Dental caries and the assessment of restorations

Classification of caries

• Primary caries – caries developing on unrestored surfaces

• Secondary or recurrent caries – caries developing adjacent to restorations

• Residual caries – demineralized tissue left behind before filling the tooth.

Lesions of caries are also classified and/or described by the activity of the caries process. Terminology used includes:

Levels of disease

• D1 – Clinically detectable enamel lesions with intact surfaces

• D2 – Clinically detectable cavities limited to enamel

These distinctions are important with regard to management. Lesions at levels D1 and D2 are generally managed using preventative measures, whereas lesions at the D3 or D4 level are likely to require restorative treatment. Detection of lesions of caries and being able to assess the level of disease are therefore crucial in determining clinical treatment.

Diagnosis and detection of caries

Radiographic detection of lesions of caries

Bitewing radiographic techniques, using both film packets and digital sensors (solid-state and phosphor plates) as the image receptor, were described in Chapter 10. For caries detection, film packets and phosphor plates are preferred as the imaging area of the equivalent-sized solid-state sensors is smaller. It has been reported that on average three fewer interproximal tooth surfaces are shown per image.

Approximal lesions of caries are detectable radiographically only when there has been 30–40% demineralization, so allowing the lesion to be differentiated from normal enamel and dentine. The importance of optimum viewing conditions for both film and digital images, as described in Chapter 19, cannot be overemphasized when looking for these early subtle changes. Magnification is of particular importance, as shown in Fig. 20.1.

Radiographic assessment of caries activity

In the UK, the 2013 Faculty of General Dental Practice (UK)’s booklet Selection Criteria for Dental Radiography recommends that the frequency of these follow-up radiographs be linked to the caries risk of the patient. There are three risk categories – high, moderate or low risk – for both children and adults. The Selection Criteria booklet contains a number of evidence-based recommendations, the main ones of which are summarised in Table 20.1. As can be seen for high risk children and adults 6-monthly time intervals are recommended, for moderate risk patients 12-monthly intervals and for low risk children 12–18 month intervals and for low risk adults 2-yearly intervals.

Table 20.1

| Recommendation | Evidence-based Grading* |

| All children designated as high caries risk should have six-monthly posterior bitewings taken until no new or active lesions are apparent and the individual has entered another risk category (Bitewings should not be taken more frequently and it is imperative to reassess caries risk in order to justify using this interval again.) | B |

| All children designated as moderate caries risk should have annual posterior bitewings taken until no new or active lesions are apparent and the individual has entered another risk category. | B |

| All children designated as low caries risk should have posterior bitewings taken at approximately 12–18 month intervals in the primary dentition and at approximately two-yearly intervals in the permanent dentition. More extended radiographic recall intervals may be employed if there is explicit evidence of continuing low caries risk. | B |

| All adults designated as high caries risk should have six-monthly posterior bitewings taken until no new or active lesions are apparent and the individual has entered another risk category (Bitewings should not be taken more frequently and it is imperative to reassess caries risk in order to justify using this interval again. It is also important to remember that rates of caries progress in enamel and dentine will differ and that rates in adults may well be slower than in children) | C |

| All adults designated as moderate caries risk should have annual posterior bitewings taken until no new or active lesions are apparent and the individual has entered another risk category | C |

| All adults designated as low caries risk should have posterior bitewings taken at approximately two-yearly intervals. More extended radiographic recall intervals may be employed if there is explicit evidence of continuing low caries risk. | C |

| The taking of ‘routine’ radiographs based solely on time elapsed since the last examinations is not supportable. | C |

| Intervals between subsequent radiographic examinations must be reassessed for each new period as patients can move in and out of caries risk categories over time. | C |

| CBCT should not be used as a routine method of caries diagnosis | B |

*Evidence-based grading B = based on evidence from well conducted clinical studies but with no specific in vitro validation studies; C = based on evidence from expert committee reports or opinions and/or clinical experience of respected authorities and indicates an absence of directly applicable studies of good quality.

Radiographs used to monitor the progression of caries lesions need to be geometrically identical – hence the need for image receptor holders and beam-aiming devices (see Ch. 10). They should also be similarly exposed to give comparable contrast and density.

Geometrically reproducible digital images can be superimposed and the information in one image subtracted from the other to create the subtraction image which shows the changes that have taken place between the two investigations (see Ch. 5).

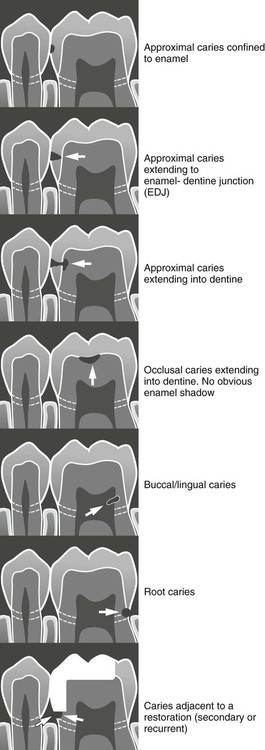

Radiographic appearance of caries lesions

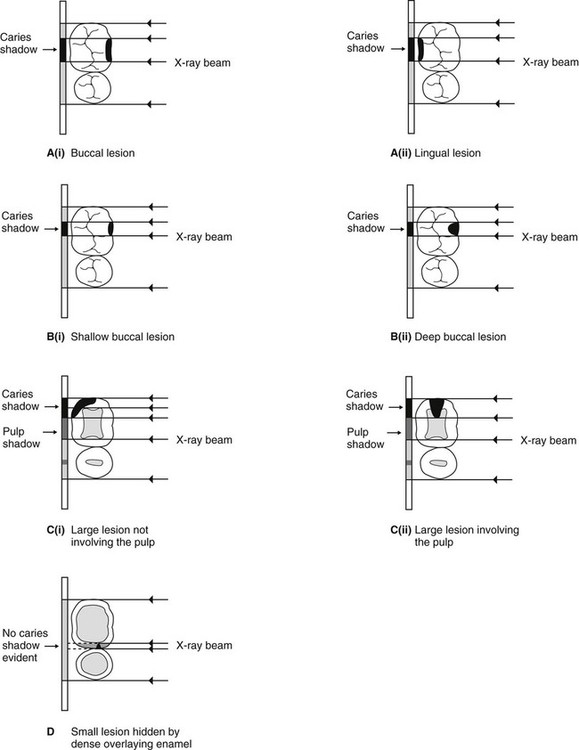

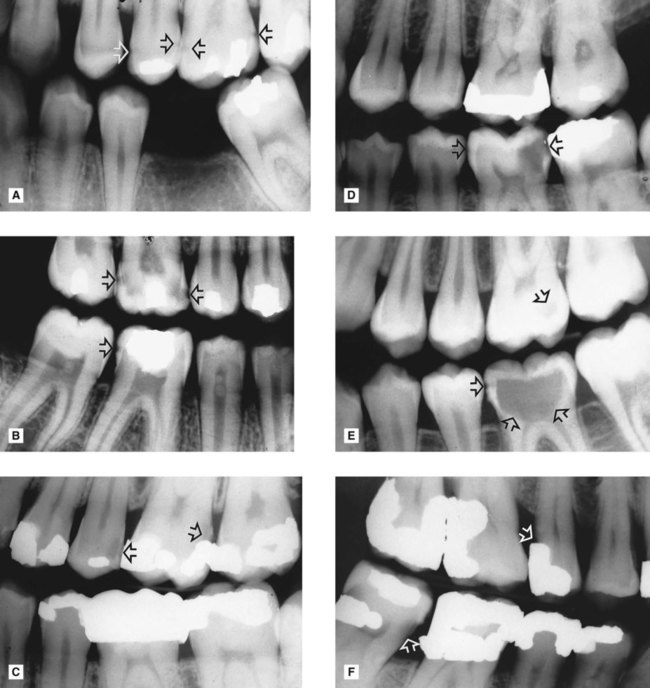

As lesions of caries progress and enlarge, they appear as differently shaped areas of radiolucency in the crowns or necks of the teeth. These shapes are fairly characteristic and vary according to the site and size of the lesion. They are illustrated diagrammatically in Fig. 20.2 and examples are shown in Fig. 20.3.

Other important radiographic appearances

Radiographic detection of caries lesions is not always straightforward. It can be complicated by:

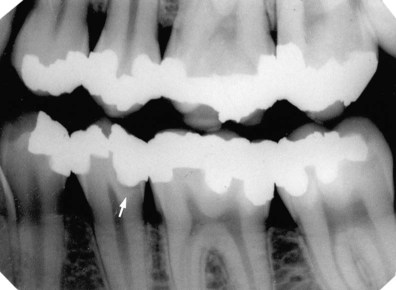

Residual caries

The rationale for removal of caries has changed in recent years. The primary aim nowadays when excavating dentine caries is to remove only the highly infected, irreversibly demineralized dentine in order to allow effective restoration of the cavity and surface anatomy of the tooth and to prevent disease progression. In other words, demineralized tissue (residual caries) is left behind in the base of the cavity and the tooth restored. Radiographically, this inactive caries may show a zone of radiolucency beneath the restoration. This appearance is identical to that of an active caries lesion under a restoration (see Fig. 20.4).

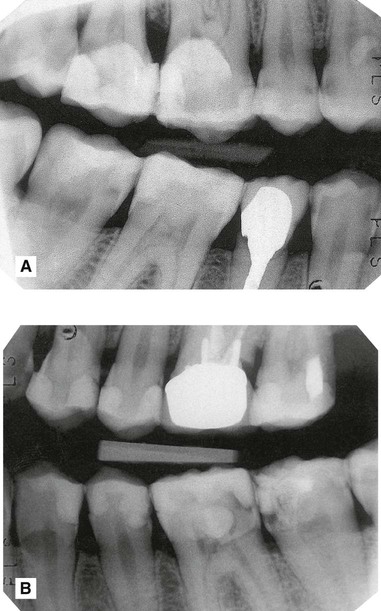

Radiodensity of adhesive restorations

The development of successful adhesive restorative materials in recent years, including dentine-bonding agents and glass ionomer cements, has resulted in many teeth being restored with non-metallic fillings. These various adhesive materials vary considerably in their radiodensity and do not appear as white on radiographic images as traditional amalgam, as shown in Fig. 20.5. Identifying subtle radiolucent lesions of caries adjacent to these materials can be very difficult, if not impossible.

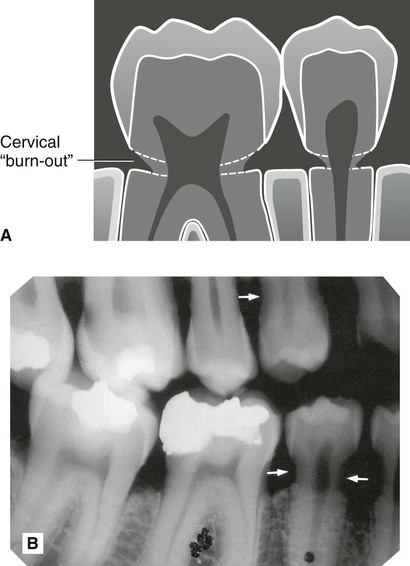

Cervical burn-out or cervical translucency

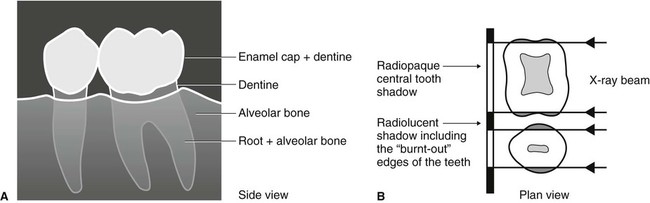

This radiolucent shadow is often evident at the neck of the teeth, as illustrated in Fig. 20.6. It is an artefactual phenomenon created by the anatomy of the teeth and the variable penetration of the X-ray beam.

• In the crown – the dense enamel cap and dentine

• In the root – dentine and the buccal and lingual plates of alveolar bone (see Fig. 20.7).

Thus, at the edges of the teeth in the cervical region, there is less tissue for the X-ray beam to pass through. Less attenuation therefore takes place and virtually no opaque shadow is cast of this area on the radiograph. It therefore appears radiolucent, as if some cervical tooth tissue does not exist or that it has been apparently burnt-out.

• It is located at the neck of the teeth, demarcated above by the enamel cap or restoration and below by the alveolar bone level

• It is triangular in shape, gradually becoming less apparent towards the centre of the tooth

• Usually all the teeth on the radiograph are affected, especially the smaller premolars.

In contrast, root and recurrent caries lesions, although they also often affect the cervical region, have no apparent upper and lower demarcating borders. These lesions are saucer-shaped and tend to be localized, as shown in Fig. 20.2. If in doubt, the diagnosis should be confirmed clinically by direct vision and gentle probing having cleaned and dried the area.

Important points to note

• Burn-out is more obvious when the exposure factors are increased, as required ideally for detecting approximal caries.

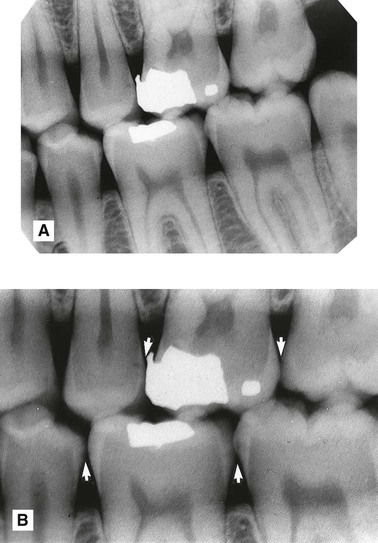

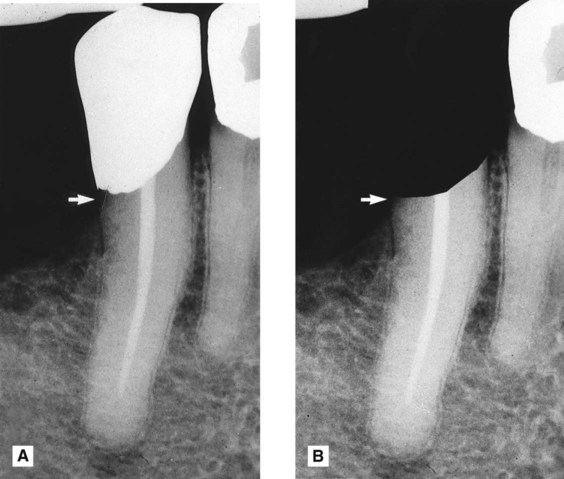

• It is also more apparent, by the perceptual problem of contrast, if the tooth contains a metallic restoration, which may make the zone above the cervical shadow completely radiopaque (see Fig. 20.8 and Ch. 1, Fig. 1.16). As this area is also the main site for recurrent caries, diagnosis is further complicated.

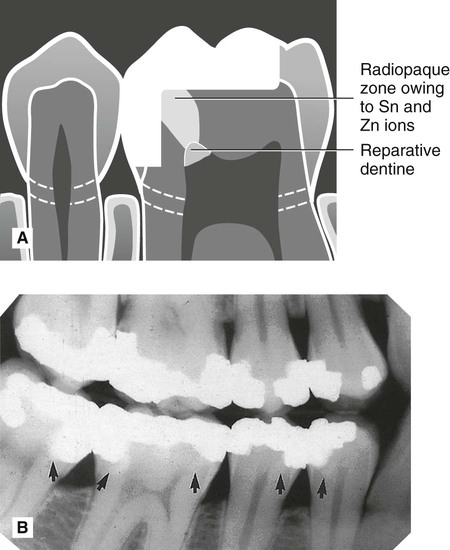

Dentinal changes beneath amalgam restorations

Following attack by caries, posterior teeth are still commonly restored using dental amalgam. An amalgam is defined as an alloy of mercury with another metal or metals. In dental amalgam, mercury is mixed with an alloy powder. The alloy powders available principally contain silver, tin and copper with small amounts of zinc. It has been shown that, with time, tin and zinc ions are released into the underlying demineralized (but not necessarily infected) dentine producing a radiopaque zone within the dentine which follows the S-shape curve of the underlying tubules (see Fig. 20.9). The radiopacity of this zone may make the normal dentine on either side appear more radiolucent by contrast. This somewhat more radiolucent normal dentine may simulate the radiolucent shadows of caries and lead to difficulties in diagnosis.

Limitations of radiographic detection of caries

• Lesions of caries are usually larger clinically than they appear radiographically and very early lesions are not evident at all.

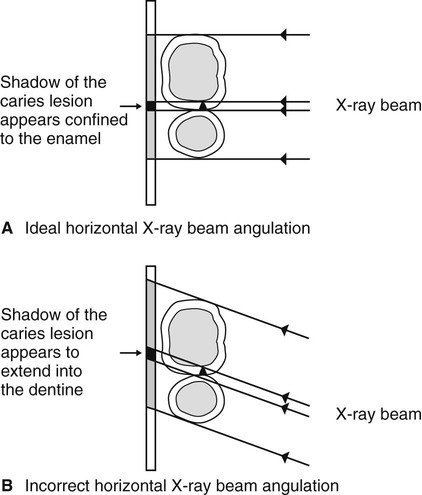

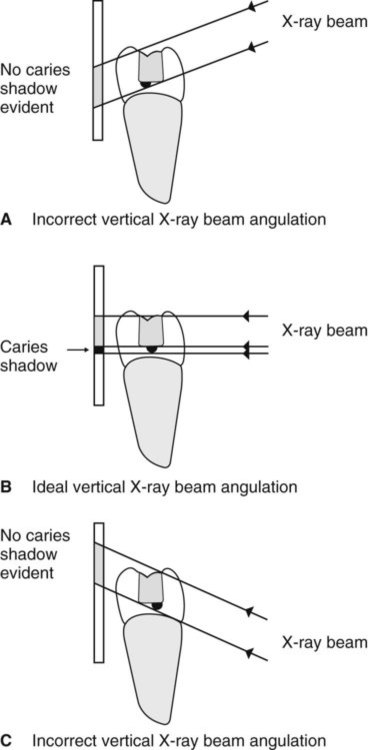

• Technique variations in image-receptor and X-ray beam positions can affect considerably the image of the caries lesion – varying the horizontal tubehead angulation can make a lesion confined to enamel appear to have progressed into dentine (see Fig. 20.10) – hence the need for accurate, reproducible techniques as described in Chapter 10.

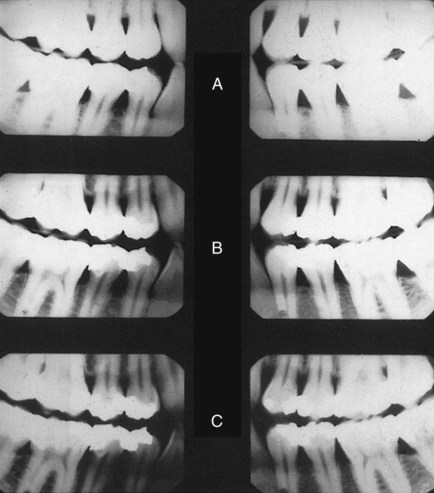

• Exposure factors can have a marked effect on the overall radiographic contrast (see Fig. 20.11) on film-captured images and thus affect the appearance or size of caries lesions on the film.

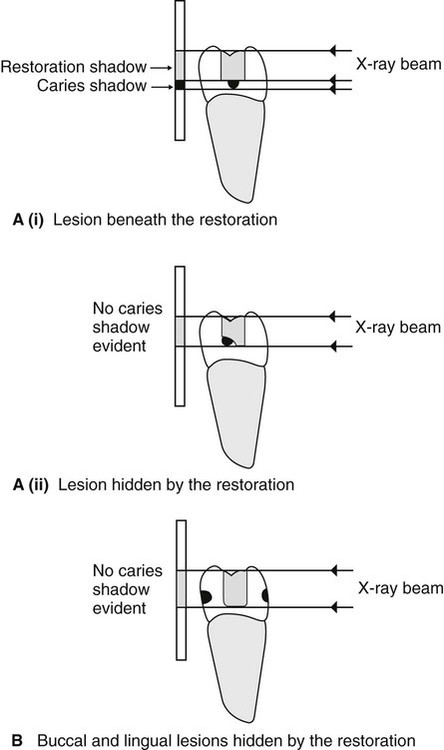

• Superimposition and a two-dimensional image (digital or film) mean that the following features cannot always be determined:

– The exact site of a caries lesion, e.g. buccal or lingual

– The buccolingual extent of a lesion

– The distance between the caries lesion and the pulp horns. These two shadows can appear to be close together or even in contact but they may not be in the same plane

– The presence of an enamel lesion – the density of the overlying enamel may obscure the zone of decalcification

– The presence of caries adjacent to restorations may be completely obscured by the restoration (see Fig. 20.12).

Radiographic assessment of restorations

Critical assessment of the restoration

The important features to note include:

• The type and radiodensity of the restorative material, e.g.

• Adaptation of the restorative material to the base of the cavity

• Marginal fit of cast restorations

Assessment of the underlying tooth

The important features to note include:

• Caries adjacent to restorations

• Residual caries (see earlier and Fig. 20.4)

• Radiopaque shadow of released tin and zinc ions (see earlier and Fig. 20.9)

Examples showing several of these features are shown in Fig. 20.13.

Limitations of the radiographic image

• Technique variations in X-ray tubehead position may cause recurrent caries lesions to be obscured (see Fig. 20.14)

• Cervical burn-out shadows tend to be more obvious when their upper borders are demarcated by dense white restorations because of the increased contrast differences (see Fig. 20.8)

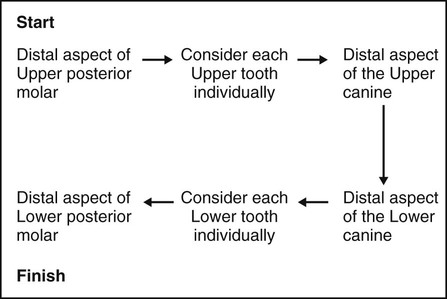

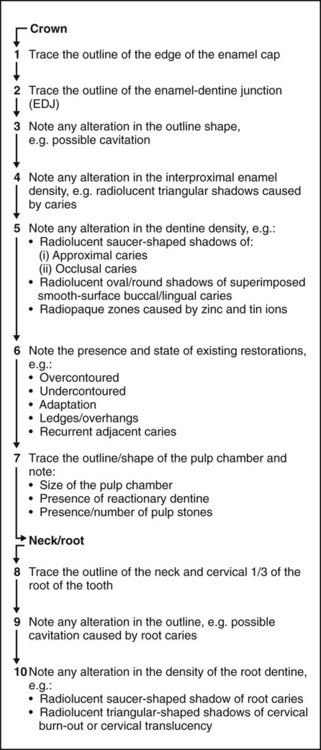

Suggested guidelines for interpreting bitewing images

Overall critical assessment

A typical series of questions that should be asked about the quality of a bitewing image based on the ideal quality criteria described in Chapter 10, include:

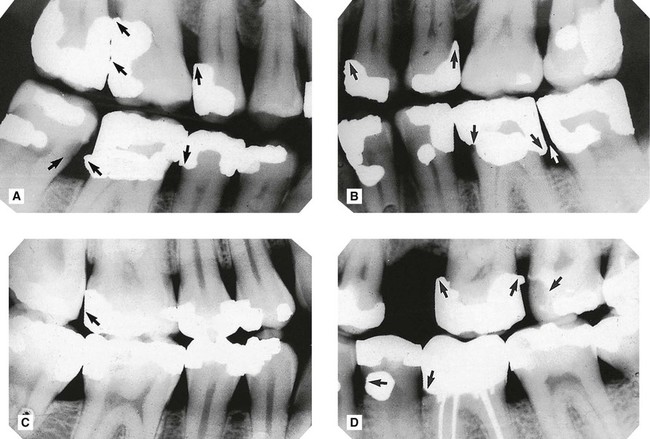

. B Large approximal lesions with extensive dentine involvement

. B Large approximal lesions with extensive dentine involvement  and a small lesion

and a small lesion  . C Approximal lesion extending into dentine

. C Approximal lesion extending into dentine  and recurrent caries

and recurrent caries  . D Small and extensive approximal lesions

. D Small and extensive approximal lesions  . E Small occlusal lesion

. E Small occlusal lesion  and extensive occlusal lesion

and extensive occlusal lesion  , apart from the small approximal enamel lesion, the enamel cap appears intact. F Root caries

, apart from the small approximal enamel lesion, the enamel cap appears intact. F Root caries  and recurrent caries

and recurrent caries  .

.

(arrowed). It is impossible to assess whether the lesion is active or inactive.

(arrowed). It is impossible to assess whether the lesion is active or inactive.

.

.

from the side showing the three-dimensional structures involved in the formation of the radiographic image. Note that in the cervical region there is less tissue present. B Plan view at the level of the necks of the teeth. Through the centre of the teeth there is a large mass of dentine to absorb the X-ray beam, while at the edges there is only a small amount. The edges of the necks of the teeth are therefore not dense enough to stop the X-ray beam, so their normally opaque shadows do not appear on the final radiograph.

from the side showing the three-dimensional structures involved in the formation of the radiographic image. Note that in the cervical region there is less tissue present. B Plan view at the level of the necks of the teeth. Through the centre of the teeth there is a large mass of dentine to absorb the X-ray beam, while at the edges there is only a small amount. The edges of the necks of the teeth are therefore not dense enough to stop the X-ray beam, so their normally opaque shadows do not appear on the final radiograph.

. B The same image but with the white restoration blacked out. The zone beneath the restoration (arrowed) now appears less radiolucent.

. B The same image but with the white restoration blacked out. The zone beneath the restoration (arrowed) now appears less radiolucent.