78 Demyelinating Diseases

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

Clinically Isolated Syndrome

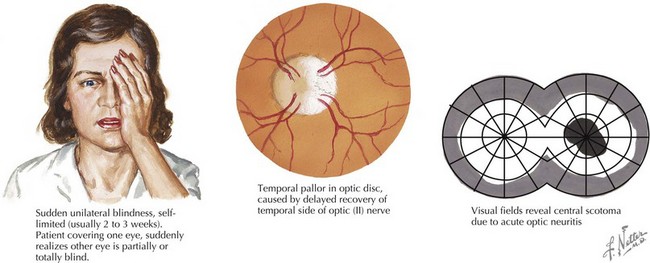

Optic Neuritis

Optic neuritis is characterized by acute or subacute visual loss, altered color vision, periorbital pain that is exacerbated by eye movements, and visual field defects. The neuro-ophthalmologic examination may reveal a relative afferent pupillary defect (in unilateral cases) or optic disc edema (Figure 78-1). MRI of the orbits often reveals T2/FLAIR abnormality in the optic nerve or chiasm with or without enhancement using gadolinium. Visual recovery from idiopathic optic neuritis is excellent for most children, especially in the absence of alternate diagnoses such as NMO.

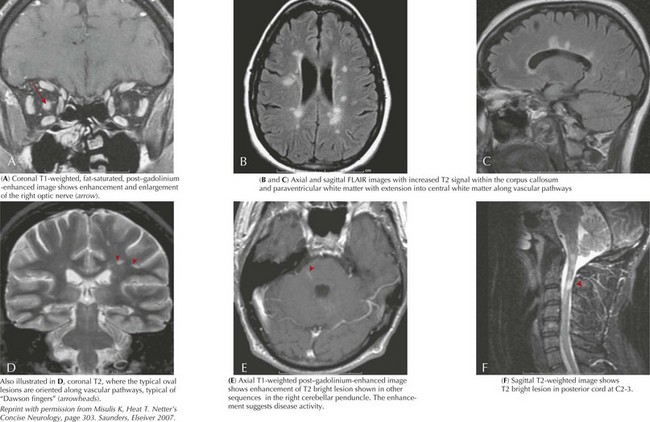

Multiple Sclerosis

MS is a chronic demyelinating inflammatory disorder characterized by the dissemination of neurologic signs and symptoms in time and space in both children and adults. The development of a neurologic symptom lasting more than 24 hours is referred to as an “attack” or “flare.” Children most often present with paresthesias or optic neuritis. Motor dysfunction, ataxia, cranial nerve palsies, vestibular symptoms, and other neurologic symptoms also occur. As described above, a first demyelinating event is called a CIS. The evolution of disease over time affecting multiple areas of the CNS distinguishes MS from a truly monophasic CIS. Using the 2005 Revisions to the McDonald Criteria established for adults, dissemination in time is defined clinically as the separation of symptom onset by 30 days or by the appearance of a new T2 or FLAIR lesion (compared with a reference scan) in the brain or spinal cord on MRI imaging performed at least 30 days after the onset of the initial attack (Figure 78-2). Alternatively, the detection of gadolinium enhancement on a repeat MRI scan performed at least 3 months after the onset of the initial clinical event at a different site (not corresponding to the initial clinical symptoms) also meets criteria for dissemination in time. The IPMSSG suggested that in children a time frame of 3 months be used for both the appearance of a new T2 or FLAIR lesion or gadolinium-enhancing lesion. Dissemination in space is defined by objective clinical evidence of two or more lesions (i.e., two or more abnormalities found on neurologic examination either transiently or permanently). MRI and lumbar puncture can also be performed to document dissemination in space. According to the McDonald criteria and IPMSSG, dissemination in space is fulfilled by three of the following four features: (1) at least one gadolinium-enhancing brain or spinal cord lesion or nine T2 hyperintense lesions in the brain or spinal cord in the absence of a gadolinium-enhancing lesion, (2) at least three periventricular lesions, (3) at least one juxtacortical lesion, or (4) at least one infratentorial or spinal cord lesion. Children are less likely than adults to fulfill these criteria. Therefore, dissemination in space can also be demonstrated in a patient with an MRI showing two or more lesions (one of which must be in the brain) consistent with MS and the presence of oligoclonal bands or an increased IgG index in the CSF. These criteria have not been validated in children but are supported by the IPMSSG and used in clinical practice. Most children have relapsing-remitting MS; primary progressive MS and progressive relapsing MS are rare. Although there are limited data, the natural history of pediatric MS suggests a slower progression of disease than in adults; however, children develop secondary progressive MS at younger ages than adults.

Evaluation and Management

Beak RW, Cleary PA, Anderson MMJr, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of corticosteroids in the treatment of acute optic neuritis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:581-588.

Hahn JS, Pohl D, Rensel M, et al. Differential diagnosis and evaluation in pediatric multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2007;68(suppl 2):S13-S22.

Krupp LB, Banwell B. Tenembaum S, for the International Pediatric MS Study Group: Consensus definitions proposed for pediatric multiple sclerosis and related disorders. Neurology. 2007;68(suppl 2):S7-S12.

Lotze TE, Northrop JL, Hutton GJ, et al. Spectrum of pediatric neuromyelitis optica. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e1039-e1047.

Pohl D, Waubant E, Banwell B, et al. for the International Pediatric MS Study Group: Treatment of pediatric multiple sclerosis and variants. Neurology. 2007;68(suppl 2):S54-S65.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald Criteria.”. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:840-846.

Tenembaum S, Chamoles N, Fejerman N. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a long-term follow-up study of 84 pediatric patients. Neurology. 2002;59:1224-1231.

Transverse Myelitis Consortium Working Group. Proposed diagnostic criteria and nosology of acute transverse myelitis. Neurology. 2002;59:499-505.