Chapter 8. Deliberate self-harm, alcohol and substance abuse

Care of the unconscious patient: ABCDE282

The patient who refuses treatment287

Cocaine303

Ecstasy303

Heroin abuse305

Needle stick injuries308

Hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections309

Violent incidents309

Deliberate Self-Harm

General Principles

Principles of treatment

• Appropriate emergency management to ensure the safety of the patient

• Granting the same care, respect and privacy as any other patient

• Proper psychosocial assessment

• Identification of patients at risk from further self-harm

• Where possible, the patient should be given the choice of a male or female member of staff to assess them and provide the care

Who Commits Suicide?

There are 5000 suicides per year in England and Wales: 45% by violent methods, mainly jumping from heights, strangulation and drowning; and 35% by drug overdose, predominantly antidepressants and paracetamol. Interestingly, the rates in both sexes are falling throughout the age range. Numerous factors are said to contribute to this: higher employment rates, recent initiatives to counteract self-harm, and reduction in carbon monoxide levels in exhausts. There is still concern, however, over rates in young males, which, compared with two decades ago, are particularly high.

Who is at a particularly high risk of suicide?

It is important to be aware of the vulnerable groups, because they will be encountered on the acute medical wards as a result of self-harm or because of their high rates of poor overall physical health.

• Schizophrenia, especially in patients who are poorly compliant or lost to follow-up

• History of drug and alcohol abuse

• Any patient who says that they are feeling suicidal, especially if accompanied by feelings of hopelessness

• Patients living in social isolation with no family support

• Several previous episodes of deliberate self-harm (25% of successful suicides have tried before within the past year)

• Asingle episode of deliberate self-harm carries 1 in 20 rate of suicide within 10 years

Which Type of Patients are Admitted With Deliberate Self-Harm?

The admission rate for deliberate self-harm is 300 per 100 000 of the population per year and is increasing, particularly among males aged 15–24 years.

• The average age is 30 years

• 40% will have taken a previous overdose

• 20% will take a further overdose within a year, particularly those

— who have a history of alcohol and substance abuse

— who discharge themselves before the initial assessment has been completed

— who have had several previous episodes

• Social deprivation and social isolation are common

• Up to 10% will have a serious psychiatric disorder, commonly depression

• There is a strong link with a history of epilepsy, particularly in males

• There is often a history of early parental death or separation

• Aquarter will have been in contact with the psychiatric services

• Common triggers are major domestic arguments or a recent separation

The embarrassed and impulsive

• The spur of the moment

• Often triggered by a row and alcohol

• Not necessarily a trivial amount, often paracetamol

• Low risk of recurrence or future suicide

The serious attempt

• A planned event

• Carried out alone and in secret

• No attempt to get help

• Suicide note

• Admits to the intended outcome

• Even ‘trivial’ overdoses may represent a determined attempt at suicide

The high-risk self-harm

• Older

• Male

• Isolated

• Unemployed/retired

• Alcohol dependence

• Poor general health

• Violent method used

• Repeated attempts

• Suicide note

Why do Patients Deliberately Harm Themselves?

• To gain temporary respite – ‘I just wanted to get some sleep/escape/to get away for a while’

• As a cry for help – ‘I didn’t know what to do next/where to go/who to turn to’

• As a signal of distress – ‘Nobody listened/I just couldn’t explain what was happening to me’

• Communicating anger/eliciting guilt/influencing others

— ‘I did it on the spur of the moment in front of them all’

— ‘This will show her/him what it’s been like for me’

• To end their lives – ‘There’s no point in any of it any more’

Two high-risk patients

Case Studies 8.1 and 8.2 illustrate different types of self-harm cases.

Case Study 8.1

A 40-year-old man was admitted with an overdose of one of the newer less toxic antidepressants.

He complained of feeling generally upset and lonely, but denied significant past illnesses. He was single and lived alone, visiting his father at weekends. He presented as an outwardly cheerful, middle-class articulate man who could not really account for the overdose. Nothing else was noted in the medical or nursing notes.

On subsequent very close questioning, he admitted to previous problems with depression and recalled having ECT in his 20s after a period when he thought he was going mad. He had been treated with antipsychotics at that time.There was a history of progressive social isolation, with only occasional visits away from his bedsit to visit his father.

Case Study 8.2

A 75-year-old man with severe ischaemic heart disease, cardiac failure and persistent hypotension was admitted because of self-harm.

He had become increasingly frustrated and angry with an unexplained pain in his lower abdomen, which had been thoroughly investigated. He was feeling low and had been sleeping badly. He went into the kitchen, took the scissors, and made multiple superficial incisions across his upper abdomen to ‘relieve the blood congestion’. On admission, he was tearful and frustrated, but embarrassed to have caused so much trouble.

From Case Study 8.1 it is clear that:

• the history needed unearthing

• this patient had a long unrecognised history involving a major psychosis: probably schizophrenia

The man in Case Study 8.2 is at very high risk:

• elderly male

• violent method of self-harm

• features of depression

• failing physical health

In this age group, deliberate self-harm is commonly triggered by disability, social isolation, chronic pain and untreated depression. It is important to recognise symptoms of depression in the elderly:

• anorexia and weight loss

• constipation

• change in sleep

• pattern of mood swings, especially early morning depression

• physical and mental slowing

• suicidal ideas

Because the highest rates of suicide are seen in elderly men, it is generally routine to refer for psychiatric assessment any patient older than 65 years who is admitted with self-harm. Such an act, in the over-65s, signifies significant suicidal intent.

Nursing the Patient in Self-Harm

Acute Medical Assessment Units should have internet access to TOXBASE the UK database of the National Poisons Information Service. This provides detailed descriptions of the management of individual clinical problems.

Critical nursing tasks in deliberate self-harm

Take appropriate blood and urine tests

Assuming, after the initial assessment, that the patient does not need to be transferred to the HDU, steps should be taken to decontaminate the gut.

Decontamination of the gut

Gastric lavage. Gastric lavage is no longer indicated as routine in self-poisoning. Occasionally it is used:

• within the first hour of ingestion (particularly with iron tablets or lithium)

• if the airway is secure

• if a potentially life-threatening overdose has been taken

Activated charcoal

Single dose. A single oral dose of 50g activated charcoal enhances the elimination of several drugs and is used when anything more than a trivial amount has been taken (accepting the unreliability of the history in this group of patients). It is most effective when given within an hour of the overdose.

It is most useful in:

• paracetamol

• tricyclics

• aspirin

• theophylline

• phenytoin

• carbamazepine

• digoxin

It is of no value in poisoning with:

• iron tablets

• lithium

• methanol

• antifreeze

To avoid the risk of aspiration, the airway must be secure before charcoal is used: it may be necessary to administer MDAC via a nasogastric tube.

Repeated vomiting reduces the effectiveness of charcoal treatment, so antiemetics such as i.v. cyclizine 50mg 4-hourly or i.v. ondansetron may be indicated.

Experimental and new treatments. Recent advances in the treatment of self-poisoning include a new antidote for methanol and antifreeze poisoning: 4-methylpyrazole. Whole-bowel irrigation with polyethylene glycol is used for serious overdoses of enteric-coated drugs, iron-containing compounds or sustained-release preparations.

Important nursing tasks in deliberate self-harm

Ensure that all the relevant information is available

If the patient is unable to give a reliable history but there is a strong suspicion of self-harm:

• What is available to the patient?

— the patient’s usual medication, including insulin

— other tablets and medications at home

— illicit and recreational drugs

• Is there evidence of self-poisoning

— empty bottles, blister packs, foil wrappers

— has alcohol been involved?

• Is there a suicide note?

Other information from the patient or relatives. The key pieces of information needed in the patient’s history are listed in Box 8.1.

Box 8.1

The history must include:

• Mental state

• Past psychiatric history

• Previous self-harm

• Alcohol use

• An assessment of suicidal intent

Confidentiality. When dealing with the patient’s family, the clinical need to know the nature and timing of the overdose must be balanced against the patient’s right to confidentiality. There may be sensitive matters that the patient would not want to disclose to a third party. Common issues in this area include extramarital relationships, serious difficulties at work, unwanted pregnancy and conflict over child custody.

Relevant medical history

• Heart disease (tricyclics trigger arrhythmias)

• Liver disease (increases the risk of liver damage with paracetamol)

• Alcohol abuse (liver damage and a marker for high suicidal intent)

• Chronic disability (increases the likelihood of significant depression)

Psychosocial history

• The sequence of events that triggered the overdose

• Psychiatric history, especially of depressive illness

• Domestic situation and family support:

— marital status

— who else lives in the home

— names and ages of children and who is caring for them

— recent bereavements, anniversaries of deaths

— has the patient a social worker/community psychiatric nurse?

• Previous self-harm

• Are there any vulnerable children/possible abuse? This requires urgent attention

• Job and financial worries

• Alcohol or drug abuse

• Evidence of domestic violence – it is acceptable to ask directly about possible abuse by a partner

• Recent childbirth

• Is there still suicidal intent?

Provide a suitable and safe environment in which to recover consciousness

• Physical safety is ensured from the use of the recovery position combined with appropriate monitoring of the consciousness level and the vital signs

• It is important to maintain a calm, competent and non-judgemental approach. You are dealing with a very vulnerable group with low self-esteem, high stress levels, guilt about ‘wasting everybody’s time’ and perhaps just extreme embarrassment

• Organise appropriate communication with the mental health liaison nurse or social services, who can provide effective help

• Listen to the patient. Try and understand why the patient took the overdose at that particular time and with what intent

Case Study 8.3 illustrates the importance of reacting appropriately to the results of nursing observations:

• the combination of carbamazepine and diazepam produced a prolonged period of sedation

• the patient’s initial aggression overshadowed the later fall in the consciousness level

• the nursing observations were not acted on with sufficient urgency

• the falling GCS and the increasing respiratory rate should have alerted the doctors of the impending need for ventilation. These patients are better nursed on the HDU

Case Study 8.3

A 20-year-old man with financial problems lost his job and on an impulse, took 30 of his father’s carbamazepine tablets (a total of 12g), without any alcohol.

On arrival in AED at 01.30h, he was agitated and very aggressive and refused oral charcoal. He was given 15mg of rectal diazepam and admitted.

At 03.00h his GCS was noted to be 3/15. He remained on the medical ward.

By 04.30h he became aggressive again and was given a further dose of 10mg diazepam.

He had improved by 09.30h, but deteriorated again by 21.15h the following evening:

• oxygen saturations 80%

• low pO2 (8.0kPa)

• pulse 120 beats/min

He was given high-flow oxygen and observed.

By 05.00h, his GCS had fallen to 7/15. Oxygen saturations were 86% on high-flow oxygen. His respiratory rate was 20 breaths/min.

Over the next 3h, his GCS dropped to 6/15. His respiratory rate increased to 50 breaths/min and his pulse to 120 beats/min. He was deemed unable to protect his airway and transferred to ITU for ventilation. X-ray showed aspiration pneumonia.

After 4 days on a ventilator he made a full recovery.

Case Study 8.4 shows that assessment has to be performed with care, if necessary by conforming to a checklist of high-risk factors. However, a checklist cannot replace sympathetic listening. Furthermore, simply asking if the patient ‘feels suicidal’ is often enough to identify risk. When time is at a premium, there are two key questions that are known to be an accurate prediction of genuine depression:

Case Study 8.4

A 49-year-old woman was admitted to hospital with a significant overdose of amitriptyline. She had left a suicide note to her son and had only been found at home by luck. She made a good recovery and did not appear depressed on the ward. However, on further questioning she admitted that, 2 weeks before admission, she had taken 30 nitrazepam tablets but had not told anyone about it and her husband had not been aware of her depression.

She was considered at high suicidal risk and admitted as an informal patient for further psychiatric assessment.

During the past month, have you often been bothered by:

1. Feeling down/depressed or hopeless?

2. Having little interest or pleasure in doing things?

The Patient Who Refuses Treatment

This is one of the most difficult areas of clinical practice, even for the most experienced medical and nursing staff. There are a number of common scenarios:

• a patient is admitted from casualty, but refuses to stay on the ward

• a recovering patient refuses to wait to see a psychiatrist

• a patient absconds from the ward

• a patient is intoxicated and abusive and refuses to cooperate

• a patient is cooperative, but will not see a psychiatrist

• a patient refuses specific medical treatment for the overdose

• a patient with acute alcohol withdrawal discharges himself

In all such cases, a balance must be struck between the duty of care that we owe to our patients, and a respect for their autonomy, which is based on their competence at the time to make a decision.

Within the decision-making process, there are two components to this competency:

• understanding and retaining the details of proposed treatment – its benefits, its risks and the consequences of turning it down

• having the ability to weigh up the alternatives in coming to a decision

It is important to understand that it is the ability of the patient to participate in the decision-making process, and not the quality of the decision, that is important. A competent patient can refuse treatment even if the decision seems irrational or abnormal or lacking common sense and perhaps may even result in his death.

An assessment of competency (or ‘capacity’, as it is termed legally) will, in difficult cases, require the expertise of senior medical staff, although it is clear that in most acute situations the combination of emotional distress and the effects of drugs or alcohol makes it fairly obvious when a patient is not competent to make such important decisions. The patient’s capacity must be carefully documented in the records.

If the patient is not competent to make a decision about treatment and the treatment would ‘save life and limb’ (e.g. i.v. N-acetylcysteine [Parvolex®] in severe paracetamol poisoning), then such measures can be given against the patient’s wishes under what is termed, in England and Wales, Common Law.

The Mental Health Act can be used on medical wards to detain and, in some situations, treat a patient against his wishes. However, this would only apply in exceptional circumstances: the laws are complex, they rely on careful psychiatric assessment and the laws themselves vary within the UK. In England and Wales, Section 5(2) of the Mental Health Act (1983) can be invoked to detain a medical inpatient against their will for an emergency period of 72h. Certain criteria must be met:

• The capacity to make a decision should be impaired because of a psychiatric disorder

• In the case of an overdose, the law allows life-saving treatment to be administered against the patient’s wishes if the act of deliberate self-harm was itself a direct consequence of a psychiatric disorder

• The Mental Health Act can also be used to detain a patient with a mental disorder against his will if he is a danger to himself or to others

Using the Mental Health Act is not ideal: it takes time and organisation and, for an emergency Section on the medical ward, the consultant physician has to be there in person. By their nature, these acute problems arise at extremely unsocial hours – usually at 02.00 or 03.00h.

The skill in dealing with such patients is to try and avoid the situation from arising by:

• avoiding confrontation

• maintaining a supportive and non-judgemental approach

• establishing a good relationship with the patient

• using persuasion and negotiation rather than coercion or bullying

• avoiding predictions of the time when a drip comes down/when a psychiatrist visits/of discharge

• involving the relatives, within the confines of patient confidentiality

In difficult situations, these principles should be followed:

• act reasonably and in the best interest of the patient

• involve senior nursing and medical staff at an early stage

• give the patient options should they change their mind

• use common sense

If a patient absconds or discharges themself, it is important to consider who needs to be informed and when would be the most appropriate time to do it:

• the next of kin

• the GP

• social services

• community psychiatric services

• the health visitor (if children are involved)

• the police

• the probation officer

Case Studies 8.5 and 8.6 illustrate the kinds of difficulties that may occur in cases of self-harm.

Case Study 8.5

A 25-year-old known heroin user was admitted to hospital with an overdose of diazepam and slashed wrists, soon after leaving prison. He was described by the police as a violent man and had struck his wife because of suspicion that she had been unfaithful. On admission, he was conscious, but had slurred speech and was drowsy.

Soon after admission, in the middle of the night, he walked out of the ward taking his drip and drip stand with him, to stay with his friends near the hospital.The police were informed and persuaded him to return. By 03.00h he was threatening to walk out again, saying that he was going to kill himself.

What were the options?

• Let him go again. He exhibited several high-risk features for suicide: substance abuse, male, etc.

• Detain him under common law. He is under the influence of the diazepam overdose and is probably not competent to make decisions. He is a danger to himself.

• Section 5(2) of the Mental Health Act.There is no mental illness immediately obvious.

• Persuasion. After a long talk with a senior doctor, he calmed down. It transpired he was virtually illiterate, was depressed about his hopeless employment prospects, and had been denied access to his children because of his behaviour. His marriage looked unlikely to survive the effect of his prison sentence. He was referred for some form of problem-solving based therapy.

• Negotiation. Typically for this type of situation, the problem of smoking on the ward became a major issue. Agreeing to let the patient find an acceptable place to smoke can defuse tension and also form the basis of negotiation to try and encourage the patient to stay on a voluntary basis.

Case Study 8.6

A 40-year-old man was admitted to hospital having taken a trivial amount of nitrazepam. He had cut his left arm (to ‘let out the badness’). He was hearing voices that were telling him to kill himself, and he was demanding to leave hospital. He was pacing the room and wringing his hands in agitation, saying he just wanted to be left in peace to go home and die.

He had previously had ECT and had been on various psychotropic drugs.

In the early hours he continued in his efforts to leave the ward, and there were practical problems in obtaining psychiatric help.The security staff were called and the consultant physician came in. After evaluating the situation, the consultant signed Form 12 (Section 5(2)) which, after being received by the manager of the mental health services, detained the patient against his will for 72h to allow a psychiatric assessment to be made. A mental health nurse was seconded to look after the patient until the morning, when he was transferred to the mental health unit.

Specific Overdoses

Three type of drugs make up 85% of the overdoses: of these, paracetamol and antidepressants are particularly toxic.

| • Paracetamol | 45% |

| • Benzodiazepines | 20% |

| • Antidepressants | 20% |

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines, unless taken as part of a more toxic cocktail, depress the consciousness level, but not sufficiently to put respiration at risk unless the patient also aspirates. Management is based on maintaining respiration and keeping a secure airway. The specific antagonist i.v. flumazenil reverses benzodiazepine coma immediately, but the drug has potential problems:

• the effects of a single dose soon wear off

• if tricyclic antidepressants may also have been taken, flumazenil is contraindicated: the surge in excitability associated with sudden benzodiazepine reversal may trigger a life-threatening tricyclic-induced cardiac arrhythmia

• the sudden reversal of benzodiazepine coma may trigger acute agitation – this will need careful management

Paracetamol Poisoning

Paracetamol poisoning is common and dangerous. There are 70 000 cases per year in the UK, and of these 200 will die due to liver damage – paracetamol remains the most common cause of acute liver failure.

How does it cause liver damage?

In overdosage, the first pathway is swamped and large quantities of paracetamol are sent down the p450 route to produce NAPQI. Glutathione stores are eventually exhausted in mopping up excessive NAPQI. Once this happens, NAPQI starts to destroy the liver.

These simple biochemical pathways explain three important facts:

• chronic alcoholics and malnourished patients have low glutathione levels and are therefore particularly susceptible to paracetamol toxicity

• N-acetylcysteine (Parvolex®) and methionine, which replenish glutathione stores, will act as effective antidotes in paracetamol poisoning

• drugs that increase p450 levels (anticonvulsant therapy, anti-TB treatment, St John’s Wort) send more of the paracetamol down the ‘toxic route’ and increase the toxicity of paracetamol

How much is a significant overdose?

For most patients 12g of paracetamol (24 tablets) or more than 150mg per kg body weight can produce severe liver damage.

• In susceptible patients – the malnourished (especially patients with HIV, cystic fibrosis and eating disorders) or alcoholics – half of this amount can be dangerous

• Liver toxicity may occur even if the tablets are ingested over the course of several hours

• You cannot rely on the patient’s story for the quantity or the timing of the overdose

• Patients will often have taken combination tablets (e.g. dextropropoxyphene and paracetamol) or a cocktail of drugs and alcohol that may each need treatment in their own right

Clinical picture of severe paracetamol toxicity

0–24h

• Minimal immediate symptoms

• Mild nausea and vomiting within a few hours

• Liver function tests normal in the first 12h, abnormal by 18h

24–48h

• Right upper abdominal pain with continued vomiting

• Liver tenderness

• Progressively deranged liver function tests (ALT and AST levels > 1000IU/L indicate severe damage)

• Prolonged prothrombin time

• Loin pain, haematuria, proteinuria and deteriorating kidney function

Immediate management

• It is critical to establish the exact timing of the overdose. Focus on the history:

— time tablets purchased

— time tablets swallowed

— time help arrived

— could the overdose have been staggered over several hours?

• What else was taken? Co-proxamol (325mg paracetamol and dextropropoxyphene) is frequently taken in self-poisoning. Dextropropoxyphene is an opioid and, especially when mixed with alcohol, can cause sudden and severe respiratory depression with coma, pinpoint pupils and cardiovascular collapse. Coma management and reversal of the drug’s effect with naloxone is the immediate priority: patients may subsequently develop liver damage from the paracetamol

• Is this a susceptible patient?

— eating disorder, HIV, cystic fibrosis or malnourished

— chronic alcoholic

— epileptic medication/anti-TB drugs

— underweight (toxic dose (150mg/kg) in a 50-kg patient is 15 tablets)

• Consider activated charcoal

— overdose taken within an hour

— methionine is not going to be used (charcoal inactivates methionine)

• Take blood for measurement of paracetamol levels (if overdose taken within an hour or so of admission, wait 4h before testing, but if more than 24 tablets taken, still consider immediate antidote). Determine baseline LFTs and clotting, particularly if a substantial overdose or of uncertain timing

• Start N-acetylcysteine (Parvolex®) treatment if indicated. Repeat LFTs and prothrombin time at the end of the infusion (20h).

Late presentation (8–24h) or staggered ingestion over several hours

The situation is urgent, because any delay progressively reduces the effectiveness of N-acetylcysteine (Parvolex®) and patients who present late tend to have more serious overdoses. If more than 150mg/kg or 12g have been taken, it is safest to start treatment while awaiting the blood results. The following factors are considered:

• history (toxic dose of > 150mg/kg per day)

• symptoms (abdominal pain and vomiting)

• blood levels (of little value in staggered overdoses)

• liver function tests and creatinine

• blood gases

The use of N-acetylcysteine (Parvolex®) at times in excess of 24h is uncertain, but it should be given if the prothrombin time, creatinine or liver enzymes are abnormal or if the blood gases show an acidosis.

Who gets i.v. N-acetylcysteine (Parvolex®) or methionine?

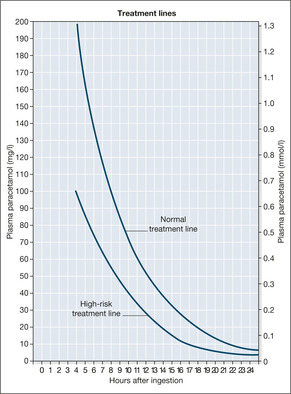

A single paracetamol blood level measured at 4h or more after the overdose will predict who is at risk from liver damage. Blood levels from earlier than 4h are of no value in assessing the risk of liver damage. The graph of the blood levels of paracetamol against time since the overdose is used to determine who needs the antidote (→Fig. 8.1). The timing of the overdose is therefore critical to the management of the patient. Patients with a paracetamol value that falls above the ‘normal treatment line’ joining 200mg/L at 4h to 6.25mg/L at 24h have a 60% chance of serious liver damage that N-acetylcysteine (Parvolex®) or methionine will completely prevent.

The second ‘high-risk treatment line’ on the graph joining lower levels is used in patients who are particularly susceptible because of malnourishment etc.

• The graphs only apply for tablets taken as a single dose: overdoses stretching over hours or days are difficult to evaluate using blood levels

• When in any doubt – TREAT AND TREAT WITHOUT DELAY!

N-acetylcysteine (Parvolex®) and methionine are most effective if given within 12h of the overdose, but Parvolex® works up to 24h and possibly longer. It is the treatment of choice on the Acute Medical Unit, but methionine is useful in particular situations:

• the patient refuses a drip

• the patient insists on leaving hospital, but would take methionine with him

N-acetylcysteine (Parvolex®). The patient must be weighed, so that the correct dose can be given:

• 150mg/kg in 200ml of 5% dextrose over 15min

• 50mg/kg in 500ml of 5% dextrose over 4h

• 100mg/kg in 1000ml of 5% dextrose over 16h

Double-check that the correct dose of N-acetylcysteine (Parvolex®) is drawn up: 1ml contains 200mg of Parvolex® – 1 ampoule contains 2000mg

In cases of severe overdosage the infusion will be used beyond 24h (at a rate of 150mg/kg per 24h) until the prothrombin time decreases to less than 20s. If there is severe liver damage, the patient must be kept very well hydrated and broad-spectrum antibiotics such as i.v. cefuroxime given.

When to discharge

Patients should be discharged only:

• after psychosocial assessment

• after completion of N-acetylcysteine (Parvolex®), provided that the liver enzymes, creatinine and prothrombin time are normal

• and if there are no symptoms

There is a poor prognosis 24h after the overdose, and a Liver Unit must be consulted, if:

• prothrombin time is more than 75s

• pH < 7.3

• creatinine is > 300μmol/L

• arterial lactate > 3–3.5mmol/L

• hepatic encephalopathy (grade III-IV)

Clear instructions, as outlined in Box 8.2, should be given to the patient who discharges themself.

Box 8.2

• Return if there is:

— abdominal pain

— persistent vomiting

— confusion

• Consider oral methionine

Antidepressant Overdose

There are two important types of antidepressants used in deliberate self-harm:

• The older tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. dothiepin, amitriptyline, protriptyline)

— these are dangerous and cause coma, convulsions and cardiac arrhythmias

— dothiepin is the most dangerous, particularly as it is available in 75mg tablet strength

• The new generation of antidepressants (SSRIs)

— drugs like fluoxitine, while safer than tricyclics, can cause ‘serotonin syndrome’ – acute confusion, fever, muscular rigidity and twitching

Management

The tricyclic overdose provides the classic example of patients who ‘were fine’ in the AED but then deteriorated at a frightening rate when they reached the ward – often doing so in the critical interval between the initial nursing assessment and when they were seen by the junior doctor.

The main dangers are:

• Respiratory depression. The GCS, respiratory rate and oxygen saturations should be monitored hourly in these patients, more often if they are showing any signs of toxicity. Blood gases are checked: tricyclic poisoning can cause a dangerous acidosis that needs correction with i.v. sodium bicarbonate.

• Cardiac arrhythmias. Patients must be monitored and cared for near the nursing station. The first sign of trouble may be a cardiac arrest in ventricular fibrillation. A standard ECG recording may show warning signs of cardiac toxicity (the QRS complexes are slurred to more than the width of four small squares). Arrhythmias can be abolished with i.v. sodium bicarbonate which can be given prophylactically if there are warning ECG changes – conventional antiarrhythmic drugs can make the situation worse by depressing cardiac function.

• Convulsions. These are treated with i.v. diazepam or lorazepam.

Patients remain at risk for at least 12h after admission and are prone to arrhythmias if they mobilise prematurely. Dothiepin, in particular, has been associated with a significant number of in-hospital deaths.

Immediate management of tricyclic overdose

Gastric lavage?

There is little point in lavage unless large amounts of the drug have been taken within the hour. Indeed, by pushing the tablets further down the gut, lavage may increase absorption.

Single-dose activated charcoal

A single dose of 50g of activated charcoal reduces absorption if given within an hour of ingestion. If there are signs of significant drug toxicity, a further dose can be given at 2h.

Carbon Monoxide Poisoning

Basic mechanisms

Carbon monoxide is odourless, colourless and extremely dangerous. It binds to and poisons circulating haemoglobin, preventing it from taking up, or releasing, oxygen. As a consequence, patients suffer hypoxic damage to the heart and central nervous system.

Clinical picture

Acute exposure

Headache, nausea and dizziness progressing to collapse and loss of consciousness. In severe poisoning with coma, there may be skin blistering and pressure-induced muscle damage (rhabdomyolysis). The limbs are spastic and there may be acute heart damage, pulmonary oedema or increased intracranial pressure.

Subacute exposure

Slower onset of nausea, vomiting, headaches and drowsiness. The clinical picture can mimic flu or gastroenteritis – a source of confusion. As with gastroenteritis, a whole household can be affected if exposed to the same source.

Assessment and management

• ABCDE: care of the patient with an impaired consciousness level:

— airway management

— assess cardiac function, monitor the heart rhythm, measure Troponins

— monitor oxygen saturations

— monitor blood gases and venous blood for COHb levels. Severe toxicity is associated with COHb levels greater than 20% (heavy smokers reach levels of 8–10%)

• Give immediate high-concentration oxygen – 100% oxygen is indicated for significant toxicity. This will need to be delivered via a tightly fitting mask with an inflated face-seal (seek anaesthetists’ advice, as the standard non-re-breathing masks are inadequate)

• Consider hyperbaric oxygen (oxygen given in a specialist unit at 2.4 times normal atmospheric pressure), especially in cases of:

— pregnancy

— COHb more than 20%

— signs of neurological dysfunction

• If it is accidental domestic exposure, the local environmental health department should be involved to assess the safety of the house

Alcohol Abuse

Problems of Alcohol on the Acute Medical Unit

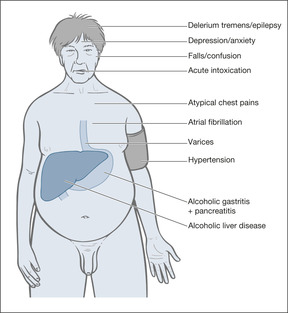

Estimates suggest that around 20% of acute medical admissions are directly or indirectly the result of alcohol abuse (→Fig. 8.2). Acute alcohol intoxication is potentially dangerous in terms of respiratory depression and aspiration, and must be managed carefully. It is equally important to recognise chronic alcohol dependence – those patients who, while they would not necessarily concede to being ‘alcoholic’, have drinking patterns that cause repeated problems to themselves and others.

• Acute alcohol intoxication – common in young adults

• Alcohol as a component of deliberate self-harm – alcohol and paracetamol or antidepressants/benzodiazepines are commonly taken in combination. The risks are of respiratory depression and aspiration. The associated intoxication makes history-taking difficult and often results in a very uncooperative patient

• Alcohol dependence as a cause of deliberate self-harm – either in the patient or in his close family/partner

• Alcohol-induced disease:

— alcoholic gastritis

— acute variceal bleeding

— alcoholic liver disease

— pancreatitis

• Other alcohol-associated medical conditions:

— unexplained vomiting

— atypical chest pain (often after binges)

— binge-associated acute atrial fibrillation

— hypertension

— unexplained falls and confusion in the elderly

— depression

How to take a drinking history

Although patients with alcohol-related problems do not usually welcome detailed enquiries into their drinking habits, an acute drink-related crisis in their health or personal life is often followed by a period of reflection and self-examination. During this time the patient may accept for the first time that alcohol may be the root cause of his problem.

It is surprising how often the bland question ‘Do you think you may have been burning the candle at both ends?’ leads to important disclosures and an initial acknowledgement of the critical issue.

It is important to establish the levels of consumption and of dependence.

The amount and pattern of drinking

1. How often do you drink (include ‘stiffeners’ added, particularly by the elderly, to tea and coffee)?

2. How much do you drink on a usual day (a unit is half a pint, a glass of wine or a single measure of spirits)? A regular consumption of more than 4 units a day puts the patient ‘at risk’.

3. Have you had more than 5 units any day in the past month?

4. Have you had home, health or work problems in the last year due to drink?

5. Has anyone (including yourself) been harmed by your drinking?

6. Do you use alcohol to help solve your problems?

7. Has anyone suggested that you cut down?

The level of dependence

1. Do you have difficulty in controlling the amount that you drink once you start?

2. Do you have difficulty cutting down?

3. Do you have withdrawal symptoms (including early awakening and episodic anxiety)?

4. Are you drinking to avoid withdrawal symptoms?

These questions are distilled into a shortened form: the CAGE questionnaire. Two or more positive answers to the four questions suggests alcohol dependence.

• Have you been Annoyed by criticism of your drinking?

• Have you felt Guilty about your drinking?

• Do you ever have an Eye-opener in the morning to steady your nerves?

CAGE can be used on the patient to confirm any suspicions of alcohol dependence raised from an initial drinking history. The nature of the questions, however, means that it is not good for identifying problems in young adults or in the elderly.

Acute alcohol-withdrawal syndrome

Case Studies 8.7 highlight some features of acute alcohol-withdrawal syndrome.

• It is important to recognise the clinical features of alcohol withdrawal in any patient admitted to hospital (→Box 8.3). Timely sedation with benzodiazepines will prevent the onset of convulsions or progression to delirium tremens. The most effective regimen is to control the agitation, sweating and tremor with ‘symptom-triggered dosing’ using oral diazepam 10–20mg every 2h up to a maximum of 100mg in 24h. Antiemetics may also be required.

Box 8.3

• Tremor

• Sweating

• Apprehension

• Nausea and vomiting

• Weakness and syncope

• Insomnia

• Auditory and visual hallucinations

• Fitting

• Severe confusion

• Patients with alcohol-withdrawal syndrome are often very apprehensive or frightened. They may be acutely disturbed and hallucinating. It is important to nurse them in a well-lit room and provide a calm, reassuring environment.

• Severe acute alcoholic agitation can be managed with i.v. diazepam 5–10mg over 2min. An infusion of chlormethiazole (Heminevrin®) is the traditional treatment for acute withdrawal states, but it carries a risk of respiratory depression. When taken long-term, chlormethiazole can itself lead to dependence and has in general been replaced by the benzodiazepines.

• If the patient looks poorly nourished or is confused and unsteady on his feet, an acute Wernicke Korsakoff Syndrome (WKS) may be developing. WKS is a serious acute brain disturbance caused by thiamine deficiency and can be triggered in hospital by a carbohydrate load such as an infusion of dextrose. The clinical picture can be confused with that of acute intoxication, but the damage is permanent unless treated urgently with i.v. thiamine (in the form of high-dose vitamins B and C combination (Pabrinex®): two pairs of ampoules three times a day for 3–5 days, each pair infused in 100ml of normal saline over 30min).

Case Studies 8.7

CASE 1

A 35-year-old man was admitted, having had a grand mal fit. He had discharged himself from AED a week before after a similar episode. He had been drinking cider heavily for 15 years, and since losing his father 6 months previously he had been drinking up to two bottles of vodka per day and had started antidepressants. He had recently had a normal endoscopy and colonoscopy for morning vomiting and episodic diarrhoea. On examination, he had severe shaking and sweating and was extremely agitated and anxious.

His liver enzymes were high and his alcohol levels were zero. His MCV was 103μm3. He was started on a regimen of chlordiazepoxide and high-dose parenteral vitamins.Within 36h he was much improved, but insisted on discharging himself, with a promise that he would stop drinking ‘through his own efforts’. He continued on a reducing regimen of chlordiazepoxide.

CASE 2

A 40-year-old man was admitted to hospital after a series of grand mal convulsions. He was a club steward on holiday in the area.While working, he would drink ‘constantly’ throughout the day and evening, but would always stop completely on holiday. He was treated with thiamine and a benzodiazepine withdrawal regimen, and made a full recovery.

Acute alcohol intoxication

• There is an increasing problem with young people binge-drinking out of doors, encouraged by the ready availability of ‘designer drinks’, including types of fortified wines and strong white ciders (→Case Study 8.8)

Case Study 8.8

A 16-year-old boy was admitted with a GCS of 3 and an unrecordable blood sugar, having been found lying in an outdoor play area. He had been drinking white cider and vodka out of doors with his friends. He recovered uneventfully over a period of 12h, with attention to his airway and correction of his blood sugar.

• The main problems are hypoglycaemia, respiratory depression, airway protection and, in severe cases, fitting

• The units of measurement are confusing and can lead to misinterpretation:

— UK driving limit 16mmol/L (80mg/100ml)

— Severe intoxication 76–98mmol/L (350–450mg/100ml)

— Potentially fatal > 98mmol/L (> 450mg/100ml)

The management is that of any metabolic coma, with a number of important exceptions:

• Alcoholics are prone to head injuries while intoxicated:

— take a history from any witnesses

— observe carefully for signs of trauma (bruising behind the ears, boggy swelling, etc.)

— monitor the GCS – it is not appropriate to assume the patient will simply ‘sleep it off’

— failure to recover fully after a head injury may indicate impending WKS

• Acocktail of drugs and alcohol may have been taken – a situation that is particularly dangerous in opiate abusers

• In severe intoxication, start i.v. dextrose 10% 250ml. If i.v. dextrose is being used in a chronic alcohol abuser, combine it with thiamine to avoid triggering the WKS. The management of severe intoxication in the familiar ‘hardened’ drinker who is unkempt and malnourished (and often disruptive) should include at least one pair of thiamine and vitamin C (Pabrinex®) ampoules daily for the first 3 days.

Alcohol, dextropropoxyphene and opiates

The combination of dextropropoxyphene-containing tablets such as coproxamol with alcohol can, in overdosage, be a particularly potent cause of severe respiratory depression. A similar situation occurs with methadone and alcohol. The interactions are unpredictable and, because all these drugs induce vomiting, these patients are also at particular risk from aspiration. Intravenous naloxone reverses the depressed conscious level, but single doses wear off within a short time, so the conscious level needs to be monitored regularly.

Ethylene Glycol and Methanol: Antifreeze and Windscreen Washer Solution

Ethylene glycol and methanol can be ingested in error, as a deliberate act or, misguidedly, for recreational purposes. Both substances cause a profound acidosis, acute multi-organ damage and, in the case of methanol, permanent blindness, and are extremely dangerous. The clinical picture can mimic diabetic ketoacidosis and the diagnosis may be overlooked. The intravenous drug Fomepizole® inhibits the liver enzyme which converts the two substances into highly toxic by-products (ethylene into oxalic acid and methanol into formic acid). Fomepizole® is a highly effective antidote if given early.

Substance Abuse

Cocaine

Cocaine imparts its desired effects by stimulating the release of the stress hormones, noradrenaline (norepinephrine), adrenaline (epinephrine) and dopamine to inappropriately high levels. The effects are dramatic, as may be the side-effects – notably stroke, heart attack and aortic dissection. Cocaine is a major cause of drug-related death and any young fit adult admitted with unexplained cardiovascular or cerebro-vascular emergencies should be asked about cocaine use (the maximum risk is within the first hour of a dose). The nature of the cardiac damage includes cocaine-related chest pain, Acute Coronary Syndrome, acute myocardial infarction, acute arrhythmias and, with prolonged use, cocaine induced heart muscle damage. The sudden changes in pulse rate and blood pressure can trigger cerebral infarction, cerebral haemorrhage and can tear major blood vessels (aortic and coronary artery dissection).

Treatment of all of these complications should follow conventional lines except that beta-blockers are contra-indicated and that high-dose benzodiazepines may be needed to reduce cocaine-induced agitation.

Ecstasy

Ecstasy, or MDMA, has been a commonly used recreational drug for the past decade, particularly in the clubbing scene. Its amphetamine-like properties provide hyperstimulation, which, combined with the exertion of prolonged dancing, can result in:

• dehydration and electrolyte disturbance

• hyperarousal – agitation, tachycardia, hypertension

• muscle breakdown (rhabdomyolysis) and kidney failure

• hyperthermia up to 40°C

• convulsions

• acute liver failure

• severe acidosis

Management

Reassurance and adequate i.v. fluids are the main measures. Hyperthermia is managed by active cooling and with i.v. dantrolene 1mg/kg repeated as needed, to a maximum of 10mg/kg. Acute agitation and convulsions respond to benzodiazepines. Acidosis may need correction with sodium bicarbonate.

Liquid Ecstasy

Liquid ecstasy is the drug GHB. Case Study 8.9 illustrates abuse of this substance.

Case Study 8.9

Two women aged 24 and 21 years who were at a night club each took four bottle-capfuls of a pink aniseed-flavoured liquid that they knew to be GHB. Within a few minutes they developed euphoria that progressed over an hour to drowsiness and coma.They were carried out by bouncers and the paramedics were called.

On admission:

| Case one | Case two | |

|---|---|---|

| GCS | E1 V1 M1 | E2 V2 M1 |

| Pulse | 30 | 42 |

| Blood pressure | Unrecordable | 70/40 |

| Respiratory rate | 6 | 8 |

| Pupils | Normal and reactive | Pinpoint |

| Treatment | Atropine Charcoal | Atropine Charcoal |

The anaesthetists were called and oropharyngeal/nasopharyngeal airways were passed. Activated charcoal was administered down a nasogastric tube. Atropine 1mg increased the pulse and blood pressures and both patients regained consciousness within 3–4h. According to the women, the desired effect is usually generalised tingling and a floating euphoria.This was the first time they had not spread the doses over 3 or 4 hours.

Dystonic Reaction and Psychotropic Drugs

Case Study 8.10 describes abuse of psychotropic drugs. The picture is typical of the abnormal posture and muscle spasms that occur in acute dystonic reactions to a variety of psychotropic drugs, including haloperidol, and various antiemetics, including metoclopramide. Problems with substance abuse are widespread in the prison population.

Case Study 8.10

A prisoner with a previous history of psychosis and i.v. amphetamine abuse found a packet of tablets in a copy of a novel in the prison library. He took them for a buzz. A few minutes after taking them, he developed what he thought was a fit, with intense spasm of his jaw and neck and arching of his back.

He was taken to casualty, and after an intramuscular injection of procyclidine 10mg his symptoms improved rapidly.

Heroin Abuse

Heroin abuse is an increasing problem, particularly among the young, and is associated with several major health-related and psychosocial problems (→Case Study 8.11):

• HIV

• hepatitis C and B

• superficial and deep soft tissue sepsis

• venous thromboembolic disease

• opiate overdose (often combined with temazepam, alcohol and diazepam)

• social isolation

• crime

Case Study 8.11

A 17-year-old single girl was admitted with acute asthma because her inhalers had run out. She had been smoking heroin for 2 years but in the last month her boyfriend, who was now in prison, had introduced her to intravenous heroin. She was using 1g a day, which she funded by shoplifting. She had been thrown out by her mother and did not get on with her father. She wanted to sort out her life and her asthma.

Methods of heroin ingestion

Chasing the dragon. An increasingly popular way of taking heroin, ‘chasers’ are younger, show less dependence and are less involved in the heroin culture than the more traditional i.v. user. Heroin is heated on tin foil and inhaled. Alternatively, it is smoked as a cigarette – ‘tooting’.

Mainlining. In contrast to chasers, injectors are older and more likely to be male. They show high dependence and are likely to be using the drug in higher doses and on a daily basis. They are unlikely to have non-users as friends, and are steeped in heroin ‘culture’. This group is increasingly turning to methadone treatment programmes.

Many established users will have been injecting opiates for years: the average age at a methadone maintenance clinic will be around 35 years, with most starting to inject opiates at around the age of 20 years. More than 70% of these long-term addicts will test positive for the hepatitis C virus, around 50% will be positive for hepatitis B, and a significant proportion will be HIV positive. At least half will have shared injection apparatus.

Heroin overdose

Overdose may be due to simple error (especially if alcohol is also involved), to inadvertent ingestion of a particularly pure batch of heroin, to loss of tolerance following abstinence or to a deliberate act of self-harm. Patients are usually deeply comatose, with pin-point pupils. Treatment is with i.v. naloxone, the specific antidote, but reversal can be dramatic, leading to acute agitation, aggression and violence.

Methadone therapy

Addicts who are admitted to medical wards often claim that they are ‘registered’ and as such they are ‘entitled’ to methadone or even to diamorphine.

• Only doctors who hold a special Home Office licence may prescribe diamorphine for the treatment of drug addiction.

• Since 1997, addicts are no longer registered with the Home Office (although there are voluntary anonymised regional and national Drug Misuse Databases for patients who first present with drug misuse).

• The addict will demand methadone in hospital because he realises that he is dealing with inexperienced staff who may comply with his wishes.

• Methadone can be abused and has a high value on the black market, particularly in tablet form (which can be crushed and injected) and in ampoules.

• The current recommendations for a methadone treatment programme are:

— only methadone syrup, not tablets, should be prescribed

— daily prescriptions should be given

— the effective maintenance dose should not exceed 50–100mg of methadone daily

Methadone programmes are carefully supervised and managed with a system of daily supply and directly observed ingestion. Apart from using methadone syrup (not tablets or injectable forms), effective treatment programmes monitor drug ingestion with blood and urine testing (the prevailing ethos for treating drug addiction is one of ‘tough love’).

Methadone treatment is not universally popular and some institutions, notably the prison service, use dihydrocodeine, in long-acting preparations, to aid withdrawal. Buprenorphine is a useful alternative heroin substitute, particularly as it has a low risk of causing respiratory depression if taken in excess. A typical regimen would be a rapidly tapering course of sublingual buprenorphine, starting at 4–16mg per day, to be followed up longer term by the opiate blocker, naltrexone.

Nursing assessment of the addict

• What drugs: how and in what quantity?

• Is the patient known to the Drugs Advisory Service?

• Is there a child at risk or is the patient pregnant?

Infections in Intravenous Drug Users (IVDU)

Intravenous drug users are at risk from severe infections: they use contaminated equipment and drugs, clean injection techniques are the exception and their levels of immunity are low, not necessarily by HIV infection, often simply due to poor social circumstances and self-neglect. Typical clinical pictures include:

Skin and injection sites: Cellulitis, abscesses and necrotising fasciitis Systemic infection: Sepsis and toxic shock syndrome

Respiratory tract: Pneumonia and empyema, infected pulmonary emboli

Musculoskeletal: Joint infections (sterno-clavicular, pelvis, spine and large joints)

Cardiac: Endocarditis of the tricuspid valve

Several unusual outbreaks have been caused by specific drug-related problems: botulism due to contaminated black tar heroin from Mexico, tetanus from heroin infected with Clostridium tetani and, most recently, anthrax from contaminated heroin in Scotland. It is therefore important to be vigilant for clusters of unusual infections among the IVDU population. Those with anthrax, for example, showed specific severe soft tissue infection which progressed rapidly to necrotising fasciitis and overwhelming sepsis – others presented with an apparent subarachnoid bleed which was actually the result of the haemorrhagic meningitis which is a feature of anthrax.

Special Risks to Members of Staff

Needle Stick Injuries

HIV, HBV and HCV are blood-borne infections that put at risk those nurses who are exposed to the blood of infected patients.

The nature of the risk

A needle stick injury with HIV-infected blood carries a small but significant risk (1 in 300) of HIV infection in the recipient. Hepatitis is more easily transmitted than HIV: if the blood is from a patient with hepatitis, the risk can be as high as 1 in 10. The risks are lower after exposure of broken skin (e.g. severe eczema on a nurse’s hands) or mucous membranes (eyes or mouth) to infected blood or blood-stained body fluids.

Nurses must be aware of the risks and systems of care should assume that blood-borne infection could be present in any or every patient. There must be a well-publicised local policy from Occupational Health, consistent with the most recent Department of Health Guidelines.

It is vital that staff know what to do in the event of a needle stick injury:

• Who do you contact during the day?

• Who do you contact at night and at weekends?

• Where are the starter packs for HIV prophylaxis?

• Could the system deliver HIV prophylaxis within 1h of the incident?

• What blood specimens need to be taken from the patient and the staff member?

• Who can give expert advice?

Outcome

The outcome of the incident depends on four factors:

• type of exposure

• status of patient (HBV positive/HBC positive/HIV positive)

• immunity of staff member (hepatitis B immunisation)

• effectiveness and timeliness of the emergency measures

What constitutes significant exposure?

• Needle stick or blood-contaminated sharps

• Bite causing skin puncture

• Mucocutaneous exposure to blood or blood-stained body fluids

What emergency action should be taken?

The important emergency interventions are the immediate (ideally within 1h) institution of triple-drug antiretroviral therapy in a definite HIV exposure, and instituting accelerated anti-hepatitis B vaccination or a booster dose of vaccine in the case of definite exposure to hepatitis B.

Risk assessment to identify the patient’s infectivity

1. Hepatitis B (positive for hepatitis B surface and E antigens: HBsAg, HBeAg)

2. Hepatitis C

3. HIV positive

4. Known to have HIV risk factors

Blood testing of patient and storage of blood from staff member. If there has been significant exposure, the patient should have his HbsAg checked urgently. If there are risk factors for hepatitis C or HIV, consent should also be sought to check these. The possible outcomes are therefore:

1. urgent testing of the patient (10ml blood for HBsAg, HVC, HIV and storage)

2. storage with delayed testing should it be necessary

3. baseline tests on the nurse and storage for later testing

Documentation

Document the incident using an official incident form.

Hospital-Acquired Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Infections

Hospital acquired MRSA is an increasing problem leading to unnecessary deaths and disability. Healthcare workers infect themselves by handling MRSA-positive patients and from touching adjacent contaminated surfaces. The staff then spread the organism from one patient to another. Spread is prevented by effective isolation, careful room cleaning and the use of universal precautions, of which by far the most important is thorough and frequent hand-washing.

Violent Incidents

The most common forms of violence on the acute medical wards are those seen in severely agitated patients with confusional states who strike out, grab or scratch the medical or nursing staff, whom they misinterpret as posing a threat. Less common, but more dangerous, is the physical aggression that accompanies severe paranoid states due to an acute physical or psychiatric illness. The combination of drug or alcohol intoxication with a paranoid illness is particularly dangerous.

The principles of management are:

• do not take risks

• any patient showing an obvious paranoid state should be asked if they are carrying any sort of weapon

• ensure your own safety and that of the patient

• seek immediate help from other staff members

• use the absolute minimum of force to control the situation

Prevention

• Recognise the causes:

— acute anxiety and fear

— alcohol and drug-withdrawal syndromes

— delirium

— dementia

— major psychosis, e.g. paranoid schizophrenia

• Recognise the warning signs:

— agitation

— shouting and pacing the room

— misinterpreting nursing interventions as personal threats

— threats of violence and previous violent behaviour

— paranoid ideas, fearing for their life

— delirium/clouded consciousness

Management

The acutely disturbed and potentially violent patient should be cared for only by an appropriate number of trained, experienced and easily identified (uniformed) staff. It is critical that a medical assessment is made at an early stage to detect reversible causes of acute confusion, e.g. hypoxia, infection, drug toxicity. The patient should be nursed in a quiet, well-lit room in which he cannot harm himself. It can be calming to an acutely disturbed patient if you exhibit a relaxed but attentive manner and avoid anything that could be misinterpreted as being confrontational. Listen, explain and reassure. Remember that any physical contact may be misinterpreted as threatening behaviour, so explain very clearly what it is you are planning to do in terms of nursing observations and monitoring. If the situation deteriorates, you must obtain immediate help from the medical and security staff and, if serious violence is threatened, e.g. with a weapon, the police.

There are situations in which common sense dictates that the patient should be restrained for their own safety: a clear example is someone with a severe toxic confusional state who has become acutely paranoid and is trying to escape through a window. Patients who are mentally disordered and putting themselves or others at risk can be treated under Common Law without consent.

To calm an acutely disturbed or aggressive patient intramuscular sedation can be used and repeated when necessary:

| Midazolam | 7.5–15mg |

| or | |

| Haloperidol | 5–10mg combined with 50mg of promethazine |

If sedation is administered, the patient must be monitored carefully to prevent aspiration, respiratory depression and hypotension.

If, as a last resort, temporary restraining force is needed, there must be a sufficient number of experienced staff to apply it to an absolute minimum, ensuring the patient comes to no harm. Under these situations, it is essential to involve senior nursing and medical staff and subsequently to complete detailed nursing documentation.

Further Reading

Hassan, T.B.; MacNamara, A.F.; Davy, A.; et al., Management of deliberate self poisoning in adults in four teaching hospitals: descriptive study, British Medical Journal 316 (1998) 831–832.

Hassan, T.B.; MacNamara, A.F.; Davy, A.; et al., Managing patients with deliberate self harm who refuse treatment in the accident and emergency department, British Medical Journal 319 (1999) 107–109.

House, A.; Owens, D.; Patchett, L., Deliberate self harm, Quality in Health Care 8 (2) (1999) 137–143.

Roberts, D.; Mackay, G., A nursing model of overdose assessment, Nursing Times 95 (3) (1999) 58–60.

UK National Poisons Information Service, National guidelines: Management of acute paracetamol poisoning. (1995) Paracetamol Information Centre in collaboration with the British Association for Accident and Emergency Medicine, London .

Web Addresses

http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/pubs/books/ActNHSai/alcoholNHSappx.pdf Guidelines for acute alcohol withdrawal: http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/pubs/books/ActNHSai/alcoholNHSappx.pdf.

NICE Guidelines for Self-Harm, http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG16 (2004).

TOXBASE TOXBASE, The UK on-line poisons information service: http://www.spib.axl.co.uk/.