21 Darker skin types

Summary and Key Features

• Botulinum toxin is a safe and effective procedure in darker skin types

• In general, efficacy and safety profiles are similar to lighter skin types

• With appropriate use, side effects are uncommon

• Injection techniques are similar to lighter skin types

• Commonly treated areas are glabellar and horizontal forehead lines

Safety and efficacy of botulinum toxins in darker skin types

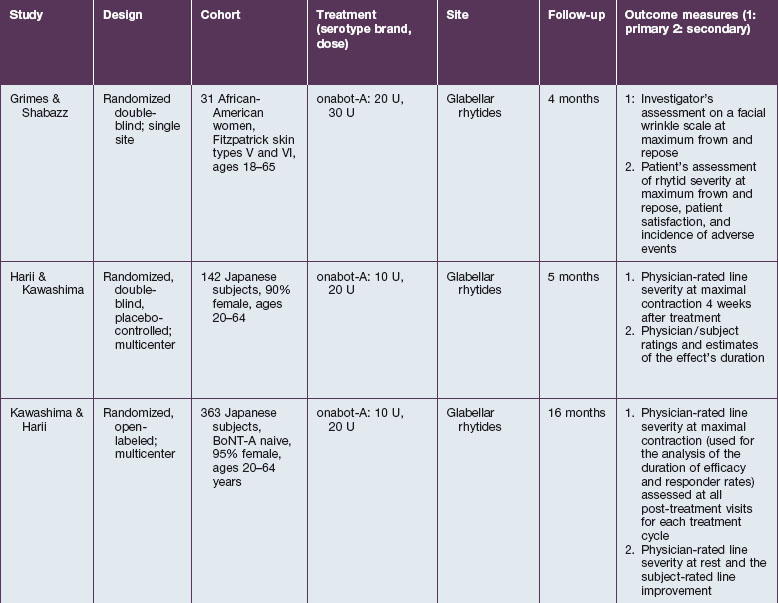

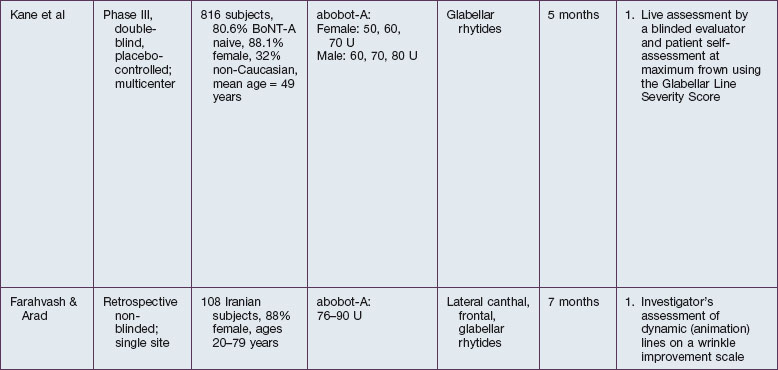

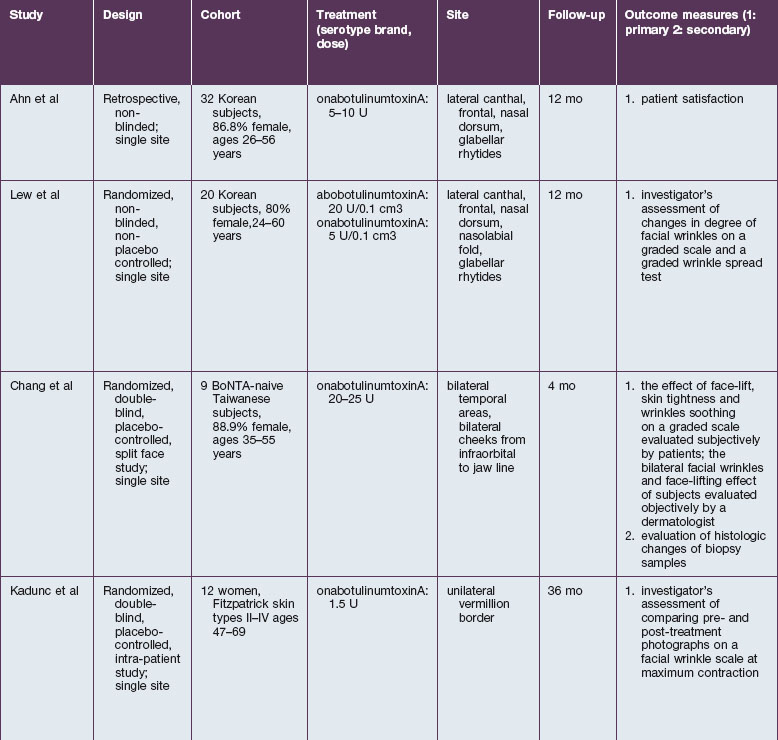

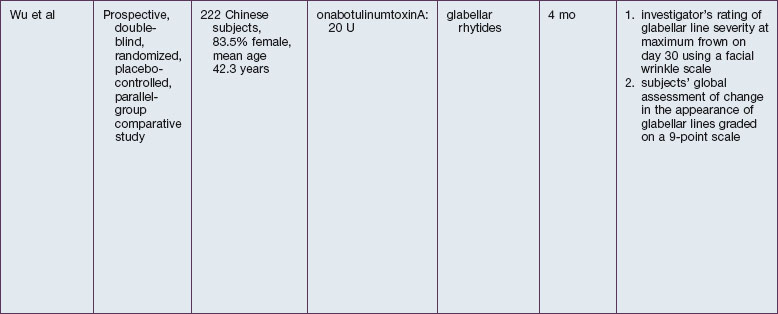

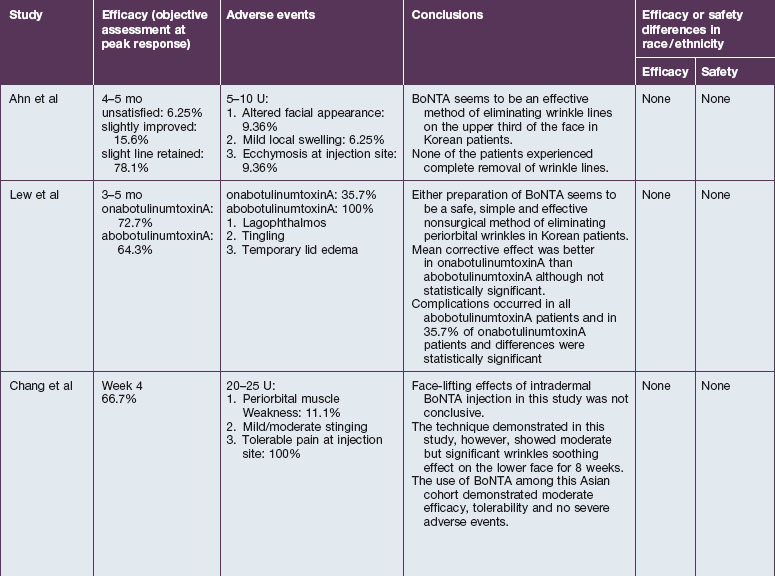

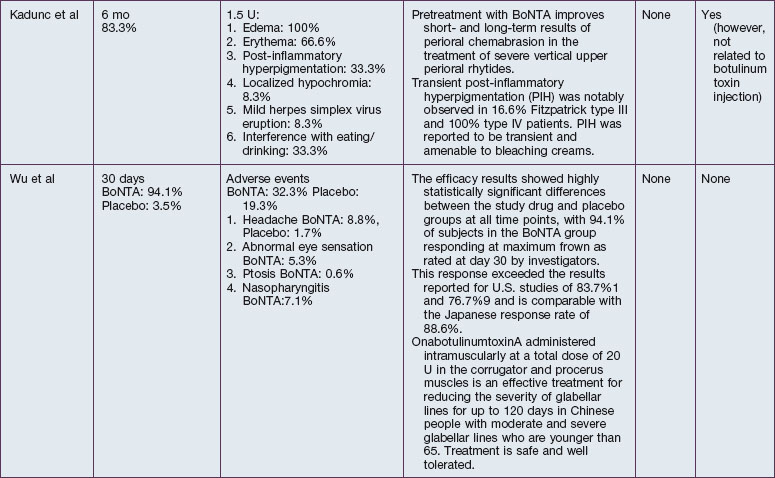

The safety and efficacy of botulinum neurotoxin type A in the treatment of glabellar lines has been well studied in numerous populations (Table 21.1). Published data pertaining to the safety and efficacy of botulinum toxin in non-white patient populations are reviewed herein.

African-Americans

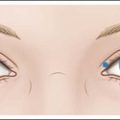

Grimes & Shabazz conducted a Phase IV study of onabot-A in the treatment of glabellar lines in 31 African-American women with Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI. The authors assessed the safety and efficacy at doses of 20 and 30 units (U) of onabot-A. No statistically significant differences in efficacy or safety were observed between the two doses (Figs 21.1, 21.2). A maximal response was observed on day 30, with 92.4% and 100% response rates (i.e. a score of ‘none’ or ‘mild’ on the facial wrinkle scale) in the 20 U and 30 U groups respectively. Adverse events were mild and transient and did not differ between the dosing groups. They included mild tingling, slight headaches, and dullness of the forehead.

Pearl 1

Appropriate magnification of injection sites is important to avoid vessels in darker skin types.

Ahn J, Horn C, Blitzer A. Botulinum toxin for masseter reduction in Asian patients. Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery. 2004;6(3):188–191.

Ahn KY, Park MY, Park DH, et al. Botulinum toxin A for the treatment of facial hyperkinetic wrinkle lines in Koreans. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2000;105(2):778–784.

Carruthers JD, Glogau RG, Blitzer A. Advances in facial rejuvenation: botulinum toxin type a, hyaluronic acid dermal fillers, and combination therapies – consensus recommendations. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2008;121(5 suppl):S5–S30. quiz S31–S36

Carruthers JA, Lowe NJ, Menter MA, et al. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of glabellar lines. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2002;46(6):840–849.

Chang SP, Tsai HH, Chen WY, et al. The wrinkles soothing effect on the middle and lower face by intradermal injection of botulinum toxin type A. International Journal of Dermatology. 2008;47(12):1287–1294.

Davis EC, Callender VD. Aesthetic dermatology for aging ethnic skin. Dermatologic Surgery. 2011;37(7):901–917.

Flynn TC. Periocular botulinum toxin. Clinical Dermatology. 2003;21(6):498–504.

Flynn TC, Carruthers JA. Botulinum-A toxin treatment of the lower eyelid improves infraorbital rhytides and widens the eye. Dermatologic Surgery. 2001;27(8):703–708.

Grimes P. Skin of color. Diseases and cosmetic issues of major concern. Cosmetic Dermatology. 2003;16:1–4.

Grimes PE, ed. Aesthetics and Cosmetic Surgery for Darker Skin Types, 1st edn, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.

Grimes PE, Shabazz D. A four-month randomized, double-blind evaluation of the efficacy of botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of glabellar lines in women with skin types V and VI. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35(3):429–436.

Han KH, Joo YH, Moon SE, et al. Botulinum toxin A treatment for contouring of the lower leg. Journal of Dermatologic Treatment. 2006;17(4):250–254.

Harii K, Kawashima M. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, two-dose comparative study of botulinum toxin type A for treating glabellar lines in Japanese subjects. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2008;32(5):724–730.

Harris MO. The aging face in patients of color: minimally invasive surgical facial rejuvenation – a targeted approach. Dermatologic Therapy. 2004;17(2):206–211.

Hexsel DM, Hexsel CL, Brunetto LT. Botulinum toxin. In: Grimes PE, ed. Aesthetics and Cosmetic Surgery for Darker Skin Types. 1st edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:214–215.

Kadunc BV, Trindade DEAAR, Vanti AA, et al. Botulinum toxin A adjunctive use in manual chemabrasion: controlled long-term study for treatment of upper perioral vertical wrinkles. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33(9):1066–1072. discussion 1072

Kaidbey KH, Agin PP, Sayre RM, et al. Photoprotection by melanin – a comparison of black and Caucasian skin. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1979;1(3):249–260.

Kane MA, Brandt F, Rohrich RJ, et al. Evaluation of variable-dose treatment with a new U.S. botulinum toxin type A (Dysport) for correction of moderate to severe glabellar lines: results from a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2009;124(5):1619–1629.

Kawashima M, Harii K. An open-label, randomized, 64-week study repeating 10- and 20-U doses of botulinum toxin type A for treatment of glabellar lines in Japanese subjects. International Journal of Dermatology. 2009;48(7):768–776.

Kim NH, Park RH, Park JB. Botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of hypertrophy of the masseter muscle. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2010;125(6):1693–1705.

Lee HJ, Lee DW, Park YH, et al. Botulinum toxin a for aesthetic contouring of enlarged medial gastrocnemius muscle. Dermatologic Surgery. 2004;30(6):867–871. discussion 871

Lew H, Yun YS, Lee SY, et al. Effect of botulinum toxin A on facial wrinkle lines in Koreans. Ophthalmologica. 2002;216(1):50–54.

McKnight A, Momoh AO, Bullocks JM. Variations of structural components: specific intercultural differences in facial morphology, skin type, and structures. Seminars in Plastic Surgery. 2009;23(3):163–167.

Nouveau-Richard S, Yang Z, Mac-Mary S, et al. Skin ageing: a comparison between Chinese and European populations. A pilot study. Journal of Dermatologic Science. 2005;40(3):187–193.

Rossi A, Alexis A. Cosmetic procedures in skin of color. Giornale Italiano di Dermatologia e Venereologia. 2011;146(4):265–272.

Yamaguchi Y, Beer JZ, Hearing VJ. Melanin mediated apoptosis of epidermal cells damaged by ultraviolet radiation: factors influencing the incidence of skin cancer. Archives of Dermatological Research. 2008;300(suppl 1):S43–S50.