis]. Oklahoma City, Okla: The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center; 1991.

36. Frost, HM. Tetracycline-based histological analysis of bone remodeling. Calcif Tissue Int. 1969; 3:211.

37. Frost, HM. Changing concepts in skeletal physiology: Wolff’s Law, the mechanostat and the “Utah Paradigm. ”. J Hum Biol. 1998; 10:599.

38. Frost, HM. Perspective on the estrogen-bone relationship and postmenopausal bone loss: A new model. J Bone Miner Res. 1999; 14:1473.

39. Furnas, DW. Festoons, mounds, and bags of the eyelids and cheek. Clin Plast Surg. 1993; 20:367.

40. Goldberg, RA, Wu, JC, Jesmanowicz, A, Hyde, JS. Eyelid anatomy revisited: Dynamic high-resolution magnetic resonance images of Whitnall’s ligament and upper eyelid structures with the use of a surface coil. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992; 110:1598.

41. Goldberg, RA, Relan, A, Hoenig, J. Relationship of the eye to the bony orbit, with clinical correlations. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1999; 27:98.

42. Goldberg, RA. The three periorbital hollows: A paradigm for periorbital rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004; 116:1796–1804.

43. Goldstein, MS. Changes in dimensions and form of the face and head with age. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1936; 22:37–89.

44. Goncalves, JR, Bushang, PH, Goncalves, DG. Postsurgical stability of oropharyngeal airway changes following counterclockwise maxillo-mandibular advancement surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 64:755–762.

45. Gonzalez-Ulloa, M, Castillo, A, Stevens, E, et al. Preliminary study of the total restoration of the facial skin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1954; 13:151–161.

46. Gonzalez-Ulloa, M. Building out the malar prominences as an addition to rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974; 53:293.

47. Gosain, AK, Amarante, MTJ, Hyde, JS, Yousif, NJ. A dynamic analysis of changes in the nasolabial fold using magnetic resonance imaging: Implications for facial rejuvenation and facial animation surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996; 98:622.

48. Gosain, AK, Klein, MH, Sudhakar, PV, et al. A volumetric analysis of soft-tissue changes in the aging midface using high-resolution MRI: Implications for facial rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005; 115:1143–1152.

49. Grubb, JE, Greco, PM, English, JD, et al. Radiographic and periodontal requirements of the American Board of Orthodontics : a modification in the case display requirements for adult and periodontally involved adolescent and preadolescent patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008; 134:3–4.

50. Guerrerosantos, J. Long-term outcome of autologous fat transplantation in aesthetic facial recontouring: Sixteen years of experience with 1936 cases. Clin Plast Surg. 2000; 27:515–543.

51. Gunter, JP, Antrobus, SD. Aesthetic analysis of the eyebrows. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; 99:1808.

52. Hamra, ST. The deep-plane rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990; 86:53–61.

53. Hamra, ST. Composite rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 90:1.

54. Hamra, ST. Arcus marginalis release and orbital fat preservation in midface rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995; 96:354.

55. Hamra, ST. The role of orbital fat preservation in facial aesthetic surgery: A new concept. Clin Plast Surg. 1996; 23:17.

56. Hamra, ST. Frequent face lift sequelae: Hollow eyes and the lateral sweep: Cause and repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998; 102:1658.

57. Heinrichs, HL, Kaidi, A. Subperiosteal face lift: A 200-case, 4-year review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998; 102:843.

58. Hellman, M. Changes in the human face brought about by development. Int J Oral Surg Radiol. 1927; 20(37):463–465.

59. Hinderer, UT. Malar implants for the improvement of the facial appearance. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975; 56:157.

60. Hinderer, UT. Nasal base, maxillary and infraorbital implants—alloplastic. Clin Plast Surg. 1991; 18:87.

61. Jackson, IT. Buccal fat pad removal. Aesthet Surg J. 2003; 23:484–485.

62. Jelks, GW, Jelks, EB. The influence of orbital and eyelid anatomy on the palpebral aperture. Clin Plast Surg. 1991; 18:193–204.

63. Jelks, GW, Jelks, EB. Preoperative evaluation of the blepharoplasty patient: Bypassing the pitfalls. Clin Plast Surg. 1993; 20:213.

64. Kanchwala, SK, Bucky, LP. Facial fat grafting: The search for predictable results. Facial Plast Surg. 2003; 19:137.

65. Kanchwala, SK, Holloway, L, Bucky, LP. Reliable soft tissue augmentation: A clinical comparison of injectable soft tissue fillers for facial-volume augmentation. Ann Plast Surg. 2005; 55:30.

66. Lambros, V. Observations on periorbital and midface aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007; 120:1367–1376.

67. LaTrenta, GS. Atlas of aesthetic face and neck surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004.

68. Lavater, JC. Essays on physiognomy, Vol 1-3. London: J & J Robinson; 1789.

69. Le Louarn, C, Buthiau, D, Buis, J. Structural aging: The facial recurve concept. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2007; 31:213–218.

70. Levine, RA, Garza, JR, Wang, PTH, et al. Adult facial growth: Applications to aesthetic surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2003; 27:265–268.

71. Levine, RA. Letter. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008; 121:698.

72. Leyden, JJ. Clinical features of aging skin. Br J Dermatol. 1990; 122(Suppl):1.

73. Liang, M, Narayanan, K, Davis, PL, Futrell, JW. Evaluation of facial fat distribution using magnetic resonance imaging. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1991; 15:313–319.

74. Little, JW. Volumetric perceptions in midfacial aging with altered priorities for rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 105:252–266.

75. Little, JW. Three-dimensional rejuvenation of the midface: Volumetric resculpture by malar imbrication. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 105:267–285.

76. Loeb, R. Nasolabial fold undermining and fat grafting based on histologic study. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1991; 15:61.

77. Matarasso, A. Managing the buccal fat pad. Aesthet Surg J. 2006; 26:330–336.

78. Matarasso, SL, Carruthers, JD, Jewell, ML, et al. Consensus recommendations for soft tissue augmentation with non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid (Restylane). Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006; 117(Suppl):3S.

79. May, JW, Jr., Zenn, MR, Zingarelli, P. Subciliary malar augmentation and cheek advancement: A 6-year study on 22 patients undergoing blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995; 96:1553.

80. Mendelson, BC, Muzaffar, AR, Adams, WP, Jr. Surgical anatomy of the midcheek and malar mounds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002; 110:885–896.

81. Millard, DR, Pigott, RW, Hedo, A. Submandibular lipectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968; 41:513.

82. Millard, DR, Jr., Yuan, RT, Devine, JW, Jr. A challenge to the undefeated nasolabial folds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987; 80:37.

83. Miller, T. Face lift: Which technique? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; 100:501.

84. Mittleman, H. The anatomy of the aging mandible and its importance to facelift surgery. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 1994; 2:301–309.

85. Mitz, V, Peyronie, M. The superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976; 58:80–88.

86. Mladick, RA. Lipoplasty: An ideal adjunctive procedure for the face lift. Clin Plast Surg. 1989; 16:333.

87. Mladick, RA. Alloplastic cheek augmentation. Clin Plast Surg. 1991; 18:29.

88. Mole, B. The use of Gore-Tex implants in aesthetic surgery of the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 90:200–206.

89. Montagna, W, Carlisle, K. Structural changes in aging skin. Br J Dermatol. 1990; 122(Suppl 35):61–70.

90. Moss, CJ, Mendelson, BC, Taylor, GI. Surgical anatomy of the ligamentous attachments in the temple and periorbital regions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 105:1475–1490.

91. Mulliken, JB, Godwin, SL, Pracharktam, N, Altobelli, DE. The concept of sagittal orbital-globe relationship in craniofacial surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996; 97:700.

92. Nanda, RS. The rates of growth of several facial components measured from serial cephalometric roentgenograms. Am J Orthod. 1955; 41:658–665.

93. Oba, A, Edwards, C. Relationships between changes in mechanical properties of the skin, wrinkling, and destruction of dermal collagen fiber bundles caused by photoaging. Skin Res Technol. 2006; 12:283–288.

94. Pecora, NG, Baccetti, T, McNamara, JA, Jr. The aging craniofacial complex: A longitudinal cephalometric study from late adolescence to late adulthood. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006; 134:496–505.

95. Pessa, JE, Zadoo, VP, Mutimer, KL, et al. Relative maxillary retrusion as a natural consequence of aging: Combining skeletal and soft-tissue changes into an integrated model of midfacial aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998; 102:205–212.

96. Pessa, JE, Desvigne, LD, Lambros, VS, et al. Changes in ocular-to-orbital rim position with age: implications for aesthetic blepharoplasty of the lower eyelids. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1999; 23:337–342.

97. Pessa, JE, Peterson, ML, Thompson, JW, et al. Pyriform augmentation as an ancillary procedure in facial rejuvenation surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999; 103:683.

98. Pessa, JE, Zadoo, VP, Yuan, C, et al. Concertina effect and facial aging: Nonlinear aspects of youthfulness and skeletal remodeling, and why, perhaps, infants have jowls. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999; 103:635–644.

99. Pessa, JE. An algorithm of facial aging: Verification of Lambros’ theory by three-dimensional stereolithography, with reference to the pathogenesis of midfacial aging, scleral show, and the lateral suborbital trough deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 106:479–488.

100. Pessa, JE, Chen, Y. Curve analysis of the aging orbital aperture. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002; 109:756–760.

101. Pessa, JE. Reply. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008; 121:699.

102. Pogrel, MA, Jergensen, R, Burgon, E, Hulme, D. Long-term outcome of trigeminal nerve injuries related to dental treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:2284–2288.

103. Posnick, JC, Fantuzzo, J, Orchin, J. Deliberate operative rotation of the maxillo-mandibular complex to alter the A-point to B-point relationship for enhanced facial esthetics. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 64:1687–1695.

104. Posnick, JC, Fantuzzo, JJ, Troost, T. Simultaneous intranasal procedures to improve chronic obstructive nasal breathing in patients undergoing maxillary (Le Fort I) osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 65:2273–2281.

105. Posnick, JC, Wallace, J. Complex orthognathic surgery assessment of patient satisfaction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008; 66:934.

106. Posnick, JC, Agnihotri, N. Consequences and management of nasal airway obstruction in the dentofacial deformity patient. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010; 18:323–331.

107. Posnick, JC, Agnihotri, N. Managing chronic nasal airway obstruction at the time of orthognathic surgery: A twofer. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:695–701.

108. Psillakis, JM, Rumley, TO, Camargos, A. Subperiosteal approach as an improved concept for correction of the aging face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988; 82:383.

109. Raskin, E, LaTrenta, GS. Why do we age in our cheeks? Aesthet Surg J. 2007; 27:19–28.

110. Rees, T, Ashley, F. Treatment of facial atrophy with liquid silicone. Am J Surg. 1966; 111:531–535.

111. Rees, T, Ashley, F, Delgado, J. Silicone fluid injections for facial atrophy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972; 52:118–127.

112. Reyneke, JP, Evans, WG. Surgical manipulation of the occlusal plane. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1990; 5:99–110.

113. Reyneke, JP, Bryant, RS, Suuronen, R, Becker, PJ. Postoperative stability following clockwise and counter-clockwise rotation of the maxillomandibular complex compared to conventional orthognathic treatment. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 45:56–64.

114. Rogers, BO. A chronologic history of cosmetic surgery. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1971; 47:265–302.

115. Rosen, HM. Facial skeletal expansion: Treatment strategies and rationale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 89:798–808.

116. Rubin, LR, Mishriki, Y, Lee, G. Anatomy of the nasolabial fold: The keystone of the smiling mechanism. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989; 83:1.

117. Rugh, JD, Solberg, WK. Oral health status in the United States: Temporomandibular disorders. J Dent Educ. 1985; 49:399–405.

118. Sarver, DM, Rousso, DR. Plastic surgery combined with orthodontic and orthognathic procedures. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004; 126:305–307.

119. Sasaki, GH, Cohen, AT. Meloplication of the malar fat pads by percutaneous cable suture technique for midface rejuvenation: Outcome study (392 cases, 6 years’ experience). Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002; 110:635.

120. Schubert, P, Bailey, LJ, White, RP, Proffit, WR. Long-term cephalometric changes in untreated adults compared to those treated with orthognathic surgery. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1999; 14:91–99.

121. Shaw, RB, Kahn, DM. Aging of the midface bony elements: A three-dimensional computed tomographic study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007; 119:675–681.

122. Staten, MA, Totty, WV, Kohrt, WM. Measurements of fat distribution by magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol. 1989; 24:345.

123. Stuzin, JM, Wagstrom, L, Kawamoto, HK, et al. The anatomy and clinical implications of the buccal fat pad. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990; 85:29–37.

124. Stuzin, JM, Baker, TJ, Gordon, HL. The relationship of the superficial and deep facial fascias: Relevance to rhytidectomy and aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 89:441–451.

125. Stuzin, JM, Baker, TJ, Gordon, HL, Baker, TM. Extended SMAS dissection as an approach to midface rejuvenation. Clin Plast Surg. 1995; 22:295.

126. Tallgren, A. Neurocranial morphology and aging: A longitudinal roentgen cephalometric study of adult Finnish women. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1974; 41:285–294.

127. Tallgren, S, Solow, B. Long-term changes in hyoid position and craniocervical posture in complete denture wearers. J Dent Res. 1981; 60:473.

128. Teimourian, B. Face and neck suction-assisted lipectomy associated with rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983; 72:627.

129. Terino, EO. Alloplastic contouring in the malar-midface-middle third facial aesthetic unit. In: Terino EO, Flowers RS, eds. The art of alloplastic facial contouring. St Louis: Mosby, 2000.

130. Tessier, P. Subperiosteal face lift. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 1989; 34:193.

131. Trepsat, F. Volumetric face lifting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001; 108:1358.

132. Van der Dussen, FN, Egyedi, P. Premature aging of the face after orthognathic surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 1990; 18:335.

133. Whitaker, LA. Facial skeletal contouring for aesthetic purposes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982; 69:245.

134. Whitaker, LA. Aesthetic augmentation of the malar-midface structures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987; 90:337–341.

135. Whitaker, LA, Bartlett, SP. Skeletal alteration as a basis for facial rejuvenation. Clin Plast Surg. 1991; 18:197.

136. Whitaker, LA. Temporal and malar-zygomatic reduction and augmentation. Clin Plast Surg. 1991; 18:55.

137. Wilkinson, TS. Complications in aesthetic malar augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983; 71:643.

138. Wise, JB, Greco, TG. Injectable treatments for the aging face. Facial Plast Surg. 2006; 22:140–146.

139. Wolfe, SA. Malar augmentation using autogenous materials. Clin Plast Surg. 1991; 18:39.

140. Yaremchuk, MJ, Israeli, D. Paranasal implants for correction of midface concavity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998; 102:1676–1684.

141. Yaremchuk, MJ. Mandibular augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 106:697–706.

142. Yaremchuk, MJ. Infraorbital rim augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001; 107:1585–1592.

143. Yaremchuk, MJ. Subperiosteal and full-thickness skin rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001; 107:1045–1057.

144. Yaremchuk, MJ. Restoring palpebral fissure shape after previous lower blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003; 111:441–450.

145. Yaremchuk, MJ. Improving periorbital appearance in the “morphologically prone. ”. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004; 114:980–987.

146. Yaremchuk, MJ. Making concave faces convex. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2005; 29:141–147.

147. Yaremchuk, MJ. Indications, evaluation and planning. In: Yaremchuk MJ, ed. Atlas of facial implants. Philadelphia: Saunders-Elsevier; 2007:3–22.

148. Yaremchuk, MJ, Chen, YC. Enlarging the deficient mandible. Aesthet Surg J. 2007; 27:539–550.

149. Yaremchuk, MJ, Doumit, G, Thomas, MA. Alloplastic augmentation of the facial skeleton: An occasional adjunct or alternative to orthognathic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011; 127:2021.

150. Yousif, NJ, Gosain, AK, Sanger, JR, et al. The nasolabial fold: A photogrammetric analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994; 93:70–77.

151. Yousif, NJ, Gosain, AK, Matloub, HS, et al. The nasolabial fold: An anatomic and histologic reappraisal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994; 93:60.

152. Yousif, NJ. Changes of the mid face with age. Clin Plast Surg. 1995; 22:213.

153. Zadoo, VP, Pessa, JE. Biological arches and changes to the curvilinear form of the aging maxilla. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 106:460–466.