Chapter 19 Decreasing the Risk of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Female Athletes

SCIENTIFIC RATIONALE AND SUPPORTING INVESTIGATIONS FOR SPORTSMETRICS NEUROMUSCULAR RETRAINING PROGRAM

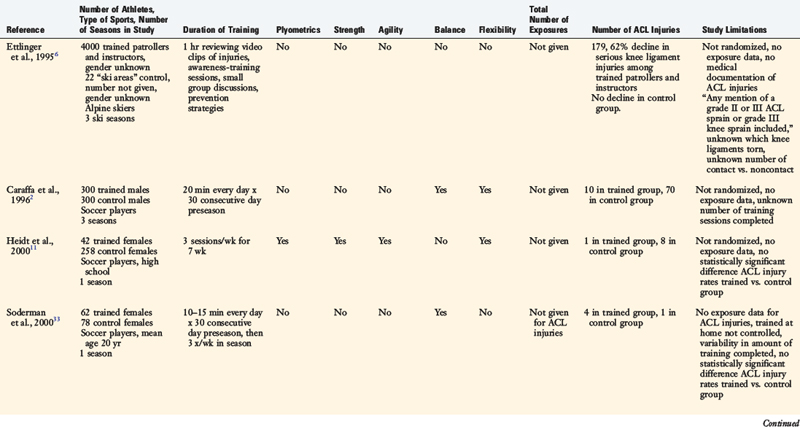

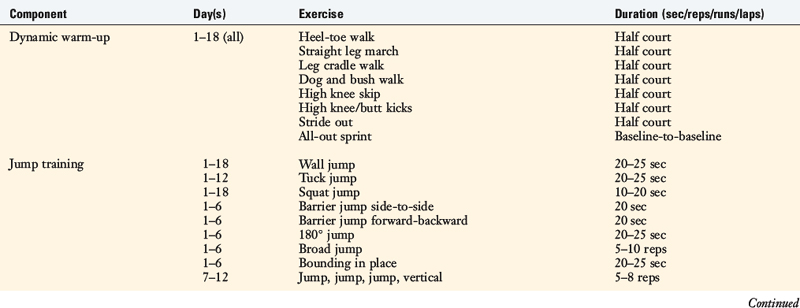

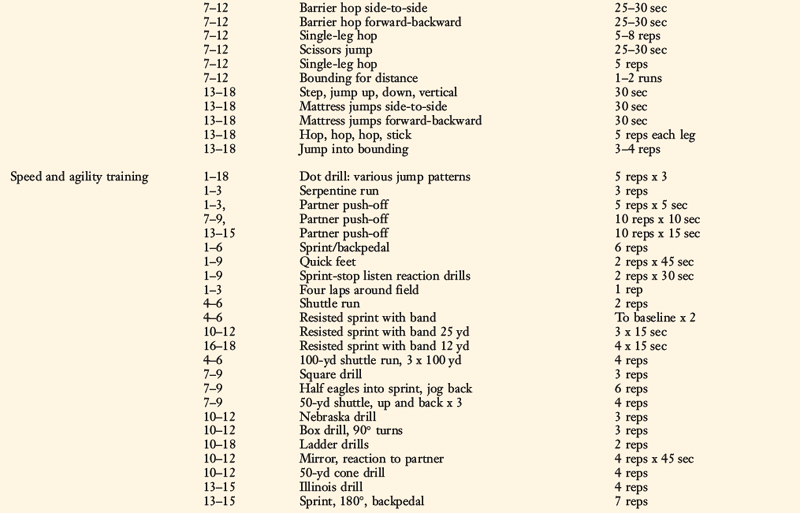

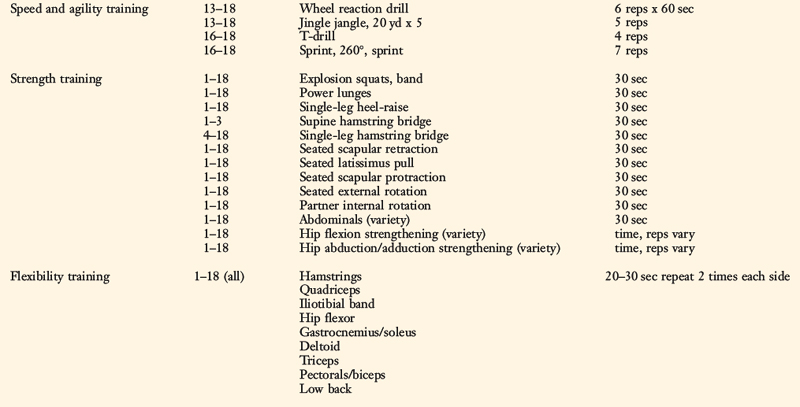

The purpose of this chapter is to present the scientific rationale, supporting data, and specific strategies for the implementation of a neuromuscular knee ligament injury prevention–training program, Sportsmetrics. Although many knee ligament injury prevention–training programs have been published,* few have presented scientific justification that the training effectively improved neuromuscular deficiencies and reduced the incidence of noncontact anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries in female athletes (Table 19-1). Some programs had small sample sizes and were thus underpowered to avoid the potential for a type II statistical error.7,11,28,29,33,35 Most studies were not randomized, and several did not contain a control group studied concurrently with a trained group. Although some investigations cited a reduction in noncontact ACL injury rates, others failed to find a statistically significant effect.11,28,29,33–35Some programs have been published even though the investigators did not follow athletes over a season or a period of time to determine whether a reduction in ACL injuries occurred as a result of preventive training. 14,16,21

The Sportsmetrics program is effective in inducing changes in neuromuscular indices in female athletes, because studies have shown improved overall lower limb alignment on a drop-jump test,24 increased hamstrings strength, 13,24,36 increased knee flexion angles on landing,13,31 and reduced deleterious abduction/adduction moments and ground reaction forces.13 Sportsmetrics also significantly reduces the risk of noncontact ACL injuries in female athletes participating in basketball, soccer, and volleyball.12

A pilot laboratory study was conducted at the authors’ institution using 11 high school female volleyball players to determine the effect of Sportsmetrics training on landing mechanics and lower extremity strength.13 The mean age of the female subjects was 15 ± 0.6 years, and they had participated in organized volleyball for an average of 2 ± 1 years before the study was initiated. A control group of 9 male subjects was selected and matched to the females according to height, weight, and age. The Sportsmetrics training program, described in detail later in this chapter, was performed 3 times a week (2-hr sessions) for 6 weeks. The athletes were taken through a series of tests before and after the training program. These tests included isokinetic muscle testing at 360°/sec and force analysis testing with a two-camera, video-based, optoelectronic digitizer for measuring motion and a multicomponent force plate for measuring ground reaction force. The subjects performed 10 jumps on the force plate that simulated volleyball jumping and landing maneuvers.

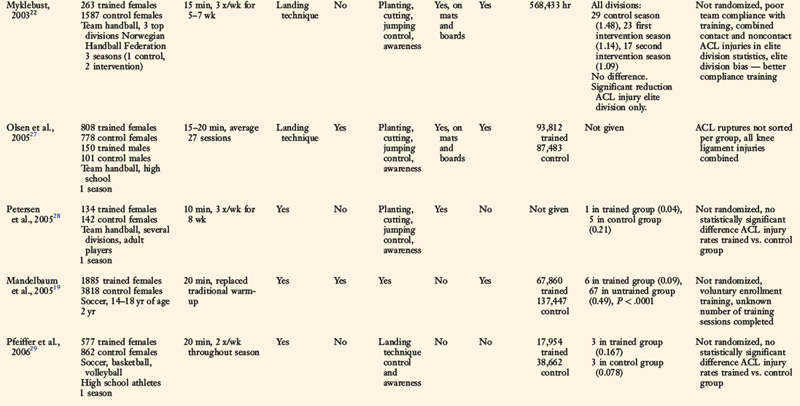

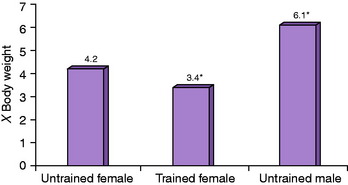

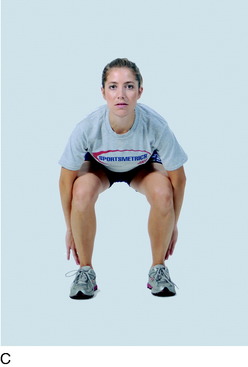

After 6 weeks of training, peak landing forces from a volleyball block jump decreased 22% (P = .006), or an average of 456N (103lb); all but 1 of the female subjects demonstrated a decrease in these forces (Fig. 19-1). Knee adduction and abduction moments, which induce a lateral or medial torque to the knee joint, decreased approximately 50% (Fig. 19-2). These moments were significant predictors of peak landing forces. The importance of this finding is that decreased abduction or abduction moments may lessen the risk of lift-off of the medial or lateral femoral condyle, improve tibiofemoral contact stabilizing forces,20 and reduce the risk of knee ligament injury.

A second study was conducted in a group of 62 high school female athletes to determine whether Sportsmetrics training altered lower limb alignment on a drop-jump task and isokinetic lower limb muscle strength.24 This investigation is described in detail in Chapter 16, Lower Limb Neuromuscular Control and Strength in Prepubescent and Adolescent Male and Female Athletes. Before training, 80% of the female athletes had a valgus overall lower limb alignment on landing from a drop-jump. After training, 34% of the females demonstrated this alignment (P < .0001). Significant increases were also noted after training in knee flexion peak torque in both the dominant and the nondominant limbs (P < .0001).

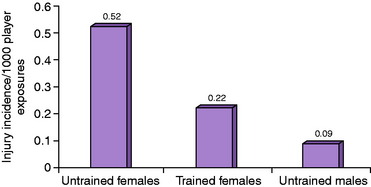

In order to determine whether Sportsmetrics training reduced the incidence of noncontact ACL injuries in female athletes, a controlled, prospective investigation was conducted in 1263 high school athletes.12 One group of 366 females underwent 6 weeks of Sportsmetrics training and a second group of 463 females was not trained. Included in the study was a group of 434 untrained male athletes. All athletes were followed throughout a single soccer, volleyball, or basketball season. Weekly reports submitted by athletic trainers included the number of practice and competition exposures and mechanism of injury. All ACL injuries were confirmed by arthroscopy, and medial collateral ligament (MCL) injuries were confirmed by manual valgus testing.

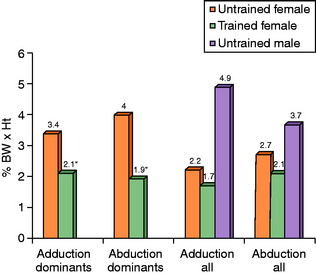

The total number of athlete-exposures were 23,138 for the untrained group, 17,222 for the trained group, and 21,390 for the male control group. There were 14 serious knee ligament injuries, which were sustained in 10 of 463 untrained female athletes (8 noncontact), 2 of 366 trained female athletes (0 noncontact), and 2 of 434 male athletes (1 noncontact). The knee injury incidence per 1000 athlete-exposures was 0.43 in untrained female athletes, 0.12 in trained female athletes, and 0.09 in male athletes (P = .02, chi-square analysis). Untrained female athletes had a 3.6 times higher incidence of knee injury than trained female athletes (P = .05) and 4.8 times higher than male athletes (P = .03). The incidence of knee injury in trained female athletes was not significantly different from that in untrained male athletes (Fig. 19-3; P = .86).

FIGURE 19-3 Serious knee injuries per 1000 player-exposures in soccer and basketball players.

(From Hewett, T. E.; Stroupe, A. L.; Nance, T. A.; Noyes, F. R.: Plyometric training in female athletes. Decreased impact forces and increased hamstring torques. Am J Sports Med 24:765–773, 1996.)

The risk factors that have been hypothesized to increase the potential for an ACL injury are discussed in Chapter 15, Risk Factors for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in the Female Athlete. The final position of the knee joint on landing, pivoting, and cutting is influenced by the center of gravity of the upper body and the trunk over the lower extremity. Equally important are trunk-hip adduction or abduction, foot-ankle pronation-supination, and foot separation distance. These effects add together to produce either a varus or a valgus moment about the knee joint that must be balanced by the lower limb musculature. If the athlete is off-balance, or contacts another player, a loss of trunk and lower limb control and position may occur and the knee joint may go into a hyperextended or valgus position. Although there are many potential mechanisms for ACL injury, it has been postulated that excessive valgus moments about the knee joint with subsequent high anterior tibial shear forces may be one of the most common to occur in females.8,15,18 Excessive valgus loading may result in decreased tibiofemoral contact, or condylar lift-off,20 and a reduction in the normal joint contact geometry that contributes to knee joint stability. This position, coupled with a highly activated quadriceps muscle that produces maximum anterior shear forces with the knee joint at low flexion angles (0°–30°),5,10,26 and a relatively inactive hamstrings musculature, could potentially lead to ACL rupture. The function of the hamstrings is dependent on the angle of knee flexion and degrees of external tibial rotation.25 The mechanical advantage of these muscles increases as the knee is flexed. At 0° of extension, the flexion force is only 49% of that generated at 90° of flexion. Withrow and coworkers37 measured the relative strain in the anteromedial region of the ACL in cadaver knees during a simulated jump landing maneuver. Increased hamstring muscle forces during the knee flexion phase significantly reduced the peak relative strain in the ACL by greater than 70% compared with the baseline condition (P = .005). The authors concluded that it may be possible to limit ACL strain by accentuating hip flexion during knee flexion phase of jump landings because this increases the tension in the active hamstring muscles.

The time in which an ACL rupture occurs was recently estimated to range from 17 to 50 msec after initial ground contact.17 It is evident that there is not enough time for an athlete, upon sensing a knee injury about to occur, to alter the body or lower extremity position to prevent the injury. In order to have a significant impact on reducing the incident rate of this injury, a training program must teach athletes to control the upper body, trunk, and lower body position; lower the center of gravity by increasing hip and knee flexion during activities; and develop muscular strength and techniques to land with decreased ground reaction forces. In addition, athletes should be taught to pre-position the body and lower extremity prior to initial ground contact in order to obtain the position of greatest knee joint stability and stiffness. The program should consist of a dynamic warm-up, plyometric jump training, strengthening exercises, aerobic conditioning, agility, and risk awareness training.9

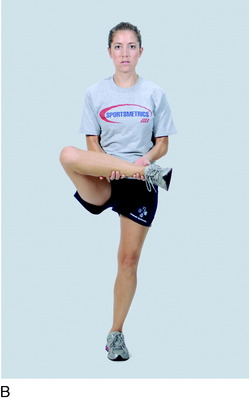

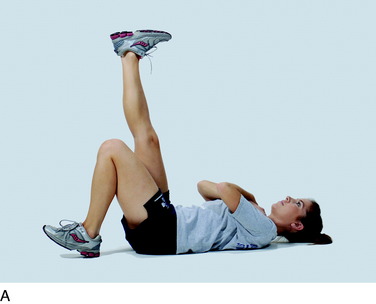

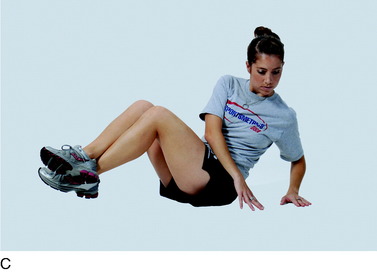

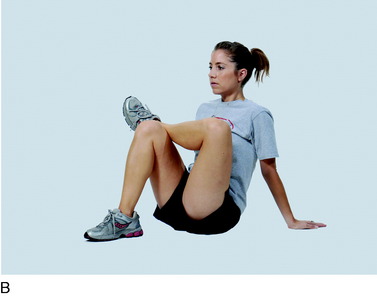

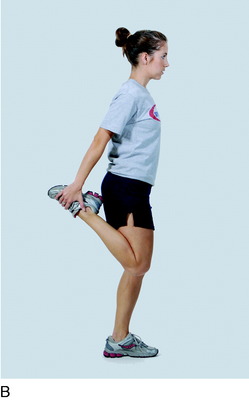

SPORTS INJURY TEST

The authors developed a sports injury test (SIT) in order to obtain a profile of each athlete before and after Sportsmetrics training. The SIT measures (1) knee and ankle position on landing and take-off from a drop-jump during a video test (described in detail in Chapter 16, Lower Limb Neuromuscular Control and Strength in Prepubescent and Adolescent Male and Female Athletes), (2) lower limb symmetry1,23 and a general assessment of lower limb control on single-leg hop tasks (Fig. 19-4), (3) isokinetic lower extremity muscle strength, (4) hamstring flexibility, and (5) vertical jump height. Athletes participating in sports-specific Sportsmetrics training programs, discussed later in this chapter, also undergo a 10-yard dash, a 20-yard dash, a T-drill run, and a 1-mile run. A history is collected for each athlete regarding prior injuries to the knees and ankles. The SIT is completed just prior to the initiation of training and within 1 week of completion of training.

SPORTSMETRICS NEUROMUSCULAR TRAINING PROGRAM COMPONENTS

Training may be accomplished either in classes led by an instructor who has completed certification training from the authors’ foundation or from an instructional step-by-step videotape series. Athletes who do not train with a certified instructor are encouraged to perform the training either in front of a mirror or with a partner so that mistakes in technique, form, and body alignment may be detected and corrected. A list of certified instructors and sites is available at http://www.sportsmetrics.net.

Dynamic Warm-up

Plyometrics/Jump Training

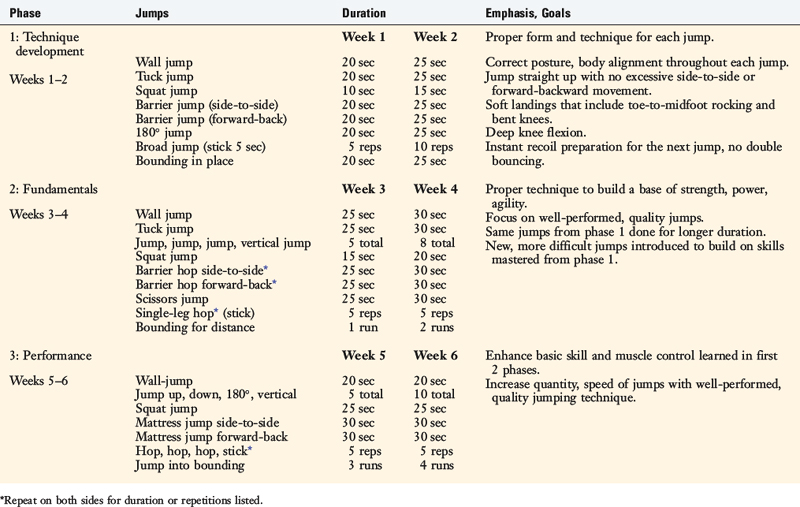

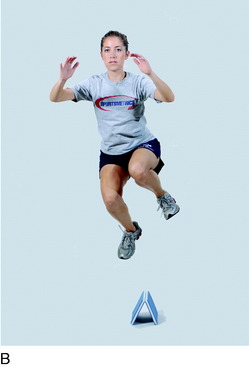

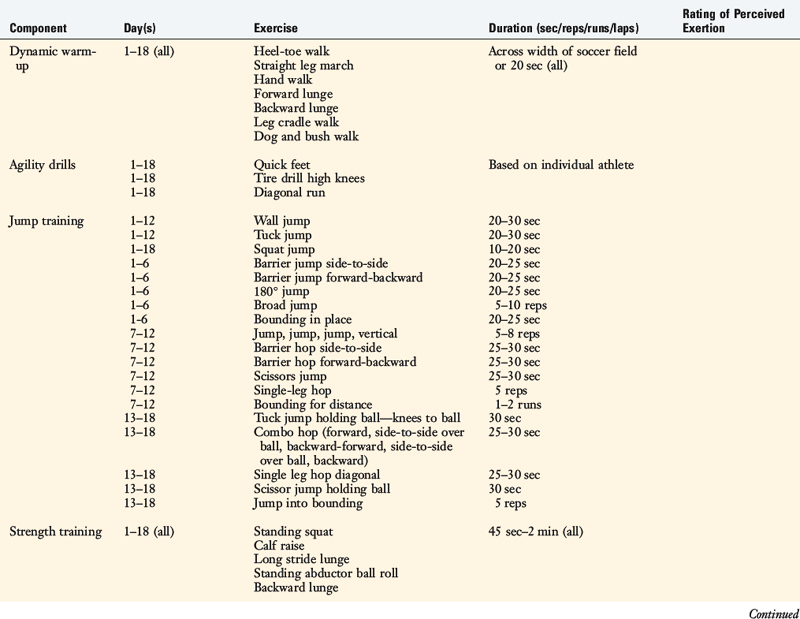

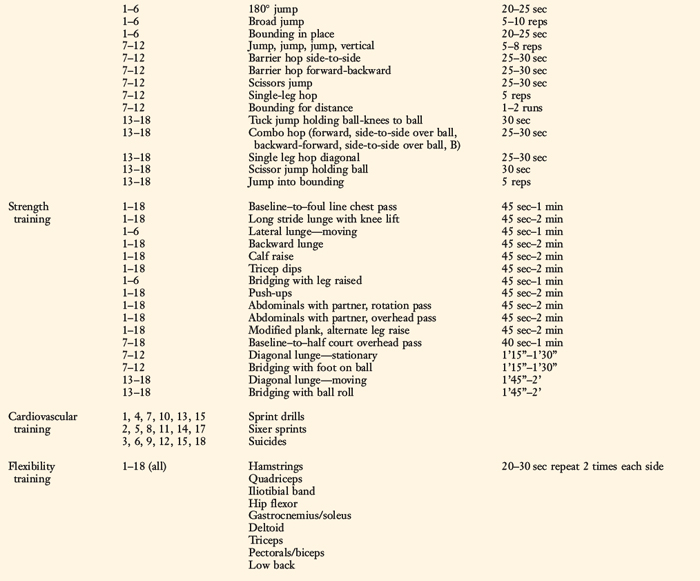

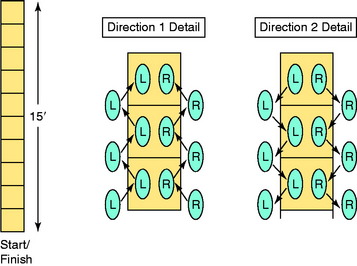

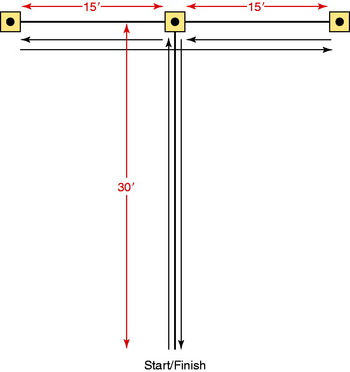

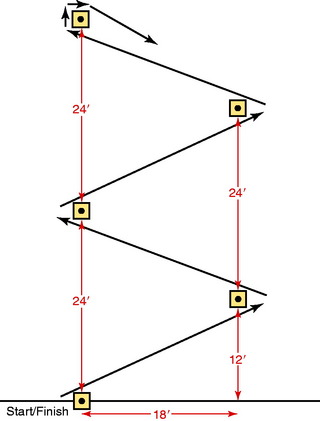

In reference to ACL injury prevention–training programs, Griffin and associates9 stated, “The rationale to include plyometric exercises is based on evidence that the stretch-shortening cycle activates neural, muscular, and elastic components and, therefore, should enhance joint stability (dynamic stiffening).” Plyometrics help develop muscle control and strength considered critical to reduce the risk of knee ligament injuries. These exercises are well known to increase muscular power, vertical jump height, acceleration speed, and running speed.3,4,32 However, if done improperly, these exercises would not be expected to have a beneficial effect in reducing the risk of a noncontact ACL injury. Therefore, the philosophy of the plyometric and jump-training component in the Sportsmetrics program is to place a major emphasis on correct jumping and techniques throughout the 6 weeks of training. Specific drills and instruction are used to teach the athlete to pre-position the entire body safely when accelerating or decelerating on landing. The selection and progression of the exercises entail neuromuscular retraining and proceed from simple jumping drills (to instill correct form) to multidirectional, single-foot hops and plyometrics with an emphasis on quick turnover (to add movements that mimic sports-specific motions). The jump training is divided into three 2-week phases. Each 2-week phase has a different training focus and the exercises change correspondingly (Table 19-2).

Strength Training

Flexibility

SPORTSMETRICS TRAINING PROGRAM OPTIONS

Sportsmetrics Warm-up for Injury Prevention and Performance

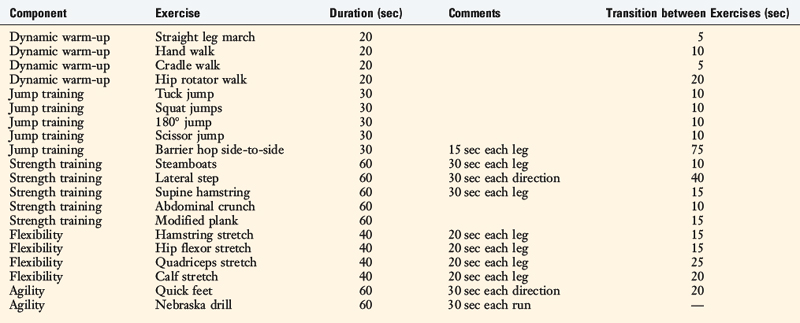

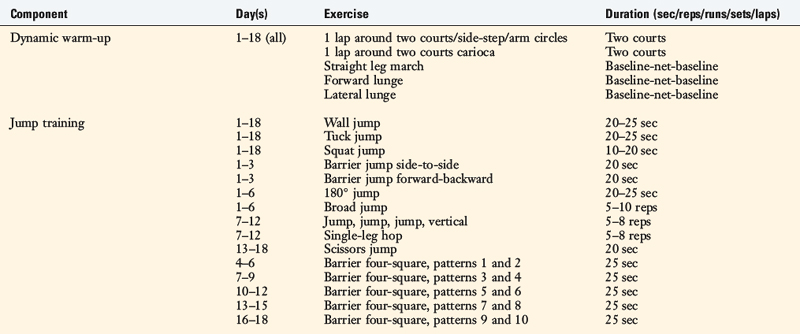

Designed as a maintenance program, WIPP is recommended upon completion of the 6 weeks of formal Sportsmetrics training to continue to instill the skills and techniques learned during Sportsmetrics for the athlete’s entire sports season. WIPP training is conducted in place of the normal warm-up before a practice or a game and lasts approximately 20 minutes. The program integrates select elements from the four basic components of Sportsmetrics and focuses on the essential training concepts of control of the upper body, trunk, and lower body position on landing, increased hip and knee flexion angles on landing, and techniques to land softly to decrease ground reaction forces (Table 19-3).

Sports-Specific Training

Sportsmetrics Soccer and Basketball

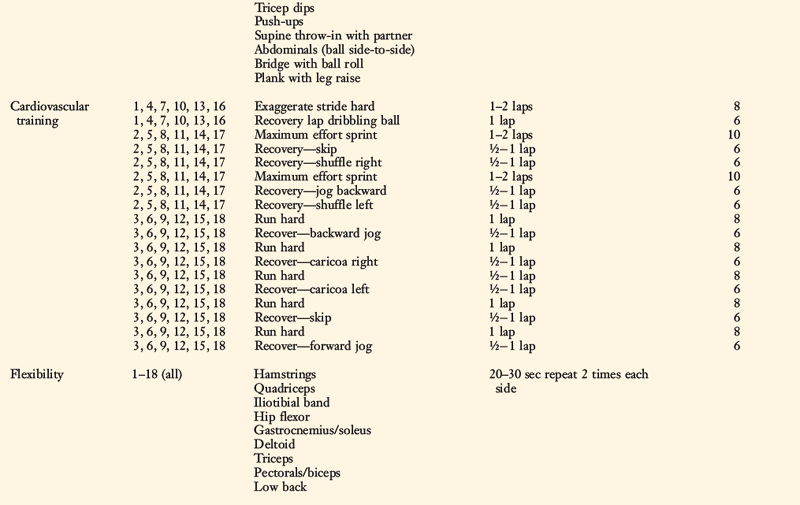

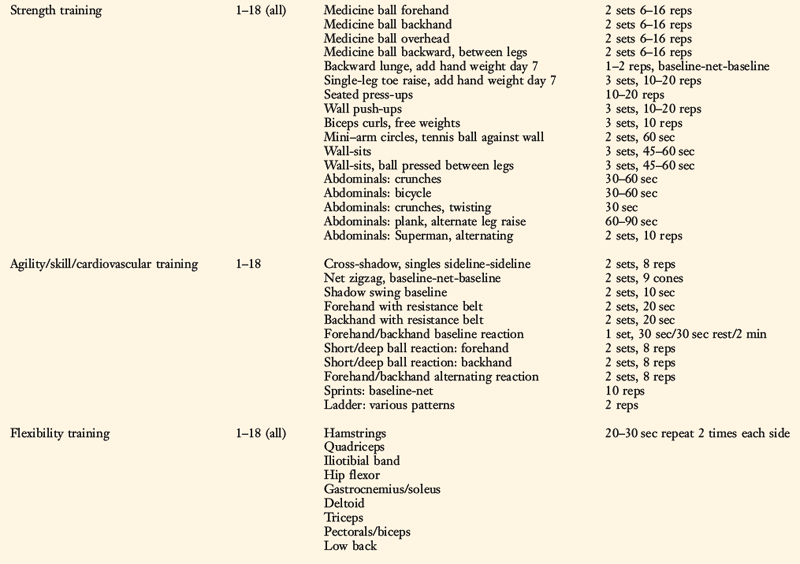

Sportsmetrics Soccer includes the components of Sportsmetrics in addition to agility drills and three different cardiovascular workouts that are both aerobic and anaerobic (Table 19-4). Each cardiovascular workout has a slightly different combination of short bursts of hard running and longer-distance/lower-intensity movements. The intensity of each running maneuver is monitored using a Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale from 1 to 10, with a rating of 1 indicating the lightest intensity and a rating of 10 designating an all-out maximum effort.

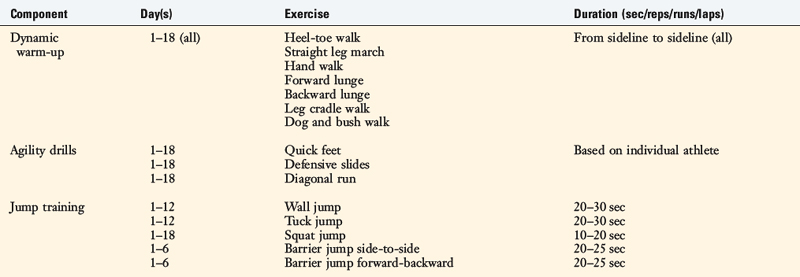

Sportsmetrics Basketball was designed to address fundamental strength, coordination, agility, and aerobic fitness (Table 19-5). The dynamic warm-up, jump/plyometric drills, and stretches are essentially the same as the original Sportsmetrics program with the addition of a basketball whenever possible to enhance balance, postural/body control, and trunk strength. The strength exercises are functional body weight exercises emphasizing total body conditioning. Agility drills and cardiovascular workouts, based upon basketball movement patterns and drills, round out the training.

Sportsmetrics Tennis

Although not considered a high-risk sport for noncontact ACL injuries, tennis carries the risk of other lower extremity injuries and overuse syndromes. A recent review of the literature regarding tennis injuries found that the lower extremity was the most common area injured.30 The concepts developed in traditional Sportsmetrics of decreased landing forces, increased knee and hip flexion angles during activity, improvement in balance and posture, and increased strength and agility may be effective in reducing the risk of other lower extremity injuries during tennis. Emphasis is placed on the athlete performing every exercise or drill with proper technique, body alignment, and form. The program incorporates strength training, cardiovascular conditioning, and skill/agility drills that match the demands of the sport (Table 19-6). Performed three times a week for 6 weeks, the training may be conducted during season or off-season. All training is performed on the court, and the authors recommend the use of clay courts if possible.

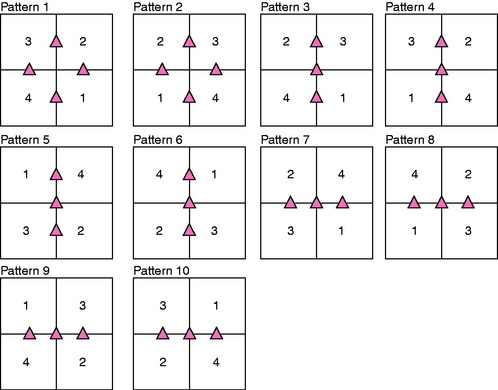

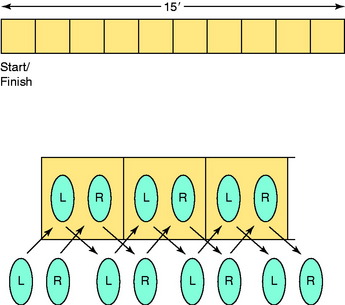

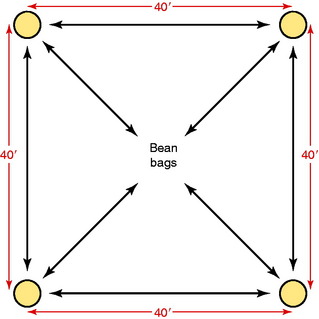

In addition to the jumps from the traditional Sportsmetrics program, the athletes perform level surface box (four-square) hops over barriers in a variety of patterns of increasing difficulty each week (Fig. 19-39). The patterns involve right-left, forward-backward, and diagonal directions to simulate the constant change of direction required during competitive tennis. While maintaining proper body position and knee flexion angles, the athletes are encouraged to perform as many hops as possible in 20 to 25 seconds.

Sportsmetrics Speed and Conditioning Program

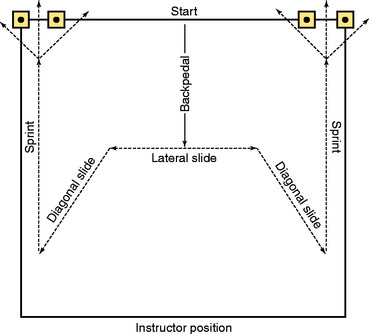

The Sportsmetrics Speed and Conditioning Program incorporates complex conditioning in addition to the other components of Sportsmetrics. The conditioning program encompasses a series of vigorous speed and agility drills comprising quick feet, sharp cuts, straight sprints, backward running, and unpredicted agility patterns (Table 19-7). With each drill, athletes concentrate on correct running form, body posture, and proper technique associated with cutting, pivoting, and decelerating. The entire program may be performed on a court or field with minimal equipment. It should be conducted in the athlete’s off or preparatory season, 3 days a week for 6 weeks. A few examples of the speed and agility training drills are listed later. The four-square hops shown in Figure 19-39 are included in the training (termed dot drill). This program is under prospective investigation to determine its effectiveness on both improving performance and reducing the rate of ACL noncontact injuries.

STRATEGIES FOR IMPLEMENTATION OF NEUROMUSCULAR TRAINING

Educate Health Care Professionals to Conduct Formal Neuromuscular Training

In order to implement Sportsmetrics on a national basis, a formal course was devised to educate and certify health care professionals and coaches who wished to conduct training in their communities. The 13-hour formal course teaches (1) the theories of why female athletes have an increased incidence of serious knee ligament injuries compared with males, (2) the scientific basis of Sportsmetrics, (3) the necessity for neuromuscular training versus plyometric performance-enhancement training, (4) the verbal cues and methods required to teach the program to produce a change in landing mechanics and body positioning, (5) the differences between Sportsmetrics and other neuromuscular-training programs, (6) marketing strategies and ways to implement training in the community, (7) the necessity to conduct sports injury testing (see Chapter 16, Lower Limb Neuromuscular Control and Strength in Prepubescent and Adolescent Male and Female Athletes) and produce research data, and (8) for those involved in rehabilitation clinics, the implementation of Sportsmetrics as a component of rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction.

Participants are given a detailed demonstration of every jump and spend a few hours practicing the jumps themselves and conducting mock instructions for the teaching staff. Each participant is taken through the sports injury test and given step-by-step instruction on the video drop-jump test (see Chapter 16, Lower Limb Neuromuscular Control and Strength in Prepubescent and Adolescent Male and Female Athletes). A formal written examination is conducted to ascertain that the participant has adequate knowledge of knee anatomy and strength training and plyometric concepts. A practical examination is done in which the participant trains a local athlete to demonstrate to our staff that he or she understands the correct verbal cues and training methodology to produce the desired result of proper body positioning and landing mechanics.

1 Barber S.D., Noyes F.R., Mangine R.E., et al. Quantitative assessment of functional limitations in normal and anterior cruciate ligament–deficient knees. Clin Orthop. 1990;255:204-214.

2 Caraffa A., Cerulli G., Projetti M., et al. Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer. A prospective controlled study of proprioceptive training. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1996;4:19-21.

3 Chu D.A. Explosive power. In: Foran B., editor. High-Performance Sports Conditioning. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2001:83-98.

4 Delecluse C., Van Coppenolle H., Willems E., et al. Influence of high-resistance and high-velocity training on sprint performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:1203-1209.

5 DeMorat G., Weinhold P., Blackburn T., et al. Aggressive quadriceps loading can induce noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:477-483.

6 Ettlinger C.F., Johnson R.J., Shealy J.E. A method to help reduce the risk of serious knee sprains incurred in alpine skiing. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:531-537.

7 Greenfield M.L., Kuhn J.E., Wojtys E.M. A statistics primer. Power analysis and sample size determination. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:138-140.

8 Griffin L.Y., et al. Noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: risk factors and prevention strategies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:141-150.

9 Griffin L.Y., et al. Understanding and preventing noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: a review of the Hunt Valley II meeting, January 2005. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1512-1532.

10 Grood E.S., Suntay W.J., Noyes F.R., Butler D.L. Biomechanics of the knee-extension exercise. Effect of cutting the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:725-734.

11 Heidt R.S.Jr., Sweeterman L.M., Carlonas R.L., et al. Avoidance of soccer injuries with preseason conditioning. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:659-662.

12 Hewett T.E., Lindenfeld T.N., Riccobene J.V., Noyes F.R. The effect of neuromuscular training on the incidence of knee injury in female athletes. A prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:699-706.

13 Hewett T.E., Stroupe A.L., Nance T.A., Noyes F.R. Plyometric training in female athletes. Decreased impact forces and increased hamstring torques. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:765-773.

14 Holm I., Fosdahl M.A., Friis A., et al. Effect of neuromuscular training on proprioception, balance, muscle strength, and lower limb function in female team handball players. Clin J Sport Med. 2004;14:88-94.

15 Hutchinson M.R., Ireland M.L. Knee injuries in female athletes. Sports Med. 1995;19:288-302.

16 Irmischer B.S., Harris C., Pfeiffer R.P., et al. Effects of a knee ligament injury prevention exercise program on impact forces in women. J Strength Cond Res. 2004;18:703-707.

17 Krosshaug T., Nakamae A., Boden B.P., et al. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury in basketball: video analysis of 39 cases. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:359-367.

18 Malinzak R.A., Colby S.M., Kirkendall D.T., et al. A comparison of knee joint motion patterns between men and women in selected athletic tasks. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2001;16:438-445.

19 Mandelbaum B.R., Silvers H.J., Watanabe D.S., et al. Effectiveness of a neuromuscular and proprioceptive training program in preventing anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1003-1010.

20 Markolf K.L., Burchfield D.M., Shapiro M.M., et al. Combined knee loading states that generate high anterior cruciate ligament forces. J Orthop Res. 1995;13:930-935.

21 Myer G.D., Ford K.R., McLean S.G., Hewett T.E. The effects of plyometric versus dynamic stabilization and balance training on lower extremity biomechanics. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:445-455.

22 Myklebust G., Engebretsen L., Braekken I.H., et al. Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female team handball players: a prospective intervention study over three seasons. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13:71-78.

23 Noyes F.R., Barber S.D., Mangine R.E. Abnormal lower limb symmetry determined by function hop tests after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:513-518.

24 Noyes F.R., Barber-Westin S.D., Fleckenstein C., et al. The drop-jump screening test: difference in lower limb control by gender and effect of neuromuscular training in female athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:197-207.

25 Noyes F.R., Sonstegard D.A. Biomechanical function of the pes anserinus at the knee and the effect of its transplantation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:1225-1241.

26 O’Connor J.J. Can muscle co-contraction protect knee ligaments after injury or repair? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:41-48.

27 Olsen O.E., Myklebust G., Engebretsen L., et al. Exercises to prevent lower limb injuries in youth sports: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;330(7489):449.

28 Petersen W., et al. A controlled prospective case control study of a prevention training program in female team handball players: the German experience. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2005;125:614-621.

29 Pfeiffer R.P., Shea K.G., Roberts D., et al. Lack of effect of a knee ligament injury prevention program on the incidence of noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1769-1774.

30 Pluim B.M., Staal J.B., Windler G.E., Jayanthi N. Tennis injuries: occurrence, aetiology, and prevention. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:415-423.

31 Prapavessis H., McNair P.J. Effects of instruction in jumping technique and experience jumping on ground reaction forces. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29:352-356.

32 Rimmer E., Sleivert G. Effects of a plyometric intervention program on sprint performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2000;14:295-301.

33 Soderman K., Werner S., Pietila T., et al. Balance board training: prevention of traumatic injuries of the lower extremities in female soccer players? A prospective randomized intervention study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:356-363.

34 Wedderkopp N., Kaltoft M., Holm R., Froberg K. Comparison of two intervention programmes in young female players in European handball—with and without ankle disc. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2003;13:371-375.

35 Wedderkopp N., Kaltoft M., Lundgaard B., et al. Prevention of injuries in young female players in European team handball. A prospective intervention study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1999;9:41-47.

36 Wilkerson G.B., Colston M.A., Short N.I., et al. Neuromuscular changes in female collegiate athletes resulting from a plyometric jump-training program. J Athl Train. 2004;39:17-23.

37 Withrow T.J., Huston L.J., Wojtys E.M., Ashton-Miller J.A. Effect of varying hamstring tension on anterior cruciate ligament strain during in vitro impulsive knee flexion and compression loading. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:815-823.