Chapter 261 Dengue Fever and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever

Etiology

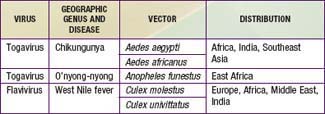

There are at least 4 distinct antigenic types of dengue virus, which is a member of the family Flaviviridae. In addition, 3 other arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) cause similar or identical febrile diseases with rash (Table 261-1).

Epidemiology

Dengue-Like Diseases

Dengue-like diseases may also occur in epidemics. Epidemiologic features depend on the vectors and their geographic distribution (see Table 261-1). Chikungunya virus is widespread in the most populous areas of the world. In Asia, A. aegypti is the principal vector; in Africa, other Stegomyia species may be important vectors. In Southeast Asia, dengue and chikungunya outbreaks occur concurrently. Outbreaks of o’nyong-nyong and West Nile fever usually involve villages or small towns, in contrast to the urban outbreaks of dengue and chikungunya.

Differential Diagnosis

Because meningococcemia, yellow fever (Chapter 262), other viral hemorrhagic fevers (Chapter 263), many rickettsial diseases, and other severe illnesses caused by a variety of agents may produce a clinical picture similar to dengue hemorrhagic fever, the etiologic diagnosis should be made only when epidemiologic or serologic evidence suggests the possibility of a dengue infection.

Treatment

Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever and Dengue Shock Syndrome

Sedation may be required for children who are markedly agitated. Use of vasopressors has not resulted in a significant reduction of mortality over that observed with simple supportive therapy. Disseminated intravascular coagulation may require treatment (Chapter 477). Corticosteroids do not shorten the duration of disease or improve prognosis in children receiving careful supportive therapy.

Bethell DB, Gamble J, Pham PL, et al. Noninvasive measurement of microvascular leakage in patients with dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:243-253.

Blaney JEJr, Matro JM, Murphy BR, et al. Recombinant, live-attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine formulations induce a balanced, broad and protective neutralizing antibody response against each of the four serotypes in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 2005;79:5516-5528.

Capeding RZ, Brion JD, Caponpon MM, et al. The incidence, characteristics, and presentation of dengue virus infections during infancy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:330-336.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health advisory—increased potential for dengue infection in travelers returning from international and selected domestic areas. Health Alert Network. July 25, 2010. CDCHAN-00315-2010-07-25-ADV-N

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Locally acquired dengue—Key West, Florida, 2009–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:577-581.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Travel associated dengue surveillance—United States, 2006–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:715-720.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dengue fever among US travelers returning from the Dominican Republic—Minnesota and Iowa, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:654-656.

Chau TN, Quyen NT, Thuy TT, et al. Dengue in Vietnamese infants—results of infection-enhancement assays correlate with age-related disease epidemiology and cellular immune responses correlate with disease severity. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:518-524.

Dung NM, Day NP, Tam DT, et al. Fluid replacement in dengue shock syndrome: A randomized, double-blind comparison of four intravenous-fluid regimens. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:787-794.

Feldmann H, Geisbert TW. Ebola haemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 2011;377:849-860.

Guirakhoo F, Pugachev K, Zhang Z, et al. Safety and efficacy of chimeric yellow fever—Dengue virus tetravalent vaccine formulations in nonhuman primates. J Virol. 2004;78:461-475.

Guzman MG, Kouri G. Dengue haemorrhagic fever integral hypothesis: confirming observations, 1987–2007. Trans R Soc Trop Med. 2008;102:522-523.

Halstead SB. Seminar: Dengue. The Lancet. 2007;370:1644-1652.

Kliks SC, Nisalak A, Brandt WE, et al. Evidence that maternal dengue antibodies are important in the development of dengue hemorrhagic fever in infants. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38:411-419.

Monath TP, McCarthy K, Bedford P, et al. Clinical proof of principle for ChimeriVax: recombinant live, attenuated vaccines against flavivirus infections. Vaccine. 2002;20:1004-1018.

Růžek D, Yakimenko VV, Karan L, et al. Omsk haemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 2010;376:2104-2112.

Simasthien S, Thomas SJ, Watanaveeradej V, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a tetravalent live-attenuated dengue vaccine in flavivirus naïve children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:426-433.

Teixeria MG, Barreto ML. Diagnosis and management of dengue. BMJ. 2009;339:1189-1193.

Ubol S, Masrinoul P, Chaijaruwanich J, et al. Differences in global gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells indicate a significant role of the innate responses in progression of dengue fever but not dengue hemorrhagic fever. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1459-1467.

Vaughn DW, Green S, Kalayanarooj S, et al. Dengue viremia titer, antibody response pattern and virus serotype correlate with disease severity. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:2-9.

Wilder-Smith A, Schwartz E. Dengue in travelers. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:924-933.

Wills BA, Dung NM, Loon HT, et al. Comparison of three fluid solutions for resuscitation in dengue shock syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:877-889.