15 Dementia

Introduction

Dementia represents a decline in cognitive function not because of impaired level of consciousness. In other words, it reflects a lower level of mental capacity and function than had been the case for a given individual. It demonstrates a process in which intellectual level has deteriorated despite retaining consciousness, thus excluding the confounding variable of delirium. The DSM IV-R diagnosis of dementia includes memory impairment and abnormalities in at least one of the following domains: language; judgment; abstract thinking; performance of tasks; constructional capabilities; or visual recognition.1

What this dictates is a need to document impairment and decline of cognition, namely mental functioning, while concurrently excluding delirium. Delirium may occur consequent to a confusional state associated with interrupted vigilance, incapacity for maintenance of retained thought process, and impaired goal-directed activities.2 Thus delirium may co-exist as a confounding factor and needs to be excluded when diagnosing dementia. Delirium may accompany a host of medical diagnoses as produced by metabolic derangement, exposure to toxins, drug effects (either licit or illicit), infections (either systemic with septicaemia or affecting the central nervous system (CNS) directly), head trauma or peri-ictal epileptic states. It follows that diagnosis of dementia should not be confounded by these concomitant illnesses, although the presence of these conditions, in the absence of any associated delirium, would not exclude dementia.3 Cerebral pathology, resulting in dysphasia or psychiatric disorders, such as depression, also needs to be excluded. This may evoke a picture similar to dementia, resulting in pseudo-dementia.

For a diagnosis of dementia to be considered, the deficit must be of sufficient magnitude to interfere with activities of daily living, work function or other social activities. The diagnosis of dementia does not of itself necessarily imply a specific underlying pathology. Nor does it universally suggest a progressive cause or irreversibility. The diagnosis cannot be applied unless there has been adequate assessment of mental status in the absence of confounding variables, as already defined.

As the population ages and the normal degenerative process continues to affect the population, so too the impact of dementia increases within the community. The incidence or prevalence of dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s disease, increases exponentially with age—effectively doubling with each half decade4 after the age of 60 years. It is said that Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, has an incidence of 1% per annum for those over 65 years of age with a prevalence of approximately 50% in those 85 years and older. It follows that general practitioners will be confronted with dementia in growing proportions and will need to appreciate how to best manage affected patients.5

History

The general practitioner is ideally placed to identify those individuals in whom dementia should be sought (see Box 15.1). They are the best positioned to identify changes in a patient, such as: the well dressed patient who no longer takes pride in their appearance; the patient who no longer attends to personal hygiene; the patient failing to keep routine appointments; or not requesting repeat routine prescriptions for previously stable treatment regimes. These factors should alert the general practitioner, as should repeated minor driving accidents, loss of employment or difficulty coping without an alternative cause.

Box 15.1 Warning signs for dementia

Despite suggestion that general practitioners are perfectly placed to provide the initial diagnosis based on warning signs, less than 40% regularly screen for dementia.6 Often the diagnosis is not initiated by either the doctor or patient but by a concerned family member or close friend who has observed the change in the patient. The patient may present complaining of symptoms of dementia and yet still function so well on official higher centre function tests (see Ch 2), that their complaint is dismissed. Personal experience has taught that ignoring such complaints may be at the patient’s peril. An intelligent patient may be acutely aware of impaired functioning and identify this to the doctor. The doctor may not be able to confirm damage because the patient was well above the norm before noting the decline. The patient may still be above the norm, even allowing for the real decline that has occurred. Personal experience has taught that such a patient deserves a trial of therapy if reporting impaired cognition, in the absence of confounding factors discussed in this chapter. If they report improvement sufficient to justify the patient paying for medication at their own expense, then that is a reasonable option. ‘Willingness to pay’ is an accepted health economic measure, which has relevance within this context. The patient, at this level of functioning, retains the wherewithal to take responsibility for their wellbeing. This type of patient is also able to assess if performance has improved. This approach imposes no cost on society and may allow a patient to remain at an acceptable level of independence for longer.

Where there is doubt about the diagnosis of dementia, it is appropriate to seek the patient’s permission to also interview family and possibly close friends. Such people may be able to report on domestic circumstances, such as neglected cleanliness at home, failure to shop alone or incapacity in activities of daily living—all of which suggest advanced disease. They may also offer more subtle clues, like the attentive spouse who forgot a birthday or wedding anniversary for the first time; the loving grandparent who simply forgot the grandchild’s birthday; or the bridge partner who could no longer be relied upon to make the right bid or play properly.

Examination

The critical examination of the patient with suspected dementia is the testing of higher centre function (see Ch 2). To be able to prescribe pharmacological treatments in Australia requires testing with the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), a tool that has been available for many years.7

Unlike the approach set out in Chapter 2, the MMSE is not used to assess the site of lesion but rather to give an overview of the degree of impairment. The maximal score is 30 and hence a score of 20+ is deemed ‘minimal’ or ‘mild impairment’, a score of 15–19 is classed as ‘moderate’, and less than 14 is considered ‘severe’. The problem with this approach is that the MMSE includes asking the patient to repeat the phrase ‘no ifs, ands or buts’. Even native English-speaking patients may have trouble with this and non-English-speaking patients find it impossible. Some speaking poor English have difficulty differentiating between ‘country’ and ‘state’. Serial 7s are only conducted to 65, which fails to detect subtle change as personal normative data suggests 44 is the cut off (see Ch 2).

The team at Liverpool Hospital in Sydney, Australia, have developed an alternative tool, the Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS),8 which includes six items that assess multiple cognitive domains including memory, praxis, language, judgment, drawing and body orientation.8 This instrument was not assessed by Brodaty and colleagues when recommending an alternative assessment measure, the General Practitioner Assessment of COGnition (GPCOG).6 Personal preference favours the process set out in Chapter 2.

Examination should not be restricted to higher centre function testing but should also explore for other diagnoses known to be associated with dementia (see Box 15.2).

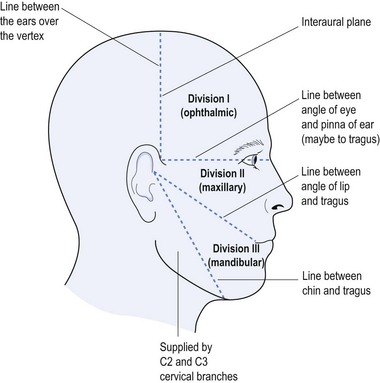

This requires full neurological examination, both cranial nerves and peripheral assessment (see Chs 3 and 4), in addition to higher centre testing. This does not exclude primary causes of dementia, such as: Alzheimer’s disease (the most common primary dementia comprising 50–60% of dementias); fronto-temporal dementia (including what used to be called Pick’s disease); Lewy body dementia (within the Parkinson’s disease spectrum); and the combination of vascular-caused dementia in combination with Alzheimer’s disease (15–20% of those with dementia). There are a number of features that help to differentiate multi-infarct dementia from Alzheimer’s disease (see Table 15.1).

TABLE 15.1 Differentiating multi-infarct dementia from Alzheimer’s disease

| Feature | Multi-infarct dementia | Alzheimer’s disease |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Rapid to abrupt onset | Slower onset |

| Progression |

Investigations

Investigation of the patient with dementia is focused on excluding reversible causes of cognitive decline. Generally speaking, all patients with suspected dementia should have a simple battery of blood tests, including: full blood count; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C reactive protein (CRP); biochemical screening, including electrolytes, renal function, liver function, calcium, lipid profile and blood sugar level; thyroid function; B12 and folate levels; and anti-nuclear and extractable nuclear antibodies.

Generally speaking the general practitioner should look for reversible causes of cognitive decline and dementia, which comprises approximately 1% of cases but when identified and treated provide a profound effect for the patient (see Box 15.3).

Specific Dementias

a Alzheimer’s disease

Alois Alzheimer in 19079 first described the neuropathology of the disease now identified with his eponym. The neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles remain the hallmark of the disease. Originally it was thought to be a disease of the younger dementing patient, but it is now accepted that the pathology is the same for both pre-senile and senile dementing patients.

Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease include advancing age, incidence and prevalence doubling every five years between 65 and 95 years of age. Genetic factors have been recognized—if first-degree relatives have Alzheimer’s disease there is a three to fourfold increased risk.4 Early onset Alzheimer’s disease is associated with the presenilin-1 (PS-1) gene on chromosome 14, the presenilin-2 (PS-2) gene on chromosome 1 and the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene on chromosome 21. A host of mutations have been reported for early onset disease, but this information is offered to whet the appetite rather than expect the general practitioner to undertake genetic testing, which is a highly specialised process.10

The typical pattern of Alzheimer’s disease is thought to be triphasic: (i) slow onset possibly with minimal cognitive impairment (MCI); (ii) accelerated progression where the diagnosis is more obvious; and (iii) severe cognitive deficits interfering with basic activities of daily living and deteriorating to death. There is also a fulminant form of Alzheimer’s disease, which may be confused with prion disease because of its rapid progression to death.11

b Fronto-temporal dementia

Fronto-temporal dementia (previously called Pick’s disease) encompasses a group of degenerative conditions involving a predilection for the frontal and antero-temporal cortex.12 They comprise approximately 10% of dementias but almost half the presenile dementias presenting below 60 years of age. In the late 1990s the fronto-temporal dementias were classified into three groups: the behavioural variant; progressive non-fluent aphasia; and the fluent aphasia–semantic dementia.13

The clinical features of fronto-temporal dementia include: early onset; often there is family history; change in behaviour and personality; problems with language; difficulties with planning, attention and problem solving. Fifty percent of those with fronto-temporal dementia have the behavioural variant, with a 2 : 1 male to female ratio and a mean age at diagnosis of less than 60 years. Personal hygiene is often compromised with ‘concrete’ entrenched thinking, confounded by distractibility, stereotypic behaviour and rapid progression with less than five years’ life expectancy. Approximately 20% have an autosomal dominant inheritance and 15% develop motor neurone disease.

c Dementia with Lewy bodies

Recognition of Lewy bodies as an important component of geriatric dementia is fairly recent, prior to which they were considered mainly as part of the idiopathic Parkinson’s disease picture.14 Patients with dementia with Lewy bodies present with fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations and features of Parkinson’s disease. The dementia affects executive function, with impaired visuospatial skills, memory problems and impaired verbal fluency. Visual hallucinations are common and may be exacerbated by levodopa (the drug of choice for Parkinson’s disease). REM sleep behaviour disorder (see Ch 12) and autonomic problems, such as orthostatic hypotension, are more common.

Treatment is best managed by a consultant, and anti-Parkinsonian treatment is less effective in this group of patients. Anti-psychotic medications used to treat the prominent hallucinations are also often less effective and best left to the specialist.15 There is some evidence as to the effectiveness of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors but again this is best referred to a consultant.

d Other dementias

Vascular dementia is the collection of dementias in which there is clear evidence of diffuse small vessel disease in association with cognitive decline. It is a heterogenous group of dementias for which the approach mirrors that for secondary stroke prevention (see Ch 14).

Other diagnoses, such as Huntington’s disease and those conditions associated with dementia (see Box 15.2), will not be further discussed as the treatment of choice is determined by the underlying condition rather than the dementia per se.

Role of the General Practitioner

The general practitioner is usually the first port of call for the patient with dementia, and the recognition of the symptoms and signs is a vital component of early and appropriate intervention (see Table 15.1).16 The way to deal with the diagnosis, and the appropriate discussion of both treatment and estate planning, should be a partnership between the consultant and family physician.

1 Reisberg B. Diagnostic criteria in dementia: a comparison of current criteria, research challenges, and implications for DSM-V. J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;19:137-146.

2 Adamis D, Sharma N, Whelan PJ, Macdonald AJ. Delirium scales: a review of current evidence [Review]. Aging & mental health. 2010;14(5):543-555.

3 Leposavić I, Leposavić L, Gavrilović P. Depression vs. dementia: a comparative analysis of neuropsychological functions. Psihologija. 2010;43(2):137-153.

4 Stone JG, Casadesus G, Gustaw-Rothenberg K, Siedlak SL, Wang X, Zhu X, et al. Frontiers in Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics. Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 2010;2(1):9-23.

5 Turner S, Iliffe S, Downs M, Wilcock J, Bryans M, Levin E, et al. General practitioners’ knowledge, confidence and attitudes in the diagnosis and management of dementia. Age and Ageing. 2004;33(5):461-467.

6 Brodaty H, Low L, Gibson L, Burns K. What is the best dementia screening instrument for general practitioners to use? American J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(5):391-400.

7 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state.’ A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189-198.

8 Storey JE, Rowland JTJ, Conforti DA, Dickson HG. The Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS): a multicultural cognitive assessment scale. International Psychogeriatrics. 2004;16(1):13-31.

9 Aghaji B. Alzheimer’s disease: a review. J College of Medicine. 2007;12(1):39-44.

10 Ertekin-Taner N. Genetics of Alzheimer’s disease: a centennial review. Neurologic Clinics. 2007;25(3):611-667.

11 Blumbergs P, Beran RG, Hicks PE. Myoclonus in Down’s syndrome: association with Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of Neurology. 1981;38(7):453-454.

12 Grossman M. Frontotemporal dementia: a review. J of International Neuropsychological Society. 2002;8(4):566-583.

13 Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, Passant U, Stuss D, Black S, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1546-1554.

14 Zaccai J, McCracken C, Brayne C. A systematic review of prevalence and incidence studies of dementia with Lewy bodies. Age and Ageing. 2005;34(6):561-566.

15 Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: a review of the evidence. J American Medical Association. 2005;293(5):596-608.

16 Villars H, Oustric S, Andrieu S, Baeyens JP, Bernabei R, Brodaty H, et al. The primary care physician and Alzheimer’s disease: an international position paper. J Nutrition, Health and Aging. 2010;14(2):110-120.