1 |

The Practice of Medicine |

THE PHYSICIAN IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

No greater opportunity, responsibility, or obligation can fall to the lot of a human being than to become a physician. In the care of the suffering, [the physician] needs technical skill, scientific knowledge, and human understanding…. Tact, sympathy, and understanding are expected of the physician, for the patient is no mere collection of symptoms, signs, disordered functions, damaged organs, and disturbed emotions. [The patient] is human, fearful, and hopeful, seeking relief, help, and reassurance.

—Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 1950

The practice of medicine has changed in significant ways since the first edition of this book appeared more than 60 years ago. The advent of molecular genetics, molecular and systems biology, and molecular pathophysiology; sophisticated new imaging techniques; and advances in bioinformatics and information technology have contributed to an explosion of scientific information that has fundamentally changed the way physicians define, diagnose, treat, and attempt to prevent disease. This growth of scientific knowledge is ongoing and accelerating.

The widespread use of electronic medical records and the Internet have altered the way doctors practice medicine and access and exchange information (Fig. 1-1). As today’s physicians strive to integrate copious amounts of scientific knowledge into everyday practice, it is critically important that they remember two things: first, that the ultimate goal of medicine is to prevent disease and treat patients; and second, that despite more than 60 years of scientific advances since the first edition of this text, cultivation of the intimate relationship between physician and patient still lies at the heart of successful patient care.

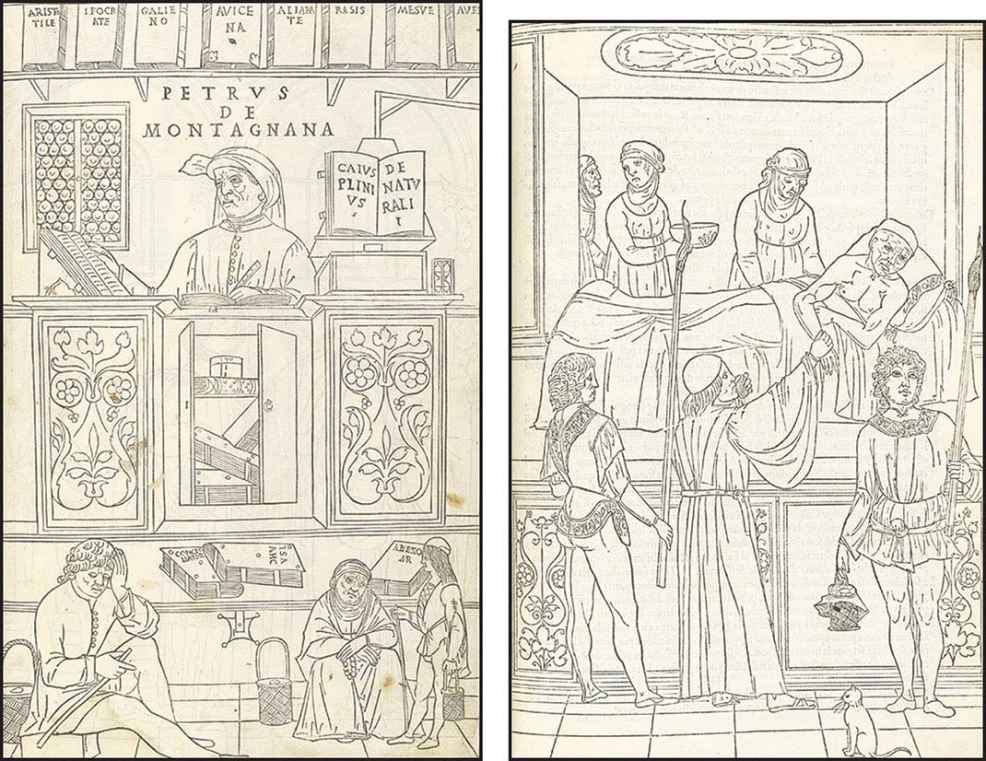

FIGURE 1-1 Woodcuts from Johannes de Ketham’s Fasciculus Medicinae, the first illustrated medical text ever printed, show methods of information access and exchange in medical practice during the early Renaissance. Initially published in 1491 for use by medical students and practitioners, Fasciculus Medicinae appeared in six editions over the next 25 years. Left: Petrus de Montagnana, a well-known physician and teacher at the University of Padua and author of an anthology of instructive case studies, consults medical texts dating from antiquity up to the early Renaissance. Right: A patient with plague is attended by a physician and his attendants. (Courtesy, U.S. National Library of Medicine.)

THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MEDICINE

Deductive reasoning and applied technology form the foundation for the solution to many clinical problems. Spectacular advances in biochemistry, cell biology, and genomics, coupled with newly developed imaging techniques, allow access to the innermost parts of the cell and provide a window into the most remote recesses of the body. Revelations about the nature of genes and single cells have opened a portal for formulating a new molecular basis for the physiology of systems. Increasingly, physicians are learning how subtle changes in many different genes can affect the function of cells and organisms. Researchers are deciphering the complex mechanisms by which genes are regulated. Clinicians have developed a new appreciation of the role of stem cells in normal tissue function; in the development of cancer, degenerative diseases, and other disorders; and in the treatment of certain diseases. Entirely new areas of research, including studies of the human microbiome, have become important in understanding both health and disease. The knowledge gleaned from the science of medicine continues to enhance physicians’ understanding of complex disease processes and provide new approaches to treatment and prevention. Yet skill in the most sophisticated applications of laboratory technology and in the use of the latest therapeutic modality alone does not make a good physician.

When a patient poses challenging clinical problems, an effective physician must be able to identify the crucial elements in a complex history and physical examination; order the appropriate laboratory, imaging, and diagnostic tests; and extract the key results from densely populated computer screens to determine whether to treat or to “watch.” As the number of tests increases, so does the likelihood that some incidental finding, completely unrelated to the clinical problem at hand, will be uncovered. Deciding whether a clinical clue is worth pursuing or should be dismissed as a “red herring” and weighing whether a proposed test, preventive measure, or treatment entails a greater risk than the disease itself are essential judgments that a skilled clinician must make many times each day. This combination of medical knowledge, intuition, experience, and judgment defines the art of medicine, which is as necessary to the practice of medicine as is a sound scientific base.

CLINICAL SKILLS

History-Taking The written history of an illness should include all the facts of medical significance in the life of the patient. Recent events should be given the most attention. Patients should, at some early point, have the opportunity to tell their own story of the illness without frequent interruption and, when appropriate, should receive expressions of interest, encouragement, and empathy from the physician. Any event related by a patient, however trivial or seemingly irrelevant, may provide the key to solving the medical problem. In general, only patients who feel comfortable with the physician will offer complete information; thus putting the patient at ease to the greatest extent possible contributes substantially to obtaining an adequate history.

An informative history is more than an orderly listing of symptoms. By listening to patients and noting the way in which they describe their symptoms, physicians can gain valuable insight. Inflections of voice, facial expression, gestures, and attitude (i.e., “body language”) may offer important clues to patients’ perception of their symptoms. Because patients vary in their medical sophistication and ability to recall facts, the reported medical history should be corroborated whenever possible. The social history also can provide important insights into the types of diseases that should be considered. The family history not only identifies rare Mendelian disorders within a family but often reveals risk factors for common disorders, such as coronary heart disease, hypertension, and asthma. A thorough family history may require input from multiple relatives to ensure completeness and accuracy; once recorded, it can be updated readily. The process of history-taking provides an opportunity to observe the patient’s behavior and to watch for features to be pursued more thoroughly during the physical examination.

The very act of eliciting the history provides the physician with an opportunity to establish or enhance the unique bond that forms the basis for the ideal patient-physician relationship. This process helps the physician develop an appreciation of the patient’s view of the illness, the patient’s expectations of the physician and the health care system, and the financial and social implications of the illness for the patient. Although current health care settings may impose time constraints on patient visits, it is important not to rush the history-taking. A hurried approach may lead patients to believe that what they are relating is not of importance to the physician, and thus they may withhold relevant information. The confidentiality of the patient-physician relationship cannot be overemphasized.

Physical Examination The purpose of the physical examination is to identify physical signs of disease. The significance of these objective indications of disease is enhanced when they confirm a functional or structural change already suggested by the patient’s history. At times, however, physical signs may be the only evidence of disease.

The physical examination should be methodical and thorough, with consideration given to the patient’s comfort and modesty. Although attention is often directed by the history to the diseased organ or part of the body, the examination of a new patient must extend from head to toe in an objective search for abnormalities. Unless the physical examination is systematic and is performed consistently from patient to patient, important segments may be omitted inadvertently. The results of the examination, like the details of the history, should be recorded at the time they are elicited—not hours later, when they are subject to the distortions of memory. Skill in physical diagnosis is acquired with experience, but it is not merely technique that determines success in eliciting signs of disease. The detection of a few scattered petechiae, a faint diastolic murmur, or a small mass in the abdomen is not a question of keener eyes and ears or more sensitive fingers but of a mind alert to those findings. Because physical findings can change with time, the physical examination should be repeated as frequently as the clinical situation warrants.

Given the many highly sensitive diagnostic tests now available (particularly imaging techniques), it may be tempting to place less emphasis on the physical examination. Indeed, many patients are seen by consultants after a series of diagnostic tests have been performed and the results are known. This fact should not deter the physician from performing a thorough physical examination since important clinical findings may have escaped detection by the barrage of prior diagnostic tests. The act of examining (touching) the patient also offers an opportunity for communication and may have reassuring effects that foster the patient-physician relationship.

Diagnostic Studies Physicians rely increasingly on a wide array of laboratory tests to solve clinical problems. However, accumulated laboratory data do not relieve the physician from the responsibility of carefully observing, examining, and studying the patient. It is also essential to appreciate the limitations of diagnostic tests. By virtue of their impersonal quality, complexity, and apparent precision, they often gain an aura of certainty regardless of the fallibility of the tests themselves, the instruments used in the tests, and the individuals performing or interpreting the tests. Physicians must weigh the expense involved in laboratory procedures against the value of the information these procedures are likely to provide.

Single laboratory tests are rarely ordered. Instead, physicians generally request “batteries” of multiple tests, which often prove useful. For example, abnormalities of hepatic function may provide the clue to nonspecific symptoms such as generalized weakness and increased fatigability, suggesting a diagnosis of chronic liver disease. Sometimes a single abnormality, such as an elevated serum calcium level, points to a particular disease, such as hyperparathyroidism or an underlying malignancy.

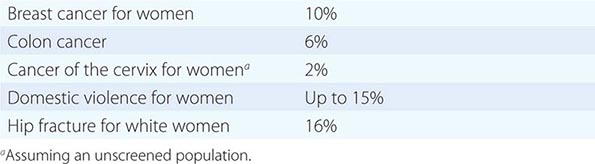

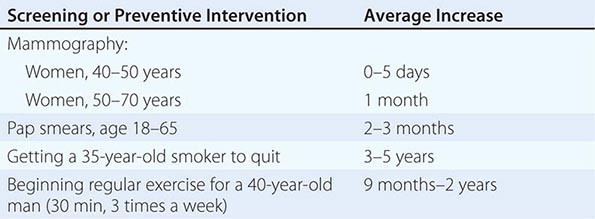

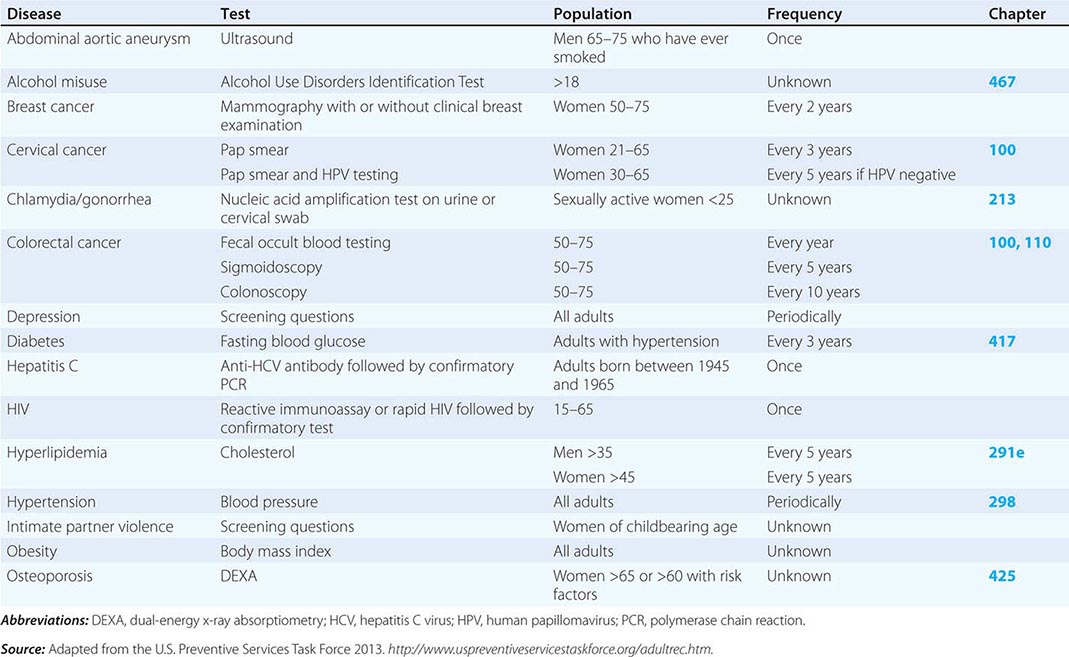

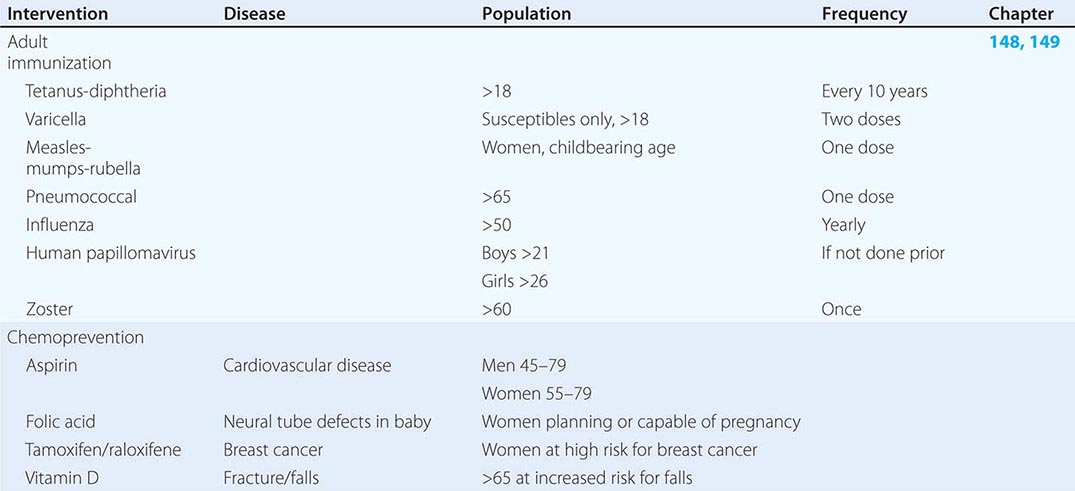

The thoughtful use of screening tests (e.g., measurement of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol) may be of great value. A group of laboratory values can conveniently be obtained with a single specimen at relatively low cost. Screening tests are most informative when they are directed toward common diseases or disorders and when their results indicate whether other useful—but often costly—tests or interventions are needed. On the one hand, biochemical measurements, together with simple laboratory determinations such as blood count, urinalysis, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, often provide a major clue to the presence of a pathologic process. On the other hand, the physician must learn to evaluate occasional screening-test abnormalities that do not necessarily connote significant disease. An in-depth workup after the report of an isolated laboratory abnormality in a person who is otherwise well is almost invariably wasteful and unproductive. Because so many tests are performed routinely for screening purposes, it is not unusual for one or two values to be slightly abnormal. Nevertheless, even if there is no reason to suspect an underlying illness, tests yielding abnormal results ordinarily are repeated to rule out laboratory error. If an abnormality is confirmed, it is important to consider its potential significance in the context of the patient’s condition and other test results.

The development of technically improved imaging studies with greater sensitivity and specificity proceeds apace. These tests provide remarkably detailed anatomic information that can be a pivotal factor in medical decision-making. Ultrasonography, a variety of isotopic scans, CT, MRI, and positron emission tomography have supplanted older, more invasive approaches and opened new diagnostic vistas. In light of their capabilities and the rapidity with which they can lead to a diagnosis, it is tempting to order a battery of imaging studies. All physicians have had experiences in which imaging studies revealed findings that led to an unexpected diagnosis. Nonetheless, patients must endure each of these tests, and the added cost of unnecessary testing is substantial. Furthermore, investigation of an unexpected abnormal finding may be associated with risk and/or expense and may lead to the diagnosis of an irrelevant or incidental problem. A skilled physician must learn to use these powerful diagnostic tools judiciously, always considering whether the results will alter management and benefit the patient.

PRINCIPLES OF PATIENT CARE

Evidence-Based Medicine Evidence-based medicine refers to the making of clinical decisions that are formally supported by data, preferably data derived from prospectively designed, randomized, controlled clinical trials. This approach is in sharp contrast to anecdotal experience, which is often biased. Unless they are attuned to the importance of using larger, more objective studies for making decisions, even the most experienced physicians can be influenced to an undue extent by recent encounters with selected patients. Evidence-based medicine has become an increasingly important part of routine medical practice and has led to the publication of many practice guidelines.

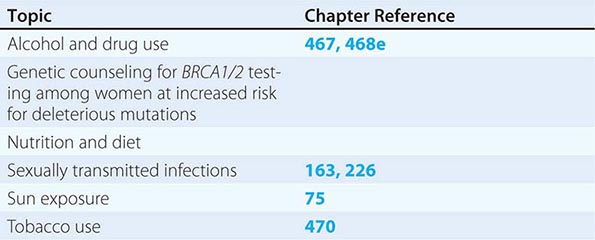

Practice Guidelines Many professional organizations and government agencies have developed formal clinical-practice guidelines to aid physicians and other caregivers in making diagnostic and therapeutic decisions that are evidence-based, cost-effective, and most appropriate to a particular patient and clinical situation. As the evidence base of medicine increases, guidelines can provide a useful framework for managing patients with particular diagnoses or symptoms. Clinical guidelines can protect patients—particularly those with inadequate health care benefits—from receiving substandard care. These guidelines also can protect conscientious caregivers from inappropriate charges of malpractice and society from the excessive costs associated with the overuse of medical resources. There are, however, caveats associated with clinical-practice guidelines since they tend to oversimplify the complexities of medicine. Furthermore, groups with different perspectives may develop divergent recommendations regarding issues as basic as the need for screening of women in their forties by mammography or of men over age 50 by serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) assay. Finally, guidelines, as the term implies, do not—and cannot be expected to—account for the uniqueness of each individual and his or her illness. The physician’s challenge is to integrate into clinical practice the useful recommendations offered by experts without accepting them blindly or being inappropriately constrained by them.

Medical Decision-Making Medical decision-making is an important responsibility of the physician and occurs at each stage of the diagnostic and therapeutic process. The decision-making process involves the ordering of additional tests, requests for consultations, and decisions about treatment and predictions concerning prognosis. This process requires an in-depth understanding of the pathophysiology and natural history of disease. As discussed above, medical decision-making should be evidence-based so that patients derive full benefit from the available scientific knowledge. Formulating a differential diagnosis requires not only a broad knowledge base but also the ability to assess the relative probabilities of various diseases. Application of the scientific method, including hypothesis formulation and data collection, is essential to the process of accepting or rejecting a particular diagnosis. Analysis of the differential diagnosis is an iterative process. As new information or test results are acquired, the group of disease processes being considered can be contracted or expanded appropriately.

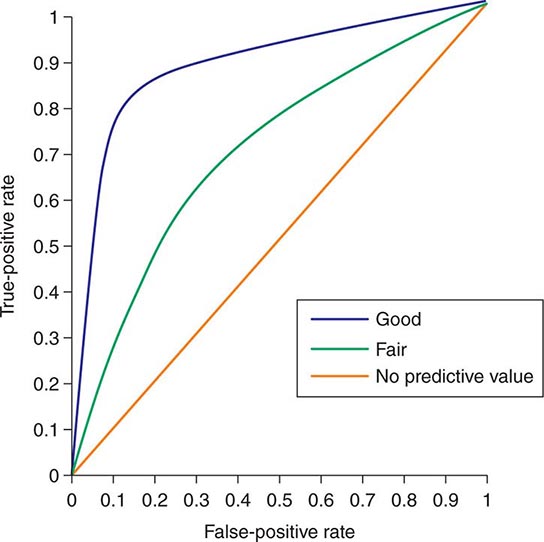

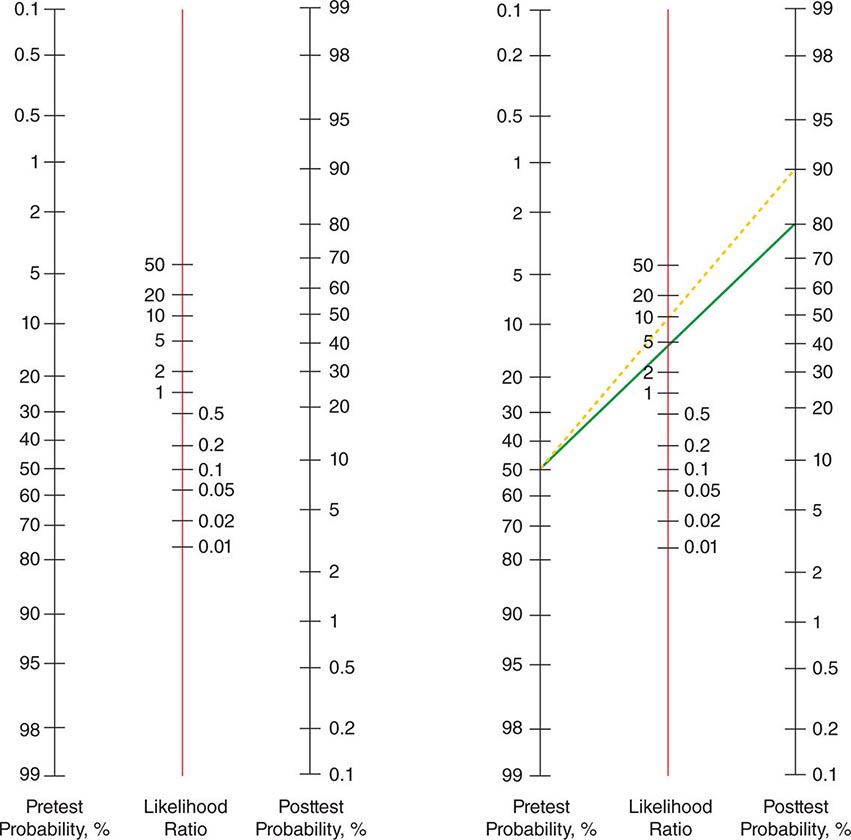

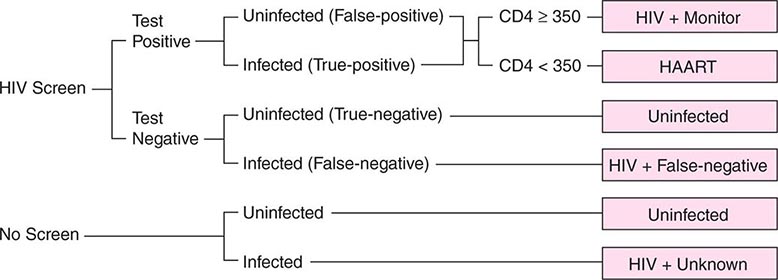

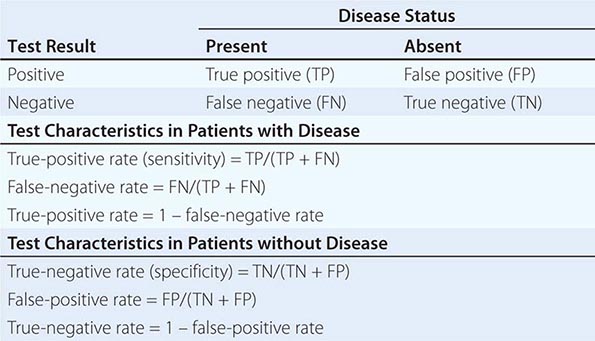

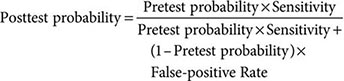

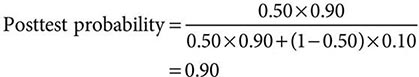

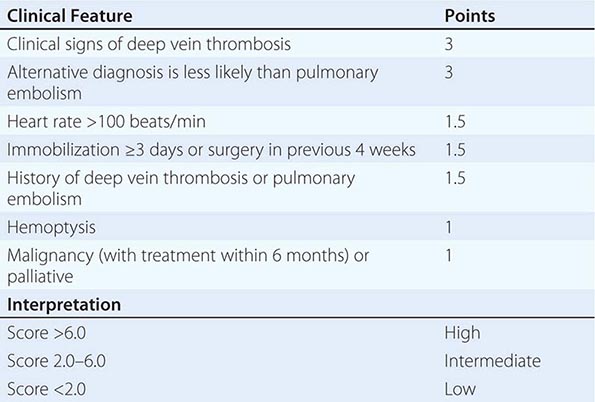

Despite the importance of evidence-based medicine, much medical decision-making relies on good clinical judgment, an attribute that is difficult to quantify or even to assess qualitatively. Physicians must use their knowledge and experience as a basis for weighing known factors, along with the inevitable uncertainties, and then making a sound judgment; this synthesis of information is particularly important when a relevant evidence base is not available. Several quantitative tools may be invaluable in synthesizing the available information, including diagnostic tests, Bayes’ theorem, and multivariate statistical models. Diagnostic tests serve to reduce uncertainty about an individual’s diagnosis or prognosis and help the physician decide how best to manage that individual’s condition. The battery of diagnostic tests complements the history and the physical examination. The accuracy of a particular test is ascertained by determining its sensitivity (true-positive rate) and specificity (true-negative rate) as well as the predictive value of a positive and a negative result. Bayes’ theorem uses information on a test’s sensitivity and specificity, in conjunction with the pretest probability of a diagnosis, to determine mathematically the posttest probability of the diagnosis. More complex clinical problems can be approached with multivariate statistical models, which generate highly accurate information even when multiple factors are acting individually or together to affect disease risk, progression, or response to treatment. Studies comparing the performance of statistical models with that of expert clinicians have documented equivalent accuracy, although the models tend to be more consistent. Thus, multivariate statistical models may be particularly helpful to less experienced clinicians. See Chap. 3 for a more thorough discussion of decision-making in clinical medicine.

Electronic Medical Records Both the growing reliance on computers and the strength of information technology now play central roles in medicine. Laboratory data are accessed almost universally through computers. Many medical centers now have electronic medical records, computerized order entry, and bar-coded tracking of medications. Some of these systems are interactive, sending reminders or warning of potential medical errors.

Electronic medical records offer rapid access to information that is invaluable in enhancing health care quality and patient safety, including relevant data, historical and clinical information, imaging studies, laboratory results, and medication records. These data can be used to monitor and reduce unnecessary variations in care and to provide real-time information about processes of care and clinical outcomes. Ideally, patient records are easily transferred across the health care system. However, technologic limitations and concerns about privacy and cost continue to limit broad-based use of electronic health records in many clinical settings.

As valuable as it is, information technology is merely a tool and can never replace the clinical decisions that are best made by the physician. Clinical knowledge and an understanding of a patient’s needs, supplemented by quantitative tools, still represent the best approach to decision-making in the practice of medicine.

Evaluation of Outcomes Clinicians generally use objective and readily measurable parameters to judge the outcome of a therapeutic intervention. These measures may oversimplify the complexity of a clinical condition as patients often present with a major clinical problem in the context of multiple complicating background illnesses. For example, a patient may present with chest pain and cardiac ischemia, but with a background of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal insufficiency. For this reason, outcome measures such as mortality, length of hospital stay, or readmission rates are typically risk-adjusted. An important point is that patients usually seek medical attention for subjective reasons; they wish to obtain relief from pain, to preserve or regain function, and to enjoy life. The components of a patient’s health status or quality of life can include bodily comfort, capacity for physical activity, personal and professional function, sexual function, cognitive function, and overall perception of health. Each of these important areas can be assessed through structured interviews or specially designed questionnaires. Such assessments provide useful parameters by which a physician can judge patients’ subjective views of their disabilities and responses to treatment, particularly in chronic illness. The practice of medicine requires consideration and integration of both objective and subjective outcomes.

Women’s Health and Disease Although past epidemiologic studies and clinical trials have often focused predominantly on men, more recent studies have included more women, and some, like the Women’s Health Initiative, have exclusively addressed women’s health issues. Significant sex-based differences exist in diseases that afflict both men and women. Much is still to be learned in this arena, and ongoing studies should enhance physicians’ understanding of the mechanisms underlying these differences in the course and outcome of certain diseases. For a more complete discussion of women’s health, see Chap. 6e.

Care of the Elderly The relative proportion of elderly individuals in the populations of developed nations has grown considerably over the past few decades and will continue to grow. The practice of medicine is greatly influenced by the health care needs of this growing demographic group. The physician must understand and appreciate the decline in physiologic reserve associated with aging; the differences in appropriate doses, clearance, and responses to medications; the diminished responses of the elderly to vaccinations such as those against influenza; the different manifestations of common diseases among the elderly; and the disorders that occur commonly with aging, such as depression, dementia, frailty, urinary incontinence, and fractures. For a more complete discussion of medical care for the elderly, see Chap. 11 and Part 5, Chaps. 93e and 94e.

Errors in the Delivery of Health Care A 1999 report from the Institute of Medicine called for an ambitious agenda to reduce medical error rates and improve patient safety by designing and implementing fundamental changes in health care systems. Adverse drug reactions occur in at least 5% of hospitalized patients, and the incidence increases with the use of a large number of drugs. Whatever the clinical situation, it is the physician’s responsibility to use powerful therapeutic measures wisely, with due regard for their beneficial actions, potential dangers, and cost. It is the responsibility of hospitals and health care organizations to develop systems to reduce risk and ensure patient safety. Medication errors can be reduced through the use of ordering systems that rely on electronic processes or, when electronic options are not available, that eliminate misreading of handwriting. Implementation of infection control systems, enforcement of hand-washing protocols, and careful oversight of antibiotic use can minimize the complications of nosocomial infections. Central-line infection rates have been dramatically reduced at many centers by careful adherence of trained personnel to standardized protocols for introducing and maintaining central lines. Rates of surgical infection and wrong-site surgery can likewise be reduced by the use of standardized protocols and checklists. Falls by patients can be minimized by judicious use of sedatives and appropriate assistance with bed-to-chair and bed-to-bathroom transitions. Taken together, these and other measures are saving thousands of lives each year.

The Physician’s Role in Informed Consent The fundamental principles of medical ethics require physicians to act in the patient’s best interest and to respect the patient’s autonomy. These requirements are particularly relevant to the issue of informed consent. Patients are required to sign a consent form for essentially any diagnostic or therapeutic procedure. Most patients possess only limited medical knowledge and must rely on their physicians for advice. Communicating in a clear and understandable manner, physicians must fully discuss the alternatives for care and explain the risks, benefits, and likely consequences of each alternative. In every case, the physician is responsible for ensuring that the patient thoroughly understands these risks and benefits; encouraging questions is an important part of this process. This is the very definition of informed consent. Full, clear explanation and discussion of the proposed procedures and treatment can greatly mitigate the fear of the unknown that commonly accompanies hospitalization. Excellent communication can also help alleviate misunderstandings in situations where complications of intervention occur. Often the patient’s understanding is enhanced by repeatedly discussing the issues in an unthreatening and supportive way, answering new questions that occur to the patient as they arise.

Special care should be taken to ensure that a physician seeking a patient’s informed consent has no real or apparent conflict of interest involving personal gain.

The Approach to Grave Prognoses and Death No circumstance is more distressing than the diagnosis of an incurable disease, particularly when premature death is inevitable. What should the patient and family be told? What measures should be taken to maintain life? What can be done to maintain the quality of life?

Honesty is absolutely essential in the face of a terminal illness. The patient must be given an opportunity to talk with the physician and ask questions. A wise and insightful physician uses such open communication as the basis for assessing what the patient wants to know and when he or she wants to know it. On the basis of the patient’s responses, the physician can assess the right tempo for sharing information. Ultimately, the patient must understand the expected course of the disease so that appropriate plans and preparations can be made. The patient should participate in decision-making with an understanding of the goal of treatment (palliation) and its likely effects. The patient’s religious beliefs must be taken into consideration. Some patients may find it easier to share their feelings about death with their physician, who is likely to be more objective and less emotional, than with family members.

The physician should provide or arrange for emotional, physical, and spiritual support and must be compassionate, unhurried, and open. In many instances, there is much to be gained by the laying on of hands. Pain should be controlled adequately, human dignity maintained, and isolation from family and close friends avoided. These aspects of care tend to be overlooked in hospitals, where the intrusion of life-sustaining equipment can detract from attention to the whole person and encourage concentration instead on the life-threatening disease, against which the battle ultimately will be lost in any case. In the face of terminal illness, the goal of medicine must shift from cure to care in the broadest sense of the term. Primum succurrere, first hasten to help, is a guiding principle. In offering care to a dying patient, a physician must be prepared to provide information to family members and deal with their grief and sometimes their feelings of guilt or even anger. It is important for the doctor to assure the family that everything reasonable has been done. A substantial problem in these discussions is that the physician often does not know how to gauge the prognosis. In addition, various members of the health care team may offer different opinions. Good communication among providers is essential so that consistent information is provided to patients. This is especially important when the best path forward is uncertain. Advice from experts in palliative and terminal care should be sought whenever necessary to ensure that clinicians are not providing patients with unrealistic expectations. For a more complete discussion of end-of-life care, see Chap. 10.

THE PATIENT-PHYSICIAN RELATIONSHIP

The significance of the intimate personal relationship between physician and patient cannot be too strongly emphasized, for in an extraordinarily large number of cases both the diagnosis and treatment are directly dependent on it. One of the essential qualities of the clinician is interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.

—Francis W. Peabody, October 21, 1925,

Lecture at Harvard Medical School

Physicians must never forget that patients are individual human beings with problems that all too often transcend their physical complaints. They are not “cases” or “admissions” or “diseases.” Patients do not fail treatments; treatments fail to benefit patients. This point is particularly important in this era of high technology in clinical medicine. Most patients are anxious and fearful. Physicians should instill confidence and offer reassurance but must never come across as arrogant or patronizing. A professional attitude, coupled with warmth and openness, can do much to alleviate anxiety and to encourage patients to share all aspects of their medical history. Empathy and compassion are the essential features of a caring physician. The physician needs to consider the setting in which an illness occurs—in terms not only of patients themselves but also of their familial, social, and cultural backgrounds. The ideal patient-physician relationship is based on thorough knowledge of the patient, mutual trust, and the ability to communicate.

The Dichotomy of Inpatient and Outpatient Internal Medicine The hospital environment has changed dramatically over the last few decades. Emergency departments and critical care units have evolved to identify and manage critically ill patients, allowing them to survive formerly fatal diseases. At the same time, there is increasing pressure to reduce the length of stay in the hospital and to manage complex disorders in the outpatient setting. This transition has been driven not only by efforts to reduce costs but also by the availability of new outpatient technologies, such as imaging and percutaneous infusion catheters for long-term antibiotics or nutrition, minimally invasive surgical procedures, and evidence that outcomes often are improved by minimizing inpatient hospitalization.

In these circumstances, two important issues arise as physicians cope with the complexities of providing care for hospitalized patients. On the one hand, highly specialized health professionals are essential to the provision of optimal acute care in the hospital; on the other, these professionals—with their diverse training, skills, responsibilities, experiences, languages, and “cultures”—need to work as a team.

In addition to traditional medical beds, hospitals now encompass multiple distinct levels of care, such as the emergency department, procedure rooms, overnight observation units, critical care units, and palliative care units. A consequence of this differentiation has been the emergence of new trends, including specialties (e.g., emergency medicine and end-of-life care) and the provision of in-hospital care by hospitalists and intensivists. Most hospitalists are board-certified internists who bear primary responsibility for the care of hospitalized patients and whose work is limited entirely to the hospital setting. The shortened length of hospital stay that is now standard means that most patients receive only acute care while hospitalized; the increased complexities of inpatient medicine make the presence of a generalist with specific training, skills, and experience in the hospital environment extremely beneficial. Intensivists are board-certified physicians who are further certified in critical care medicine and who direct and provide care for very ill patients in critical care units. Clearly, then, an important challenge in internal medicine today is to ensure the continuity of communication and information flow between a patient’s primary care doctor and these physicians who are in charge of the patient’s hospital care. Maintaining these channels of communication is frequently complicated by patient “handoffs”—i.e., from the outpatient to the inpatient environment, from the critical care unit to a general medicine floor, and from the hospital to the outpatient environment. The involvement of many care providers in conjunction with these transitions can threaten the traditional one-to-one relationship between patient and primary care physician. Of course, patients can benefit greatly from effective collaboration among a number of health care professionals; however, it is the duty of the patient’s principal or primary physician to provide cohesive guidance through an illness. To meet this challenge, primary care physicians must be familiar with the techniques, skills, and objectives of specialist physicians and allied health professionals who care for their patients in the hospital. In addition, primary care doctors must ensure that their patients will benefit from scientific advances and from the expertise of specialists when they are needed both in and out of the hospital. Primary care physicians can also explain the role of these specialists to reassure patients that they are in the hands of the physicians best trained to manage an acute illness. However, the primary care physician should retain ultimate responsibility for making major decisions about diagnosis and treatment and should assure patients and their families that decisions are being made in consultation with these specialists by a physician who has an overall and complete perspective on the case.

A key factor in mitigating the problems associated with multiple care providers is a commitment to interprofessional teamwork. Despite the diversity in training, skills, and responsibilities among health care professionals, common values need to be reinforced if patient care is not to be adversely affected. This component of effective medical care is widely recognized, and several medical schools have integrated interprofessional teamwork into their curricula. The evolving concept of the “medical home” incorporates team-based primary care with linked subspecialty care in a cohesive environment that ensures smooth transitions of care cost-effectively.

Appreciation of the Patient’s Hospital Experience The hospital is an intimidating environment for most individuals. Hospitalized patients find themselves surrounded by air jets, buttons, and glaring lights; invaded by tubes and wires; and beset by the numerous members of the health care team—hospitalists, specialists, nurses, nurses’ aides, physicians’ assistants, social workers, technologists, physical therapists, medical students, house officers, attending and consulting physicians, and many others. They may be transported to special laboratories and imaging facilities replete with blinking lights, strange sounds, and unfamiliar personnel; they may be left unattended at times; and they may be obligated to share a room with other patients who have their own health problems. It is little wonder that a patient’s sense of reality may be compromised. Physicians who appreciate the hospital experience from the patient’s perspective and who make an effort to develop a strong relationship within which they can guide the patient through this experience may make a stressful situation more tolerable.

Trends in the Delivery of Health Care: A Challenge to the Humane Physician Many trends in the delivery of health care tend to make medical care impersonal. These trends, some of which have been mentioned already, include (1) vigorous efforts to reduce the escalating costs of health care; (2) the growing number of managed-care programs, which are intended to reduce costs but in which the patient may have little choice in selecting a physician or in seeing that physician consistently; (3) increasing reliance on technological advances and computerization for many aspects of diagnosis and treatment; and (4) the need for numerous physicians to be involved in the care of most patients who are seriously ill.

In light of these changes in the medical care system, it is a major challenge for physicians to maintain the humane aspects of medical care. The American Board of Internal Medicine, working together with the American College of Physicians–American Society of Internal Medicine and the European Federation of Internal Medicine, has published a Charter on Medical Professionalism that underscores three main principles in physicians’ contract with society: (1) the primacy of patient welfare, (2) patient autonomy, and (3) social justice. While medical schools appropriately place substantial emphasis on professionalism, a physician’s personal attributes, including integrity, respect, and compassion, also are extremely important. Availability to the patient, expression of sincere concern, willingness to take the time to explain all aspects of the illness, and a nonjudgmental attitude when dealing with patients whose cultures, lifestyles, attitudes, and values differ from those of the physician are just a few of the characteristics of a humane physician. Every physician will, at times, be challenged by patients who evoke strongly negative or positive emotional responses. Physicians should be alert to their own reactions to such patients and situations and should consciously monitor and control their behavior so that the patient’s best interest remains the principal motivation for their actions at all times.

An important aspect of patient care involves an appreciation of the patient’s “quality of life,” a subjective assessment of what each patient values most. This assessment requires detailed, sometimes intimate knowledge of the patient, which usually can be obtained only through deliberate, unhurried, and often repeated conversations. Time pressures will always threaten these interactions, but they should not diminish the importance of understanding and seeking to fulfill the priorities of the patient.

EXPANDING FRONTIERS IN MEDICAL PRACTICE

The Era of “Omics”: Genomics, Epigenomics, Proteomics, Microbiomics, Metagenomics, Metabolomics, Exposomics … In the spring of 2003, announcement of the complete sequencing of the human genome officially ushered in the genomic era. However, even before that landmark accomplishment, the practice of medicine had been evolving as a result of the insights into both the human genome and the genomes of a wide variety of microbes. The clinical implications of these insights are illustrated by the complete genome sequencing of H1N1 influenza virus in 2009 and the rapid identification of H1N1 influenza as a potentially fatal pandemic illness, with swift development and dissemination of an effective protective vaccine. Today, gene expression profiles are being used to guide therapy and inform prognosis for a number of diseases, the use of genotyping is providing a new means to assess the risk of certain diseases as well as variations in response to a number of drugs, and physicians are better understanding the role of certain genes in the causality of common conditions such as obesity and allergies. Despite these advances, the use of complex genomics in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of disease is still in its early stages. The task of physicians is complicated by the fact that phenotypes generally are determined not by genes alone but by the interplay of genetic and environmental factors. Indeed, researchers have just begun to scratch the surface of the potential applications of genomics in the practice of medicine.

Rapid progress also is being made in other areas of molecular medicine. Epigenomics is the study of alterations in chromatin and histone proteins and methylation of DNA sequences that influence gene expression. Every cell of the body has identical DNA sequences; the diverse phenotypes a person’s cells manifest are the result of epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Epigenetic alterations are associated with a number of cancers and other diseases. Proteomics, the study of the entire library of proteins made in a cell or organ and its complex relationship to disease, is enhancing the repertoire of the 23,000 genes in the human genome through alternate splicing, posttranslational processing, and posttranslational modifications that often have unique functional consequences. The presence or absence of particular proteins in the circulation or in cells is being explored for diagnostic and disease-screening applications. Microbiomics is the study of the resident microbes in humans and other mammals. The human haploid genome has ~20,000 genes, while the microbes residing on and in the human body comprise over 3–4 million genes; the contributions of these resident microbes are likely to be of great significance with regard to health status. In fact, research is demonstrating that the microbes inhabiting human mucosal and skin surfaces play a critical role in maturation of the immune system, in metabolic balance, and in disease susceptibility. A variety of environmental factors, including the use and overuse of antibiotics, have been tied experimentally to substantial increases in disorders such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, atherosclerosis, and immune-mediated diseases in both adults and children. Metagenomics, of which microbiomics is a part, is the genomic study of environmental species that have the potential to influence human biology directly or indirectly. An example is the study of exposures to microorganisms in farm environments that may be responsible for the lower incidence of asthma among children raised on farms. Metabolomics is the study of the range of metabolites in cells or organs and the ways they are altered in disease states. The aging process itself may leave telltale metabolic footprints that allow the prediction (and possibly the prevention) of organ dysfunction and disease. It seems likely that disease-associated patterns will be sought in lipids, carbohydrates, membranes, mitochondria, and other vital components of cells and tissues. Finally, exposomics refers to efforts to catalogue and capture environmental exposures such as smoking, sunlight, diet, exercise, education, and violence, which together have an enormous impact on health. All of this new information represents a challenge to the traditional reductionist approach to medical thinking. The variability of results in different patients, together with the large number of variables that can be assessed, creates difficulties in identifying preclinical disease and defining disease states unequivocally. Accordingly, the tools of systems biology and network medicine are being applied to the enormous body of information now obtainable for every patient and may eventually provide new approaches to classifying disease. For a more complete discussion of a complex systems approach to human disease, see Chap. 87e.

The rapidity of these advances may seem overwhelming to practicing physicians. However, physicians have an important role to play in ensuring that these powerful technologies and sources of new information are applied with sensitivity and intelligence to the patient. Since “omics” are evolving so rapidly, physicians and other health care professionals must continue to educate themselves so that they can apply this new knowledge to the benefit of their patients’ health and well-being. Genetic testing requires wise counsel based on an understanding of the value and limitations of the tests as well as the implications of their results for specific individuals. For a more complete discussion of genetic testing, see Chap. 84.

The Globalization of Medicine Physicians should be cognizant of diseases and health care services beyond local boundaries. Global travel has implications for disease spread, and it is not uncommon for diseases endemic to certain regions to be seen in other regions after a patient has traveled to and returned from those regions. In addition, factors such as wars, the migration of refugees, and climate change are contributing to changing disease profiles worldwide. Patients have broader access to unique expertise or clinical trials at distant medical centers, and the cost of travel may be offset by the quality of care at those distant locations. As much as any other factor influencing global aspects of medicine, the Internet has transformed the transfer of medical information throughout the world. This change has been accompanied by the transfer of technological skills through telemedicine and international consultation—for example, regarding radiologic images and pathologic specimens. For a complete discussion of global issues, see Chap. 2.

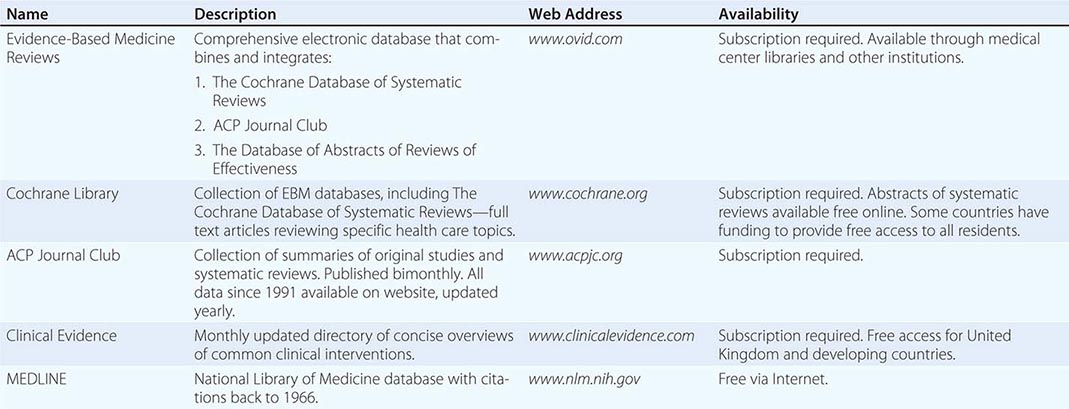

Medicine on the Internet On the whole, the Internet has had a very positive effect on the practice of medicine; through personal computers, a wide range of information is available to physicians and patients almost instantaneously at any time and from anywhere in the world. This medium holds enormous potential for the delivery of current information, practice guidelines, state-of-the-art conferences, journal content, textbooks (including this text), and direct communications with other physicians and specialists, expanding the depth and breadth of information available to the physician regarding the diagnosis and care of patients. Medical journals are now accessible online, providing rapid sources of new information. By bringing them into direct and timely contact with the latest developments in medical care, this medium also serves to lessen the information gap that has hampered physicians and health care providers in remote areas.

Patients, too, are turning to the Internet in increasing numbers to acquire information about their illnesses and therapies and to join Internet-based support groups. Patients often arrive at a clinic visit with sophisticated information about their illnesses. In this regard, physicians are challenged in a positive way to keep abreast of the latest relevant information while serving as an “editor” as patients navigate this seemingly endless source of information, the accuracy and validity of which are not uniform.

A critically important caveat is that virtually anything can be published on the Internet, with easy circumvention of the peer-review process that is an essential feature of academic publications. Both physicians and patients who search the Internet for medical information must be aware of this danger. Notwithstanding this limitation, appropriate use of the Internet is revolutionizing information access for physicians and patients and in this regard represents a remarkable resource that was not available to practitioners a generation ago.

Public Expectations and Accountability The general public’s level of knowledge and sophistication regarding health issues has grown rapidly over the last few decades. As a result, expectations of the health care system in general and of physicians in particular have risen. Physicians are expected to master rapidly advancing fields (the science of medicine) while considering their patients’ unique needs (the art of medicine). Thus, physicians are held accountable not only for the technical aspects of the care they provide but also for their patients’ satisfaction with the delivery and costs of care.

In many parts of the world, physicians increasingly are expected to account for the way in which they practice medicine by meeting certain standards prescribed by federal and local governments. The hospitalization of patients whose health care costs are reimbursed by the government and other third parties is subjected to utilization review. Thus, a physician must defend the cause for and duration of a patient’s hospitalization if it falls outside certain “average” standards. Authorization for reimbursement increasingly is based on documentation of the nature and complexity of an illness, as reflected by recorded elements of the history and physical examination. A growing “pay-for-performance” movement seeks to link reimbursement to quality of care. The goal of this movement is to improve standards of health care and contain spiraling health care costs. In many parts of the United States, managed (capitated) care contracts with insurers have replaced traditional fee-for-service care, placing the onus of managing the cost of all care directly on the providers and increasing the emphasis on preventive strategies. In addition, physicians are expected to give evidence of their current competence through mandatory continuing education, patient record audits, maintenance of certification, and relicensing.

Medical Ethics and New Technologies The rapid pace of technological advance has profound implications for medical applications that go far beyond the traditional goals of disease prevention, treatment, and cure. Cloning, genetic engineering, gene therapy, human–computer interfaces, nanotechnology, and use of designer drugs have the potential to modify inherited predispositions to disease, select desired characteristics in embryos, augment “normal” human performance, replace failing tissues, and substantially prolong life span. Given their unique training, physicians have a responsibility to help shape the debate on the appropriate uses of and limits placed on these new techniques and to consider carefully the ethical issues associated with the implementation of such interventions.

The Physician as Perpetual Student From the time doctors graduate from medical school, it becomes all too apparent that their lot is that of the “perpetual student” and that the mosaic of their knowledge and experiences is eternally unfinished. This realization is at the same time exhilarating and anxiety-provoking. It is exhilarating because doctors can apply constantly expanding knowledge to the treatment of their patients; it is anxiety-provoking because doctors realize that they will never know as much as they want or need to know. Ideally, doctors will translate the latter feeling into energy through which they can continue to improve themselves and reach their potential as physicians. It is the physician’s responsibility to pursue new knowledge continually by reading, attending conferences and courses, and consulting colleagues and the Internet. This is often a difficult task for a busy practitioner; however, a commitment to continued learning is an integral part of being a physician and must be given the highest priority.

The Physician as Citizen Being a physician is a privilege. The capacity to apply one’s skills for the benefit of one’s fellow human beings is a noble calling. The doctor–patient relationship is inherently unbalanced in the distribution of power. In light of their influence, physicians must always be aware of the potential impact of what they do and say and must always strive to strip away individual biases and preferences to find what is best for the patient. To the extent possible, physicians should also act within their communities to promote health and alleviate suffering. Meeting these goals begins by setting a healthy example and continues in taking action to deliver needed care even when personal financial compensation may not be available.

A goal for medicine and its practitioners is to strive to provide the means by which the poor can cease to be unwell.

Learning Medicine It has been a century since the publication of the Flexner Report, a seminal study that transformed medical education and emphasized the scientific foundations of medicine as well as the acquisition of clinical skills. In an era of burgeoning information and access to medical simulation and informatics, many schools are implementing new curricula that emphasize lifelong learning and the acquisition of competencies in teamwork, communication skills, system-based practice, and professionalism. These and other features of the medical school curriculum provide the foundation for many of the themes highlighted in this chapter and are expected to allow physicians to progress, with experience and learning over time, from competency to proficiency to mastery.

At a time when the amount of information that must be mastered to practice medicine continues to expand, increasing pressures both within and outside of medicine have led to the implementation of restrictions on the amount of time a physician-in-training can spend in the hospital. Because the benefits associated with continuity of medical care and observation of a patient’s progress over time were thought to be outstripped by the stresses imposed on trainees by long hours and by the fatigue-related errors they made in caring for patients, strict limits were set on the number of patients that trainees could be responsible for at one time, the number of new patients they could evaluate in a day on call, and the number of hours they could spend in the hospital. In 1980, residents in medicine worked in the hospital more than 90 hours per week on average. In 1989, their hours were restricted to no more than 80 per week. Resident physicians’ hours further decreased by ~10% between 1996 and 2008, and in 2010 the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education further restricted (i.e., to 16 hours per shift) consecutive in-hospital duty hours for first-year residents. The impact of these changes is still being assessed, but the evidence that medical errors have decreased as a consequence is sparse. An unavoidable by-product of fewer hours at work is an increase in the number of “handoffs” of patient responsibility from one physician to another. These transfers often involve a transition from a physician who knows the patient well, having evaluated that individual on admission, to a physician who knows the patient less well. It is imperative that these transitions of responsibility be handled with care and thoroughness, with all relevant information exchanged and acknowledged.

Research, Teaching, and the Practice of Medicine The word doctor is derived from the Latin docere, “to teach.” As teachers, physicians should share information and medical knowledge with colleagues, students of medicine and related professions, and their patients. The practice of medicine is dependent on the sum total of medical knowledge, which in turn is based on an unending chain of scientific discovery, clinical observation, analysis, and interpretation. Advances in medicine depend on the acquisition of new information through research, and improved medical care requires the transmission of that information. As part of their broader societal responsibilities, physicians should encourage patients to participate in ethical and properly approved clinical investigations if these studies do not impose undue hazard, discomfort, or inconvenience. However, physicians engaged in clinical research must be alert to potential conflicts of interest between their research goals and their obligations to individual patients. The best interests of the patient must always take priority.

To wrest from nature the secrets which have perplexed philosophers in all ages, to track to their sources the causes of disease, to correlate the vast stores of knowledge, that they may be quickly available for the prevention and cure of disease—these are our ambitions.

—William Osler, 1849–1919

2 |

Global Issues in Medicine |

WHY GLOBAL HEALTH?

Global health is not a discipline; it is, rather, a collection of problems. Some scholars have defined global health as the field of study and practice concerned with improving the health of all people and achieving health equity worldwide, with an emphasis on addressing transnational problems. No single review can do much more than identify the leading problems in applying evidence-based medicine in settings of great poverty or across national boundaries. However, this is a moment of opportunity: only recently, persistent epidemics, improved metrics, and growing interest have been matched by an unprecedented investment in addressing the health problems of poor people in the developing world. To ensure that this opportunity is not wasted, the facts need to be laid out for specialists and laypeople alike. This chapter introduces the major international bodies that address health problems; identifies the more significant barriers to improving the health of people who to date have not, by and large, had access to modern medicine; and summarizes population-based data on the most common health problems faced by people living in poverty. Examining specific problems—notably HIV/AIDS (Chap. 226) but also tuberculosis (TB, Chap. 202), malaria (Chap. 248), and key “noncommunicable” chronic diseases (NCDs)—helps sharpen the discussion of barriers to prevention, diagnosis, and care as well as the means of overcoming them. This chapter closes by discussing global health equity, drawing on notions of social justice that once were central to international public health but had fallen out of favor during the last decades of the twentieth century.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF GLOBAL HEALTH INSTITUTIONS

Concern about health across national boundaries dates back many centuries, predating the Black Plague and other pandemics. One of the first organizations founded explicitly to tackle cross-border health issues was the Pan American Sanitary Bureau, which was formed in 1902 by 11 countries in the Americas. The primary goal of what later became the Pan American Health Organization was the control of infectious diseases across the Americas. Of special concern was yellow fever, which had been running a deadly course through much of South and Central America and halted the construction of the Panama Canal. In 1948, the United Nations formed the first truly global health institution: the World Health Organization (WHO). In 1958, under the aegis of the WHO and in line with a long-standing focus on communicable diseases that cross borders, leaders in global health initiated the effort that led to what some see as the greatest success in international health: the eradication of smallpox. Naysayers were surprised when the smallpox eradication campaign, which engaged public health officials throughout the world, proved successful in 1979 despite the ongoing Cold War.

At the International Conference on Primary Health Care in Alma-Ata (in what is now Kazakhstan) in 1978, public health officials from around the world agreed on a commitment to “Health for All by the Year 2000,” a goal to be achieved by providing universal access to primary health care worldwide. Critics argued that the attainment of this goal by the proposed date was impossible. In the ensuing years, a strategy for the provision of selective primary health care emerged that included four inexpensive interventions collectively known as GOBI: growth monitoring, oral rehydration, breast-feeding, and immunizations for diphtheria, whooping cough, tetanus, polio, TB, and measles. GOBI later was expanded to GOBI-FFF, which also included female education, food, and family planning. Some public health figures saw GOBI-FFF as an interim strategy to achieve “health for all,” but others criticized it as a retreat from the bolder commitments of Alma-Ata.

The influence of the WHO waned during the 1980s. In the early 1990s, many observers argued that, with its vastly superior financial resources and its close—if unequal—relationships with the governments of poor countries, the World Bank had eclipsed the WHO as the most important multilateral institution working in the area of health. One of the stated goals of the World Bank was to help poor countries identify “cost-effective” interventions worthy of public funding and international support. At the same time, the World Bank encouraged many of those nations to reduce public expenditures in health and education in order to stimulate economic growth as part of (later discredited) structural adjustment programs whose restrictions were imposed as a condition for access to credit and assistance through international financial institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. There was a resurgence of many diseases, including malaria, trypanosomiasis, and schistosomiasis, in Africa. TB, an eminently curable disease, remained the world’s leading infectious killer of adults. Half a million women per year died in childbirth during the last decade of the twentieth century, and few of the world’s largest philanthropic or funding institutions focused on global health equity.

HIV/AIDS, first described in 1981, precipitated a change. In the United States, the advent of this newly described infectious killer marked the culmination of a series of events that discredited talk of “closing the book” on infectious diseases. In Africa, which would emerge as the global epicenter of the pandemic, HIV disease strained TB control programs, and malaria continued to take as many lives as ever. At the dawn of the twenty-first century, these three diseases alone killed nearly 6 million people each year. New research, new policies, and new funding mechanisms were called for. The past decade has seen the rise of important multilateral global health financing institutions such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria; bilateral efforts such as the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR); and private philanthropic organizations such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. With its 193 member states and 147 country offices, the WHO remains important in matters relating to the cross-border spread of infectious diseases and other health threats. In the aftermath of the epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2003, the WHO’s International Health Regulations—which provide a legal foundation for that organization’s direct investigation into a wide range of global health problems, including pandemic influenza, in any member state—were strengthened and brought into force in May 2007.

Even as attention to and resources for health problems in poor countries grow, the lack of coherence in and among global health institutions may undermine efforts to forge a more comprehensive and effective response. The WHO remains underfunded despite the ever-growing need to engage a wider and more complex range of health issues. In another instance of the paradoxical impact of success, the rapid growth of the Gates Foundation, which is one of the most important developments in the history of global health, has led some foundations to question the wisdom of continuing to invest their more modest resources in this field. This indeed may be what some have called “the golden age of global health,” but leaders of major organizations such as the WHO, the Global Fund, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), PEPFAR, and the Gates Foundation must work together to design an effective architecture that will make the most of opportunities to link new resources for and commitments to global health equity with the emerging understanding of disease burden and unmet need. To this end, new and old players in global health must invest heavily in discovery (relevant basic science), development of new tools (preventive, diagnostic, and therapeutic), and modes of delivery that will ensure the equitable provision of health products and services to all who need them.

THE ECONOMICS OF GLOBAL HEALTH

Political and economic concerns have often guided global health interventions. As mentioned, early efforts to control yellow fever were tied to the completion of the Panama Canal. However, the precise nature of the link between economics and health remains a matter for debate. Some economists and demographers argue that improving the health status of populations must begin with economic development; others maintain that addressing ill health is the starting point for development in poor countries. In either case, investment in health care, especially the control of communicable diseases, should lead to increased productivity. The question is where to find the necessary resources to start the predicted “virtuous cycle.”

During the past two decades, spending on health in poor countries has increased dramatically. According to a study from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington, total development assistance for health worldwide grew to $28.2 billion in 2010—up from $5.6 billion in 1990. In 2010, the leading contributors included U.S. bilateral agencies such as PEPFAR, the Global Fund, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), the WHO, the World Bank, and the Gates Foundation. It appears, however, that total development assistance for health plateaued in 2010, and it is unclear whether growth will continue in the upcoming decade.

To reach the United Nations Millennium Development Goals, which include targets for poverty reduction, universal primary education, and gender equality, spending in the health sector must be increased above the 2010 levels. To determine by how much and for how long, it is imperative to improve the ability to assess the global burden of disease and to plan interventions that more precisely match need.

MORTALITY AND THE GLOBAL BURDEN OF DISEASE

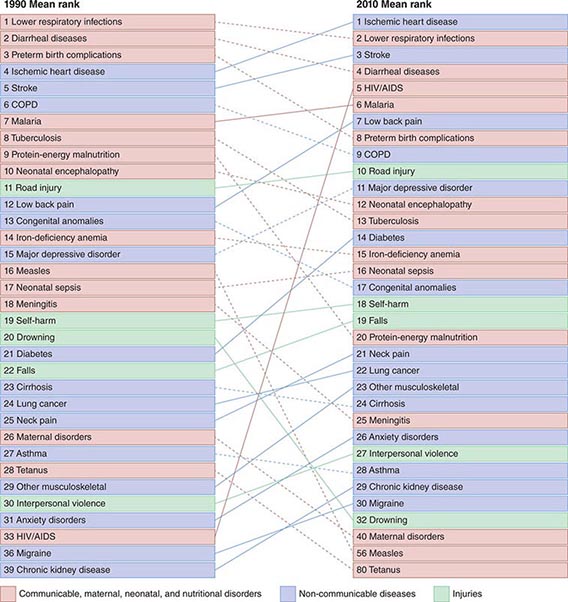

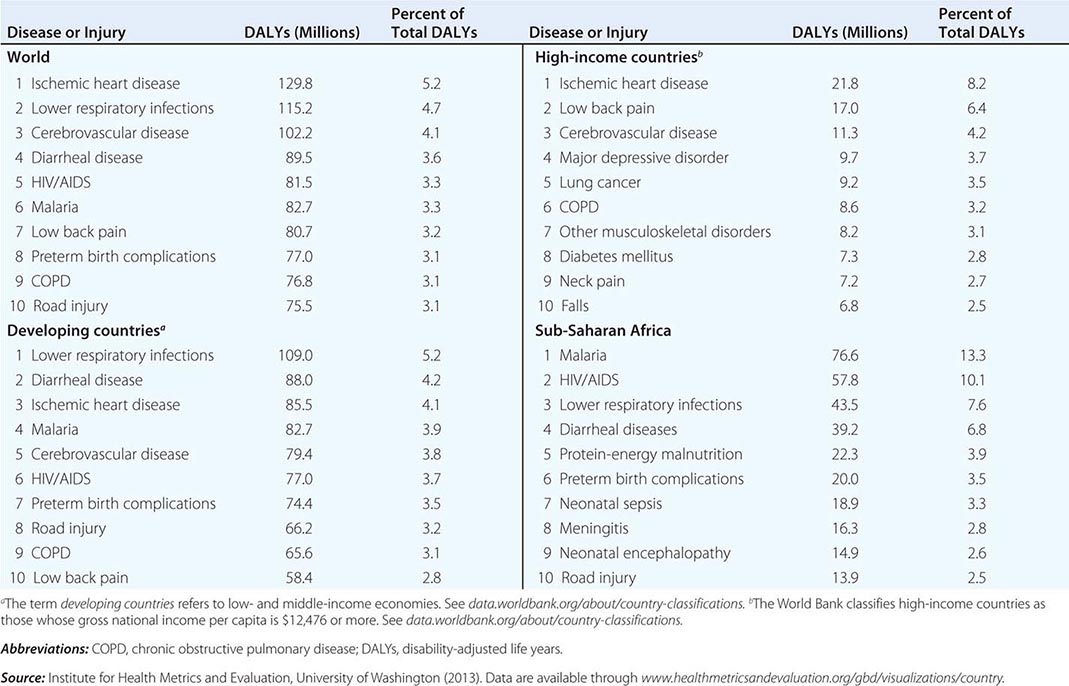

Refining metrics is an important task for global health: only recently have there been solid assessments of the global burden of disease. The first study to look seriously at this issue, conducted in 1990, laid the foundation for the first report on Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries and for the World Bank’s 1993 World Development Report Investing in Health. Those efforts represented a major advance in the understanding of health status in developing countries. Investing in Health has been especially influential: it familiarized a broad audience with cost-effectiveness analysis for specific health interventions and with the notion of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). The DALY, which has become a standard measure of the impact of a specific health condition on a population, combines absolute years of life lost and years lost due to disability for incident cases of a condition. (See Fig. 2-1 and Table 2-1 for an analysis of the global disease burden by DALYs.)

FIGURE 2-1 Global DALY (disability-adjusted life year) ranks for the top causes of disease burden in 1990 and 2010. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. (Reproduced with permission from C Murray et al: Disability-adjusted life years [DALYs] for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380:2197–2223, 2012.)

|

LEADING CAUSES OF DISEASE BURDEN, 2010 |

In 2012, the IHME and partner institutions began publishing results from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2010 (GBD 2010). GBD 2010 is the most comprehensive effort to date to produce longitudinal, globally complete, and comparable estimates of the burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. This report reflects the expansion of the available data on health in the poorest countries and of the capacity to quantify the impact of specific conditions on a population. It measures current levels and recent trends in all major diseases, injuries, and risk factors among 21 regions and for 20 age groups and both sexes. The GBD 2010 team revised and improved the health-state severity weight system, collated published data, and used household surveys to enhance the breadth and accuracy of disease burden data. As analytic methods and data quality improve, important trends can be identified in a comparison of global disease burden estimates from 1990 to 2010.

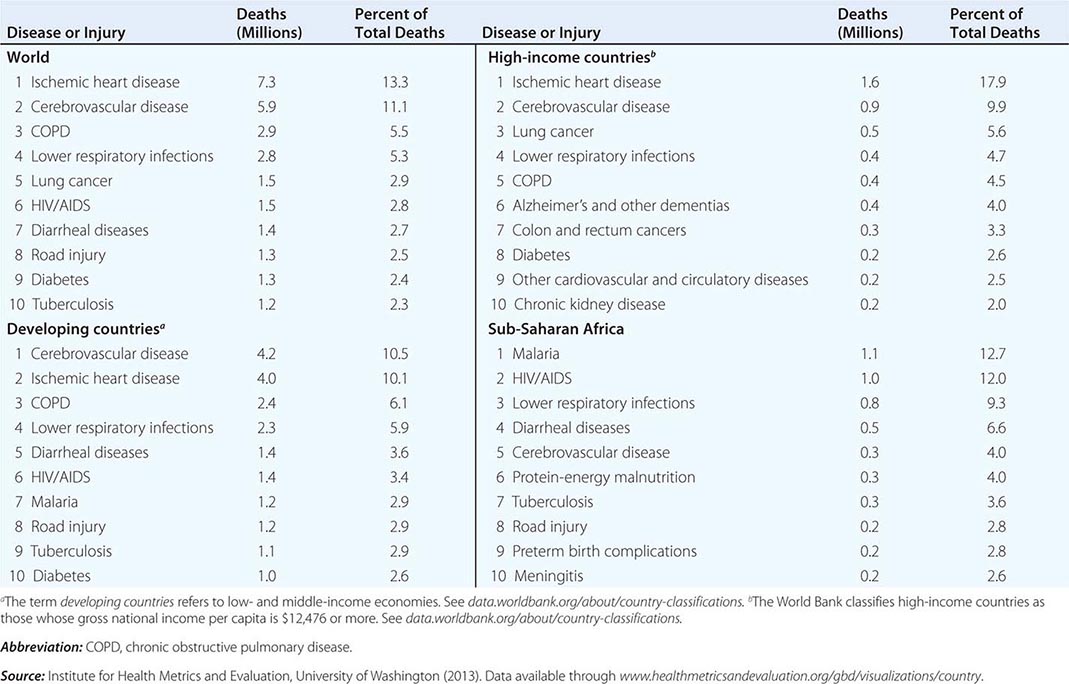

GLOBAL MORTALITY

Of the 52.8 million deaths worldwide in 2010, 24.6% (13 million) were due to communicable diseases, maternal and perinatal conditions, and nutritional deficiencies—a marked decrease compared with figures for 1990, when these conditions accounted for 34% of global mortality. Among the fraction of all deaths related to communicable diseases, maternal and perinatal conditions, and nutritional deficiencies, 76% occurred in sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia. While the proportion of deaths due to these conditions has decreased significantly in the past decade, there has been a dramatic rise in the number of deaths from NCDs, which constituted the top five causes of death in 2010. The leading cause of death among adults in 2010 was ischemic heart disease, accounting for 7.3 million deaths (13.8% of total deaths) worldwide. In high-income countries ischemic heart disease accounted for 17.9% of total deaths, and in developing (low- and middle-income) countries it accounted for 10.1%. It is noteworthy that ischemic heart disease was responsible for just 2.6% of total deaths in sub-Saharan Africa (Table 2-2). In second place—causing 11.1% of global mortality—was cerebrovascular disease, which accounted for 9.9% of deaths in high-income countries, 10.5% in developing countries, and 4.0% in sub-Saharan Africa. Although the third leading cause of death in high-income countries was lung cancer (accounting for 5.6% of all deaths), this condition did not figure among the top 10 causes in low- and middle-income countries. Among the 10 leading causes of death in sub-Saharan Africa, 6 were infectious diseases, with malaria and HIV/AIDS ranking as the dominant contributors to disease burden. In high-income countries, however, only one infectious disease—lower respiratory infection—ranked among the top 10 causes of death.

|

LEADING CAUSES OF DEATH WORLDWIDE, 2010 |

The GBD 2010 found that the worldwide mortality figure among children <5 years of age dropped from 16.39 million in 1970 to 11.9 million in 1990 and to 6.8 million in 2010—a decrease that surpassed predictions. Of childhood deaths in 2010, 3.1 million (40%) occurred in the neonatal period. About one-third of deaths among children <5 years old occurred in southern Asia and almost one-half in sub-Saharan Africa; <1% occurred in high-income countries.

The global burden of death due to HIV/AIDS and malaria was on an upward slope until 2004; significant improvements have since been documented. Global deaths from HIV infection fell from 1.7 million in 2006 to 1.5 million in 2010, while malaria deaths dropped from 1.2 million to 0.98 million over the same period. Despite these improvements, malaria and HIV/AIDS continue to be major burdens in particular regions, with global implications. Although it has a minor impact on mortality outside sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, malaria is the eleventh leading cause of death worldwide. HIV infection ranked thirty-third in global DALYs in 1990 but was the fifth leading cause of disease burden in 2010, with sub-Saharan Africa bearing the vast majority of this burden (Fig. 2-1).

The world’s population is living longer: global life expectancy has increased significantly over the past 40 years from 58.8 years in 1970 to 70.4 years in 2010. This demographic change, accompanied by the fact that the prevalence of NCDs increases with age, is dramatically shifting the burden of disease toward NCDs, which have surpassed communicable, maternal, nutritional, and neonatal causes. By 2010, 65.5% of total deaths at all ages and 54% of all DALYs were due to NCDs. Increasingly, the global burden of disease comprises conditions and injuries that cause disability rather than death.

Worldwide, although both life expectancy and years of life lived in good health have risen, years of life lived with disability have also increased. Despite the higher prevalence of diseases common in older populations (e.g., dementia and musculoskeletal disease) in developed and high-income countries, best estimates from 2010 reveal that disability resulting from cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, and the long-term impact of communicable diseases was greater in low- and middle-income countries. In most developing countries, people lived shorter lives and experienced disability and poor health for a greater proportion of their lives. Indeed, 50% of the global burden of disease occurred in southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, which together account for only 35% of the world’s population.

HEALTH AND WEALTH

Clear disparities in burden of disease (both communicable and noncommunicable) across country income levels are strong indicators that poverty and health are inherently linked. Poverty remains one of the most important root causes of poor health worldwide, and the global burden of poverty continues to be high. Among the 6.7 billion people alive in 2008, 19% (1.29 billion) lived on less than $1.25 a day—one standard measurement of extreme poverty—and another 1.18 billion lived on $1.25 to $2 a day. Approximately 600 million children—more than 30% of those in low-income countries—lived in extreme poverty in 2005. Comparison of national health indicators with gross domestic product per capita among nations shows a clear relationship between higher gross domestic product and better health, with only a few outliers. Numerous studies have also documented the link between poverty and health within nations as well as across them.

RISK FACTORS FOR DISEASE BURDEN

The GBD 2010 study found that the three leading risk factors for global disease burden in 2010 were (in order of frequency) high blood pressure, tobacco smoking (including secondhand smoke), and alcohol use—a substantial change from 1990, when childhood undernutrition was ranked first. Though ranking eighth in 2010, childhood undernutrition remains the leading risk factor for death worldwide among children <5 years of age. In an era that has seen obesity become a major health concern in many developed countries—and the sixth leading risk factor worldwide—the persistence of undernutrition is surely cause for great consternation. Low body weight is still the dominant risk factor for disease burden in sub-Saharan Africa. Inability to feed the hungry reflects many years of failed development projects and must be addressed as a problem of the highest priority. Indeed, no health care initiative, however generously funded, will be effective without adequate nutrition.

In a 2006 publication that examined how specific diseases and injuries are affected by environmental risk, the WHO estimated that roughly one-quarter of the total global burden of disease, one-third of the global disease burden among children, and 23% of all deaths were due to modifiable environmental factors. Many of these factors lead to deaths from infectious diseases; others lead to deaths from malignancies. Etiology and nosology are increasingly difficult to parse. As much as 94% of diarrheal disease, which is linked to unsafe drinking water and poor sanitation, can be attributed to environmental factors. Risk factors such as indoor air pollution due to use of solid fuels, exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke, and outdoor air pollution account for 20% of lower respiratory infections in developed countries and for as many as 42% of such infections in developing countries. Various forms of unintentional injury and malaria top the list of health problems to which environmental factors contribute. Some 4 million children die every year from causes related to unhealthy environments, and the number of infant deaths due to environmental factors in developing countries is 12 times that in developed countries.

The second edition of Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries, published in 2006, is a document of great breadth and ambition, providing cost-effectiveness analyses for more than 100 interventions and including 21 chapters focused on strategies for strengthening health systems. Cost-effectiveness analyses that compare relatively equivalent interventions and facilitate the best choices under constraint are necessary; however, these analyses are often based on an incomplete knowledge of cost and evolving evidence of effectiveness. As both resources and objectives for global health grow, cost-effectiveness analyses (particularly those based on older evidence) must not hobble the increased worldwide commitment to providing resources and accessible health care services to all who need them. This is why we use the term global health equity. To illustrate these points, it is instructive to look to HIV/AIDS, which in the course of the last three decades has become the world’s leading infectious cause of adult death.

HIV INFECTION/AIDS

Chapter 226 provides an overview of the HIV epidemic in the world today. Here the discussion will be limited to HIV/AIDS in the developing world. Lessons learned from tackling HIV/AIDS in resource-constrained settings are highly relevant to discussions of other chronic diseases, including NCDs, for which effective therapies have been developed.

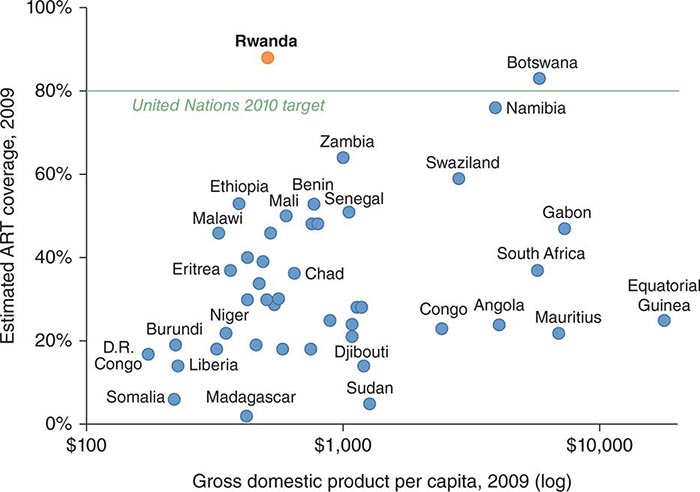

Approximately 34 million people in all countries worldwide were living with HIV infection in 2011; more than 8 million of those in low- and middle-income countries were receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART)—a number representing a 20-fold increase over the corresponding figure for 2003. By the end of 2011, 54% of people eligible for treatment were receiving ART. (It remains to be seen how many of these people are receiving ART regularly and with the requisite social support.)