D

δ wave, see Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome

DA examination (Diploma in Anaesthetics). First specialist examination in anaesthetics; first held in 1935 in London. Originally intended for anaesthetists with at least 2 years’ experience and 2000 anaesthetics, later reduced to 1 year’s residence in an approved hospital. A two-part examination was introduced in 1947, becoming the FFARCS examination in 1953; the single-part DA remained separate until 1984, when the DA (UK) became the first part of the new three-part FFARCS. Replaced by the new FRCA examination in 1996.

Dabigatran etexilate. Direct thrombin inhibitor, preventing the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin; thus impairs coagulation and platelet activation. Prolongs the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT). A prodrug, rapidly metabolised to active metabolite (dabigatran) by non-specific esterases; oral bioavailability is 6.5%. Onset of action is 0.5–2 h, with steady state achieved within 3 days. 80% of drug is renally excreted unchanged; half-life is 8–14 h, increased to > 24 h in severe renal failure. Also metabolised by the liver and excreted in the bile.

Licensed for DVT prophylaxis in adults undergoing total knee or hip replacement surgery, and for prevention of CVA in patients with AF with certain risk factors. Under investigation for the treatment of DVT and acute coronary syndrome. Developed as an alternative to warfarin, over which it has several advantages:

no therapeutic monitoring required.

no therapeutic monitoring required.

fixed dosage (modified according to age, indication, renal function and drug interactions).

fixed dosage (modified according to age, indication, renal function and drug interactions).

faster onset and shorter duration of action.

faster onset and shorter duration of action.

stable, predictable pharmacokinetics, with fewer drug interactions.

stable, predictable pharmacokinetics, with fewer drug interactions.

Disadvantages include: higher cost; no specific antidote in case of overdose (although can be removed by dialysis); unsuitable for patients with severe renal impairment (GFR < 30 ml/min).

• Dosage:

CVA prophylaxis in patients with AF: 150 mg orally bd, reduced to 75 mg in renal impairment.

CVA prophylaxis in patients with AF: 150 mg orally bd, reduced to 75 mg in renal impairment.

• Drug interactions: potentiated by concomitant verapamil and amiodarone; reduced dosing regimen is used. Inhibited by rifampicin, ketoconazole and quinidine.

Main side effect is bleeding; risk is similar or lower than equivalent treatment with warfarin.

Dalteparin sodium, see Heparin

Damage control resuscitation. Approach to major trauma, developed in modern military settings. Aims to reduce the incidence and severity of the combination of acute coagulopathy, hypothermia and metabolic acidosis that commonly accompany major haemorrhage. Consists of:

‘permissive hypotension’: restricted fluid resuscitation to maintain a radial pulse rather than a normal or near-normal BP, accepting a period of organ hypoperfusion (except in head injury, where maintenance of cerebral perfusion pressure is thought to be vital).

‘permissive hypotension’: restricted fluid resuscitation to maintain a radial pulse rather than a normal or near-normal BP, accepting a period of organ hypoperfusion (except in head injury, where maintenance of cerebral perfusion pressure is thought to be vital).

‘haemostatic resuscitation’: early use of blood products to prevent/treat acute coagulopathy, including platelets (in a 1:1 ratio with packed red cells [1 pool of platelets for every 5 units of red cells]), fresh frozen plasma (in a 1:1 ratio) and cryoprecipitate; tranexamic acid, eptacog alfa and calcium have also been advocated. Use of more recently donated packed red cells rather than older units may be beneficial.

‘haemostatic resuscitation’: early use of blood products to prevent/treat acute coagulopathy, including platelets (in a 1:1 ratio with packed red cells [1 pool of platelets for every 5 units of red cells]), fresh frozen plasma (in a 1:1 ratio) and cryoprecipitate; tranexamic acid, eptacog alfa and calcium have also been advocated. Use of more recently donated packed red cells rather than older units may be beneficial.

Jansen JO, Thomas R, Loudon MA, Brooks A (2009). Br Med J; 338: b1778

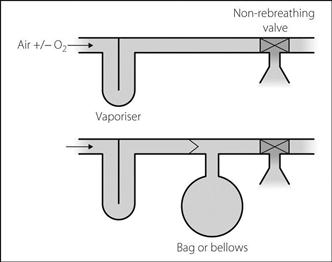

Damping. Progressive diminution of amplitude of oscillations in a resonant system, caused by dissipation of stored energy. Important in recording systems such as direct arterial BP measurement. In this context, damping mainly arises from viscous drag of fluid in the cannula and connecting tubing, compression of entrapped air bubbles, blood clots within the system and kinking. Excess damping causes a flattened trace which may be distorted (phase shift). The degree of damping is described by the damping factor (D); if a sudden change is imposed on a system, D = 1 if no overshoot of the trace occurs (critical damping; Fig. 49a). A marked overshoot followed by many oscillations occurs if D  1 (Fig. 49b), and an excessively delayed response occurs if D

1 (Fig. 49b), and an excessively delayed response occurs if D  1 (Fig. 49c). Optimal damping is 0.6–0.7 of critical damping, and produces the fastest response without excessive oscillations. D depends on the properties of the liquid within the system and the dimensions of the cannula and tubing.

1 (Fig. 49c). Optimal damping is 0.6–0.7 of critical damping, and produces the fastest response without excessive oscillations. D depends on the properties of the liquid within the system and the dimensions of the cannula and tubing.

Danaparoid sodium. Heparinoid mixture, containing no heparin, used for the prophylaxis of deep vein thrombosis. Useful as a heparin alternative in cases of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

Dandy–Walker syndrome, see Hydrocephalus

Dantrolene sodium. Hydantoin skeletal muscle relaxant that acts by binding to the ryanodine receptor and limits entry of calcium into myocytes. Used to treat spasticity, neuroleptic malignant syndrome and MH.

Krause T, Gerbershagen MU, Fiege M, et al (2004). Anaesthesia; 59: 364–73

Darrow’s solution. Hypotonic solution designed for iv fluid replacement in children suffering from gastroenteritis. Composed of sodium 122 mmol/l, chloride 104 mmol/l, lactate 53 mmol/l and potassium 35 mmol/l.

Data. In statistics, a series of observations or measurements.

– interval: does not include zero, e.g. Celsius temperature scale (the ‘zero’ is an arbitrary point in the scale; thus 10°C does not represent half as much heat as 20°C). The Kelvin scale is a ratio scale since 0 K does represent absence of heat and thus 10 K represents half as much heat as 20 K.

If they have a normal distribution, continuous data may be described by the mean and standard deviation as indicators of central tendency and scatter respectively (described as for ordinal data if not normally distributed).

– ordinal, e.g. ASA physical status. The difference between scores of 2 and 3 does not equal that between scores of 4 and 5, and a score of 4 is not ‘twice as unfit’ as a score of 2. Ordinal data are described by the median and percentiles (plus range).

– nominal, e.g. diagnosis, hair colour. May be dichotomous, e.g. male/female; alive/dead. Nominal data are described by the mode and a list of possible categories.

Different kinds of data require different statistical tests for correct analyses and comparisons: parametric tests for normally distributed data (most continuous data) and non-parametric tests for non-normally distributed data (categorical and some continuous data). The latter may often be ‘normalised’ by mathematical transformation, allowing application of the more sensitive parametric tests.

See also, Clinical trials; Statistical frequency distributions

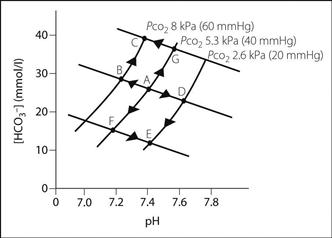

Davenport diagram. Graph of plasma bicarbonate concentration against pH, useful in interpreting and explaining disturbances of acid–base balance. Different lines may be drawn for different arterial PCO2 values, but for each line, bicarbonate falls as pH falls and increases as pH increases (Fig. 50).

• Can be used to demonstrate what happens in various acid–base disorders:

line BAD represents part of the titration curve for blood.

line BAD represents part of the titration curve for blood.

point A represents normal plasma.

point A represents normal plasma.

point B represents respiratory acidosis; i.e. a rise in arterial PCO2, reducing pH and increasing bicarbonate. In order to return pH towards normal, compensatory mechanisms (e.g. increased renal reabsorption) increase bicarbonate; i.e. move towards point C.

point B represents respiratory acidosis; i.e. a rise in arterial PCO2, reducing pH and increasing bicarbonate. In order to return pH towards normal, compensatory mechanisms (e.g. increased renal reabsorption) increase bicarbonate; i.e. move towards point C.

point D represents respiratory alkalosis; compensation (increased renal bicarbonate excretion) results in a move towards point E.

point D represents respiratory alkalosis; compensation (increased renal bicarbonate excretion) results in a move towards point E.

point G represents metabolic alkalosis; compensatory hypoventilation causes a move towards point C.

point G represents metabolic alkalosis; compensatory hypoventilation causes a move towards point C.

The same relationship may be displayed in different ways, e.g. the Siggaard-Andersen nomogram, which contains more information and is more useful clinically.

[Horace W Davenport (1912–2005), US physiologist]

Fig. 50 Davenport diagram (see text)

Davy, Sir Humphrey (1778–1829). Cornish-born scientist, inventor of the miner’s safety lamp. Discovered sodium, potassium, calcium and barium. Suggested the use of N2O (which he named ‘laughing gas’) for analgesia in 1799, whilst director of the Medical Pneumatic Institution in Bristol. Later became President of the Royal Society.

Riegels N, Richards MJBM (2011). Anesthesiology; 114: 1282–8

reduced psychological upheaval for patients, especially children.

reduced psychological upheaval for patients, especially children.

reduced requirement for nursing care and hospital services, and thus cheaper.

reduced requirement for nursing care and hospital services, and thus cheaper.

Standards of anaesthetic and surgical care and equipment (including preoperative preparation, monitoring and recovery facilities) are as for inpatient surgery.

• Patients may be managed within:

• Patient selection: traditional rigid criteria (e.g. relating to age, ASA physical status, BMI) are now generally considered unnecessary, three main criteria being:

medical condition: patient should be fit or any chronic disease should be stable/controlled.

medical condition: patient should be fit or any chronic disease should be stable/controlled.

premedication is usually omitted, although short-acting drugs (e.g. temazepam) are sometimes used.

premedication is usually omitted, although short-acting drugs (e.g. temazepam) are sometimes used.

general principles are as for any anaesthetic, but rapid recovery is particularly desirable. Thus short-acting drugs are usually used, e.g. propofol, fentanyl, alfentanil. Sevoflurane and desflurane are commonly selected volatile agents because of their low blood gas solubility and rapid recovery. Tracheal intubation is acceptable but is usually avoided if possible. Suxamethonium is often avoided as muscle pains are more common in ambulant patients.

general principles are as for any anaesthetic, but rapid recovery is particularly desirable. Thus short-acting drugs are usually used, e.g. propofol, fentanyl, alfentanil. Sevoflurane and desflurane are commonly selected volatile agents because of their low blood gas solubility and rapid recovery. Tracheal intubation is acceptable but is usually avoided if possible. Suxamethonium is often avoided as muscle pains are more common in ambulant patients.

• Postoperative assessment must be performed before discharge; the following are usually required:

full orientation and responsiveness.

full orientation and responsiveness.

ability to walk, dress, drink and pass urine.

ability to walk, dress, drink and pass urine.

D-dimer, see Fibrin degradation products

Dead space. Volume of inspired air that takes no part in gas exchange. Divided into:

anatomical dead space: mouth, nose, pharynx and large airways not lined with respiratory epithelium. Measured by Fowler’s method.

anatomical dead space: mouth, nose, pharynx and large airways not lined with respiratory epithelium. Measured by Fowler’s method.

alveolar dead space: ventilated lung normally contributing to gas exchange, but not doing so because of impaired perfusion. Thus represents one extreme of

alveolar dead space: ventilated lung normally contributing to gas exchange, but not doing so because of impaired perfusion. Thus represents one extreme of  mismatch.

mismatch.

Physiological dead space equals anatomical plus alveolar dead space. It is calculated using the Bohr equation. Assessment may be useful in monitoring  mismatch in patients with extensive respiratory disease, especially when combined with estimation of shunt fraction. Normally equals 2–3 ml/kg; i.e. 30% of normal tidal volume. In rapid shallow breathing, alveolar ventilation is reduced despite a normal minute ventilation, because a greater proportion of tidal volume is dead space.

mismatch in patients with extensive respiratory disease, especially when combined with estimation of shunt fraction. Normally equals 2–3 ml/kg; i.e. 30% of normal tidal volume. In rapid shallow breathing, alveolar ventilation is reduced despite a normal minute ventilation, because a greater proportion of tidal volume is dead space.

Apparatus dead space represents ‘wasted’ fresh gas within anaesthetic equipment. Minimal lengths of tubing should lie between the fresh gas inlet of a T-piece and the patient, especially in children, whose tidal volumes are small. Facemasks and their connections may considerably increase dead space.

– mortality/survival prediction and allocation of resources; triage.

– relief of symptoms, e.g. pain management, palliative care.

– CPR.

– diagnosis of brainstem death.

– informed consent before treatments (i.e. the risk of death).

– withdrawing treatment or resisting aggressive interventions when they are likely to be futile.

– do not attempt resuscitation orders.

– reporting of deaths to the coroner.

– claims of negligence or manslaughter.

– adequate preparation and support of patients, relatives and staff.

– counselling of staff after a patient’s death, especially when unexpected.

– organisational/educational: audit; surveys of ICU and anaesthetic morbidity and mortality; risk management.

Debrisoquine sulphate. Antihypertensive drug, acting by preventing noradrenaline release from postganglionic adrenergic neurones. Similar in effects to guanethidine, but does not deplete noradrenaline stores. No longer available in UK.

Decamethonium dibromide/diiodide. Depolarising neuromuscular blocking drug, introduced in 1948. Blockade lasts 15–20 min. No longer in use in the UK.

Decerebrate posture. Abnormal posture resulting from bilateral midbrain or pontine lesions (below the level of the red nucleus). Composed of internal rotation and hyperextension of all limbs, with hyperextension of neck and spine, and absent righting reflexes. Similar posturing may be seen in severe structural brain damage or coning.

Declamping syndrome, see Aortic aneurysm, abdominal

Decompression sickness (Caisson disease). Syndrome following rapid passage from a high atmospheric pressure environment to one of lower atmospheric pressure (e.g. surfacing after underwater diving), especially if followed by air transport at high altitude. Caused by formation of nitrogen bubbles as the gas comes out of solution, which it does readily because of its low solubility. Bubbles may embolise to or form in various tissues, giving rise to widespread symptoms in: the joints (‘the bends’); the CNS (‘the staggers’); the skin (‘the creeps’); the lungs (‘the chokes’). Treated by immediate recompression followed by slow, controlled depressurisation.

[Caisson: pressurised watertight chamber used for construction work in deep water]

Vann RD, Butler FK, Mitchell SJ. Moon RE (2011). Lancet; 377: 153–64

Decontamination of anaesthetic equipment, see Contamination of anaesthetic equipment

Decubitus ulcers (Pressure sores). May result from a number of factors:

malnutrition, including mineral deficiency.

malnutrition, including mineral deficiency.

predisposing conditions, e.g. diabetes mellitus, immunodeficiency.

predisposing conditions, e.g. diabetes mellitus, immunodeficiency.

diarrhoea or urinary incontinence.

diarrhoea or urinary incontinence.

[Judy Waterlow, British nurse]

Keller BP, Wille J, van Ramshorst B, van der Werken C (2002). Intensive Care Med; 28: 1379–88

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Thrombus formation in the deep veins, usually of the leg and pelvis. A common postoperative complication, especially following major joint replacement, colorectal surgery and surgery for cancer. The true incidence is unknown but may exceed 50% in high-risk patients. Carries high risk of PE. May rarely cause systemic embolisation via a patent foramen ovale (present in 30% of the population at autopsy).

• Triad of predisposing factors described by Virchow in 1856:

venous stasis, e.g. low cardiac output (e.g. cardiac failure, MI, dehydration), pelvic venous obstruction, prolonged immobility.

venous stasis, e.g. low cardiac output (e.g. cardiac failure, MI, dehydration), pelvic venous obstruction, prolonged immobility.

vessel wall damage, e.g. direct trauma, inflammation, varicosities, infiltration.

vessel wall damage, e.g. direct trauma, inflammation, varicosities, infiltration.

increased blood coagulability, e.g. trauma, malignancy, pregnancy, oestrogen or antifibrinolytic administration, hereditary hypercoagulability, smoking (see Coagulation disorders).

increased blood coagulability, e.g. trauma, malignancy, pregnancy, oestrogen or antifibrinolytic administration, hereditary hypercoagulability, smoking (see Coagulation disorders).

More common in old age, sepsis and obesity. Increased risk after surgery is thought to be related to increased platelet adhesiveness and activation of the coagulation cascade caused by tissue trauma, exacerbated by possible venous damage and immobility.

Clinical diagnosis is unreliable but suggested by tenderness, swelling and increased temperature of the calf, and pain on passive dorsiflexion of the foot (Homans’ sign). The upper leg may also be involved. Accompanying superficial thrombophlebitis may be absent. Investigations include: Doppler ultrasound; impedance plethysmography; thermography; uptake of radiolabelled fibrinogen or platelets; and venography (the ‘gold standard’ test). Measurement of FDPs (e.g. D-dimer) is also used, a normal level excluding DVT.

Treated by systemic anticoagulation with unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin; the latter are more commonly used since they can be given sc once a day in fixed doses based on the patient’s weight, without needing laboratory monitoring. This tends to offset the increased drug cost. In addition, haemorrhagic complications are less frequent than with unfractionated heparin. Low-molecular-weight heparins are thus used to treat DVT without admission to hospital in selected patients. Warfarin is administered orally, and heparin discontinued when a prothrombin time of 2–3 times normal is achieved. Long-term interruption of leg blood flow may not be prevented, and prevention of PE has never been proven. Initial bed rest, leg elevation and analgesia are also prescribed, although there is no evidence that these measures affect outcome. Optimal duration of warfarin therapy is controversial but the usual duration ranges from 6 weeks to 6 months, depending on underlying risk factors. Surgical removal of thrombus has been performed, but reaccumulation usually occurs, possibly due to vessel wall damage. Use of fibrinolytic drugs is controversial.

– intermittent pneumatic compression of the calves peri- and postoperatively.

– graduated compression stockings.

– encouragement of postoperative leg exercises and early mobilisation.

reduction of intravascular coagulation:

reduction of intravascular coagulation:

– fibrinolytic drugs: not shown to prevent DVT.

– antiplatelet drugs: have been shown to prevent DVT and PE.

– heparin and warfarin anticoagulation: effective but with risk of haemorrhage. Low-dose heparin is widely used (5000 units sc 2 h preoperatively then bd/tds) and has been shown to be effective in reducing DVT and fatal PE. Low-molecular-weight heparin reduces DVT with reduced haemorrhagic side effects (for doses, see Heparin). Dihydroergotamine has been used together with heparin, and is thought to reduce the incidence further, possibly via venous vasoconstriction.

– discontinuation of oral contraceptives preoperatively.

– epidural/spinal anaesthesia is thought to be associated with increased fibrinolysis and reduced risk of DVT.

– statins reduce the incidence of DVT.

Low-molecular-weight heparin and compression stockings are most commonly used.

[Rudolph LW Virchow (1821–1902), German pathologist; John Homans (1877–1954), US surgeon]

Defibrillation. Application of an electric current across the heart, to convert (ventricular) fibrillation to sinus rhythm. Use of electricity was described in the late 1700s/early 1800s (e.g. by Kite), but modern use arose from experiments in the 1930s–1950s, largely by Kouwenhoven. The first successful resuscitation of a patient from VF was by Claude Beck in 1947. Direct current is more effective and less damaging than alternating current.

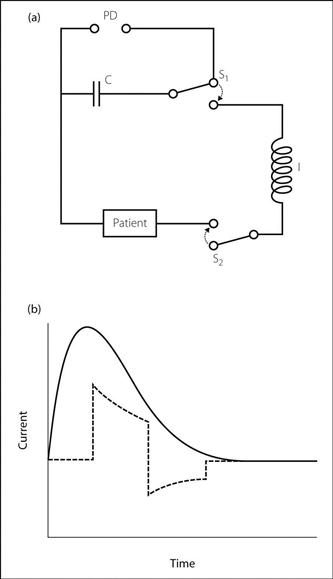

Modern defibrillators contain a capacitor, with potential difference between its plates of 5000–8000 V (Fig. 51a). Stored charge is released during discharge; the energy released is proportional to the potential difference. An inductor controls the shape and duration of the delivered electrical pulse. With traditional monophasic defibrillation up to 400 J is used for external defibrillation (360 J actually delivered to the patient because of energy losses), and 20–50 J for internal defibrillation. The current pulse (up to 30 A) causes synchronous contraction of the heart muscle followed by a refractory period, thus allowing sinus rhythm to occur. Modern devices deliver lower-energy biphasic waveforms, which are more effective at terminating VF; current is delivered in one direction followed immediately by a second current in the opposite direction (Fig. 51b). More sophisticated developments include the ability to measure and correct for the transthoracic impedance by varying the shock delivered.

Firm application of paddles (one to the right of the sternum, the other over the apex of the heart – taking care to avoid any implanted devices) using conductive jelly increases efficiency, although self-adhesive pads are now preferred. They may also be placed on the front and back of the chest. Thoracic impedance is reduced by the first shock, so a second discharge at the same setting will deliver greater energy to the heart. For children, 4 J/kg is used. Lower energy levels and R-wave synchronisation are used in cardioversion. Repeated shocks may result in myocardial damage.

Hazards include electrocution of members of the resuscitation team and fire. Standing clear of the patient and disconnection of the patient’s oxygen supply (moving it 1 m from his/her chest) during defibrillation is mandatory.

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) are used for recurrent VF/VT or predisposing conditions (see Defibrillators, implantable cardioverter).

[William Kouwenhoven (1886–1975), US engineer; Claude S Beck (1894–1971) US thoracic surgeon]

See also, individual arrhythmias; Cardiac pacing; Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

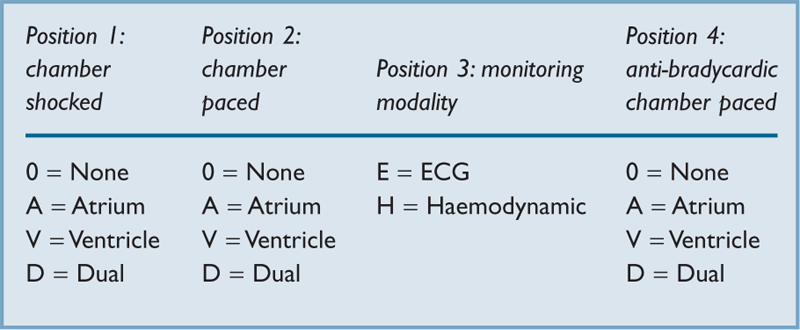

Defibrillators, implantable cardioverter (ICD). Specialised pacemakers designed to detect and treat potentially life-threatening arrhythmias. Have similar principles to pacemakers but are described by a different coding system (Table 18). Depending on the patient’s arrhythmia, they may respond with anti-tachycardia pacing, anti-bradycardia pacing, a low-energy synchronised shock (< 5 J) or a high-energy unsynchronised shock. A particular concern during surgery is the potential for electromagnetic interference (e.g. from surgical diathermy) to be misinterpreted as VF or VT, causing inappropriate discharge of the defibrillator. Defibrillator function may be disabled either by preoperative reprogramming of the ICD or intraoperative application of a magnet. The latter may have unpredictable effects on the ICD and this should be confirmed with the ICD manufacturer before use.

Anaesthetic management for insertion is similar to that for pacemakers.

Deflation reflex. Stimulation of inspiration by lung deflation, initiated by pulmonary stretch receptors. Of uncertain significance in humans.

Degrees of freedom. In statistics, the number of observations in a sample that can vary independently of other observations. For n observations, each observation may be compared with n – 1 others; i.e. degrees of freedom = n – 1. For chi-squared analysis, it equals the product of (number of rows – 1) and (number of columns – 1).

Dehydration. Reflects loss of water from ECF, alone or with intracellular fluid (ICF) depletion. Sodium is usually lost concurrently, giving rise to hypernatraemia or hyponatraemia, depending on the relative degrees of loss. If ECF osmolality rises, water passes from ICF into ECF by osmosis. A predominant water loss is shared by both ICF and ECF; water and sodium loss is borne mainly by ECF if osmolality is not greatly affected. Thus fever, lack of intake, diabetes insipidus and osmotic diuresis (mainly water loss) may be tolerated for longer periods than severe vomiting, diarrhoea, intestinal obstruction and diuretic therapy (water and sodium loss), although reduced water intake often accompanies the latter conditions.

The physiological response to dehydration includes increased thirst, vasopressin secretion and renin/angiotensin system activation, and CVS compensation for hypovolaemia via osmoreceptor and baroreceptor mechanisms.

• Clinical features are related to the extent of water loss:

5% of body weight: thirst, dry mouth.

5% of body weight: thirst, dry mouth.

5–10% of body weight: decreased intraocular pressure, peripheral perfusion and skin turgor, oliguria, orthostatic hypotension. JVP/CVP are reduced.

5–10% of body weight: decreased intraocular pressure, peripheral perfusion and skin turgor, oliguria, orthostatic hypotension. JVP/CVP are reduced.

Blood urea and haematocrit are increased, and urine has high osmolality (over 300 mosmol/kg) and low sodium content (under 10 mmol/l), assuming normal renal function.

Treatment includes oral and iv fluid administration; in the latter, dextrose solutions are favoured for combinations of ICF and ECF losses and electrolyte solutions for ECF losses alone. Dehydration should be corrected preoperatively.

Delirium tremens (DTs). Alcohol withdrawal syndrome seen in chronic heavy drinkers. Occurs in about 5% of cases. Thought to be caused by reduction in both inhibitory GABAA activity and presynaptic sympathetic inhibition; hypomagnesaemia and hypocalcaemia may contribute to CNS hyperexcitability. Characterised by:

Treatment includes: rehydration; correction of hypoglycaemia and electrolyte imbalance; and sedation. Benzodiazepines are the agents of choice, although carbamazepine and phenobarbital have also been used. Prevention is important and is achieved with the same drugs.

Demand valves. Valves that allow self-administration of inhalational anaesthetic agents; they may form part of intermittent-flow anaesthetic machines, or be used to administer Entonox. The standard Entonox valve was developed from underwater breathing apparatus, and contains a two-stage pressure regulator within one unit that fits directly to the cylinder. The first-stage regulator is similar to those on anaesthetic machines. At the second stage, gas flow is prevented by a rod which seals the valve. The patient’s inspiratory effort moves a sensing diaphragm and tilts the rod, opening the valve. Very small negative pressures are required to produce gas flow of up to 300 l/min. The mouthpiece/mask elbow piece incorporates an expiratory valve and a safety (overpressure) valve. Other demand valves for use with Entonox have the second-stage (demand) regulator attached to the patient’s mask.

Demeclocycline hydrochloride. Tetracycline, used as an antibacterial drug and to treat the syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion (SIADH), possibly by blocking the renal action of vasopressin.

Demyelinating diseases. Non-specific group of disorders, with abnormality of the axonal myelin sheath as the predominant feature. Defective myelin may be present at birth (dysmyelinating) or may arise in areas of previously normal myelin (demyelinating). Multiple (disseminated) sclerosis (MS) is the commonest of the latter and is considered below; others include post-immunisation or parainfectious encephalomyelitis.

Diagnosed clinically, supported by gadolinium-enhanced MRI findings and the presence of oligoclonal IgG bands in the CSF. Evoked potential testing may support the diagnosis.

Treatment is supportive, but may include corticosteroids. Interferon beta has been shown to decrease the relapse rate in relapsing remitting MS. Hyperbaric O2 therapy has been advocated but results are disappointing.

Anaesthetic implications are unclear, since effects of stress, surgery and anaesthesia cannot be separated from the spontaneity of new lesion formation. Thus case reports are often conflicting in their conclusions. Increases in body temperature should be avoided; avoidance of anticholinergic drugs has been suggested. An abnormal response to neuromuscular blocking drugs, including hyperkalaemia following suxamethonium, has been suggested but without direct evidence. Prolonged muscle spasms may occur, but epilepsy is rare. Increased tendency to DVT has been suggested. Impairment of respiratory and autonomic control has been reported. Although not contraindicated, epidural or spinal anaesthesia has sometimes been avoided for medicolegal reasons, although it is increasingly used as the preferred method of obstetric analgesia and anaesthesia.

Denervation hypersensitivity. Increased sensitivity of denervated skeletal muscle to acetylcholine. Develops approximately 4–5 days after denervation, and is due to proliferation of extrajunctional acetylcholine receptors over the entire muscle membrane, instead of being restricted to the neuromuscular junction. Thought to be the mechanism underlying the exaggerated hyperkalaemic response to suxamethonium seen after peripheral nerve injuries. Its cause is unclear. Also occurs in smooth muscle.

Density. For a substance, defined as its mass per unit volume. Relative density (specific gravity) is the mass of any volume of substance divided by the mass of the same volume of water.

Dental nerve blocks, see Mandibular nerve blocks; Maxillary nerve blocks

Dental surgery. Anaesthesia may be required for tooth extraction, conservative dental surgery or maxillofacial surgery.

• For outpatient ambulatory surgery, the following may be used:

mandibular and maxillary nerve blocks.

mandibular and maxillary nerve blocks.

iv sedation, e.g. Jorgensen technique and variants.

iv sedation, e.g. Jorgensen technique and variants.

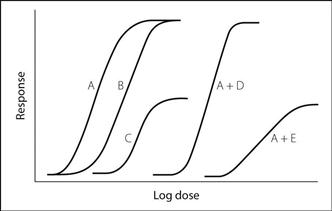

inhalational anaesthetic agents, including N2O and/or volatile agents. Traditionally administered from intermittent-flow anaesthetic machines, using nasal inhalers, although continuous-flow machines are increasingly used. Quantiflex apparatus is also used. Occupational exposure to N2O is a hazard, especially in small dental surgeries.

inhalational anaesthetic agents, including N2O and/or volatile agents. Traditionally administered from intermittent-flow anaesthetic machines, using nasal inhalers, although continuous-flow machines are increasingly used. Quantiflex apparatus is also used. Occupational exposure to N2O is a hazard, especially in small dental surgeries.

• General anaesthetic principles are as for day-case surgery; main problems:

high proportion of children, usually anxious and unpremedicated.

high proportion of children, usually anxious and unpremedicated.

shared airway as for ENT surgery. Airway obstruction, mouth breathing during nasally administered anaesthesia, airway soiling and breath-holding may occur. For these reasons the traditional nasal inhaler (mask-like device held over the nose from behind the patient’s head) is now rarely used by hospital anaesthetists.

shared airway as for ENT surgery. Airway obstruction, mouth breathing during nasally administered anaesthesia, airway soiling and breath-holding may occur. For these reasons the traditional nasal inhaler (mask-like device held over the nose from behind the patient’s head) is now rarely used by hospital anaesthetists.

arrhythmias may arise from use of adrenaline solutions, stimulation of the trigeminal nerve, anxiety and hypercapnia.

arrhythmias may arise from use of adrenaline solutions, stimulation of the trigeminal nerve, anxiety and hypercapnia.

Mouth packs may be employed to prevent airway soiling. They should be placed under the tongue, pushing the tongue back to seal the mouth from the airway. Mouth gags or props are often used to hold the mouth open.

Dental surgery is performed on an inpatient surgery basis if airway obstruction, cardiac or respiratory disease, coagulation disorders or extreme obesity is present. Nasotracheal intubation is usually performed, and a throat pack placed. Use of concentrated adrenaline solutions by dentists is still common, e.g. 1:80 000, despite anaesthetists’ objections.

Depolarising neuromuscular blockade (Phase I block). Follows depolarisation of the postsynaptic membrane of the neuromuscular junction via activation of acetylcholine receptors, but with only slow repolarisation. Effect of depolarisation of presynaptic receptors is unclear, but may be partially responsible for the fasciculation seen. Suxamethonium is the most commonly used and widely available drug; previously used drugs include decamethonium and suxethonium.

• Features of depolarising blockade:

may be preceded by fasciculation.

may be preceded by fasciculation.

does not exhibit fade or post-tetanic potentiation.

does not exhibit fade or post-tetanic potentiation.

increased by acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.

increased by acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.

potentiated by respiratory alkalosis, hypothermia, hyperkalaemia and hypermagnesaemia.

potentiated by respiratory alkalosis, hypothermia, hyperkalaemia and hypermagnesaemia.

antagonised by non-depolarising neuromuscular blocking drugs.

antagonised by non-depolarising neuromuscular blocking drugs.

development of dual block with excessive dosage of drug.

development of dual block with excessive dosage of drug.

See also, Neuromuscular blockade monitoring; Non-depolarising neuromuscular blockade

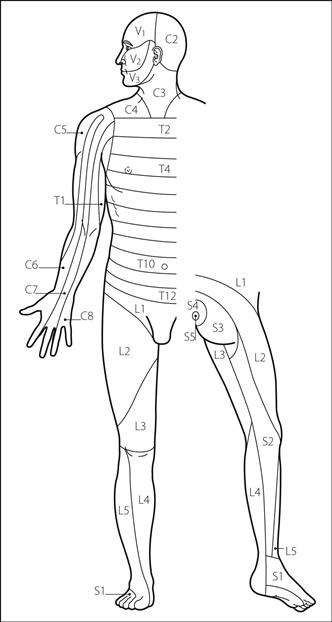

Dermatomes. Lateral walls of somites (segmental units appearing longitudinally early in embryonic development), which form the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Cutaneous sensation retains the somatic distribution, corresponding to segmental spinal levels. Thus areas of skin are supplied by particular spinal nerves; useful in determining the extent of regional anaesthetic blocks and localising neurological lesions (Fig. 52).

Fig. 52 Dermatomal nerve supply

Dermatomyositis, see Polymyositis

Desensitisation block, see Dual block

Desferrioxamine mesylate. Chelating agent used in the treatment of aluminium and iron poisoning.

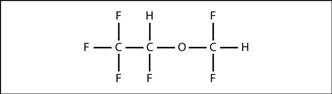

Desflurane. 1-Fluoro-2,2,2-trifluoroethyl difluoromethyl ether. Inhalational anaesthetic agent, synthesised in the 1960s but only introduced in the UK in 1994. Chemical structure is the same as isoflurane, but with the chlorine atom replaced by fluorine (Fig. 53).

colourless liquid with slightly pungent vapour.

colourless liquid with slightly pungent vapour.

SVP at 20°C 88 kPa (673 mmHg).

SVP at 20°C 88 kPa (673 mmHg).

MAC 5–7% in adults; 7.2–10.7% in children.

MAC 5–7% in adults; 7.2–10.7% in children.

supplied in liquid form with no additive.

supplied in liquid form with no additive.

may react with dry soda lime to produce carbon monoxide (see Circle systems).

may react with dry soda lime to produce carbon monoxide (see Circle systems).

requires the use of an electrically powered vaporiser due to its low boiling point.

requires the use of an electrically powered vaporiser due to its low boiling point.

• Effects:

– rapid induction (although limited by its irritant properties) and recovery.

– EEG changes as for isoflurane.

– may increase cerebral blood flow, although the response of cerebral vessels to CO2 is preserved.

– ICP may increase due to imbalance between the production and absorption of CSF.

– reduces CMRO2 as for isoflurane.

– has poor analgesic properties.

– respiratory depressant, with increased rate and decreased tidal volume.

– myocardial ischaemia may occur if sympathetic stimulation is excessive.

– arrhythmias uncommon, as for isoflurane. Little myocardial sensitisation to catecholamines.

– renal and hepatic blood flow generally preserved.

– dose-dependent uterine relaxation (although less than isoflurane and sevoflurane).

– skeletal muscle relaxation; non-depolarising neuromuscular blockade may be potentiated.

2–6% is usually adequate for maintenance of anaesthesia, with higher concentrations for induction. Uptake and excretion are rapid because of its low blood gas solubility; thus it has been suggested as the agent of choice in day-case surgery, although this is controversial. Although more expensive than isoflurane, less drug is required to maintain anaesthesia once equilibrium is reached, and equilibrium is reached much more quickly; it may therefore be more economical for use during longer procedures.

Fig. 53 Structure of desflurane

Desmopressin (1-desamino-8-D-argininevasopressin; DDAVP). Analogue of vasopressin, with a longer-lasting antidiuretic effect but minimal vasoconstrictor actions. Used to diagnose and treat non-nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. May also be used to increase factor VIII and von Willebrand factor levels by 2–4 times in mild haemophilia or von Willebrand’s disease. Has also been used to improve platelet function in renal failure and to reduce blood loss in cardiac surgery.

• Dosage:

diabetes insipidus: 10–20 µg od/bd, intranasally; 100–200 µg orally tds; or 1–4 µg/day iv/sc/im.

diabetes insipidus: 10–20 µg od/bd, intranasally; 100–200 µg orally tds; or 1–4 µg/day iv/sc/im.

• Side effects: fluid retention, hyponatraemia, pallor, abdominal cramps, and angina in susceptible patients.

Dew point. Temperature at which ambient air is saturated with water vapour. As air containing water vapour cools (e.g. when it is in contact with a cold surface) condensation occurs when the dew point is reached (e.g. misting on the surface of spectacles on entering a warm room from the cold). This process may be used to measure humidity.

Dexamethasone. Corticosteroid with high glucocorticoid but minimal mineralocorticoid activity and long duration of action, thus used where sustained activity is required but when water retention would be harmful, e.g. cerebral oedema. Also used in congenital adrenal hyperplasia, to reduce oedema following ENT surgery, and in the diagnosis of Cushing’s disease. Other uses include prevention and treatment of PONV, and stimulation of fetal lung maturation in premature labour.

Dexmedetomidine hydrochloride. Selective α-adrenergic receptor agonist, with about 1300–1600 times the affinity for α2-receptors as for α1. Rapidly distributed after iv injection (half-life about 6 min) with an elimination half-life of 2–2.5 h. Volume of distribution is about 1.3 l/kg. 94% protein-bound. Inactivated mainly to glucuronides with 80–90% excreted in the urine. Has similar effects to clonidine but more predictable and easier to titrate, e.g. for sedation in ICU.

Dextrans. Group of branched polysaccharides of 200 000 glucose units, derived from the action of bacteria (Leuconostoc mesenteroides) on sucrose. Partial hydrolysis produces molecules of average mw 40 kDa, 70 kDa and 110 kDa (dextrans 40, 70 and 110 respectively). Dextran 40 is used to promote peripheral blood flow, e.g. in arterial insufficiency and in prophylaxis of DVT. Dextrans 70 and 110 are used mainly for plasma expansion; the latter is now rarely used and is unavailable in the UK. Dextrans increase peripheral blood flow by reducing viscosity, and may coat both endothelium and cellular elements of blood, reducing their interaction. They reduce platelet adhesiveness, possibly impair factor VIII activity and may have anti-inflammatory properties.

Size of dextran molecules is directly proportional to the degree of plasma expansion produced and the molecules’ circulation time. Half-life ranges from 15 min for small molecules to several days for larger ones. Major route of excretion is via the kidneys.

renal failure caused by tubular obstruction by dextran casts; mainly occurs with dextran 40 when used in hypovolaemia; concurrent water and electrolyte administration should be provided.

renal failure caused by tubular obstruction by dextran casts; mainly occurs with dextran 40 when used in hypovolaemia; concurrent water and electrolyte administration should be provided.

anaphylaxis: thought to result from previous cross-immunisation against bacterial antigens. Its incidence is reduced from 1:4500 to 1:84 000 by pretreatment with 3 g dextran 1 (mw 1000), to occupy and block antigen binding sites of circulating antibodies to dextran.

anaphylaxis: thought to result from previous cross-immunisation against bacterial antigens. Its incidence is reduced from 1:4500 to 1:84 000 by pretreatment with 3 g dextran 1 (mw 1000), to occupy and block antigen binding sites of circulating antibodies to dextran.

Dextromoramide tartrate. Opioid analgesic drug, related to methadone. Introduced in 1956. Less sedating, and shorter acting (duration 2–3 h) than morphine, but with similar effects. No longer available in the UK.

Dextropropoxyphene hydrochloride/napsilate. Opioid analgesic drug, related to methadone. Prepared in 1953. Poorly effective alone, but effective when combined with paracetamol (as co-proxamol). Overdose of this combination is particularly dangerous; initial respiratory depression and coma (due to dextropropoxyphene) may be treated correctly but later liver failure (due to paracetamol poisoning) may occur if appropriate prophylaxis is not given. Safety concerns, even at or just above normal doses, led to co-proxamol’s phased withdrawal from the UK in 2005.

Dextrose solutions. IV fluids available as 5, 10, 20, 25 and 50% solutions in water (50, 100, 200, 250 and 500 g/l respectively). Once administered, the glucose is rapidly metabolised and the water distributed to all body fluid compartments. Thus used in hypoglycaemia, and to replace water losses. Also used with insulin to treat acute hyperkalaemia.

Excess administration may result in hyponatraemia. Solutions of higher concentrations are increasingly hypertonic, acidic and viscous; they may cause thrombophlebitis if infused peripherally. Osmolality of 5% dextrose solution is 278 mosmol/kg; of 10% solution 523 mosmol/kg. pH of 5% solution is approximately 4.0. May cause haemolysis of stored erythrocytes when infused iv immediately before stored blood without first flushing the line with saline, presumably because the dextrose is taken up and metabolised by the cells to leave a hypo-osmotic solution.

Dezocine. Synthetic opioid analgesic drug, related to pentazocine; available in the USA but not in the UK. Comparable in potency, onset and duration of action to morphine. Has some opioid receptor antagonist activity, less than that of nalorphine but greater than that of pentazocine. Administered im or iv in doses of 2.5–20 mg.

Diabetes insipidus. Polyuria and polydipsia associated with reduced vasopressin activity, either because secretion by the pituitary gland is reduced (cranial/neurogenic) or the kidneys are unresponsive (nephrogenic):

cranial: occurs in head injury, neurosurgery (especially post-pituitary surgery), intracranial tumours. Rarely familial.

cranial: occurs in head injury, neurosurgery (especially post-pituitary surgery), intracranial tumours. Rarely familial.

nephrogenic: caused by drugs, e.g. lithium, demeclocycline and gentamicin; a rare X-linked recessive form may also occur.

nephrogenic: caused by drugs, e.g. lithium, demeclocycline and gentamicin; a rare X-linked recessive form may also occur.

Characterised by inappropriate production of large volumes of dilute urine, with raised plasma osmolality. Patients cannot concentrate their urine in response to water deprivation. The two types are distinguished by their response to administered vasopressin.

cranial: desmopressin (synthetic vasopressin analogue) 10–20 µg od/bd intranasally; 100–200 µg orally tds; or 1–4 µg/day iv/sc/im.

cranial: desmopressin (synthetic vasopressin analogue) 10–20 µg od/bd intranasally; 100–200 µg orally tds; or 1–4 µg/day iv/sc/im.

Anaesthetic considerations are related to impaired fluid balance with hypovolaemia, dehydration, hypernatraemia and other electrolyte imbalance. Careful attention to fluid balance, with monitoring of urine and plasma osmolality and electrolytes, is required.

Diabetes mellitus. Disorder of glucose metabolism characterised by relative or total lack of insulin or insulin resistance. This results in lipolysis, gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis, with hepatic conversion of fatty acids to ketone bodies, and hyperglycaemia. The resultant glycosuria causes an osmotic diuresis, with polyuria, polydipsia and excessive sodium and potassium loss.

• May be:

– pancreatic disease, e.g. pancreatitis, malignancy.

– insulin antagonism, e.g. corticosteroids, Cushing’s syndrome, acromegaly, phaeochromocytoma.

Classically divided into type 1 (insulin-dependent; IDDM), presenting in children or young adults, and type 2 (non-insulin-dependent; NIDDM), presenting in adults (and occasionally children) who are usually obese. Type 1 DM is an autoimmune disease, with 85% of patients having antibodies against pancreatic islet cells, and results in low or absent circulating insulin; treatment is with exogenous insulin. Type 2 DM is due to a relative lack of insulin and insulin resistance and is caused by excessive calorie intake and obesity in genetically susceptible individuals; it is treated with diet control, oral hypoglycaemic drugs (sulphonylureas, biguanides, acarbose, thiazolidinediones and meglitinides), a combination of oral hypoglycaemic drugs and insulin, or insulin alone.

The World Health Organization suggests the following diagnostic criteria:

symptoms + plasma glucose concentration > 11.1 mmol/l,

symptoms + plasma glucose concentration > 11.1 mmol/l,

or two fasting glucose concentrations > 7.0 mmol/l,

or two fasting glucose concentrations > 7.0 mmol/l,

or glucose concentration > 11.1 mmol/l, 2 h after ingestion of glucose in a glucose tolerance test.

or glucose concentration > 11.1 mmol/l, 2 h after ingestion of glucose in a glucose tolerance test.

A random HbA1c measurement lacks sensitivity as a diagnostic marker.

arteriosclerosis causing ischaemic heart disease, peripheral vascular insufficiency and CVA. Microvascular involvement may cause cardiac failure and impaired ventricular function. Hypertension is more common than in non-diabetic subjects.

arteriosclerosis causing ischaemic heart disease, peripheral vascular insufficiency and CVA. Microvascular involvement may cause cardiac failure and impaired ventricular function. Hypertension is more common than in non-diabetic subjects.

autonomic and peripheral neuropathy, the latter sensory or motor. Single nerves may also be affected, including cranial nerves.

autonomic and peripheral neuropathy, the latter sensory or motor. Single nerves may also be affected, including cranial nerves.

retinopathy and cataract formation.

retinopathy and cataract formation.

skin: collagen thickening, blisters, necrobiosis lipoidica.

skin: collagen thickening, blisters, necrobiosis lipoidica.

increased susceptibility to infection and delayed wound healing.

increased susceptibility to infection and delayed wound healing.

Patients should be assessed for fitness and diabetic control, and scheduled for surgery at the beginning of the operating list. The aim is to avoid hyperglycaemia, ketoacidosis, hypoglycaemia and electrolyte imbalance:

– Alberti regimen: 1000 ml 10% dextrose + 10 units soluble insulin + 10 mmol potassium infused at 100 ml/h. The infusion is changed to contain more or less insulin according to regular testing with glucose reagent sticks. The preoperative insulin regimen is restarted when the patient is drinking and eating normally.

Regional techniques are often preferred because they interfere less with oral intake. Insulin requirements may be increased after major surgery as part of the stress response to surgery.

Pregnancy may precipitate or worsen diabetes, and close medical supervision is required. During labour, regimens usually involve iv infusions of 5% dextrose (e.g. 500 ml/8 h) with iv insulin rate adjusted accordingly. Epidural anaesthesia is usually suggested, since it reduces acidosis in labour and facilitates caesarean section if indicated.

Diabetic coma. Coma in diabetes mellitus may be caused by:

hypoglycaemia: caused by overdose of hypoglycaemic agent, excessive exertion or decreased food intake. Treatment includes iv glucose; iv/im glucagon may occasionally be useful in out-of-hospital situations.

hypoglycaemia: caused by overdose of hypoglycaemic agent, excessive exertion or decreased food intake. Treatment includes iv glucose; iv/im glucagon may occasionally be useful in out-of-hospital situations.

ketoacidosis: more common in insulin-dependent diabetics. Mortality is 6–10%, highest in old age. Often precipitated by other illness (e.g. infection and MI), since insulin requirements are increased. May develop insidiously.

ketoacidosis: more common in insulin-dependent diabetics. Mortality is 6–10%, highest in old age. Often precipitated by other illness (e.g. infection and MI), since insulin requirements are increased. May develop insidiously.

– of dehydration, e.g. hypotension, tachycardia.

– of acidosis, e.g. hyperventilation (Kussmaul breathing).

– smell of acetone on the breath.

– general management: O2 and airway control if required, nasogastric tube (gastric dilatation is common), urinary catheter, CVP measurement, ECG and other standard monitoring. Antibiotics are administered if infection is suspected. Prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin is routinely given.

– potassium supplementation is required despite any initial hyperkalaemia, since the body potassium deficit will be revealed once tissue uptake is stimulated by insulin. Suitable starting regimen: 10–20 mmol in the first litre of fluid; 10–40 mmol thereafter, depending on the plasma potassium after 1 h (repeated every few hours).

– bicarbonate therapy (guided by base excess) if pH is under 7.0–7.1.

– hypophosphataemia may require replacement, e.g. with potassium phosphate, 5–20 mmol/h.

hyperosmolar non-ketotic coma: typically seen in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and presents with slow onset with polyuria and progressive dehydration. Focal neurological features may occur. Blood glucose levels and osmolality are very high, with little or no ketonuria. Treatment includes small doses of insulin and 0.45% saline administered slowly iv. Cerebral oedema and convulsions may occur if rehydration is too rapid.

hyperosmolar non-ketotic coma: typically seen in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and presents with slow onset with polyuria and progressive dehydration. Focal neurological features may occur. Blood glucose levels and osmolality are very high, with little or no ketonuria. Treatment includes small doses of insulin and 0.45% saline administered slowly iv. Cerebral oedema and convulsions may occur if rehydration is too rapid.

lactic acidosis: usually occurs in elderly patients taking biguanides. Blood glucose may be normal, with little or no ketonuria.

lactic acidosis: usually occurs in elderly patients taking biguanides. Blood glucose may be normal, with little or no ketonuria.

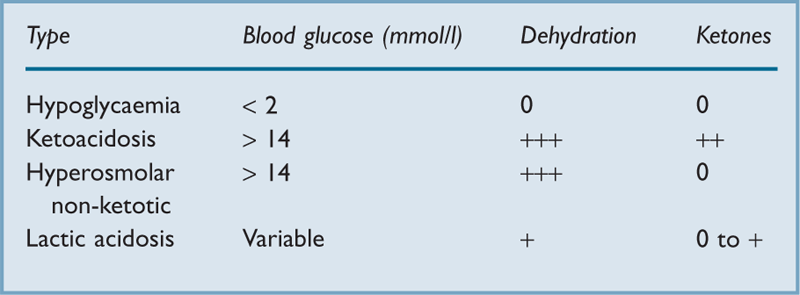

Clinical distinction between different types of diabetic coma is unreliable. Features aiding the diagnosis are shown in Table 19.

Diagnostic peritoneal lavage, see Peritoneal lavage

Dialysis. Artificial removal of water and solutes from the blood by selective diffusion across a semipermeable membrane. Indications include renal failure and severe cardiac failure unresponsive to diuretic therapy; may also remove drugs from the circulation in poisoning and overdoses, although only effective for smaller, non-protein-bound, water-soluble molecules. Collectively termed renal replacement therapy; many variants exist but they may be classified into:

All techniques rely on the diffusion of water and solutes across a semipermeable membrane; this passage may be manipulated by altering the hydrostatic or osmotic gradients across the membrane to optimise removal. In haemoperfusion, unwanted molecules (including lipid-soluble protein-bound ones) are adsorbed on to activated charcoal or an ion exchange resin, thus involving a different principle from that of dialysis. Both dialysis and adsorption techniques have been used to remove circulating toxins in hepatic failure, such techniques usually being termed liver dialysis.

Diamorphine hydrochloride (Diacetylmorphine; Heroin). Opioid analgesic drug, introduced in 1898; said to cause less constipation, nausea and hypotension than morphine, but more likely to cause addiction. Also suppresses coughing to a greater extent. Inactive prodrug that is rapidly hydrolysed by plasma cholinesterase to 6-monoacetylmorphine (responsible for the rapid onset of action), which is then slowly metabolised to morphine in the liver. Unavailable in the USA, Australia and parts of Europe (e.g. Germany) because of its reputation as a drug of addiction, although there is no evidence that medical use increases its abuse.

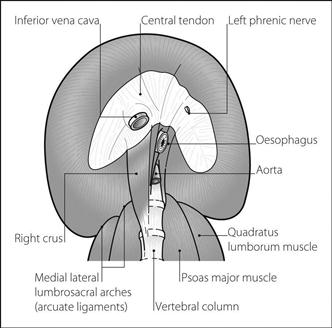

Diaphragm. Fibromuscular sheet separating the thorax from the abdomen. The main respiratory muscle, it flattens and descends vertically during inspiration, expanding the thoracic cavity. During expiration, it relaxes; in forced expiration, contraction of the anterior abdominal muscles pushes the diaphragm upwards.

central tendon, attached to the pericardium above.

central tendon, attached to the pericardium above.

peripheral muscular part. Attachments:

peripheral muscular part. Attachments:

– to the lower six ribs, costal cartilages and xiphisternum anteriorly.

Fig. 54 Inferior aspect of diaphragm

• Has three main openings transmitting the following structures:

inferior vena cava and right phrenic nerve at the level of T8.

inferior vena cava and right phrenic nerve at the level of T8.

oesophagus, vagus and gastric nerves and branches of the left gastric vessels at the level of T10.

oesophagus, vagus and gastric nerves and branches of the left gastric vessels at the level of T10.

aorta, thoracic duct and azygos vein at the level of T12.

aorta, thoracic duct and azygos vein at the level of T12.

The diaphragm is also pierced by the left phrenic nerve and splanchnic nerves.

The sympathetic chain passes behind the medial lumbosacral arch.

originally in the neck; descends during development, retaining its cervical nerve supply.

originally in the neck; descends during development, retaining its cervical nerve supply.

– oesophageal mesentery dorsally.

– right and left pleuroperitoneal membranes laterally.

– septum transversum anteriorly (forming the central tendon).

Diaphragmatic herniae. Herniation of abdominal viscera through the diaphragm into the thorax. Congenital herniae occur in approximately 1 in 4000 live births (1 in 2500 of all births), are often familial and are caused by failure of fusion of the various components of the diaphragm, e.g.:

Causes respiratory distress, cyanosis, scaphoid abdomen and bowel sounds audible in the thorax. Diagnosed clinically and by X-ray. The lung on the affected side is often hypoplastic, with decreased compliance and increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). Arterial hypoxaemia reflects immature lung tissue and impaired ventilation caused by presence of thoracic bowel, and persistent fetal circulation caused by the raised PVR. PVR is further increased by hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction.

Immediate management includes gastric decompression, improving oxygenation and decreasing PVR. PVR may be reduced by: avoiding hypocapnia and hypothermia; treating acidosis; use of inhaled nitric oxide and iv vasodilator drugs (e.g. sodium nitroprusside 1–2 µg/kg/min, prostacyclin 5–10 ng/kg/min).

IPPV by face-piece may increase gastric distension and should be avoided. IPPV is best performed via a tracheal tube, avoiding excessive inflation pressures since pneumothorax and acute lung injury may easily occur. Surgery is usually delayed until respiratory stability is achieved. High-frequency ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation have been used. Mortality is high if pneumothorax occurs and lung compliance is low.

Anaesthesia for surgical correction is as for paediatric anaesthesia. N2O is avoided because of distension of thoracic bowel. Excessive inflation of the hypoplastic lung at the end of the procedure should be avoided, since pneumothorax may occur. Abdominal closure may be difficult once the bowel is returned to the abdomen; postoperative IPPV may be required. The hypoplastic lung slowly re-expands, usually within a few days/weeks.

Acquired acute herniae may follow blunt or penetrating trauma or surgery. They may impair ventilation, or only cause symptoms if strangulation or obstruction occurs. Hiatus hernia is gradual in onset.

Bösenberg AT, Brown RA (2008). Curr Opin Anesthesiol; 21: 323–31

Diarrhoea. Common problem in the ICU which contributes to increased mortality; may result in dehydration and skin excoriation, and is upsetting to the patient and relatives. There are many causes, including:

infection (e.g. norovirus, Clostridium difficile, salmonella, campylobacter species).

infection (e.g. norovirus, Clostridium difficile, salmonella, campylobacter species).

Spurious (‘over-flow’) diarrhoea may occur in severe constipation. Non-infectious diarrhoea tends to occur without blood or mucus. Stools usually return to normal after the causal agent is removed.

Management includes appropriate investigation (stool cultures and microscopy, sigmoidoscopy; more invasive endoscopy or imaging may be required) and maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance. Probiotic agents may be useful. Specific causes are managed accordingly. Symptomatic treatment (e.g. with codeine or loperamide) may be indicated, although they are generally avoided in children and in infective diarrhoea.

Diastole, see Cardiac cycle; Diastolic interval

Diastolic blood pressure. Lowest arterial BP during diastole. Contributes to MAP and represents the pressure head for coronary blood flow.

Diastolic BP has been used to guide therapy in hypertension, treatment usually being advocated if it exceeds 90 mmHg, but this is controversial.

Diastolic interval. Duration of diastole. Shortened when heart rate is increased; e.g. equals about 0.62 s at 65 beats/min, but only 0.14 s at 200 beats/min.

Short diastolic intervals reduce coronary blood flow and ventricular filling.

Diastolic pressure time index (DPTI). Area between tracings of left ventricular pressure and aortic root pressure during diastole (see Fig. 61; Endocardial viability ratio). Represents the pressure head and time available for coronary blood flow; used to calculate endocardial viability ratio.

Diathermy (Bovie machine). Device used to coagulate blood vessels, and cut and destroy tissues during surgery, by the heating effect of an electric current passed through them. Alternating current with a frequency of 0.5–1 MHz is used; a sine wave pattern is employed for cutting and a damped or pulsed sine wave pattern for coagulation. Electrical stimulation of skeletal and cardiac muscle is negligible at these high frequencies. The current density is kept high at the site of intended damage by using small electrodes at this site, e.g. forceps tips.

– forceps or ‘pencil-point’, act as one electrode.

• Hazards:

interference with monitoring equipment.

interference with monitoring equipment.

may interfere with implantable cardioverter defibrillators and pacemaker function.

may interfere with implantable cardioverter defibrillators and pacemaker function.

[William T Bovie (1882–1958), US biophysicist]

See also, Cardiac pacing; Electrocution and electrical burns; Explosions and fires

Diazepam. Benzodiazepine, widely used for sedation, anxiolysis and as an anticonvulsant drug. Has been used for premedication, and to supplement or induce anaesthesia. Insoluble in water; original preparations caused pain on injection and thrombophlebitis. These are rare with emulsions of diazepam in soya bean oil.

Half-life is 20–70 h, with formation of active metabolites (that are renally excreted) including nordiazepam (half-life up to 120 h), desmethyldiazepam, oxazepam and temazepam. Thus repeated doses (e.g. in ICU) may lead to delayed recovery.

Diazoxide. Vasodilator drug, used for emergency treatment of severe hypertension. Acts directly on blood vessel walls by activating potassium channels. Previously indicated in hypertensive crisis, but the risk from sudden reduction in BP has resulted in its indication for iv use being restricted to severe hypertension associated with renal disease. Increases blood glucose level by increasing catecholamine levels and by reducing insulin release; may be used orally to treat chronic hypoglycaemia (e.g. in insulinoma).

• Dosage: 1–3 mg/kg (up to 150 mg) iv for hypertension, repeated after 5–15 min if required. MI and CVA have followed larger doses. For hypoglycaemia, 5 mg/kg/day orally.

• Side effects: tachycardia, hyperglycaemia, fluid retention.

Dibucaine number. Degree of inhibition of plasma cholinesterase by dibucaine (cinchocaine). Sample plasma is added to a benzoylcholine solution, and breakdown of the latter is observed using measurement of light absorption. This is repeated using plasma pretreated with a 10–5 molar solution of dibucaine; the percentage inhibition of benzoylcholine breakdown by the enzyme is the dibucaine number. Abnormal variants of cholinesterase are inhibited to lesser degrees, with dibucaine numbers less than the normal 75–85%. Thus useful in the analysis and typing of different abnormal variants, which may give rise to prolonged paralysis following suxamethonium administration.

Dichloroacetate, see Sodium dichloroacetate

Dichlorphenamide. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, used to treat glaucoma but also to stimulate respiration, possibly by lowering CSF pH. Actions are similar to those of acetazolamide, but longer lasting. Has been used to assist weaning in ICU.

Diclofenac sodium. NSAID, commonly used for postoperative analgesia, reducing opioid requirements. Also used for musculoskeletal pain and renal colic. Extensively (> 99%) protein-bound in plasma; half-life is 1–2 h. 60% excreted via urine, the rest passing into the faeces.

Dicobalt edetate, see Cyanide poisoning

Dicrotic notch, see Arterial waveform

Diethyl ether. C2H5OC2H5. Inhalational anaesthetic agent, first prepared in 1540. Paracelsus described its effects on chickens in the same year. Produced by heating concentrated sulphuric acid with ethanol. First used for anaesthesia in 1842 by Clarke and Long, who did not publish their work until later. Introduced publicly by Morton in the USA in 1846; used in London by Boott and in Dumfries in the same year. Classically given by open-drop techniques, and more recently using a draw-over technique (e.g. using the EMO vaporiser), or by standard plenum vaporiser. Inspired concentrations of up to 20% may be required during induction of anaesthesia.

Its many disadvantages include flammability, high blood/gas partition coefficient resulting in slow uptake and recovery, respiratory irritation causing coughing and laryngospasm, stimulation of salivary secretions, high incidence of nausea and vomiting, and occurrence of convulsions postoperatively, typically associated with pyrexia and atropine administration. Sympathetic stimulation maintains BP with low incidence of arrhythmias, but hyperglycaemia may occur.

Has been used in severe asthma because of its bronchodilator properties.

10–15% metabolised to alcohol, acetaldehyde and acetic acid.

Differential lung ventilation (DLV). Performed when the requirements of each lung are so different that conventional IPPV cannot maintain adequate gas exchange, e.g. because the poor compliance of one lung diverts the delivered tidal volume to the other, more compliant, lung. Thus reserved for when lung pathology is unilateral or much worse on one side, e.g. following aspiration of gastric contents or irritant substances, unilateral pneumonia, bronchopleural fistula. May be performed using two conventional ventilators, each connected to one lumen of a double-lumen endobronchial tube. The settings of each (including the ventilatory mode) are adjusted independently in order to achieve adequate lung expansion and gas exchange; synchronised inflation/deflation is usually not necessary, although sideways motion of the mediastinum (if one lung inflates just as the other deflates) may cause haemodynamic disturbance in susceptible patients. In some circumstances, it may be possible to ventilate the better lung whilst applying only CPAP to the diseased one.

Difficult intubation, see Intubation, difficult

Diffusing capacity (Transfer factor). Volume of a substance (usually carbon monoxide [CO]) transferred across the alveoli per minute per unit alveolar partial pressure. CO is used because it is rapidly taken up by haemoglobin in the blood; thus its transfer from alveoli to blood is limited mainly by diffusion across the alveolar membrane.

Reduction in pulmonary diseases (e.g. pulmonary fibrosis) has been traditionally attributed to increased alveolar membrane thickness, although  mismatch may be more important. Also reduced when alveolar membrane area is reduced, e.g. after pneumonectomy (corrected for by calculation of diffusing coefficient: diffusing capacity per litre of available lung volume).

mismatch may be more important. Also reduced when alveolar membrane area is reduced, e.g. after pneumonectomy (corrected for by calculation of diffusing coefficient: diffusing capacity per litre of available lung volume).

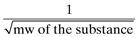

Diffusion. Movement of a substance from an area of high concentration to one of low concentration, resulting from spontaneous random movement of its constituent particles. May occur across membranes, e.g. from alveoli to bloodstream.

• Rate of diffusion across a membrane is proportional to:

For diffusion of a gas across a membrane into a liquid (e.g. across the alveolar membrane), concentration gradient is proportional to the pressure gradient, and is maintained if the gas is soluble in the liquid; i.e. rate of diffusion is proportional to solubility.

Diffusion hypoxia, see Fink effect

Digital nerve block. Each digit is supplied by two palmar and two dorsal digital nerves. A fine needle is introduced from the dorsal side of the base of the digit, and 2–3 ml local anaesthetic agent (without adrenaline) injected on each side, between bone and skin.

Digoxin. Most widely used cardiac glycoside, used to treat cardiac failure and supraventricular arrhythmias, e.g. AF, atrial flutter and SVT. Described and investigated by Withering in 1785 in his Account of the Foxglove. Slows atrioventricular conduction and increases myocardial contractility. Reduces hospitalisation rates and symptoms due to severe cardiac failure refractory to first-line treatment, but has no effect on mortality. Volume of distribution is large (700 litres) and half-life long (36 h); elimination is therefore lengthy after termination of treatment. Dosage must be reduced in renal impairment and in the elderly. Therapeutic plasma levels: 1–2 ng/ml (blood is taken 1 h after an iv dose, 8 h after an oral dose).

Contraindicated in Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome, since atrioventricular block may encourage conduction through accessory pathways with resultant arrhythmia.

• Dosage:

loading dose for rapid digitalisation:

loading dose for rapid digitalisation:

– 1.0–1.5 mg orally in divided doses over 24 h (250–500 mg/day if less urgent).

– 0.75–1.0 mg iv over at least 2 h. Fast injection may cause vasoconstriction and coronary ischaemia.

maintenance: 62.5–500 µg daily (usual range 125–250 µg).

maintenance: 62.5–500 µg daily (usual range 125–250 µg).

more common in hypokalaemia, hypercalcaemia or hypomagnesaemia.

more common in hypokalaemia, hypercalcaemia or hypomagnesaemia.

headache, malaise, confusion. Blurred or yellow discoloration of vision (xanthopsia) occurs early; the presence of hyperkalaemia suggests severe toxicity.

headache, malaise, confusion. Blurred or yellow discoloration of vision (xanthopsia) occurs early; the presence of hyperkalaemia suggests severe toxicity.

– prolonged P–R interval and heart block.

– T wave inversion.

– S–T segment depression (the ‘reverse tick’).

life-threatening arrhythmias and hyperkalaemia should be treated promptly with digoxin-specific antibody fragments. Potassium replacement may also be required. Electrical cardioversion may result in severe arrhythmias, and should be avoided. Magnesium is the drug of choice for digoxin-induced ventricular arrhythmias.

life-threatening arrhythmias and hyperkalaemia should be treated promptly with digoxin-specific antibody fragments. Potassium replacement may also be required. Electrical cardioversion may result in severe arrhythmias, and should be avoided. Magnesium is the drug of choice for digoxin-induced ventricular arrhythmias.

Dihydrocodeine tartrate. Opioid analgesic drug, of similar potency to codeine. Prepared in 1911. Causes fewer side effects than morphine or pethidine at equivalent analgesic doses. Also has a marked antitussive effect. Commonly used in combination with paracetamol as co-dydramol (500 mg/10 mg per tablet).

Diltiazem hydrochloride. Class III calcium channel blocking drug and class IV antiarrhythmic drug, used to treat angina and hypertension, especially when β-adrenergic receptor antagonists are contraindicated or ineffective. Causes vasodilatation and prolonged atrioventricular nodal conduction. Causes less myocardial depression than verapamil but may cause severe bradycardia. After single oral dosage, 90% absorbed but bioavailability is only 45% because of extensive first-pass metabolism. About 65% excreted via the GIT. An iv preparation is available in the USA for treatment of AF, atrial flutter and SVT.

Dilution techniques. Used for measuring body compartment volumes (e.g. blood, plasma, ECF and lung volumes). A known quantity of tracer substance is introduced into the space to be measured, and its concentration measured after complete mixing:

where C1 = initial concentration of indicator

C2 = final concentration of indicator

Tracer substances include dyes and radioisotopes; the latter may be injected as radioactive ions or attached to proteins, red blood cells, etc. Gaseous markers may be used to study lung volumes, e.g. helium to measure FRC.

The principle may be extended for cardiac output measurement, where radioisotope, dye or cold crystalloid solution is injected as a bolus proximal to the right ventricle, and its concentration measured distally, e.g. radial or pulmonary artery. A concentration–time curve is plotted to enable calculation of cardiac output. A double indicator dilution technique has been used to measure extravascular lung water.

Dimercaprol (BAL; British Anti-Lewisite). Chelating agent previously used in the treatment of heavy metal poisoning, especially antimony, arsenic, bismuth, mercury and gold. Now superseded by newer agents. Following im injection, peak levels occur within 1 h, with elimination in 4 h. Contraindicated in liver disease and glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.

[Lewisite – a potent arsenic-based chemical weapon used in World War II]

Dimethyl tubocurarine chloride/bromide. Non-depolarising neuromuscular blocking drug, derived from tubocurarine; introduced in 1948. More potent and longer-lasting (up to 2 h) than tubocurarine, and with less ganglion blockade and histamine release, i.e. more cardiostable. No longer used in the UK, although has been popular in the USA as metocurine. Almost entirely renally excreted.

Dinoprost/dinoprostone, see Prostaglandins

2,3-Diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG). Substance formed within red blood cells from phosphoglyceraldehyde, produced during glycolysis. Binds strongly to the β chains of deoxygenated haemoglobin, reducing its affinity for O2 and shifting the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve to the right, i.e. favours O2 liberation to the tissues. Binds poorly to the γ chains of fetal haemoglobin.

chronic hypoxaemia, e.g. in cyanotic heart disease.

chronic hypoxaemia, e.g. in cyanotic heart disease.

certain red cell enzyme abnormalities.

certain red cell enzyme abnormalities.

acidosis, e.g. in stored blood; requires 12–24 h for levels to be restored.

acidosis, e.g. in stored blood; requires 12–24 h for levels to be restored.

symptoms of upper respiratory infection.

symptoms of upper respiratory infection.

increasing malaise and fever. Diphtheria toxin may affect CNS, heart and other organs. Cranial nerve and peripheral nerve palsies, visual disturbances and cardiac failure with conduction defects and arrhythmias may occur.

increasing malaise and fever. Diphtheria toxin may affect CNS, heart and other organs. Cranial nerve and peripheral nerve palsies, visual disturbances and cardiac failure with conduction defects and arrhythmias may occur.

Dipipanone hydrochloride. Opioid analgesic drug, similar to methadone and dextromoramide. Prepared in 1950. Available in the UK for oral use as tablets of 10 mg combined with cyclizine 30 mg.

Diploma in Intensive Care Medicine (DICM). Instituted in 1997/8 to permit identification of doctors trained to an adequate standard to undertake a career with a large commitment to intensive care medicine in the UK. Aims to test knowledge and its application, and the ability to communicate with medical and nursing staff, patients and their relatives. Candidates for the Diploma must possess a postgraduate qualification in their primary specialty (e.g. FRCA, MRCP, FRCS), should have completed the stipulated periods of training (see Intensive care, training in), and must submit a dissertation. Replaced in 2013 by the Fellowship of the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine exam (FFICM).

Dipyridamole. Antiplatelet drug, used to prevent CVA and as an adjunct to oral anticoagulation, e.g. in patients with prosthetic heart valves. Modifies platelet aggregation, adhesion and survival. Also given iv for stress testing during diagnostic cardiac imaging; causes marked vasodilatation. May cause coronary steal.

Disaster, major, see Incident, major

Disequilibrium syndrome. Syndrome comprising nausea, vomiting, headache, restlessness, visual disturbances, tremor, coma and convulsions, associated with dialysis. More common in patients with pre-existing intracranial pathology, severe acidosis or uraemia. The cause is uncertain, although increased brain water is suggested by CT scanning. Rapid changes in osmolality or CSF pH have been suggested. Reduced by gradual institution of dialysis, especially if plasma urea is very high, and by careful management of sodium balance. Management is supportive.

Disinfection of anaesthetic equipment, see Contamination of anaesthetic equipment

Disodium pamidronate, see Bisphosphonates

Disopyramide phosphate. Class Ia antiarrhythmic drug, used to treat SVT and VT. Half-life is 7 h.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Pathological activation of coagulation by a disease process, leading to fibrin clot formation, consumption of platelets and coagulation factors (I, II and XIII), and secondary fibrinolysis. May be precipitated by shock, sepsis, haemolysis, malignancy, trauma, burns, major surgery, PE, extracorporeal circulation and obstetric conditions, e.g. pre-eclampsia, amniotic fluid embolism, intrauterine death and placental abruption.

• Effects:

may occur chronically, with little clinical abnormality.

may occur chronically, with little clinical abnormality.

bruising, bleeding from wounds, venepuncture sites, GIT, lung, urinary tract and uteroplacental bed.

bruising, bleeding from wounds, venepuncture sites, GIT, lung, urinary tract and uteroplacental bed.

capillary microthrombosis may cause multiple organ failure.

capillary microthrombosis may cause multiple organ failure.

shock, acidosis and hypoxaemia may occur.

shock, acidosis and hypoxaemia may occur.