Cytomegalovirus

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

• Discuss the etiology and epidemiology of acquired, latent, and congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection.

• Explain the signs and symptoms of acquired and congenital CMV infections.

• Describe the immunologic manifestations of CMV.

• Identify and explain the serologic markers and diagnostic evaluation of CMV.

• Discuss the principles and applications of passive latex agglutination and other quantitative determinations of IgM and IgG antibodies.

• Correctly answer case study related multiple choice questions.

• Be prepared to participate in a discussion of critical thinking questions.

• Describe the principle, reference range, sources of error, limitations, and clinical applications of Latex Agglutination for Antibodies to CMV.

• Describe the principle and clinical applications of antibody detection to CMV.

Signs and Symptoms

Acquired Infection

1. Primary infection occurs when a previously unexposed (seronegative) recipient is transfused with blood from an actively or latently infected donor. This type of infection is accompanied by the presence of virus in the blood and urine, an immediate antibody response, and eventual seroconversion. Patients with primary infections may be symptomatic, but the great majority are asymptomatic.

2. Reactivated infection can occur when a seropositive recipient is transfused with blood from a CMV antibody–positive or –negative donor. Donor leukocytes are thought to trigger an allograft reaction, which in turn reactivates the recipient’s latent infection. These infections may be accompanied by significant increases in CMV-specific antibody. Some reactivated infections exhibit viral shedding as their only manifestation. Reactivated infections are largely asymptomatic.

3. Reinfection can occur by a CMV strain in the donor’s blood that differs from the strain that originally infected the recipient. A significant antibody response is observed and viral shedding occurs. Although it is difficult to differentiate a reactivated infection if the patient and donor are CMV antibody–positive before transfusion, reinfections can be documented if isolates can be obtained from the donor and recipient.

Congenital Infection

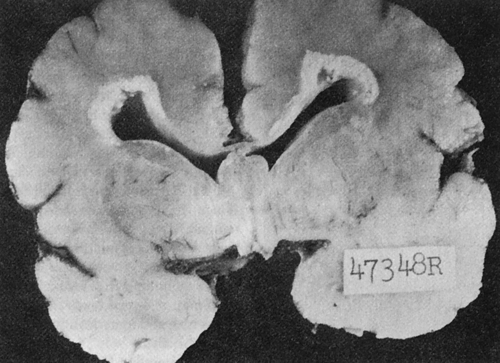

The classic congenital CMV syndrome is manifested by a high incidence of neurologic symptoms, as well as neuromuscular disorders, jaundice, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly (Fig. 21-1). Petechia is the most common clinical sign, seen in about 50% of CMV-infected infants.

Congenitally infected newborns, especially those who acquire CMV during a maternal primary infection, are more prone to develop severe cytomegalic inclusion disease (CID). The severe form of CID may be fatal or can cause permanent neurologic sequelae, such as intracranial calcifications (Fig. 21-2), mental retardation, deafness, vision defects, microcephaly, and motor dysfunction. Psychomotor impairment is seen in 51% to 75% of survivors. Hearing loss is observed in 21% to 50% and visual impairment in 20% of patients. Infants without symptoms at birth may develop hearing impairment and neurologic impairment later.

Immunologic Manifestations

Immune System Alterations

Serologic Markers

The characteristic antibody responses associated with infection are as follows:

• Primary infection, demonstrated by a transient virus-specific IgM antibody response and eventual seroconversion to produce immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to the virus.

• Reactivation of latent infection in seropositive (IgG) individuals, which may be accompanied by significant increases in IgG antibodies to the virus, but elicits no detectable IgM response.

• Reinfection by a strain of CMV different from the original infecting strain. A significant IgG antibody response is demonstrated. It is not known whether an IgM response occurs.

Laboratory Evaluation

In immunocompromised patients, CMV serology is not recommended. The preferred method for diagnosis is culture of virus and/or polymerase chain reaction (PCR). A variety of methods can be used for screening purposes (Table 21-1).

Table 21-1

Laboratory Diagnosis of Cytomegalovirus Infection∗

| Method | Test Method | Recommended Use |

| CMV rapid culture | Cell culture, immunofluorescence | Rapid diagnosis of CMV infection Gold standard test for tissue |

| CMV by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Blood, bone marrow, amniotic fluid |

Qualitative PCR | Rapid test for diagnosing CMV in immunocompromised patients or solid organ donors. Amniotic fluid from a fetus of >21 weeks gestation can be analyzed. |

| CMV PCR | Quantitative PCR | Diagnose CMV infection. Monitor disease state in solid organ transplant and HIV patients. |

| CMV antibodies: IgM and IgG | Latex agglutination | Screen pregnant women and infants possibly infected with CMV. Infants may test positive during first 6 months due to maternal antibodies. Discriminate between current (IgM) and prior infections (IgG). |

| CMV antibodies: total | Solid-phase agglutination | Screen organ donors. |

| CMV by immunohistochemistry | Immunohistochemistry | Histologic diagnosis of CMV based on tissue from affected site |

ELISA, Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

∗A negative result (<2.6 log copies/mL, or <390 copies/mL) does not rule out the presence of PCR inhibitors in the patient specimen or CMV nucleic acid in concentrations below the assay’s level of detection. Inhibition may also lead to underestimation of viral quantitation.

Adapted from Associated Regional and University Pathologists (ARUP) Laboratories: ARUP’s laboratory test directory, 2012 (http://www.aruplab.com/guides).

infants complicates the interpretation of serologic results during the first 6 months of life because the antibody may be maternal in origin.

Passive Latex Agglutination for Detection of Antibodies to Cytomegalovirus

Passive Latex Agglutination for Detection of Antibodies to Cytomegalovirus

Principle

The CMVscan Card Test∗ is a passive latex agglutination test for the detection of IgM and IgG CMV antibodies. It can be used as a diagnostic tool or to screen donor specimens for antibodies to CMV in human serum and plasma. This assay can be performed qualitatively on undiluted serum to identify antibodies to CMV and quantitatively using serial twofold dilutions to determine the titer of CMV antibody.

The procedural protocol is posted on the ![]() website.

website.

Limitations

Several limitations are inherent in CMV antibody detection, as follows:

1. Patients with acute infection may not have detectable antibody.

2. Seroconversion may indicate recent infection, but an increase in antibody titer by this method does not differentiate between a primary and secondary antibody response.

3. The timing of antibody responses during a primary infection may differ slightly. The pattern of antibody response during a primary CMV infection has not been demonstrated.

4. Test results from neonates should be interpreted with caution because the presence of CMV antibody is usually the result of passive transfer from the mother to the fetus.

5. Although the CMV latex procedure will detect IgM and IgG antibodies, detection of IgA and IgE antibodies has not yet been demonstrated.

Chapter Highlights

• Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a herpesvirus. All the herpesviruses are relatively large, enveloped DNA viruses that undergo a replicative cycle involving DNA expression and nucleocapsid assembly within the nucleus. Although the herpesvirus family causes various clinical diseases, herpesviruses share the basic feature of being cell-associated.

• CMV may produce subclinical infections that can be reactivated under appropriate stimuli. Dissemination of the virus may occur by the oral, respiratory, or venereal route, as well as parenterally by organ transplantation or by transfusion of fresh blood.

• The incidence of primary CMV infections during childhood is low. Patients at highest risk of mortality from CMV infections are allograft transplant, seronegative patients who receive tissue from a seropositive donor. Most of these infections are transmitted by the donor organ or from reactivation of the recipient’s latent virus.

• Transmission of CMV through transfusion of blood and blood components containing WBCs is increasingly important in immunocompromised patients who require supportive therapy. Low birth weight neonates are also at high risk from CMV infections from infected blood products.

• Persistent infections characterized by periods of reactivation of CMV (latent infections) have not been clearly defined for CMV.

• CMV is a major cause of congenital viral infections in the United States because primary and recurrent maternal CMV infections can be transmitted in utero.

• In CMV-infected cells, antigens appear at various times after infection, before the replication of viral DNA. Immediate-early antigens appear within 1 hour of cellular infection and early antigens within 24 hours. At about 72 hours or the end of the viral replication cycle, late antigens appear.

• The presence of antibodies against immediate-early and early antigens is associated with active infection, primary or reactivated. The following characteristic antibody responses are associated with CMV infection:

• Primary infection is demonstrated by a transient, virus-specific IgM antibody response and eventual seroconversion to produce IgG antibodies to the virus.

• Reactivation of latent CMV infection in seropositive (IgG) individuals may be accompanied by a significant increase in IgG antibodies to the virus, but no detectable IgM response.

• Reinfection by a different CMV strain than the original infecting strain results in a significant IgG antibody response but unknown IgM response.

• Serologic methods (e.g., EIA) to detect CMV-specific IgM can represent primary infection or rare reactivation. Detection of significant increases in CMV-specific IgG antibody suggest, but do not prove, recent infection or reactivation of latent infection.