34 Dentition and Common Oral Lesions

Dentition

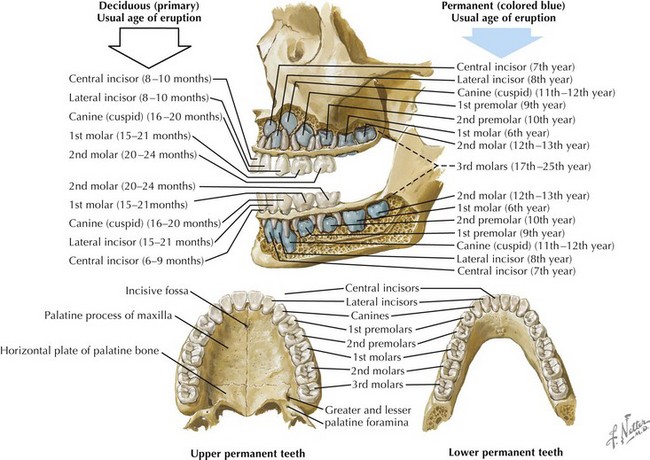

The development of the teeth begins in utero and continues well into adolescence. The 20 primary teeth (also known as deciduous or milk teeth) typically erupt between the ages of 6 months and 2 years. The exfoliation of the primary dentition and the eruption of the 32 permanent teeth usually begin at around age 6 years. On each side of the mouth, the mature permanent dentition consists of maxillary and mandibular central incisors, lateral incisors, canines, two premolars, and three molars (Figure 34-1).

Normal Tooth Anatomy

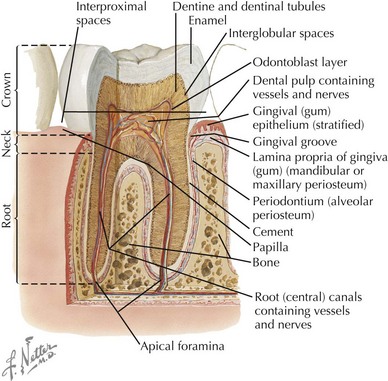

The visible portion of the tooth, which protrudes from the gingiva, is the crown, and its hard surface is an enamel made of hydroxyapatite crystals. The portion of the tooth that connects to the maxillary and mandibular alveolar bones is the root, and its hard covering is called cement. The neck of the tooth is the portion that connects the crown and the root. The periodontal ligament, or periodontal membrane, holds the root in place by attaching the cement to the periosteum of the alveolar bone. Beneath the protective overlying enamel and cement, a layer known as dentin provides the bulk of the body of the tooth. The innermost portion of the tooth, surrounded and protected by dentin, is the pulp chamber, which contains nerves, blood vessels, and connective tissue (Figure 34-2).

Dental Infections

Caries

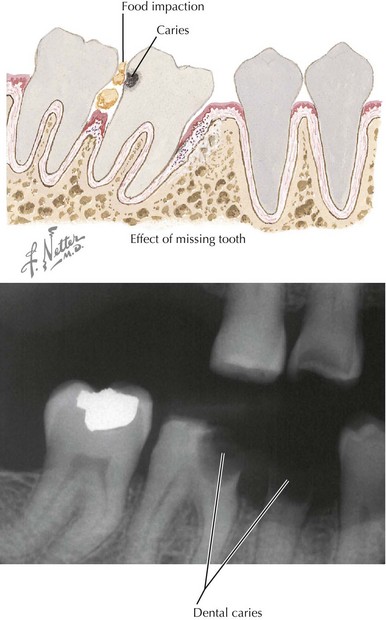

Bacteria, especially the Streptococcus mutans group, are typically transmitted from mother to infant soon after the eruption of the primary teeth. These bacteria colonize tooth surfaces and form plaques above and below the gingival margin. Caries result when these bacteria ferment sucrose from ingested dietary carbohydrate, producing organic acids on the tooth surface. These acids lead to the destruction of the hydroxyapatite crystals that give the enamel its structure, making the enamel more and more porous and eventually causing breakdown of the tooth surface (Figure 34-3). These areas of breakdown can erode through the enamel and dentin into the pulp, where an inflammatory response raises the pressure in the pulp chamber and can cause compression, and thus ischemia, of the pulp vessels. This is known as pulp necrosis.

Lesions of the Oral Soft Tissues

Anatomic Lesions of the Oral Cavity

Ankyloglossia

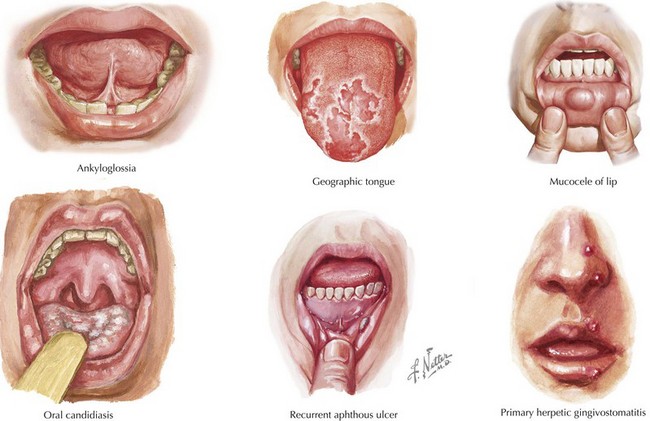

Uncommonly, children may be born with a short lingual frenulum, known as ankyloglossia or “tongue-tie” (Figure 34-4). Tongue movement may be restricted, and the close attachment of the frenulum to the tongue may cause the tip of the tongue to appear to have a mild cleft (“heart-shaped tongue”). The condition is more prevalent in boys than in girls. It does not usually affect speech or feeding, and the frenulum often lengthens as the child grows. In some cases, the short lingual attachment may impair a child’s ability to clear food from the buccal side of the teeth, which may promote bacterial growth and tooth decay. A frenulectomy may be required in the case of true disability.

Geographic Tongue

This benign condition is characterized by irregular red patches on the tongue, with yellow, gray, or white margins (see Figure 34-4). The filiform papillae are absent in these areas. The lesions typically spontaneously resolve and then subsequently appear elsewhere on the tongue, giving the condition its other name of “migratory glossitis.”

Common Soft Tissue Lesions of the Oral Cavity

Mucocele

This painless pseudocyst results from trauma to the duct of a minor salivary gland, usually in the lower lip or cheek (e.g., from lip biting). Ranging in size from 1 mm to several centimeters, it is usually smooth, soft, and bluish to translucent, filled with mucin from the damaged duct (see Figure 34-4). It may spontaneously drain as a result of the patient’s unroofing the lesion with his or her teeth; however, surgical excision may be required, in which case the entire underlying gland must be removed to prevent recurrence.

Aphthous Ulcers

These recurrent and painful ulcers, also known as canker sores, occur in up to one-third of children. Their cause is unclear, but viruses, T-cell dysfunction, trauma, and genetic predisposition have been implicated. They appear as white necrotic areas surrounded by a red margin, usually on the buccal and labial mucosa (see Figure 34-4). They usually resolve completely within 10 to 14 days. Differential diagnosis consideration should include recurrent traumatic ulcers from child abuse, oral manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease, secondary herpetic ulcers, neutropenic ulcers, and PFAPA (periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, cervical adenitis) syndrome.

Soft Tissue Infections of the Oral Cavity

Candidiasis

Thrush caused by the overgrowth of Candida spp. (mostly Candida albicans) occurs in 2% to 5% of normal newborns; it is also common in immunocompromised children and those who have used antibiotics or steroids. It presents as pseudomembranous white plaques on the buccal mucosa, palate, and tongue (see Figure 34-4). These plaques may be wiped away to reveal underlying raw, painful, erythematous mucosa. Treatment with an oral suspension of nystatin is usually effective; most clinicians recommend a course of 2 weeks or until 2 to 3 days after symptoms have resolved. For immunocompromised children or those who do not respond to nystatin, systemic fluconazole should be considered. Any objects that the infected child has regularly put in his or her mouth, such as pacifiers and toothbrushes, should be discarded.

Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis

Primary herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection presents with clusters of painful vesicles surrounded by erythema, which are primarily located on the gingiva, hard palate, and anterior tongue and extend to the vermilion border of the lips (see Figure 34-4). These vesicles may have a red halo, may ulcerate, and may become secondarily infected with bacteria. Other symptoms may include fever, lymphadenopathy, arthralgia, headache, and drooling or dehydration resulting from the pain associated with swallowing. Diagnosis is made by unroofing a vesicle with a sterile needle and sending vesicular fluid for viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, direct immunofluorescence, or Tzanck smear. Treatment with acyclovir within 3 days of symptom onset shortens the length of symptoms and the period of viral shedding. After primary HSV infection, recurrence may occur because the virus remains latent within the trigeminal ganglion until a flare is triggered by stress, sunlight, cold, trauma, or immunosuppression.

Cameron AC, Widmer RP. Handbook of Pediatric Dentistry, ed 3. Edinburgh: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

Feigin RD, Cherry JD. Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, ed 5. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004.

McTigue DJ. Diagnosis and management of dental injuries in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2000;47(5):1067-1084.

Norton NS. Netter’s Head and Neck Anatomy for Dentistry. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007.

Pinkham J, Casamassimo P, Fields HW, et al. Pediatric Dentistry: Infancy through Adolescence, ed 4. St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2005.

Zitelli BJ, Davis HW. Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis, ed 5. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.