12 Cysts and Lipomas

Epidermal Inclusion Cysts and Variants

Epidermal inclusion cysts arise from a plugged follicular opening, resulting in a nodular cyst filled with cheesy malodorous keratin material. These are also commonly and incorrectly called sebaceous cysts but do not in fact contain any sebum. Unfortunately, the ICD code for these cysts is named “sebaceous cyst” so you must know this misnomer for billing purposes. Other names include infundibular cysts, keratinous cysts, and epidermoid cysts. Generally, these present as a compressible but nonfluctuant nodule, which can be diagnosed clinically due to a comedo-like central punctum that can be distinguished at the apex (Figure 12-1). Because the keratin material inside the cyst wall is highly inflammatory, any cyst that has ruptured can spark a vigorous inflammatory response that can be mistaken for cellulitis (Figure 12-2). Even if these do become superinfected, the treatment of choice is incision and drainage to remove the inflammatory and/or infected contents.

FIGURE 12-1 An epidermal inclusion cyst with a central punctum that looks like an open comedone.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

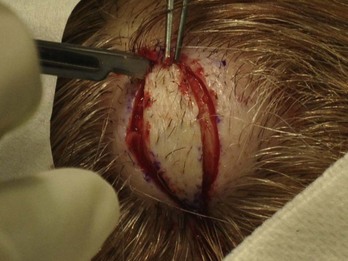

Pilar cysts (also known as trichilemmal cysts and commonly called wens) are very similar to epidermal inclusion cysts with the exception that the capsule is much thicker and the location generally on the scalp (Figures 12-3 and 12-4). Pilar cysts rarely have a punctum but the thickness of the capsule makes removal somewhat easier. These can also become very large but in most cases they are 5 to 20 mm in size. It is not unusual for the hair to become thinned or actually stop growing over the cyst (Figures 12-3 and 12-4).

FIGURE 12-3 A typical presentation of a pilar cyst (trichilemmal cyst or wen) on the scalp.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

One variant of the epidermal cyst is the milium cyst. Milia are histologically identical to classic epidermal cysts but only grow to 1 to 2 mm. They are generally located around the eyes and central portion of the face (See Figure 33-20 in Chapter 33, Procedures to Treat Benign Conditions).

Cysts can be located almost anywhere but are common on the trunk, neck, face, and behind the ears. They range in size from millimeters to centimeters. Epidermal inclusion cysts are benign; however, there are rare proliferating epidermal inclusion cysts that can become carcinogenic. Any cyst that does not look 100% typical on excision should be sent to the pathologist. A full differential diagnosis is given in Box 12-1.

FIGURE 12-8 Hydrocystoma around the eye. It is benign and has a very thin wall that is easy to cut.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

FIGURE 12-12 A thyroglossal duct cyst in a young girl. Note how it is midline. These will move up with swallowing.

(Courtesy of Frank Miller, MD.)

The occurrence of multiple true sebaceous cysts at a younger age is termed steatocystoma multiplex, which is a genetically inherited problem. These capsules are extremely thin. Small fluid-filled very thin-walled cysts around the eyes are called hidrocystomas (Figure 12-10).

FIGURE 12-10 Digital mucous (myxoid) cyst on the finger. They are most commonly found distal to the DIP joint.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Contraindications for Cyst Removal

Minimal Excision Technique

Advantages

Advantages of the minimal excision technique for the clinician include the following:

Disadvantages

Disadvantages of the minimal excision technique for the clinician include:

Disadvantages for the patient include:

Be aware that this procedure is more difficult where the skin is very thick such as on the back.

Minimal Excision Technique: Steps and Principles

Preoperative Measures

Performing the Procedure

FIGURE 12-18 A small emptied cyst is pulled through a small punch opening and freed from underlying tissue using an iris scissor.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

FIGURE 12-19 Pulling a large emptied cyst wall through the opening created by an ellipse in the abdominal wall.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Pathology

Benign-appearing typical cysts do not need to be sent to the pathologist. If a solid tumor is found, or if there is any irregularity about the procedure or uncertainty about the diagnosis, send the specimen. Note the possible differential diagnoses in Box 12-1.

Alternatives to the Minimal Excision Technique

A couple of alternatives to the minimal excision technique are worth discussing.

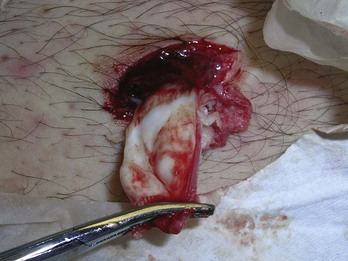

Elliptical Excision

Full elliptical excisions are covered in Chapter 11. This technique may be a good option if cysts have been heavily manipulated or have recurred. One approach is to avoid cutting into the cyst wall and attempting to remove the cyst whole. Another approach is similar to the minimal cyst removal in which the cyst is cut on purpose and the contents are evacuated to allow the cyst to be removed through a smaller ellipse. If the cyst is large and elevated, make sure the width of the ellipse is equal to the width of the cyst to avoid dog ears (standing cones).3 This is especially true with large protuberant pilar cysts (Figure 12-22). The scalp will not lay flat unless the ellipse is as long as the cyst. The elliptical excision method is preferred with any large protuberant cysts that would leave redundant skin if the cyst is excised through a punch or a linear incision.

Incision and Drainage Plus Iodine Crystals

One alternative consists of a combination incision and drainage (I&D) of the cyst followed by placing two iodine crystals in the center of the cyst. Over a period of several days, the cyst will harden and darken. This may then be expressed through the skin on the return visit. This is a fairly simple technique with similar cosmetic results to the minimal excision technique. It does however, require a follow-up visit and some patience as the cyst darkens and hardens. Iodine crystals USP are available from the pharmacy. The size used is dependent on the size of the cyst. It works well for cysts up to about 2 cm.2

Incision and Drainage of Inflamed and Infected Cysts

When patients present with an acutely inflamed or possibly infected cyst, the treatment is to incise, drain, and pack the wound. The same principles apply as those described in Chapter 17, Incision and Drainage. Use a ring block for anesthesia and a No. 11 blade scalpel to incise the inflamed area. Because the incision will be packed and not closed, clean technique is adequate. Antibiotics are rarely beneficial because the majority of these inflammatory changes are due to a reaction to the ruptured contents rather than a true infection. Antibiotics are not needed especially after an I&D, nor are cultures. Some clinicians may want to culture and use antibiotics in immune-suppressed patients, but even then the definitive treatment is I&D.

Hidrocystomas

Hidrocystomas (Figure 12-10) can be easily excised using pickups and cutting a small thin ellipse over the cyst with a sharp tissue scissor. The fluid will drain out easily. There should be little bleeding so pressure alone should be adequate for hemostasis.

Dermoid Cysts

Be aware of the precautions cited earlier. If a dermoid cyst (Figure 12-13) is suspected, excisional removal is indicated. If a dermoid cyst is found on the face of a young child, refer for removal under sedation or general anesthesia.

Lipomas

Lipomas can usually be diagnosed clinically, although the differential diagnosis includes many of the same entities discussed for cysts (Box 12-1). Additional considerations are hematoma, panniculitis, rheumatic nodules, and metastatic cancer. Rapidly growing subcutaneous masses should be removed and sent for pathology. Several approaches are used to remove lipomas: incision and expression, elliptical excision, and liposuction.

Contraindications for Lipoma Removal

There are no contraindications other than patient preference to leave superficial lipomas alone.

General Considerations

Liposarcomas can appear similar to lipomas, but do not arise from lipomas. In the case of some worrisome lesions, first consider needle aspiration or imaging.4,5 However, a full excision will always give the best sampling of the lesion to the pathologist.

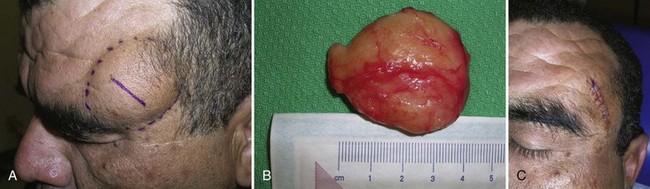

Anatomic considerations are important as well. Lesions that present in the sacroiliac region can occasionally communicate with the spinal column. Here, consider consulting with neurosurgery or ruling out nerve involvement by obtaining an MRI. Also of note, lipomas on the forehead can track behind the fascial plane and under the frontalis muscle. Forehead lipomas are frequently removed in the office but contrary to most other lipomas, are not as discrete and thus are more difficult to remove (Figure 12-23). On exam they will generally feel larger than they actually are, causing the surgeon to question if the lesion was really removed. Despite these caveats, lipoma excisions are generally straightforward.

Preoperative

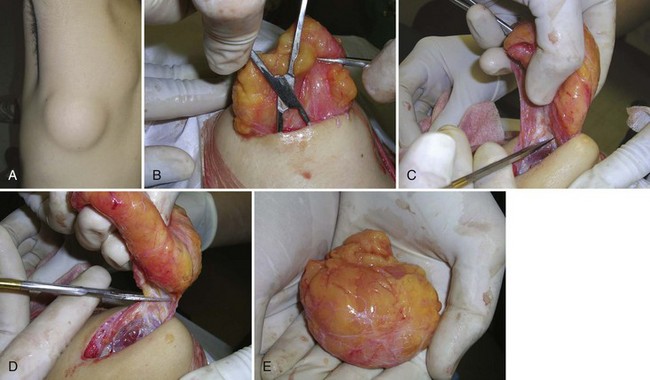

Incision and Pressure Method

The easiest method to remove lipomas is the incision and pressure method. Draw out the linear incision so that it is approximately one-third to one-half the diameter of the lipoma (Figure 12-24A). Make a linear incision through the skin over the top of the lipoma. Hold the No. 11 blade perpendicular to the skin and cut through the skin into the lipoma with a sawing motion. Fortunately, lipomas are relatively avascular so little bleeding should be encountered. If there is much bleeding, reassess the diagnosis and procedure immediately.

Once the incision has been made, insert and spread the curved hemostats around the edge of the lipoma to break up the fibrous bands that attach it to the surrounding tissue. Do this through 360 degrees and try to get under the lipoma as well. Then express the lipoma through the incision using digital pressure (Figure 12-24B). If this does not work, use the hemostat again to free the lipoma further. If this still does not work, consider extending the incision on both sides to give more room for the lipoma to come out. Pulling the lipoma with the hemostat clamped on it can help while an assistant is squeezing the lipoma out from below with digital pressure.

Once the lipoma is out, see if it appears whole and explore the cavity to make sure the entire lipoma has been removed. Bleeding should be nonexistent to minimal. Hold pressure on the defect to express any blood or fluid. The incision can be closed with simple interrupted sutures or subcuticular sutures. If the defect is large consider placing some deep sutures to close dead space (see Chapter 6, Suturing Techniques). Some clinicians use Steri-Strips with no sutures underneath a pressure dressing. With experience and efficient office staff, this procedure can be done in 10 minutes. Even a large lipoma can be removed using this method (Figure 12-25).

Examination and Pathology

Inspect the lipoma and feel it between your fingers. It should be a contiguous yellow mass without significant vascularity or calcifications (Figure 12-25E). Any hint of abnormality or odd behavior of the tissue during the procedure should prompt you to send the specimen for pathology. Any lesions with significant vascularity, size, calcifications, or other worrisome features should be sent to pathology to confirm a benign diagnosis.

Punch (Enucleation) Technique

Removing the Lipoma

Elliptical Excision of A Lipoma

A true elliptical excision for removal can be practical for larger lipomas or those under thick skin (back of the neck, posterior trunk) and with lesions that are of uncertain diagnosis or unusually firm. The elliptical excision is covered fully in Chapter 11. It may be more helpful to leave the elliptical piece of skin attached to the dermis and use the skin as a convenient handle to manipulate the lipoma with a hemostat, clamp, or forceps. The scar will be larger using this technique, but in some instances that is not a concern.

Digital Mucous (Myxoid) Cysts

Digital mucous cysts or myxoid cysts are similar to ganglia but arise on the distal fingers and occasionally toes (Figures 12-27 and 12-28). These are the most common cysts on the hand and are benign. The exact etiology is uncertain, but the cysts likely form from the mucoid degeneration associated with arthritis. Cysts usually present after the fifth decade of life, but can present earlier when associated with arthropathy such as rheumatoid arthritis. The most common location is the distal interphalangeal joint, on the dorsal aspect. Lesions that occur in the proximal nail fold can distort the lunula, put pressure on the matrix, and cause nail deformities and pain (Figure 12-28).

When treatment is sought, options range from observation to joint surgery with osteophyte removal and flap reconstruction. In the office setting, the most common options are draining with repeat sterile needling and cryotherapy.1,2 Alternatives include the injection of sclerosing agents, steroid injections, or excision with flap repair. All options risk recurrence with radical joint surgery as the most definitive and most costly option.

Needling and Cryotherapy

Alternatives to Cryotherapy

Minami et al.7 described a method of cryotherapy that involved direct contact with a probe or liquid nitrogen–soaked cotton tipped swab applied over a thin plastic film after the pseudocyst had been drained. Presumably this prevented cotton contents from adhering to the tissue. After a median of 2.64 treatments, they had an 85% to 92% cure rate.

Another very good alternative is serial needling. This can be done in the office or at home by a capable patient who is given sterile needles. The success rate is 70% with minimal expense aside from office visits.8 Another option is excision of the cyst in the office with a small rotation flap pinned with two small sutures. This requires a digital block and a surgical tray, but the long-term cure rate may rival joint surgery.9 A similar but simpler technique was described wherein a three-sided or fingertip-shaped pedicle is created around the cyst and undermined—creating a small flap. Then, instead of rotating or transposing the cyst containing flap, tack it back down with one or two sutures. The scarring that forms theoretically blocks a path from the joint space to the cyst.10

Coding and Billing Pearls

Lipomas may also be coded with the new 2010 CPT codes for excision of a subcutaneous tumor based on anatomic location. Some coders advocate using these codes only for deep lipomas including those under fascia or under muscle. Other coders state that all lipomas should be coded with these codes. See Table 38-13 in Chapter 38, Surviving Financially, for the specific soft tissue tumor codes based on location of the lipoma. The most commonly needed codes for lipomas are listed in Table 12-1. These soft tissue tumor codes are all inclusive. Neither the length of the incision nor the type of repair that is used matter. The large lipoma in Figure 12-25 was deep based on the visibility of the latissimus dorsi muscle at the time of excision and could easily be coded as 21931. If a decision is made to code it as a skin lesion (an acceptable alternative), then the code used would be 11446 for a benign skin lesion excised with a diameter over 4.0 cm. Both coding methods pay well and are considered legitimate for the procedure performed. The specific ICD-9 codes for lipomas are 214.0 for the face and 214.1 for other areas.

TABLE 12-1 Subcutaneous Soft Tissue Tumor Excisions (Including Lipomas)

|

CPT |

Description |

2010 National Medicare Reimbursement |

|---|---|---|

| 21930 | Back or flank, <3 cm | 430 |

| 21931 | Back or flank, ≥3 cm | 459 |

| 24071 | Upper arm or elbow, <3 cm | 395 |

| 24075 | Upper arm or elbow, ≥3 cm | 441 |

| 25071 | Forearm and/or wrist, <3 cm | 341 |

| 25075 | Forearm and/or wrist, ≥3 cm | 414 |

| 21011 | Face or scalp, <2 cm | 306 |

| 21012 | Face or scalp, ≥2 cm | 328 |

1. Diven DG, Dozier SE, Meyer DJ, Smith EB. Bacteriology of inflamed and uninflamed epidermal inclusion cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:49-51.

2. Zuber TJ. Minimal excision technique for epidermoid (sebaceous) cysts. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:1409-1412. 1417–1418, 1420

3. Suliman MT. Excision of epidermoid (sebaceous) cyst: description of the operative technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:2042-2043.

4. Pandya KA, Radke F. Benign skin lesions: lipomas, epidermal inclusion cysts, muscle and nerve biopsies. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89:677-687.

5. Serpell JW, Chen RY. Review of large deep lipomatous tumours. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:524-529.

6. Chandawarkar RY, Rodriguez P, Roussalis J, Tantri MD. Minimal-scar segmental extraction of lipomas: study of 122 consecutive procedures. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:59-63. discussion 63–64

7. Minami S, Nakagawa N, Ito T, et al. A simple and effective technique for the cryotherapy of digital mucous cysts. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1280-1282.

8. Epstein E. A simple technique for managing digital mucous cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1315-1316.

9. Crawford RJ, Gupta A, Risitano G, Burke FD. Mucous cyst of the distal interphalangeal joint: treatment by simple excision or excision and rotation flap. J Hand Surg. 1990;15:113-114.

10. Lawrence C. Skin and osteophyte removal is not required in the surgical treatment of digital mucous cysts. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1560-1564.