Chapter 53 Dental Injuries

1 How frequently do health care practitioners encounter pediatric dental injuries?

Dale RA: Dentoalveolar trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am 18:521–538, 2000.

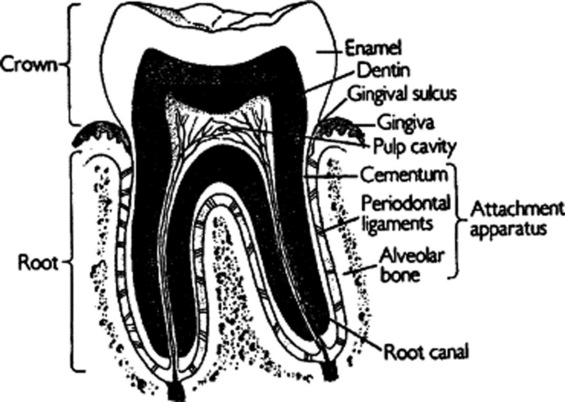

3 What are the other components of the tooth?

Other components of the crown of the tooth include dentin, a softer, microtubular structure, and pulp, which provides the tooth’s neurovascular supply (Fig. 53-1). The root of the tooth, which anchors it to the alveolar bone, consists of cementum, the periodontal ligament, and the alveolar bone.

4 Why is it important to distinguish primary from permanent teeth?

Management strategies for most dental injuries differ according to the type of tooth.

5 How do I make the distinction?

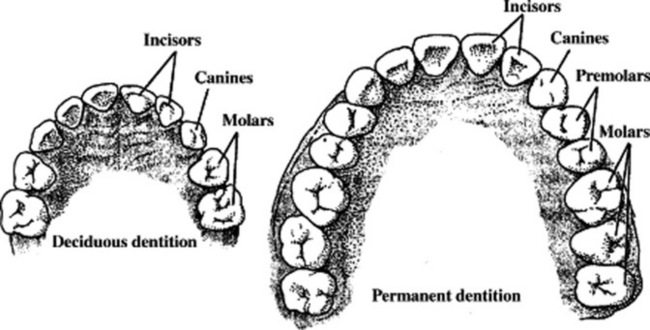

Primary (deciduous) teeth begin to erupt at about 6 months of age and are complete by 3 years. A full complement of primary teeth consists of 10 mandibular and 10 maxillary teeth, including four central incisors, four lateral incisors, four canines, and eight molars. Usually, mandibular teeth erupt before their maxillary counterparts (Fig. 53-2).

Primary (deciduous) teeth begin to erupt at about 6 months of age and are complete by 3 years. A full complement of primary teeth consists of 10 mandibular and 10 maxillary teeth, including four central incisors, four lateral incisors, four canines, and eight molars. Usually, mandibular teeth erupt before their maxillary counterparts (Fig. 53-2).

Permanent teeth typically begin to erupt at 5 years of age and are complete by 16 years of age. A full complement of permanent teeth consists of 16 mandibular teeth and 16 maxillary teeth, including four central incisors, four lateral incisors, four canines, eight bicuspids (premolars), and 12 molars (seeFig. 53-2).

Permanent teeth typically begin to erupt at 5 years of age and are complete by 16 years of age. A full complement of permanent teeth consists of 16 mandibular teeth and 16 maxillary teeth, including four central incisors, four lateral incisors, four canines, eight bicuspids (premolars), and 12 molars (seeFig. 53-2).

6 How do I accurately describe which tooth is injured?

The best and easiest way to describe an injured tooth is to divide the mouth into quadrants: right maxillary, right mandibular, left maxillary, and left mandibular. Then describe the type of tooth and the quadrant in which it is located. For example, the terms right maxillary central incisor and left mandibular canine denote both the type of tooth and the quadrant of the mouth in which it is found (seeFig. 53–2). Thus, you need not memorize the complex numbering or lettering systems.

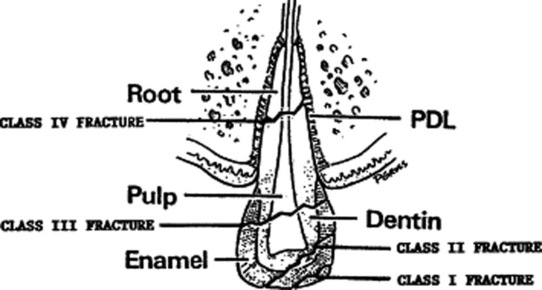

7 How are broken or fractured anterior teeth classified?

In the Ellis classification system, class I fractures involve only the enamel and result in jagged tooth edges but no other sequelae. Class II fractures break through both the enamel and dentin of the crown. The yellowish dentin is visible within the pearly white enamel. Class II fractures are often sensitive to heat, cold, and air. Class III fractures involve the pulp of the tooth. The pink and bleeding neurovascular bundle of the tooth is exposed, along with the dentin. Pain is often severe. Class IV fractures involve the root. The diagnosis must be confirmed by a dental radiograph or panoramic radiograph (Fig. 53-3).

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Clinical guideline on management of acute dental trauma. Chicago, American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, 2004, p 8. Available at www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?view_id=1&doc_id=6278

8 How are fractured teeth treated? How soon does a dentist need to be consulted?

Treatment depends on the classification of the tooth fracture:

Class I fractures require filing of sharp tooth edges to prevent oral soft tissue injury. Patients can see a dentist for tooth bonding if cosmetic issues arise.

Class I fractures require filing of sharp tooth edges to prevent oral soft tissue injury. Patients can see a dentist for tooth bonding if cosmetic issues arise.

Class II fractures require prompt treatment. The fractured tooth should be covered with dental foil (aluminum foil with an adhesive coating) or a calcium hydroxide coating made with commercially available products, such as Dycal. A base and accelerator are mixed and applied to the dry tooth. The patient is instructed to eat a soft diet, take analgesics for pain, and see a dentist within 48 hours. Correct treatment of class II fractures decreases the need for root canal therapy.

Class II fractures require prompt treatment. The fractured tooth should be covered with dental foil (aluminum foil with an adhesive coating) or a calcium hydroxide coating made with commercially available products, such as Dycal. A base and accelerator are mixed and applied to the dry tooth. The patient is instructed to eat a soft diet, take analgesics for pain, and see a dentist within 48 hours. Correct treatment of class II fractures decreases the need for root canal therapy.

Treatment of class III fractures is almost identical to that of class II fractures. Delay in dental treatment may result in severe pain and tooth abscess. Ultimately, the tooth requires total removal of pulpal tissue (root canal) with subsequent cosmetic tooth restoration.

Treatment of class III fractures is almost identical to that of class II fractures. Delay in dental treatment may result in severe pain and tooth abscess. Ultimately, the tooth requires total removal of pulpal tissue (root canal) with subsequent cosmetic tooth restoration.

Flores MT: Traumatic injuries in the primary dentition. Dent Traumatol 18:287–298, 2002.

10 When should I suspect an alveolar ridge fracture?

1 Tooth fractures most commonly occur in the anterior dentition and have 3 classes: Class I involves enamel only; class II involves enamel and dentin; and class III involves enamel, dentin, and pulp.

2 Class II and III fractures receiving proper treatment within 48 hours will have excellent outcomes.

3 Alveolar ridge fractures should be suspected when palpation of the gingiva reveals crepitus or step-offs, there are large gingival lacerations, or several teeth are luxated en bloc.

11 A 2-year-old patient struck his mouth on a coffee table. He reports pain with occlusion and chewing. Both maxillary central incisors are painful when percussed with a tongue blade, and the right one is slightly loose. What are the diagnosis and treatment?

Flores MT: Traumatic injuries in the primary dentition. Dental Traumatol 18:287–298, 2002.

12 What is a luxation injury? Define the five types

1 Intrusion describes a tooth impacted into the alveolar socket.

2 Extrusion describes a tooth that is vertically dislodged from the socket.

3 Lingual luxation is displacement of the tooth toward the tongue. It is common because of the frequency of injuries from an anterior force on the anterior teeth.

18 What is an avulsion injury?

An avulsion injury is complete displacement of the tooth (crown and root) from the alveolar socket.

20 What is the procedure for reimplanting an avulsed permanent tooth?

1 Hold the crown of the tooth, and rinse the root with Hank’s solution or saline. To avoid injury to the periodontal ligament, do not handle or scrub the root of the tooth.

2 Insert the root of the tooth into the alveolar socket. The concave part of the tooth should face the tongue.

3 The tooth should be splinted for 10–14 days.

4 If the tooth has been avulsed for a while and the alveolar socket is filled with blood, it may be necessary to perform a local nerve block and irrigate the socket with saline prior to successful tooth reimplantation.

5 Soft diet, analgesics, and antibiotics (penicillin or amoxicillin) are then prescribed.

22 Why should an avulsed primary tooth never be reimplanted?

www.iadt-dentaltrauma.org/Trauma/web

1 Avulsed primary teeth should never be reimplanted because of the risk of ankylosis and resultant facial deformities.

2 Fluids suitable to store avulsed permanent teeth in descending order are milk, saliva, and saline.

3 An avulsed permanent tooth that is reimplanted within 30 minutes has a 90% survival rate.

4 The prognosis for avulsed permanent teeth is highly time-dependent, and reimplantation should be completed as soon as possible.

25 Summarize the appropriate timing of dental consultation for patients with dental trauma

Luxation injuries with malocclusion or significant tooth mobility

Luxation injuries with malocclusion or significant tooth mobility

Urgent Dental Consultation (within 48 hours)

Nonurgent Dental Consultation (within 1 week)

KEY POINTS: PEDIATRIC DENTAL TRAUMA

1 Each patient with dental trauma should foremost be considered a trauma patient like any other.

2 A unique consideration in the evaluation of children with dental injuries is the need to understand normal dental development as proper identification of primary versus permanent dentition may affect diagnosis and treatment.

3 Primary teeth may be distinguished from permanent teeth because they are usually found in children younger than 6 years of age, are smaller in size, and have a smooth, not ridged, occlusive surface.

4 It is possible to prevent many sports-related dental injuries with the use of properly fitted mouthguards.