149 Dengue

Millions of individuals across the tropical and subtropical world become infected with dengue viruses every year. A small percentage of individuals infected with dengue develop overt clinical illness, and an even smaller percentage develops severe dengue. With the enormous shift to urban living, increase in tourism, business-related travel, and global deployment of military and international nongovernmental organizations in recent decades, dengue cases have been seen more frequently outside endemic areas. The daytime biting habits of the Aedes mosquito and the urban environment visited by most international travelers make it all but impossible to avoid exposure (bed nets offer only limited protection). There is no vaccine or prophylaxis available. Dengue infections in travelers are monitored by TropNetEurop (www.tropneteurope/dengue) and in the United States by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; www.cdc.gov/dengue). Most infections in travelers (78%) manifest after short holidays or business-related travel to South and Southeast Asia and the Americas.1,2 There have been major epidemics in West Africa in recent years.2

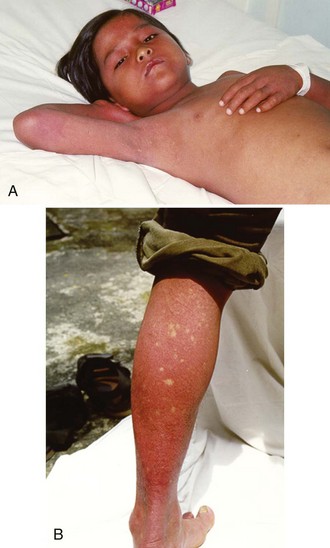

Of the many clinical features associated with dengue infections, from the standpoint of threat to life and clinical intervention, the most important is increased vascular permeability leading to dengue shock syndrome (DSS). Children are particularly prone to the development of shock, probably because of age-related differences in capillary fragility that may make them more susceptible than adults to capillary leak syndrome.3

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

Dengue is the most widely distributed mosquito-borne viral infection of humans, affecting an estimated 100 million people worldwide each year, with 40% (2.5 billion) of the world’s population estimated to be at risk of infection.4 It is endemic in parts of Asia and the Americas and has been reported increasingly from many tropical countries in recent years.4,5 It is now classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) into dengue fever and severe dengue (Box 149-1). The most important feature of severe dengue is increased capillary permeability, leading to DSS (Figure 149-1). It is among the leading causes of hospitalization in Asia during the rainy season, with 500,000 cases reported annually to the WHO. When shock becomes established, mortality rates of 12% to 40% have been reported, although this can be less than 1% when patients are looked after by experienced clinical teams.

Box 149-1

World Health Organization Case Classification 2009

The dengue virus is a single-stranded, positive sense RNA virus of approximately 11 kb in length and encodes 3 structural and 7 nonstructural genes.6 It is a member of the Flavivirus genus, which also includes yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, West Nile virus, and hepatitis C virus.7 There is considerable genetic diversity in the dengue virus family, with four serotypes (Den-I, Den-II, Den-III, and Den-IV), all of which may produce a nonspecific febrile illness, dengue fever, or may result in the more severe manifestation of severe dengue.

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

Severe dengue is characterized by increased vascular permeability and plasma leakage, thrombocytopenia, and hemorrhage (see Figure 149-1). Vascular permeability is the most important parameter determining the severity of dengue, and the plasma leak that occurs can precipitate DSS through circulatory failure (reduced pulse pressure and hypotension).5 The capillary leak predisposes to pulmonary edema, pleural effusion, ascites, intravascular compromise, and hemoconcentration. Dengue is characterized by only mild hemorrhage, as indicated by spontaneous petechiae and a positive tourniquet test, whereas in severe dengue, mucosal bleeding (including that associated with peptic ulceration and menorrhagia) and other clinically important manifestations of hemorrhage can be present. These are usually associated with prolonged shock.

The most widely cited hypothesis to explain the vascular leak and hemorrhage associated with dengue is increased viral replication due to enhanced infection of monocytes in the presence of preexisting antidengue antibodies at subneutralizing levels, leading to antibody-dependent immune enhancement.8 This observation, which has strong epidemiologic and in vitro experimental evidence to support it, argues that in asymptomatic dengue infection, the moderate viremia is controlled. The host immune system develops long-lasting immunity to the serotype of the infecting strain and short-lived cross-protection against heterologous serotypes. After a few months, the levels of cross-protective antibodies directed against the heterologous serotypes fall below neutralizing levels, however, and from this stage onward infection with a second heterologous strain may result in increased viral uptake via Fcγ receptors into monocytes and enhanced viral replication. Severe disease has been reported during primary infections, however, and not all secondary infections lead to severe disease, so other theories (viral and host genetic factors) have been suggested to explain the complex epidemiologic and immunopathogenetic features.9–12

Clinical Features

Clinical Features

Dengue fever is a mild, self-limited febrile episode that is commonly associated with a rash. It usually begins with fever, respiratory symptoms (sore throat, coryza, cough), anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and headache. Back pain, myalgias, arthralgias, and conjunctivitis also may occur. The initial fever usually resolves within 1 week, and a few days later a generalized morbilliform or maculopapular rash may develop. Fever may return with the rash. As noted, dengue is now classified into dengue and severe dengue by the WHO (see Box 149-1). These two groups form part of a continuous spectrum of severity, with the most important clinical features of severe dengue being capillary permeability leading to DSS (see Figure 149-1). Other complications include severe mucosal (and less commonly, intracerebral and pulmonary hemorrhage) bleeding, pleural effusions, encephalopathy, pneumonia, and liver dysfunction. The differential diagnosis is extensive and varies depending on where the patient is seen, but would include malaria, typhoid, leptospirosis, scrub and murine typhus, septicemia, other viral hemorrhagic fevers (e.g., Ebola, Lassa fever), chikungunya, West Nile fever, o’nyong-nyong fever, and Rift Valley fever (usually without a rash).

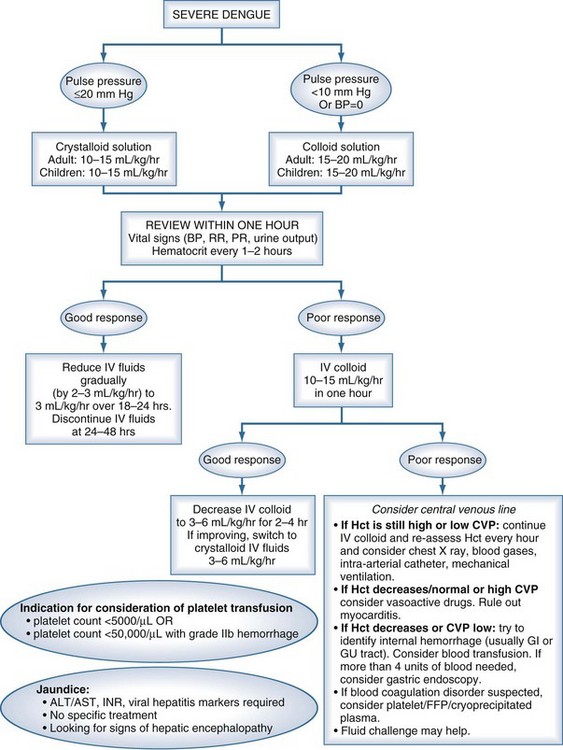

A pulse pressure of less than 20 mm Hg is one of the earliest manifestations of shock and usually occurs before the onset of systolic hypotension. The mainstay of treatment is prompt but careful fluid resuscitation. If appropriate volume resuscitation is instituted at an early stage, shock is usually reversible; in certain severe cases and in patients who are inappropriately resuscitated, patients may progress to irreversible shock and death. Careful clinical judgment is required throughout the patient’s stay in the hospital to maintain an effective circulation while assiduously avoiding fluid overload. During the critical phase of illness, regular review (every 15-30 minutes) of vital signs—pulse rate, blood pressure (BP), respiratory rate (RR), and peripheral temperature—as well as measurement of hematocrit (Hct) at least every 2 hours (more frequently if very severe or unstable).13,14,15 It is imperative that these measurements be made, the patients assessed, and the treatment modified in light of the clinical situation and results. Ideally the Hct should be measured on the ward (or the results be made available immediately). Dengue has a very dynamic clinical progression, and it is not acceptable to define therapy on the basis of blood results taken hours earlier. For patients with DSS, the WHO recommends immediate volume replacement with isotonic crystalloid solutions, followed by the use of plasma or colloid solutions, specifically dextrans, for profound or continuing shock.4

Thrombocytopenia is a very common feature in dengue, and platelet function is abnormal. Mild prolongation of the prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times with reduced fibrinogen levels is common, but fibrin degradation products have not been found to be elevated to a degree consistent with classic disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Patients with DSS have significant abnormalities in all the major pathways of the coagulation cascade.16

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

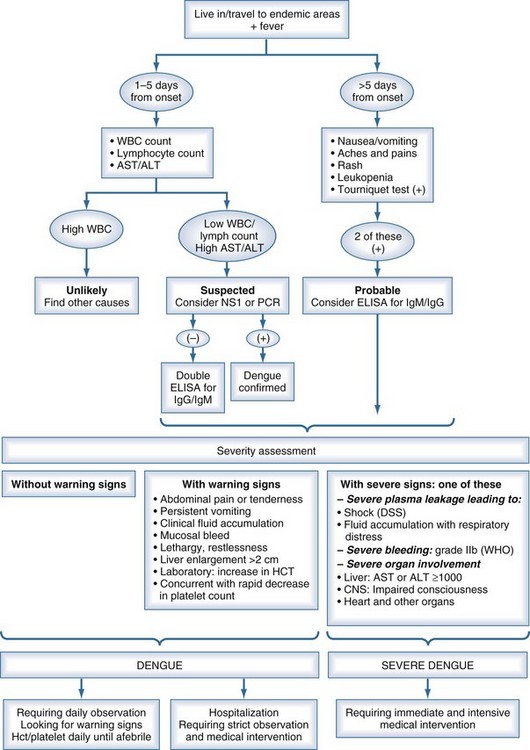

Classic dengue illness can be an easy diagnosis to make in endemic regions with experienced clinical staff and a high prior probability that a febrile illness with rash and thrombocytopenia is caused by dengue. Most of the symptoms and signs accompanying dengue infection are common to many febrile illnesses, with few features that reliably discriminate dengue, especially at early stages.17,18 The differential diagnosis invariably is large; it is region, country, and season specific. The differential diagnosis includes measles, rubella, enterovirus, influenza, typhoid, chikungunya, scarlet fever, malaria, leptospirosis, hepatitis A, rickettsiosis, bacterial sepsis, Hanta virus infection, viral hemorrhagic fevers (including Ebola, Lassa fever), West Nile virus, o’nyong-nyong fever, and Rift Valley fever (usually without a rash). Because of the variation in clinical findings and the multiplicity of possible causative agents, the descriptive term dengue-like disease may be used until the clinical picture becomes clearer or the laboratory provides a specific diagnosis (Figure 149-2).

Proof of a dengue infection depends on confirmatory RT-PCR, dengue serology, specific dengue NS1 antigen detection, or viral isolation if available. Serologic confirmation of acute dengue infection relies on the demonstration of specific immunoglobulin (Ig)M and IgG antibodies against dengue in the serum of patients. Dengue virus RNA also can be amplified by reverse transcriptase nested polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from serum.19 Viral isolation is performed by culturing the patient’s serum with Aedes albopictus C6/36 cell monolayers. Virus infection of C6/36 cells is confirmed by immunofluorescent assay using a flavivirus-specific monoclonal antibody.

Management

Management

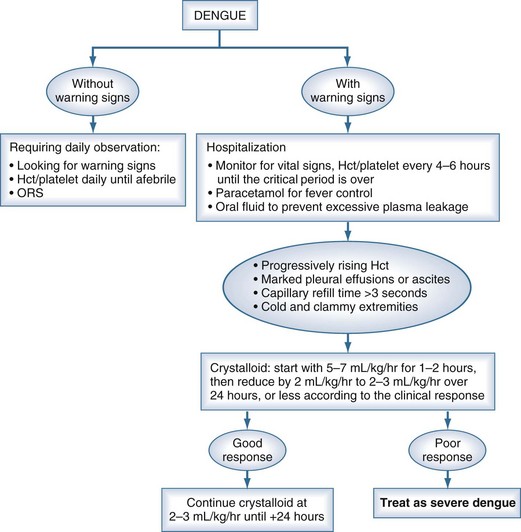

Although there are currently no specific drugs for dengue, effective treatment is based primarily on judicious fluid management (Figure 149-3). Prompt restoration of circulating plasma volume is the cornerstone of therapy for patients with DSS. For uncomplicated dengue fever, less aggressive oral or parenteral fluid therapy frequently is indicated. This section focuses on the management of DSS; the management of unusual complications such as dengue encephalopathy or fulminant hepatitis is not addressed, as the management of these complications is similar to standard treatment protocols.

Severe Dengue Including Dengue Shock Syndrome

For most patients with DSS, resuscitation should be started with an isotonic crystalloid solution (physiologic saline, Ringer’s lactate, or Ringer’s acetate) at a rate of 15 to 20 mL/kg over 1 hour. If the patient’s clinical condition has stabilized after this time (wider pulse pressure, stable pulse rate, warm peripheries, stable Hct), the rate of fluid administration may be reduced to 10 mL/kg/h for 2 hours, then gradually reduced to maintenance levels over the next 6 to 8 hours. A suitable schedule might be as follows: 10 mL/kg/h for 2 hours, 7.5 mL/kg/h for 2 hours, 5 mL/kg/h for 4 hours, then 2 to 3 mL/kg/h for 24 to 36 hours. For most patients, IV therapy can be stopped at this time, provided that the clinical condition has been stable for 24 hours.4

Blood Transfusion

Blood transfusion is indicated only for patients with major bleeding and should be undertaken with extreme care because of the problem of fluid overload. In patients with DSS, major bleeding is almost always associated with severe or prolonged shock and is usually from the gastrointestinal tract or vagina. Severe mucosal bleeding appears to be more common in adult patients. Underlying causes include profound thrombocytopenia in combination with gastritis or stress ulceration. Internal bleeding may not become apparent for many hours until the first melena stool is passed. Blood transfusion should be considered in all patients who fail to improve clinically after appropriate fluid resuscitation, particularly if the Hct is stable or unexpectedly falling. (<35% Hematocrit and persistent shock). Platelet concentrates and fresh frozen plasma also can be helpful but are effective only for a few hours, and routine platelet transfusions are not indicated.20

Steroids are not recommended in the management of severe dengue; the evidence for this comes from a series of small trials performed in the 1970s and 1980s. The total number of patients with severe dengue randomized to steroids (each study used a different form of steroid in varying doses, and not all studies were controlled) in the international literature is 150 in 5 published studies.21–25 Most of these reported no benefit in the small number of patients investigated, although one trial reported a remarkable reduction in mortality.21 The evidence from these five studies would not now be considered sufficiently robust on which to base a global recommendation.

Key Points

Hales S, de Wet N, Maindonald J, Woodward A. Potential effect of population and climate changes on global distribution of dengue fever: an empirical model. Lancet. 2002;360:830-834.

Gubler DJ. Cities spawn epidemic dengue viruses. Nat Med. 2004;10:129-130.

Halstead SB. Pathogenesis of dengue: challenges to molecular biology. Science. 1988;239:476-481.

Cummings DA, Iamsirithaworn S, Lessler JT, McDermott A, Prasanthong R, Nisalak A, et al. The impact of the demographic transition on dengue in Thailand: insights from a statistical analysis and mathematical modeling. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000139. Epub 2009 Sep 1

Wills BA, Nguyen MD, Ha TL, Dong TH, Tran TN, Le TT, et al. Comparison of three fluid solutions for resuscitation in dengue shock syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:877-889.

1 Jelinek T, Muhlberger N, Harms G, et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of imported dengue fever in Europe: Sentinel surveillance data from TropNetEurop. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:1047-1052.

2 Jelinek T. Trends in the epidemiology of dengue fever and their relevance for importation to Europe. Euro Surveill. 14(25), 2009 Jun 25. pii: 19250

3 Gamble J, et al. Age-related changes in microvascular permeability: A significant factor in the susceptibility of children to shock? Clin Sci (Lond). 2000;98:211-216.

4 Dengue; Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control. World Health Organization; 2009.

5 Hales S, de Wet N, Maindonald J, Woodward A. Potential effect of population and climate changes on global distribution of dengue fever: An empirical model. Lancet. 2002;360:830-834.

6 Chang G. Molecular biology of dengue viruses. In: Gubler D, Kuno G, editors. Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. Wallingford, Oxford: CAB International, 1997.

7 Westaway EG, Blok J. Taxonomy and evolutionary relationships of the Flavivirus. In: Gubler D, Kuno G, editors. Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. Wallingford, Oxford: CAB International, 1997.

8 Halstead SB. Antibody, macrophages, dengue virus infection, shock, and hemorrhage: A pathogenetic cascade. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(Suppl 4):S830-S839.

9 Rico-Hesse R, et al. Molecular evolution of dengue type 2 virus in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:96-101.

10 Green S, et al. Early immune activation in acute dengue illness is related to development of plasma leakage and disease severity. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:755-762.

11 Loke H, et al. Strong HLA class I–restricted T cell responses in dengue hemorrhagic fever: A double-edged sword? J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1369-1373.

12 Mongkolsapaya J, Dejnirattisai W, Xu XN, et al. Original antigenic sin and apoptosis in the pathogenesis of dengue hemorrhagic fever. Nat Med. 2003;921:921-927.

13 Dung NM, et al. Fluid replacement in dengue shock syndrome: A randomized, double-blind comparison of four intravenous fluid regimens. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:787-794.

14 Ngo NT, et al. Acute management of dengue shock syndrome: A randomized double-blind comparison of 4 intravenous fluid regimens in the first hour. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:204-213.

15 Wills BA, Nguyen MD, Ha TL, Dong TH, Tran TN, Le TT, et al. Comparison of three fluid solutions for resuscitation in dengue shock syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005 Sep 1;353(9):877-889.

16 Wills B, Tran VN, Nguyen TH, Truong TT, Tran TN, Nguyen MD, et al. Hemostatic changes in Vietnamese children with mild dengue correlate with the severity of vascular leakage rather than bleeding. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009 Oct;81(4):638-644. 16

17 Vaughn DW, et al. Dengue in the early febrile phase: Viremia and antibody responses. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:322-330.

18 Cao XTP, the Dong Nai Dengue Study Group. The clinical diagnosis and assessment of severity of confirmed dengue infections in Vietnamese children: Is the WHO classification system helpful? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;98(1):65-70.

19 Lanciotti RS, et al. Rapid detection and typing of dengue viruses from clinical samples by using reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:545-551.

20 Lye DC, Lee VJ, Sun Y, Leo YS. Lack of efficacy of prophylactic platelet transfusion for severe thrombocytopenia in adults with acute uncomplicated dengue infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 May 1;48(9):1262-1265.

21 Min MU T, Aye M, et al. Hydrocortisone in the management of dengue shock syndrome. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1975;6:573-579.

22 Sumarmo. The role of steroids in dengue shock syndrome. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1987;18:383-389.

23 Sumarmo, Talogo W, Asrin A, et al. Failure of hydrocortisone to affect outcome in dengue shock syndrome. Pediatrics. 1982;69:45-49.

24 Tassniyom S, et al. Failure of high-dose methylprednisolone in established dengue shock syndrome: A placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Pediatrics. 1993;92:111-115.

25 Futrakul P, et al. Hemodynamic response to high-dose methyl prednisolone and mannitol in severe dengue-shock patients unresponsive to fluid replacement. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1987;18:373-379.