CHAPTER 8 DELIVERING MULTIDISCIPLINARY TRAUMA CARE: CURRENT CHALLENGES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The origins of trauma care delivery are deeply rooted in the major military conflicts of the last century. During the Napoleonic Wars, Dominique Larrey established the concepts of field hospitals, the use of the “flying ambulances” and the principles of triage.1 In World War I, rapid and timely evacuation of the injured from the battlefield through echelons of treatment facilities, each with increasing surgical capabilities, became the standard of care.2 During World War II, in addition to reducing the time from evacuation to treatment, the principle of “resuscitation” or treatment of shock prior to transport evolved. When combined with the other advances in transfusion technology, surgical technique, antibiotics, and so on, this systematic approach to trauma care resulted in a significant decrease in mortality. This approach was further refined in the Korean conflict and the Vietnam War, when wounded soldiers were rapidly transported within minutes by helicopter to fully capable hospitals, where the entire spectrum of trauma care from initial resuscitation to definitive surgical management was delivered.3 Experience gained in the battlefield allowed large, urban medical centers to develop similar paradigms of trauma care for victims of “urban warfare.” However, in spite of extensive training, these same trauma surgeons were unable to provide the same level of care outside these urban hospitals. Therefore, it became clear that the system, and not the individuals, were responsible for the observed successes, and the need for trauma systems, not just trauma surgeons, became recognized.

The publication of the seminal report, Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society, in 1966 became the catalyst in changing the delivery of trauma care. This report highlighted the magnitude of the problem in both human and economic terms and lack of an organized public or governmental response to the problem. As this became a major political issue, Congress responded by enacting the National Highway Safety Act of 1966. The resultant funding spurred the development of trauma systems in the states of Maryland, Florida, and Illinois. Additional federal funding followed passage of Titles 18 and 19 of the Medicare and Medicaid Act, the Emergency Medical Services Systems Act of 1973, and the Emergency Medical Services Amendments of 1976. Prompted by perceived financial gains, a large number of hospitals sought designation as “trauma centers.” With the sharp decline in funding following the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981, the exodus of participating institutions was as rapid as their entry into the system. The specialty care of trauma then became the purview of centers that retained an interest in caring for victims of traumatic injury in spite of the disadvantages that are associated with doing so.4

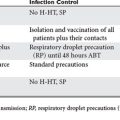

Over the ensuing years, trauma systems have matured with the trauma center as their cornerstone. Adequately addressing the issue of traumatic injury is recognized to include a spectrum beginning with injury prevention and education, throughout the immediate acute care phase, and extending into the rehabilitation. The success of these systems is recognized in the ability of trauma centers, in the context of trauma systems, to reduce mortality and morbidity. Further, lessons learned are being applied in the theater of war. Medical teams on the front lines of battle in Iraq and Afghanistan are receiving training prior to deployment at select trauma centers and employing principles refined in the civilian sector (Figure 1).

In spite of this compelling evolution, the delivery of trauma care continues to face significant challenges (Table 1). Technological advances of the last decade have increased the complexity of care, and require a multidisciplinary approach for an optimal outcome. Such an approach is associated with increasing costs, which in the face of skyrocketing malpractice premiums and declining reimbursements, challenges the financial health of trauma centers. Increased involvement of multiple specialists makes the logistics of providing adequate emergency room coverage and coordination of care a potentially daunting task. The workforce of trained trauma surgeons is shrinking as new graduates from general surgery training programs see trauma, in all but select programs, as a predominantly nonoperative specialty.

Table 1 Key Challenges to Multidisciplinary Delivery of Trauma Care

| Financial | Increasing costs |

| Skyrocketing malpractice premiums | |

| Declining reimbursements | |

| Multispecialty care | Emergency room coverage |

| Coordination of care | |

| Shrinking workforce | Limited trained trauma surgeons |

| Restricted resident work hours | |

| Reduced operative experience | |

| Special considerations | Nutritional support |

| Substance abuse | |

| Neuropsychological support | |

| Rehabilitation | |

| Placement | |

| Special populations | Children |

| Pregnant women | |

| Elderly | |

| Funding | Educational outreach activities |

| Research |

In order to overcome these challenges, we need to redefine the philosophy of trauma surgery and trauma surgeons. The purpose of this review is to describe efforts that are currently under way and other potential solutions currently being entertained to optimize patient care.

ORGANIZING THE INITIAL CARE OF TRAUMA PATIENTS

Prehospital Communication

Direct communication between the trauma center and emergency medical personnel is key.5 The heads-up on the nature and number of arriving trauma victims along with the estimated time of arrival allows for better preparation of required personnel and equipment. This becomes more relevant when multiple casualties are involved, and team members of varying levels of experience are designated according to patients’ severity of injuries. In specific circumstances, it also allows certain specialists to be called in even before the patient arrives (e.g., the neurosurgeon for a traumatic quadriplegia). Activation of “surge capacity” procedures for mass casualty events can be done with the maximum lead time.6 In addition, medical direction can be provided to prehospital personnel in cases outside the realm of those in standard operating procedures.

Tiered Trauma Team Activation

Patients meeting trauma criteria result in activation of a trauma alert. The full complement of providers arrives at the resuscitation bay after being notified. The time before actual patient arrival is utilized to determine what is known about the patient, the likely interventions required, and to reaffirm roles. Members of such a team include the trauma surgeon, trauma fellow/senior surgical resident, junior surgical resident, trauma nurses, physician assistant (PA) anesthesiologists, respiratory technician, and radiology technician. Our current criteria for a trauma alert are enumerated in Table 2. Evaluation and management then follows the principles of the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocols.

| Adult Trauma Alert Criteria | |

| Red criteria | Active airway assistance required |

| Blood pressure <90 systolic or no radial pulse with sustained heart rate >120 | |

| Multiple long-bone fractures | |

| 2nd- or 3rd-degree burns ≥body surface area, amputation proximal to wrist or ankle, penetrating injury to head, neck, torso | |

| Glasgow Coma Scale <12 | |

| Paramedic judgment | |

| Blue criteria | Sustained respiratory rate ≥30 |

| Sustained heart rate ≥120 with radial pulse | |

| Single long-bone fracture due to motor vehicle accident or fall ≥10 feet | |

| Major degloving, flap avulsion >5 inches, gunshot wound to extremities | |

| Best motor response = 5 | |

| Ejection from vehicle (excluding open vehicles) or deformed steering wheel | |

| Age 55 or older | |

| High-Index Criteria | |

| Falls ≥12 feet in adults, and ≥6 feet in children | |

| Extrication time >15 minutes | |

| Rollover | |

| Death of an occupant in the same vehicle | |

| Major intrusion | |

| Ejection from a bicycle | |

| Pedestrian struck by a vehicle | |

| Age 55 or greater | |

| Paramedic judgment |

Note: Presence of one red or two blue criteria constitutes a trauma alert.

For patients with traumatic injuries who do not meet trauma criteria, the designation “high index” is applied. These patients are taken directly to the emergency department (ED). They undergo a similar and thorough trauma work-up under the direction of the ED physician. Once the work-up has been completed, a consultation with the trauma service is obtained. The team reviews findings and the plan of care, and arranges for the necessary follow-up.

On occasion, a high-index patient will be found to have significant injuries or comorbidities that exceed the abilities of the ED physician or the capabilities of the ED. On such occasions, an in-house trauma alert is called, the patient transferred to the resuscitation bay, and the entire team rapidly assembled. Availability of this safety net allows the ED to increasingly participate in the management of the injured. It also reduces the workload imposed on an already busy trauma service, and decreases the costs of an otherwise full activation. It is, however, associated with a more prolonged ED stay, but does not result in suboptimal outcome.7,8

In-House Trauma Attending

It is being increasingly recognized that trauma outcomes are directly related to institutional commitment and not just to the experience of the individual surgeon.9,10 As such, the need for the presence of the trauma attending has been challenged. Attending presence, however, has certain definite advantages. Patient disposition can be more rapid, with real-time interpretation of diagnostic studies and front-end decision making, bypassing the traditional approach of communication along progressive echelons of command. Coordination with other specialists becomes easier with direct attending-to-attending discussions. In institutions where trauma patients may be admitted to services other than the trauma service (e.g., the orthopedic service for isolated orthopedic injuries or the neurosurgical service of isolated neurological injury), the patient may be appropriately arbitrated to the service that will serve the patients interest best. Presence of an in-house trauma attending allows this arbitration to be made after careful consideration of the patient’s trauma burden, preventing admission of trauma patients to nonsurgical services. Finally, attending presence allows for the provision of billing for services, including the initial evaluation and management, surgeon-performed ultrasonography, tube thoracostomy, vascular access lines, and so on.

Captain of the Ship Concept

Over the last two decades, there has been explosive increase in the modalities available for the management of complex injuries.11 The emphasis has been on the development of nonoperative and minimally invasive strategies that involve interventional radiologists and endovascular surgeons, among others.12 Additionally, nontraditional stakeholders such as anesthesiologists (e.g., epidural catheters for pain management in rib fractures) and endoscopists (e.g., endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography/papilotomy for complex liver trauma with bile leaks) are now becoming key players in delivering care.13,14 It is of paramount importance, therefore, to have strong leadership in the trauma service serving as the “captain of the ship,” guiding the patient’s care through the nuances of the various available options, while at the same time, protecting the patient from the need or desire to “push the envelope.”

Trauma Coverage by Specialists

The provision of emergency coverage by specialists has been, and continues to be a major challenge.15,16 On the one hand, tertiary hospitals must provide specialist coverage or risk potential loss of substantial federal and state funding for their trauma centers. At the same time, use of hospitalists to relieve specialists of admissions and the development of alternative venues of practice (e.g., ambulatory surgery centers) have encouraged some specialists, once dependent on hospitals, to reduce or drop their clinical privileges. Change of privilege status from active to courtesy is becoming an increasingly popular option in avoiding provision of emergency coverage. This is further compounded by the skyrocketing malpractice premiums.

Radical changes will be necessary to overcome this problem. Some of the potential solutions to improving emergency coverage by specialists are enumerated in Table 3. Another alternative is to incorporate training of basic emergency procedures used in these specialties into the core trauma curriculum. The dependence on specialties may be reduced with an orthopedic trauma rotation focused on irrigation and debridement of open fractures and application of external fixators, along with a neurosurgical rotation focusing on placement of intracranial monitoring devices, decompressive craniotomies, and evacuation of space occupying lesions, such as subdural or epidural hematomas.17 The ability to provide trauma care on a more elective basis may be appealing and result in increased involvement. It is also our experience that maintaining the care of the patient on the trauma service serves as a strong incentive to motivate participation.

Table 3 Potential Solutions to Improve Emergency Coverage by Surgical Specialists

| Outsource coverage to corporations of multispecialty groups. |

| Pay emergency availability stipend to specialists. |

| Work together at local, state, and federal levels to obtain funding for uninsured or partly insured patients. |

| Establish working networks with hospitals within the jurisdiction to minimize unnecessary transfers and prevent EMTALA violations. |

| Make community leaders aware of the crisis in emergency specialcare through the ist coverage to facilitate a designated tax increase for provision of stipends. |

| Establish a fair on-call schedule among the different specialists. |

| Hospitals need to recognize that the days for free emergency coverage in lieu of maintaining clinical privileges are over. |

| Emergency coverage needs to be a key part when negotiating managed care contracts. |

| Increase the number of hospitalists to reduce the admission burden for specialists. |

| Create additional sources of funding for trauma centers (red light violations, speeding tickets, dedicated taxes, etc.). |

EMTALA, Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act.

ORGANIZING SUBSEQUENT CARE OF TRAUMA PATIENTS

Role of Tertiary Survey

Despite due diligence, the potential for missed injuries exists.18–20 The presence of a low Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) on admission, or the need for pharmacologic paralysis, limits the accuracy of the physical examination, significantly increasing this risk. The most common reason for a missed injury is an inadequate clinical examination. The majority of missed injuries can be identified on repeat clinical assessment with the appropriate imaging studies, especially when a high index of suspicion is maintained. When present, these injuries add to the morbidity and mortality with a less than optimal outcome. It is our routine for the trauma attending to perform a tertiary survey for all patients admitted for more than 24 hours. The task may alternatively be delegated to the trauma surgery fellow or senior surgical resident. It must, however, be performed in all admitted patients, at the prescribed time and in a thorough manner. It includes a complete physical examination and review of all radiological studies.21 Any detected abnormality can be addressed appropriately, with the necessary interventions taken.

Communication

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has mandated that resident duty hours be limited to a maximum 80 hours per week, in-hospital call no more frequent than every third night, and 1 day free of clinical responsibilities for every 7 worked, each averaged over a 4-week period. Since the attending coverage of the service is similarly in blocks of time, usually 24 hours, this results in an increase in the frequency of hand-offs, incurring the risk of communication errors, translating ultimately to medical errors. While computerized medical records are becoming more common, they are not universally available. Current strategies to maintain patient data ranges from pen and paper, to computerized data sheets and the use of personal digital assistants.22 We employ a Microsoft® Excel spreadsheet containing the patient list, key clinical points, and pending tasks. The list is updated several times a day by the surgical resident or the PA and serves as the template for communication during the various rounds. As a means to overcome potential deficiencies in communication we have instituted mandatory group rounds, fostering the exchange of patient information ensuring the continuity of care. These include the morning report, check-out rounds, and the biweekly multidisciplinary rounds (Figure 2).

Morning Report

Every morning at 8 AM, all members of the previous night’s on-call team, the team coming on-call, and other members of the trauma service not engaged in other clinical activities, gather for the morning report. All patients still in the resuscitation area are discussed first. The work-up thus far and pending studies, along with ongoing consultations, are presented and discussed. The senior resident then presents all interesting trauma cases and all trauma cases requiring operative intervention. The emergency surgery consultations are then reviewed in a similar manner. The faculty also utilizes this opportunity to teach, with the use of digitally captured images of injuries and operative findings, as well as computerized radiology imaging software (Figure 3). The use of these multimedia presentations allows for enhanced educational value.23

Multidisciplinary Rounds

In addition to multispecialty medical care, trauma patients present with unique social, financial, and psychological needs. Optimal care and eventual disposition therefore require the active participation of social workers, neuropsychologists, and rehabilitation specialists, among others. It is therefore our practice to conduct biweekly multidisciplinary rounds. Consistency in timing and location of the rounds allows increased participation across the various disciplines. The rounds are led by the most senior trauma attending. Over the course of about 1 hour, all patients on the service are reviewed, issues addressed, and care coordinated. The emphasis is not on therapeutic decisions, but rather on the steps necessary to achieve optimal care and early discharge planning. Issues regarding other disciplines are directly addressed with the representative of that service. Such an approach streamlines care, reduces length of stay, and ultimately decreases the cost of caring for these patients.24 The usual participants in these rounds are listed in Table 4. The trauma performance improvement nurse uses the presentations to identify potential complications and departures from standard of care. Identified issues are then followed up and clarifications sought from the responsible person.

| Trauma services |

| Senior trauma attending |

| Trauma attendings |

| Trauma fellows |

| Residents |

| Physician assistants |

| Trauma program manager |

| Performance improvement nurse |

| Trauma research coordinator |

| Students |

| Rehabilitation |

| Physiatrist |

| Physical therapists |

| Nursing staff |

| ICU charge nurse |

| Trauma floor charge nurse |

| Pharmacists |

| Registered dietitian |

| Infection control nurse |

| Social/case workers |

| Neuropsychologists/addiction specialists |

| Hospital administration representative |

Role of Physician Extenders

Physician extenders, including nurse practitioners and PAs, have taken on a more significant role since the implementation of the 80-hour work-week rule by the ACGME in 2003.25 As previously discussed, with these new requirements, residents are no longer able to provide the same continuity of care as in the past. The incorporation of physician extenders into our practice has allowed us to maintain the necessary continuity.26 When well-trained and properly supervised, they function as mid-level residents. In addition to assisting with patient care, they are able to orient new fellow/residents to the routines and the protocols of the service. They act as liaisons with the various services coordinating care and executing decisions made at rounds. They secure supplies, obtain consents, and assist with the performance of procedures such as placement of lines, feeding tubes, tracheotomies, vena caval filters, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomies, and so on. By virtue of their consistent presence in the unit, or on the floor, they are able to provide families with frequent updates on the status of the patient. The rapport established with the family has been found to be extremely beneficial during family meetings regarding the care of complex, critically ill patients. Their consistent presence expedites patient disposition, translating into a shorter ICU and hospital length of stay. The resultant streamlining of care results in cost savings that offset the expenditures of hiring physician extenders. Further, their schedule can be arranged to complement that of the residents on the service. This leads to team members always being available, reducing the potential for medical errors that otherwise result from a failure to review studies and obtain appropriate follow-up. Their incorporation into a given setting is dependent on state law, level of training, experience, and especially, the level of supervision.

Next Generation of Trauma Surgeons

A significant shortage of fellowship-trained trauma surgeons reflects the current attitudes of graduating general surgery residents toward the specialty.27,28 The most common reasons cited for this include heavy workload, decreasing number of operative cases, nonoperative nature of the surgical critical care fellowship, night work, the perception of increased exposure to viral infections, and litigation.17

Working Hours

The workload of practicing trauma surgeons has significantly increased since the adoption of the 80-hour work-week rule for residents, the increase in trauma incidence, and a greater need for documentation. The increased time spent on routine clinical care has come at the cost of the pursuit of academic activities, such as research and publications, and often impacts the quality of personal lives.29 Potential solutions include the incorporation of physician extenders to assist with delivery of routine clinical care, adoption of computerized mobile documentation technologies, and the addition of additional faculty members. The coupling of trauma with surgical critical care is a financially viable option. In addition to the critical care for trauma patients, the service must strive to provide the critical care needs of all surgical patients at their institution. This is beneficial in several ways. First, the higher reimbursements would augment the financial viability of the service. Second, there is physiologic similarity between the severely injured and the critically ill surgical patients; management of these patients is not only intellectually stimulating, but also lessons learned from one group to be applied to the other. Finally, a period of time dedicated to the ICU allows recovery from the time spent on a busy trauma rotation, potentially reducing burnout.

Workload reduction can also be achieved by the fair distribution of trauma patients.30 Patients with multisystem trauma clearly belong on the trauma service, under the care of the trauma surgeon. Patients with injuries isolated to a single system may, however, be adequately managed by subspecialty services after a complete and comprehensive trauma evaluation. This has been made possible by the availability and aggressive use of whole-body computed tomography (CT) scanning. Examples include isolated skeletal injuries; isolated traumatic brain or spinal cord injury; and isolated facial fractures that may be admitted to orthopedic, neurosurgical, and maxillofacial services, respectively. All patients must, however, undergo a complete trauma work-up to rule out other injuries, and the trauma service must always remain available to assist with care when requested. Minor injuries to other organ systems do not preclude admission to the subspecialty service. As a measure to reduce missed injuries, all patients admitted to subspecialty services are re-evaluated with a tertiary survey performed by the trauma service at 24–48 hours. In addition, these patients are separately flagged and their outcomes reviewed at the monthly trauma quality management and performance improvement meeting.

Trauma as a Nonoperative Specialty

The incidence of penetrating trauma is on the decline. In all but a handful of select trauma centers, the majority of trauma is blunt and can be managed nonoperatively. Often when patients do require surgical intervention, it is by other specialties (orthopedics, neurosurgery, reconstructive surgery, etc.). The dwindling true surgical opportunities have resulted in career dissatisfaction among current trauma surgeons. It is also having a negative impact on current graduates of general surgical residency programs. First, residents are graduating with only nominal operative trauma experience. Second, other specialists perceive trauma as a nonoperative specialty or surgical internists who prepare patients for operative procedures.31

The emergence of the field of acute care surgery and redefinition of the trauma surgeon and the acute care surgeon may help overcome the lack of operative opportunity.32,33 The balance achieved will allow for an adequate number of cases that maintain operative skills and career satisfaction. Also, patients seen in the acute setting after evaluation may be found to be candidates for elective surgery for either related or unrelated procedures. Development of collaborations may also serve to increase the opportunity for elective surgery. Close relations with the hospitalists have made the trauma service the routine provider of all general surgery services for this group at our institution. The field, however, needs to be clearly defined. In its current vague form, we run the risk of being given ownership of cases that the elective services do not wish to be involved with. This may be on the basis of the patient’s insurance status, the nature of the disease, or the time of day. We need to remain vigilant for the potential of becoming the “dumping ground.”34 Another alterative is to include within the trauma fellowship advanced training in a defined field of general surgery that would allow for the development of a limited elective general surgical practice. Focused advanced laparoscopy, endocrine surgery, and endovascular surgery are potential fields that may be explored.

Operative Trauma Education

Over the past two decades, the incidence of penetrating trauma has sharply declined. Also, with better imaging techniques such CT, adoption of modalities such as ultrasonography, adoption of nonoperative strategies for solid organ injuries, and the development of minimally invasive techniques, the management of blunt trauma is essentially nonoperative. General surgery residents are graduating with progressively decreasing operative trauma experience. Innovative educational strategies are therefore of paramount importance. The advanced trauma operative management (ATOM) course is one such useful tool.35,36 Developed by Lenworth Jacobs at the University of Connecticut, Hartford, the course has been enthusiastically adopted at the University of Miami, where it has been regularly offered since 2004. Held over the course of a single day, it begins with six didactic lectures on operative techniques for the various organs of the abdomen and thorax. The subsequent live laboratory section involves the use of approximately 50-kg swine as the trauma model. One instructor and one student are assigned to each animal to maximize the learning experience (Figure 4). After performance of a trauma laparotomy where the anatomical differences between the swine and human are pointed out, the student leaves the table. The instructor then creates a standard defined set of injuries. On return of the student, they are given a mechanism and must explore the animal, identify the injuries and perform the appropriate operative repair. Throughout this process, the instructor quizzes the student on various aspects of the particular injury. The course is currently offered to all senior (PGY-4, PGY-5) surgical residents and trauma fellows. While enthusiasm for the course is uniform, it is greatest among the critical care fellows who have been out of the operative arena for a time and appreciate the opportunity to practice prior to their return to the trauma service.

The nonoperative nature of the surgical critical care fellowship becomes even more emphasized when one considers that the resident’s maximal operative experience, both in terms of the number and type of cases, comes in their year as chief resident. The abrupt deterioration to the “nonoperating intensivist” can therefore have a profound impact. In recent years, we have encountered a small number of fellows who elect to discontinue their critical care fellowship and pursue fellowships in other operative disciplines. The development of a curriculum that allows for periodic return to operative services may help overcome this deficiency. Alternatively, change in regulations that allow for trauma or emergency general surgery call, while on critical care rotations may be feasible. The approach, however, must be tailored to the critical care load and needs of the individual institution, as it is certain that a one-size-fits-all approach will not meet the best interests of the trainee and the patient.37

OTHER CHALLENGES IN ORGANIZING TRAUMA CARE

Alcohol and Substance Abuse

Use, abuse, or dependence on alcohol lies at root of many traumatic injuries and complicates management resulting in poor outcomes.38 In addition, the resulting abrupt cessation of drinking that results from hospitalization may precipitate alcohol withdrawal syndrome. It may range from anxiety and increased irritability in its mild form to seizures or delirium tremens when severe. The symptoms most commonly begin 48–72 hours after abrupt cessation and usually peak at 5 days. Patients who develop alcohol withdrawal syndrome have more ICU days, ventilator days, and hospital days, develop more morbidities, and ultimately incur greater hospital costs.39 Recognition of the pervasive presence of alcohol in our patient population has led us to incorporate a neuropsychologist specializing in addiction disorders into our trauma service. At initial evaluation, all patients are screened for potential alcohol or substance abuse. High-risk patients are placed on short-acting benzodiazepines, clonidine, and their maintenance intravenous fluids are supplemented with thiamine and folate. The neuropsychologist performs a formal evaluation and administers a brief intervention.40,41 They also assist with tailoring the narcotic medication needs of this group of patients, which can often be challenging. The entry of patients into support and detoxification programs on discharge is also coordinated. We have also identified issues with substance abuse in patients who have become habituated to narcotics used to treat injuries during their current hospitalization. These patients do not have a history of preinjury drug use and have been fully functional prior to the event. Neuropsychological intervention in addition to strategies such as gradual tapering, use of drugs with lesser narcotic potency, and use of non-narcotics are generally successful.

Social and Financial Issues

A good proportion of trauma patients are designated self-pay, which in essence translates into “unable to pay.” The frequency of self-pay patients has been noted to be higher in pedestrians hit by motor vehicles and victims of penetrating trauma. These patients are often more severely injured and cost more to care for. At the same time, they often lack the social and financial support necessary to fully recover from the injury after discharge from the acute care setting. Questionable immigration status further compounds the problem, limiting the rehabilitation facilities that are able to accept these patients. To alleviate some of these issues, an experienced case worker is assigned to each patient immediately after admission. Case workers serve as patient advocates, assisting them with obtaining the best postdischarge support possible. Also, during each multidisciplinary round, the eventual disposition of each patient is addressed. Barriers to discharge can therefore be identified early and alternatives sought.42

REHABILITATION AND FURTHER DISPOSITION

With improvements in trauma care, the focus has sifted from mere survival to an optimal functional recovery from the traumatic event.43 This functional recovery often requires months or even years of rehabilitation as in the case of traumatic brain injury or spinal cord injury. The costs of such therapy are therefore substantial, and may in cases even exceed those of the acute phase of care. Several measures to evaluate functional outcome have been validated and include the Functional Independence Measure (FIM), Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS), the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), and the modified FIM. Periodic analysis of these outcome measures serves as a useful benchmark for the quality of trauma care being delivered. Although poor follow-up by trauma patients is a recognized limitation, we utilize the SF-36 to monitor functional outcome.

NUTRITIONAL SUPPORT

Multisystem trauma is a highly catabolic state; resultant nutritional deficiencies compound the systemic immunosuppression that results due to the injury itself.44 The situation is made worse by pre-existing malnutrition that is not uncommon in the trauma population. Certain groups are especially at risk, including those who abuse alcohol or use drugs, the elderly, and patients with open abdomens following damage control operations.45 While several aspects of nutritional support remain controversial, such as the use of immunonutrition, several generalizations can be made. Nutritional support is best started early, once resuscitation has been completed. Enteral nutrition is the preferred route when a functional gastrointestinal tract is available.46 Total parenteral nutrition is employed when the gastrointestinal tract is not available and function is not expected to return for over a week. While the best parameter to monitor the adequacy of nutritional support is still debatable, prealbumin remains our current choice. The influence of an elevated C-reactive protein level that is almost invariably present in critically ill trauma patients needs to be determined. A pharmacist specialized in nutrition is an integral part of our trauma team. The pharmacist determines initial nutritional requirements, assists with selection of the best formulation to use, and monitors nutritional parameters.

POPULATIONS AT RISK

Geriatric Population

The elderly are the fastest-growing segment of the population. Additionally, improvement in general well-being has allowed this group to participate in activities beyond that which were customary. This will likely result in a significant increase in elderly trauma patients who will require care. The American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACS-COT) recommends that patients over 55 years of age should be considered for transport to a trauma center. This recommendation is based on the finding that there is a sharp increase in mortality that occurs at this age independent of injury severity, mechanism, and body region involved. The basis for this disproportionate mortality has not been clearly elucidated. Postulated factors that may be responsible include decreased physiologic reserve, presence of pre-existing medical conditions, use of certain medications, and the greater degree of injury sustained in impacts of lesser severity. It is our practice to have a very low threshold to admit these patients to the ICU, to use invasive hemodynamic monitoring, and to obtain subspecialty medical consultations.47 The reduced functional capabilities impede the functional recovery from the traumatic event. A rehabilitation service consultation is obtained early in the hospital course to assess needs. Social services are also recruited early to assess the family support structure. Disposition in the majority of cases is to a rehabilitation or long-term care facility.

Obstetric Trauma Patients

On receiving report of an incoming pregnant trauma patient, in addition to the trauma team, the in-house obstetric resident and attending are paged. The trauma team manages initial resuscitation. Special emphasis is placed on administering supplemental oxygen and tilting the long spine board to take pressure off the inferior vena cava in gestations of over 20 weeks. Once the primary survey has been performed according to guidelines, a secondary survey is performed. In addition to assessing for nonobstetric injury, the fetal heart tones are assessed and a speculum examination performed. In the absence of fetal heart tones, no further fetal resuscitation is indicated. When fetal heart tones are present, the duration of gestation is estimated. If less than 24 weeks, routine maternal trauma care is provided. If more than 24 weeks, electronic fetal monitoring is instituted, and after completion of the trauma work-up the patient is admitted to the obstetric unit for continued observation. The speculum examination is performed to assess for spontaneous rupture of membranes and vaginal bleeding. The trauma service continues to follow the patient for the entire duration of their hospitalization. For patients requiring emergent nonobstetric operative interventions, intraoperative electronic fetal monitoring is carried out during the entire procedure with an obstetric nurse in attendance for gestations that have reached viability. The obstetric team remains on alert should fetal decelerations develop. For gestations that have not reached viability, fetal heart tones are documented before and after the operation.48 To reduce radiation exposure, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to clear the spine when this cannot be safely achieved clinically.

Pediatric Population

Children are not little adults. They have unique anatomic physiologic and anatomic features that must be recognized when delivering trauma care.48 The outcome of pediatric trauma is therefore best when the injured child is cared for in centers with the necessary capabilities. In addition to the trauma team, the senior pediatric surgery resident and pediatric intensive care fellow are paged on receipt of the trauma alert. Once the primary survey and initial resuscitation have been completed, further work-up is delegated to the senior pediatric surgery resident, under the supervision of the pediatric surgery attending. Admission when necessary is made to the pediatric floor or pediatric ICU (PICU). In centers lacking a residency program, a pediatric emergency room physician and PICU nurses are useful resources to enlist in providing pediatric trauma care.

FUNDING FOR EDUCATIONAL OUTREACH AND RESEARCH

In spite of being the leading cause of death between ages 1 and 44, and resulting in the greatest loss in years of productive life, trauma education and research sadly lags behind that for cancer, heart disease, and stroke. Also, largely as a result of the poor payer mix, increased use of sophisticated technologies, and improvements in critical care science that allow more critically injured trauma patients to survive, most trauma center are in the middle of a financial crisis. Meager resources are directed toward providing patient care. As a consequence, providing educational outreach activities and performing research have become even more challenging.49 Innovative funding sources need to be identified. Potential sources include revenues generated from red-light violations and speeding tickets, dedicated taxes, and grants from corporations and foundations. Additionally, the public needs to be educated on the enormity of the problem, the value of trauma centers and systems, and the needs of the future. Strong public opinion may sway lawmakers to give the trauma system its due.

1 Skandalakis PN, Lainas P, Zoras O, Skandalakis JE, Mirilas P. “To afford the wounded speedy assistance”: Dominique Jean Larrey and Napoleon. World J Surg. 2006;30(8):1392-1399.

2 Hawk R. Military medicine comes of age. The First World War. J Fla Med Assoc. 1992;79(5):309-313.

3 King B, Jatoi I. The mobile Army surgical hospital (MASH): a military and surgical legacy. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(5):648-656.

4 Mullins RJ. A historical perspective of trauma system development in the United States. J Trauma. 1999;47(Suppl 3):S8-S14.

5 Gerndt SJ, Conley JL, Lowell MJ, Holmes J, et al. Prehospital classification combined with an in-hospital trauma radio system response reduces cost and duration of evaluation of the injured patient. Surgery. 1995;118(4):789-794.

6 Doyle CJ. Mass casualty incident. Integration with prehospital care. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1990;8(1):163-175.

7 Eastes LS, Norton R, Brand D, Pearson S, Mullins RJ. Outcomes of patients using a tiered trauma response protocol. J Trauma. 2001;50(5):908-913.

8 Tinkoff GH, O’Connor RE, Fulda GJ. Impact of a two-tiered trauma response in the emergency department: promoting efficient resource utilization. J Trauma. 1996;41(4):735-740.

9 Durham R, Shapiro D, Flint L. In-house trauma attendings: is there a difference? Am J Surg. 2005;190(6):960-966.

10 Helling TS, Nelson PW, Shook JW, Lainhart K, Kintigh D. The presence of in-house attending trauma surgeons does not improve management or outcome of critically injured patients. J Trauma. 2003;55(1):20-25.

11 Pilgrim CH, Usatoff V. Role of laparoscopy in blunt liver trauma. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(5):403-406.

12 Kawamura S, Nishimaki H, Takigawa M, Lin ZB, et al. Internal mammary artery injury after blunt chest trauma treated with transcatheter arterial embolization. J Trauma. 2006;61(6):1536-1539.

13 Bajaj JS, Spinelli KS, Dua KS. Postoperative management of noniatrogenic traumatic bile duct injuries: role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopan-creaticography. Surg Endosc. 2006;20(6):974-977.

14 Lubezky N, Konikoff FM, Rosin D, Carmon E, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy and temporary internal stenting for bile leaks following complex hepatic trauma. Br J Surg. 2006;93(1):78-81.

15 McConnell KJ, Johnson LA, Arab N, Richards CF, et al. The on-call crisis: a statewide assessment of the costs of providing on-call specialist coverage. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;13(1):727-735.

16 Glabman M. Specialist shortage shakes emergency rooms: more hospitals forced to pay for specialist care. Physician Exec. 2005;31(3):6-11.

17 Spain DA, Miller FB. Education and training of the future trauma surgeon in acute care surgery: trauma, critical care, and emergency surgery. Am J Surg. 2005;190(2):212-217.

18 Biffl WL, Harrington DT, Cioffi WG. Implementation of a tertiary trauma survey decreases missed injuries. J Trauma. 2003;54(1):38-43.

19 Houshian S, Larsen MS, Holm C. Missed injuries in a level I trauma center. J Trauma. 2002;52(4):715-719.

20 Brooks A, Holroyd B, Riley B. Missed injury in major trauma patients. Injury. 2004;35(4):407-410.

21 Hoff WS, Sicoutris CP, Lee SY, Rotondo MF, et al. Formalized radiology rounds: the final component of the tertiary survey. J Trauma. 2004;56(2):291-295.

22 Van Eaton EG, Horvath KD, Lober WB, Rossini AJ, Pellegrini CA. A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign-out system on continuity of care and resident work hours. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200(4):538-545.

23 Cohn S, Dolich M, Matsuura K, Namias N, et al. Digital imaging technology in trauma education: a quantum leap forward. J Trauma. 1999;47(6):1160-1161.

24 Dutton RP, Cooper C, Jones A, Leone S, et al. Daily multidisciplinary rounds shorten length of stay for trauma patients. J Trauma. 2003;55(5):913-919.

25 Oswanski MF, Sharma OP, Raj SS. Comparative review of use of physician assistants in a level I trauma center. Am Surg. 2004;70(3):272-279.

26 Christmas AB, Reynolds J, Hodges S, Franklin GA, et al. Physician extenders impact trauma systems. J Trauma. 2005;58(5):917-920.

27 Chiu WC, Scalea TM, Rotondo MF. Summary report on current clinical trauma care fellowship training programs. J Trauma. 2005;58(3):605-613.

28 Shackford SR. The future of trauma surgery—a perspective. J Trauma. 2005;58(4):663-667.

29 Esposito TJ, Leon L, Jurkovich GJ. The shape of things to come: results from a national survey of trauma surgeons on issues concerning their future. J Trauma. 2006;60(1):8-16.

30 Rogers F, Shackford S, Daniel S, Crookes B, et al. Workload redistribution: a new approach to the 80-hour workweek. J Trauma. 2005;58(5):911-914. discussion 914–916

31 Fakhry SM, Watts DD, Michetti C, Hunt JP. EAST Multi-Institutional Blunt Hollow Viscous Injury Research Group: The resident experience on trauma: declining surgical opportunities and career incentives? Analysis of data from a large multi-institutional study. J Trauma. 2003;54(1):1-7. discussion 7–8

32 Ciesla DJ, Moore EE, Moore JB, Johnson JL, et al. The academic trauma center is a model for the future trauma and acute care surgeon. J Trauma. 2005;58(4):657-661. discussion 661–662

33 Austin MT, Diaz JJJr, Feurer ID, Miller RS, et al. Creating an emergency general surgery service enhances the productivity of trauma surgeons, general surgeons and the hospital. J Trauma. 2005;58(5):906-910.

34 Ciesla DJ, Moore EE, Cothren CC, Johnson JL, Burch JM. Has the trauma surgeon become house staff for the surgical subspecialist? Am J Surg. 2006;192(6):732-737.

35 Jacobs LM, Burns KJ, Kaban JM, Gross RI, et al. Development and evaluation of the advanced trauma operative management course. J Trauma. 2003;55(3):471-479.

36 Jacobs LM, Burns KJ, Luk SS, Marshall WT3rd. Follow-up survey of participants attending the Advanced Trauma Operative Management (ATOM) Course. J Trauma. 2005;58(6):1140-1143.

37 Richardson JD, Franklin GA, Rodriguez JL. Can we make training in surgical critical care more attractive? J Trauma. 2005;59(5):1247-1248. discussion, 1248–1249

38 Walsh JM, Flegel R, Cangianelli LA, Atkins R, et al. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among motor vehicle crash victims admitted to a trauma center. Traffic Inj Prev. 2004;5(3):254-260.

39 Bard MR, Goettler CE, Toschlog EA, Sagraves SG, et al. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome: turning minor injuries into a major problem. J Trauma. 2006;61(6):1441-1445.

40 Sommers MS, Dyehouse JM, Howe SR, Fleming M, et al. Effectiveness of brief interventions after alcohol-related vehicular injury: a randomized controlled trial. J Trauma. 2006;61(3):523-531.

41 Gentilello LM, Rivara FP, Donovan DM, Jurkovich GJ, et al. Alcohol interventions in a trauma center as a means of reducing the risk of injury recurrence. Ann Surg. 1999;230(4):473-480.

42 FitzPatrick MK, Reilly PM, Laborde A, Braslow B, et al. Maintaining patient throughput on an evolving trauma/emergency surgery service. J Trauma. 2006;60(3):481-486. discussion 486–488

43 PA Cameron, BJ Gabbe & JJ McNeil: The importance of quality of survival as an outcome measure for an integrated trauma system. Injury 37(12): 1178–1184

44 Hasenboehler E, Williams A, Leinhase I, Morgan SJ, et al. Metabolic changes after polytrauma: an imperative for early nutritional support. World J Emerg Surg. 2006;1:29.

45 Cheatham ML, Safcsak K, Brzezinski SJ, Lube MW. Nitrogen balance, protein loss, and the open abdomen. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(1):127-131.

46 Kozar RA, McQuiggan MM, Moore EE, Kudsk KA, et al. Postinjury enteral tolerance is reliably achieved by a standardized protocol. J Surg Res. 2002;104(1):70-75.

47 Jacobs DG. Special considerations in geriatric injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2003;9(6):535-539.

48 Kuczkowski KM. Trauma in the pregnant patient. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2004;17(2):145-150.

49 Nagel RW, Hankenhof BJ, Kimmel SR, Saxe JM. Educating grade school children using a structured bicycle safety program. J Trauma. 2003;55(5):920-923.