CHAPTER 32 Degenerative Disease of the Metacarpophalangeal and Proximal Interphalangeal Joints

The concept of small joint arthroscopy was first delineated by Young Chang Chen, who presented a broad treatise on arthroscopy of the wrist and finger joints at a symposium that was later published in the July 1979 issue of Orthopedic Clinics of North America.1 Chen described cadaver arthroscopic anatomy and clinical cases involving the wrist, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints of the hand. The thumb trapeziometacarpal joint was not addressed. However, the smaller joint arthroscopy was described using a no. 24 Watanabe arthroscope, which was the precursor of the modern small joint arthroscope and micro-arthroscope.

The first clinical report of MCP joint arthroscopy was not published until 1985, when Vaupel and Andrews described diagnostic and operative arthroscopy of the thumb MCP joint in a professional golfer who had experienced 1 year of pain, swelling, and stiffness in his nondominant thumb.2 The technique was briefly described, and the clinical indications and results were outlined as a case report.

Arthroscopy of the proximal PIP joint had been mentioned in a cursory fashion in many case reports, beginning as early as 1997 by Richard Berger, but it was not clearly outlined until 2002, when Thomsen and colleagues described the clinical indications and arthroscopic portals in “Arthroscopy of the Proximal Interphalangeal Joints of the Finger,” published in the British Journal of Hand Surgery.3 MCP joint and PIP joint arthroscopic techniques have remained little explored by the hand surgery community, and they are virtually unknown among general orthopedic surgeons.

ANATOMY

Degenerative joint disease can be divided into post-traumatic disease, osteoarthritis, and inflammatory arthropathy, such as rheumatoid arthritis. In the MCP and PIP joints, the post-traumatic variant is most common, because these joints are frequently injured. However, rheumatoid arthritis also is a common indication, particularly in the MCP joint, which is a hallmark of rheumatoid disease in the hand. In 2002, Sisato Sekiya of Nagoya Medical School in Japan evaluated arthroscopic rheumatoid synovectomy in the PIP and MCP joints in Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery,4 but a review of degenerative joint disease in the MCP and PIP joints is lacking. This chapter outlines the indications and the operative technique for arthroscopy of these critical joints, addressing acute and chronic pathology.

METACARPOPHALANGEAL JOINT ARTHROSCOPY

Background

Chen was the first to formally describe the arthroscopic anatomy of the MCP joint1; in several case reports, he described the arthroscopic findings and their clinical relevance. He performed 90 arthroscopies in multiple joints encompassing 34 clinical cases and in two amputated arms from November 1973 to August 1978. In 1984, Vaupel and Andrews described a case at the annual meeting of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine.2 A professional golfer presented with a 1-year history of chronic painful synovitis within the thumb MCP joint. Six months after arthroscopic synovectomy and débridement of a small chondral defect, the patient was able to return to his sport and was essentially pain free at a follow-up examination after almost 2-years.. These results were published in the American Journal of Sports Medicine, but hand surgeons were not affected by this novel technique.

In 1987, L.L. Wilkes, an orthopedic surgeon, presented the first series of rheumatoid pathology treated by arthroscopic means in the MCP joint.5 Arthroscopic rheumatoid synovectomy was performed on 13 joints in five patients with chronic rheumatoid arthritis. The patients lacked significant joint deformity, or even ulnar drift, but they did have significant synovitis within the recesses of the collateral ligament origins. Close clinical follow-up for 4 years demonstrated recurrence of pain and suggested that this technique altered progression of disease at the rheumatoid MCP joint only minimally. However, the transient pain relief and minimally invasive nature of the procedure led the investigator to conclude that it was a worthwhile procedure warranting further refinement. This innovative paper was published in the Journal of the Medical Association of Georgia but still did not influence the field of hand surgery.

This technique reached a broad audience of hand surgeons in 1994 through publication of a case report in the Journal of Hand Surgery (British edition).6 The patient was a young man who presented with swelling and recurrent locking of the MCP joints of the index and middle fingers bilaterally. This is a typical presentation for hemochromatosis, a rarely seen hematologic condition that is treated with phlebotomy and for which the joint manifestations are poorly understood. Until that time, the treatment of arthropathy was osteotomy, arthroplasty, and occasionally joint arthrodesis. Arthroscopy was an excellent alternative to open surgery, with better visualization of the joint, facilitating treatment of the synovitis, and more rapid recovery aided by its minimally invasive nature. The emphasis of the case report was on the condition itself, and no further recommendations were given beyond the suggestion that arthroscopic surgery was “of value.” Probably because the arthroscopic treatment was overshadowed by the unusual pathology being treated, the common clinical application of this technology was still not clear.

In 1995, Ryu and Fagan presented their series on treatment of the ulnar collateral ligament Stener lesion, which offered a common clinical application for this new technology.7 Their retrospective series study described arthroscopic reduction of Stener lesions in eight thumbs, with an average follow-up period of slightly more than 3 years. The technique involved reduction of the Stener lesion into the joint so that the avulsed ligament was juxtaposed to its insertion site on the base of the proximal phalanx. Previously, the ligament had been sitting outside the adductor aponeurosis and could not heal in appropriate position. After the reduction, the ligament ends were débrided and the joint pinned for stability. On removal of the cast, a brief course of therapy was introduced, and at follow-up no patient reported any pain or functional limitation. Range of motion was excellent, and strength parameters were equal to or greater than those of the thumb on the unaffected side. The only complication was a pin tract infection. These results indicated that an arthroscopic reduction of a Stener lesion could obviate the need for open repair with its inherent complications, such as prolonged recovery, stiffness, and dysesthetic scar. This series represented the first broad clinical indication for arthroscopic management of a small joint lesion. However, there was no mention of bony gamekeeper’s lesions and no comparative analysis with the open technique.

In April of 1999, Rozmaryn and Wei presented the first paper on the practical aspects of MCP arthroscopy, with amplification of the possible indications and advantages of this still new technique.8 This was not a clinical series discussing outcomes; rather they addressed the sentiment that the MCP joint is too small for arthroscopic procedures and provided a summary of the broad indications that could be treated with this procedure. They specifically mentioned joint synovectomies, débridement, and biopsies and supported the possibility of collateral ligament débridement and true ligament repair. They also reviewed removal of loose bodies, treatment of osteochondral lesions, management of periarticular lesions, and treatment of articular fractures. Although their article reviewed technical aspects and further delineated anatomic landmarks not discussed since Chen’s description 20 years earlier, it had little influence on field of hand surgery. They predicted, however, that the advantages of arthroscopic techniques and the indications would evolve over time.

Later in 1999, Slade and Gutow published a review paper, “Arthroscopy of the Metacarpophalangeal Joint,” in Hand Clinics.9 For the first time, a description of the technique was presented, including the surgical procedure, indications, and some typical cases. The investigators touched on complications and their management. They emphasized that small joint arthroscopy required small but resilient instrumentation and good knowledge of the anatomy of these joints. Their experience revealed broad indications for this methodology, although the treatment of degenerative joint disease was not discussed in any depth. Much more detailed surgical techniques were described, mainly regarding the management of intra-articular fractures, with supporting case studies. A challenging and innovative technique was described in which arthroscopy was combined with the application of small bone anchors for reattachment of injured collateral ligaments.

Slade and Gutlow9 pointed to the advantages of arthroscopy (e.g., rheumatoid synovectomy), as communicated by Patrick Ansah in Heidelberg. Ansah had begun comparing arthroscopic synovectomies and open procedures in joints of rheumatoid patients. In all of his cases, the surgeon and patient were impressed by the diminished postoperative swelling and improved rehabilitation with earlier return to activity provided by arthroscopic treatment. This unpublished series is an early illustration of the benefits of arthroscopic management of small joint degenerative disease. Coincidentally, a rheumatology paper published that same year discussed the use of mini-arthroscopy in MCP joints to stage the inflammatory arthropathy and to assist as a biopsy tool. This paper emphasized its clinical utility in the assessment of synovitis in rheumatoid patients but offered little discussion of the operative technique.10 The investigators commented that micro-arthroscopy provided the rheumatologist an objective technique for joint evaluation and visual guidance of synovial biopsy with increased accuracy and decreased risk of sampling errors. General anesthesia was not necessary, and the procedure could be done on an outpatient basis.

In 1999, Wei and associates presented a series of 21 arthroscopic synovectomies in patient with recalcitrant rheumatoid arthritis.11 Although this was predominantly an article describing the technique, the investigators reported that all patients had good short-term and commented that investigation of the utility of this procedure in other types of arthritis and other orthopedic conditions was warranted. They questioned the long-term effect of this procedure on joint preservation and the optimal timing for the operation in rheumatoid patients. We hope that increased use of MCP joint arthroscopy may answer these and many other questions.

Focusing on inflammatory small joint arthropathy, Sekiya and colleagues expanded on previous descriptions by evaluating 21 patients with rheumatoid arthritis in 27 PIP joints and 16 MCP joints.4 This was one of the earliest clinical descriptions of PIP joint arthroscopy, and it added further information about MCP joint arthroscopic surgery.4 The study authors found arthroscopic assessment of the articular surface and synovial membrane to be an excellent application of this tool and thought that more accurate biopsies could be taken. They speculated that arthroscopy for the small joints in the hands “will become a standard procedure in the near future.”4 Their study did not assess other types of arthritides.

In 2006, Badia reviewed basal joint and MCP arthroscopy, focusing on the development and indications for these still little-used techniques.12 Management of degenerative joint disease was discussed in a general fashion, with the conclusion that this is a useful indication, but long-term studies are necessary to determine its place in the hand surgeon’s armamentarium.

Treatment

Indications and Contraindications

Pathology of the MCP joint is relatively common. Although this discussion focuses on management of degenerative joint disease, acute trauma can involve any one of the MCP joints, with the thumb being the most commonly affected. Gamekeeper’s or skier’s thumb is a frequent injury seen in any hand surgeon’s practice. Ryu described arthroscopic management of the classic Stener lesion, and Badia presented a series of bony gamekeeper’s thumbs treated solely by arthroscopic means.13 Acute trauma can also involve the finger MCPs, with ligamentous and articular fractures occasionally seen.

The overuse syndromes may reflect a previously unrecognized acute injury that was not addressed or may be a more chronic type of synovitis of unknown origin. Arthroscopy of the MCP joints can assist in diagnosing the condition and can provide treatment. For example, vague but chronic pain of the index finger MCP joint is often seen in laborers. Initial treatment often consists of corticosteroid injection, but relief is frequently short lived, and pain recurs. Arthroscopic synovectomy and débridement offer a more definitive solution. In this scenario, the surgeon may see a frayed and scarred radial collateral ligament covered by dense synovitis, which often masks the underlying pathology. The surgeon must perform the synovectomy by mechanical means or radiofrequency ablation and must treat the underlying pathology to minimize the chance of recurrent synovitis and pain. This usually involves resection of the redundant capsular and ligamentous tissue, followed by radiofrequency shrinkage to restore some integrity and tautness to the capsuloligamentous complex. Avoidance of thermal injury is key, and the surgeon must be well versed in the use of small joint radiofrequency therapy.

Inflammatory arthritides, such as rheumatoid arthritis, usually are managed with the newer disease-modifying agents, oral steroids, and in the late stages, replacement arthroplasty if corticosteroid injections are not helpful or ulnar drift becomes pronounced. Occasionally, a mono-articular or pauci-articular form is encountered, and an arthroscopic biopsy may assist in making the diagnosis. Early involvement of these joints may warrant an arthroscopic synovectomy and capsular shrinkage, which may retard the process of joint destruction in response to cytokines. Research must be directed to assessing how arthroscopic synovial resection can alter this destructive inflammatory cascade. Currently, this procedure is best suited for retarding the destructive process in one to two of the most involved joints. Initial results are promising,4 but long-term results of this procedure have not been reported, and the basic science needs to be better understood.

Arthroscopic Technique

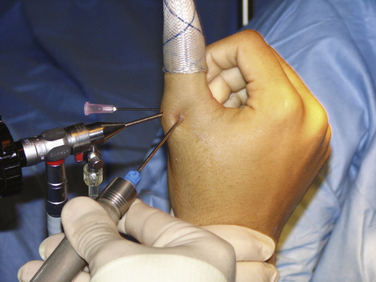

For small joint procedures, it is prudent to use local anesthesia and light sedation. Several milliliters of lidocaine are introduced into the joint after the hand is suspended using a single Chinese finger trap on the affected digit and 5 pounds of traction (Fig. 32-1). A small piece of gauze is usually tied around junction of the finger trap and skin to minimize chance of slippage. A shoulder holder may be used so that 360-degree access is available for fluoroscopy to guide pinning, but a standard wrist traction tower can be used. Adequate sedation is then achieved to allow elevation of the tourniquet for the necessary period.

The portals lie on either side of the often-palpable extensor tendon, and the surgeon can feel the indentation just underneath the proximal phalanx base. Occasionally, a third portal is used for outflow, and it is placed by palpating the capsule, identifying the interval as seen on the monitor, and then passing an 18-gauge needle (Fig. 32-2).

A synovectomy is initially performed to allow good joint visualization and identification of pathology. This is done with the 2.0-mm, full-radius shaver, revealing the capsule and ligamentous structures (Fig. 32-3). A radiofrequency ablator probe expedites this process but must be used sparingly, because the thin joint capsule and skin can suffer thermal injury.

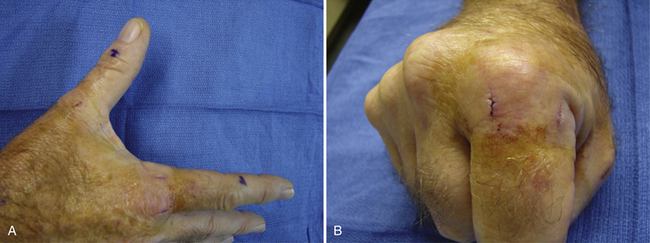

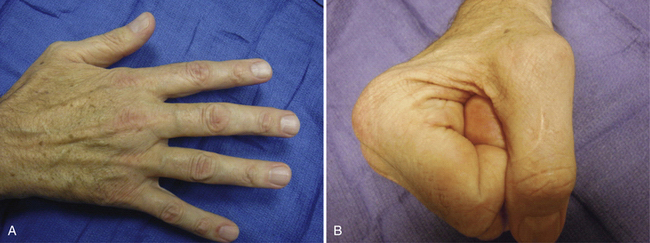

After the pathology is identified and appropriately addressed, the arthroscope is removed, and portals are closed with a skin adhesive such as Benzoin and Steri-Strips only. Suturing of portals will lead to scars that will be apparent on the dorsum of the hand or thumb. The thumb MCP is protected with a short arm thumb spica splint in extension, and the other digits usually require a dorsal MCP block splint in flexion. This arrangement allows the collateral ligaments to heal in their most taut, elongated position so that there is no resultant extension contracture. The period of immobilization is determined by the type and extent of pathology found during the arthroscopic procedure. Postoperative therapy is usually minimal and focuses on regaining range of motion and muscle strength (Figs. 4 to 6).

PROXIMAL INTERPHALANGEAL JOINT ARTHROSCOPY

Background

PIP joint arthroscopy is still considered an experimental procedure, and little has been written about it. However, Chen’s landmark paper described one clinical case and eight cadaveric studies using small joint arthroscopy of the PIP joint.1 The sole clinical case was use of the procedure in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis.

The only paper devoted solely to PIP joint arthroscopy was published by Thomsen and colleagues in a 2002 volume of the Journal of Hand Surgery.3 They described their findings, including suggested portal placement, in eight cadaveric PIP joints and in two clinical cases. They concluded that the technique was possible, although technically demanding, and that indications for the procedure needed to be defined. They suggested that synovectomy, infection, and loose body removal would likely constitute the main indications. One of the case studies involved a patient with rheumatoid arthritis, and the other was a patient who required removal of a loose body with a synovectomy.

Sekiya and coworkers analyzed the use of MCP and PIP arthroscopy in 21 patients with rheumatoid arthritis.4 Twenty-seven PIP joints and 16 MCP joints underwent rheumatoid synovectomy. The investigators concluded that it was a worthwhile procedure because biopsies could easily be performed and that synovectomies yielded clinical improvement. It was thought that small joint arthroscopy would become a standard procedure in the future, but the technique was limited by joint morphology and by the equipment available. The rigid nature and size of the arthroscope did not allow visualization of the palmar half of the middle phalanx base, and the condyles could be seen only by flexing the joint. Vertical traction was not used; instead, the finger was held horizontally while the arthroscope was introduced in the interval between central slip and lateral band. The study focused on rheumatoid disease, but the PIP joint is involved more often by osteoarthritis. A study assessing this more common pathology is needed.

Treatment

Arthroscopic Technique

Using a dorsal approach, the joint is insufflated with about 2 mL of lidocaine after adequate digital block anesthesia is achieved. The dorsal recesses are distended, allowing a 1.9- or 1.5-mm arthroscope to be inserted. The portals are on either side of the central slip, usually between that critical structure and the lateral bands. Sekiya and coworkers described a more lateral portal, passing through the transverse retinacular ligament and 1 to 2 mm dorsal to the midaxial line.4 Regardless, the palmar aspect of the joint is not visualized adequately, and flexible micro-arthroscopes may allow passing over the condyles to gain better visualization. This challenging approach necessitates smaller shavers to enter the confined space. The current 2.0-mm shavers provide limited tissue resection because of the small level of suction that can be generated. PIP joint arthroscopy is technically in its infancy.

1. Chen YC. Arthroscopy of the wrist and finger joints. Orthop Clin North Am. 1979;10:723-733.

2. Vaupel GL, Andrews JR. Diagnostic and operative arthroscopy of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint: a case report. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13:139-141.

3. Thomsen NO, Nielsen NS, Jørgensen U, Bojsen-Møller F. Arthroscopy of the proximal interphalangeal joints of the finger. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:253-255.

4. Sekiya I, Kobayashi M, Taneda Y, Matsui N. Arthroscopy of the proximal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints in rheumatoid hands. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:292-297.

5. Wilkes LL. Arthroscopic synovectomy in the rheumatoid metacarpophalangeal joint. J Med Assoc Ga. 1987;76:638-639.

6. Leclercq G, Schmitgen G, Verstreken J. Arthroscopic treatment of metacarpophalangeal arthropathy in haemochromatosis. J Hand Surg Br. 1994;19:212-214.

7. Ryu J, Fagan R. Arthroscopic treatment of acute complete thumb metacarpophalangeal ulnar collateral ligament tears. J Hand Surg Am. 1995;20:1037-1042.

8. Rozmaryn LM, Wei N. Metacarpophalangeal arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:333-337.

9. Slade JF3rd, Gutow AP. Arthroscopy of the metacarpophalangeal joint. Hand Clin. 1999;15:501-527.

10. Ostendorf B, Dann P, Wedekind F, et al. Miniarthroscopy of metacarpophalangeal joints in rheumatoid arthritis. Rating of diagnostic value in synovitis staging and efficiency of synovial biopsy. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1901-1908.

11. Wei N, Delauter SK, Erlichman MS, et al. Arthroscopic synovectomy of the metacarpophalangeal joint in refractory rheumatoid arthritis: a technique. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:265-268.

12. Badia A. Arthroscopy of the trapeziometacarpal and metacarpophalangeal joints. Chir Main. 2006;25(suppl 1):S259-S270.

13. Badia A. Arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation for bony gamekeeper’s thumb. Orthopedics. 2006;29:675-678.