Chapter 12 Cystic Pancreatic Lesions

Introduction

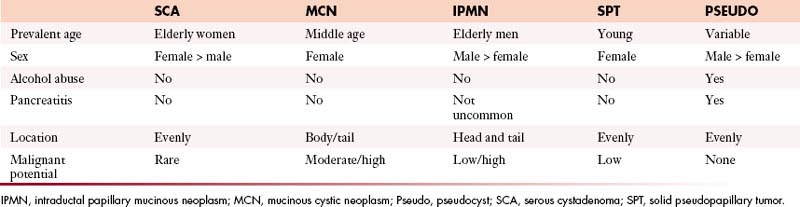

Cystic lesions of the pancreas include malignant and benign processes and may or may not cause clinical symptoms. Most of these lesions are seen incidentally on cross-sectional imaging and can be of various sizes. The risk of malignancy in a symptomatic cyst can be high, whereas asymptomatic cysts can be benign, malignant, or premalignant. Pancreatic cystic neoplasms account for 10% to 15% of pancreatic cysts, less than 1% of primary pancreatic malignancies.1

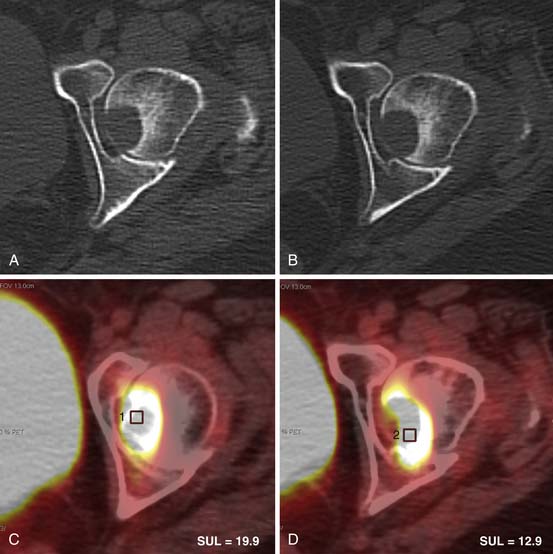

Currently, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used in assessment of pancreatic cystic lesions. CT is more widely available because it requires less scan time and is the most accessible and, hence, is more commonly used. MRI is able to identify communication of the cystic lesion with the main pancreatic duct, although with currently available thin-section imaging, CT has a similar ability.2 Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG)–positron-emission tomography (PET)/CT has been used to differentiate a malignant from a benign cystic lesion depending on its metabolic activity.3

CECT and MRI is not operator-dependent and can visualize the entire pancreas without difficulty. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is operator- and patient-dependent, and EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) has a complementary role in this difficult task by providing additional real-time assessment and cystic content for further analysis. Equipped with a Doppler device, it allows tissue sampling by FNA avoiding the major vessels. PET/CT is an evolving modality for detecting malignancy in cystic pancreatic lesions. It has been shown to detect invasive cancer in a cystic lesion; however, it cannot identify carcinoma in situ.3 This modality can help detect distant metastases in the setting of invasive cancer.4 Pancreatic cystic lesions may be identified at transabdominal US. However, it is limited in patients with large body habitus, and overlying bowel gas may obscure the lesions. Calcifications within the lesion are better seen on the CECT; septations may or may not be well seen depending on the size of the lesion and thickness of the septations. MRI is able to identify septations better as well as the contents of the cyst fluid if they are hemorrhagic; however, detection of mucin is equivocal. Even incidentally found cystic lesions of the pancreas should undergo diagnostic evaluation regardless of size. EUS can be used to evaluate the cyst, and concomitant cytologic analysis of cyst fluid can be obtained by EUS-FNA. The pancreatic cyst fluid analysis should include staining for mucin and measurement of cyst fluid amylase, lipase, and various tumor markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA).

Pseudocysts make up the majority of all cystic lesions of the pancreas, the rest comprise cystic tumors and true cysts. Hydatid cysts of the pancreas are rare and should be considered as a differential diagnosis of a cystic pancreatic lesion in countries where this disease is endemic.5 Pancreatic primary cystic tumors fall into one of three major groups: serous tumors (including SCA and cystadenocarcinoma), mucinous tumors (including mucinous cystadenomas, mucinous cystadenocarcinomas, intraductal papillary adenomas, and intraductal papillary adenocarcinoma) and solid pseudopapillary tumors (SPTs). The majority of cystic pancreatic tumors are asymptomatic and slow-growing. When the patients are symptomatic, the symptoms are caused by mass effect that is usually vague and poorly localized. Intraductal papillary mucinous tumors (IPMTs) may present with pain that may mimic chronic pancreatitis.6 On cross-sectional imaging, they can be characterized as simple, containing no internal nodularity, or complex, containing internal septations or mural nodules. They can also be classified as unilocular and multilocular depending on the number of locules present.

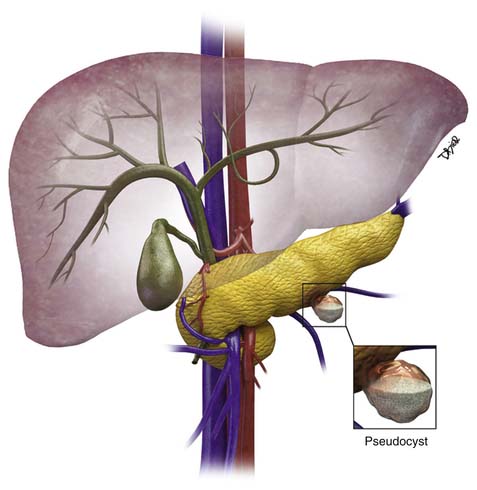

I Pancreatic Pseudocysts

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The majority of cystic lesions found in the pancreas are pseudocysts and they account for 70% of all cystic lesions.7 They lack an epithelial lining and have a fibrous capsule. Pancreatic pseudocysts occur after an episode of pancreatitis and are caused by leakage of pancreatic enzymes, such as amylase and lipase, which cause fat necrosis and hemorrhage owing to erosion of adjacent vessels.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with pancreatitis may present with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or sepsis due to infection or obstructive jaundice.8 Because there is leakage of pancreatic enzymes, fistulation into nearby structures, such as the common bile duct, esophagus,9,10 and pleura,11 can occur. The pancreatic pseudocysts seldom demonstrate internal hemorrhage, however this finding is associated with increased mortality. The pseudocysts can erode the adjacent vessels and cause pseudoaneurysms, which may rupture, leading to hemorrhage. The most common arteries involved are the splenic, gastroduodenal, and superior pancreaticoduodenal.12 Pseudocysts are commonly seen in males and usually are seen in alcoholics or can be associated with abdominal trauma.13

Imaging

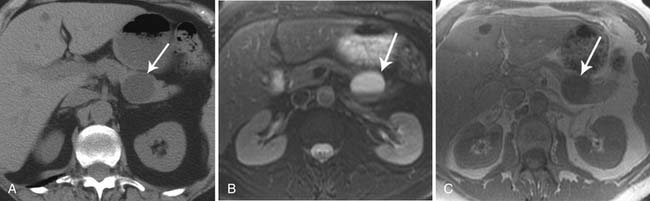

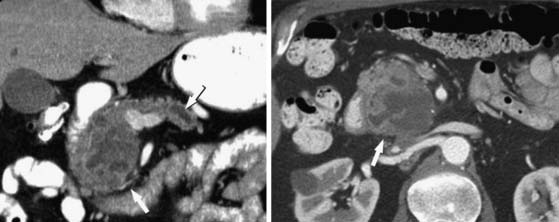

Pseudocysts (Figures 12-1 and 12-2) on cross-sectional imaging usually appear as unilocular lesions, without internal septations or mural nodules. They do communicate with the main pancreatic duct.7 These cysts on imaging have an irregular wall in the early stages, but tend to evolve and become well marginated.14 On CECT, pseudocysts look like a fluid collection, which may either have an imperceptible wall or a thick wall that may or may not show enhancement since it is made of fibrous tissue.14 On MRI, pseudocysts may have a high signal on T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) due to blood products. On magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), they may show communication with the main pancreatic duct. On US, they may appear as thin-walled unilocular anechoic masses with increased through transmission. Complicated cysts may have low-level internal echoes with a fluid debris level or can have internal septations. If calcification is present within the wall of the cyst, it may obscure the cyst. They do not have enhancing nodules, and if present, one must consider a mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN) in the differential. One clue that can be seen on CT or MRI is peripancreatic stranding, which is considered the hallmark of pancreatitis and, when associated with a cystic lesion, is suggestive of a pseudocyst.

II Simple Cysts

Epidemiology and Risk Factor

True cystic lesions of the pancreas are common,4,15 are lined by epithelium, and can be seen in patients with von Hippel–Lindau (vHL) disease,16 cystic fibrosis, and polycystic kidney disease. These cysts have a similar imaging appearance to the simple cysts seen in the liver and the kidneys.15

Imaging

On CT, they have Hounsfield unit (HU) values of fluid. On MRI, they have a high signal on the T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) and a low signal on T1WI and do not show enhancement. They do not have mural nodules. On US, they are anechoic with posterior acoustic enhancement. The differential of these cysts includes MCN because there is no distinguishing radiologic finding between the two. When these cysts are larger than 3 cm, EUS can be performed and a biopsy can be obtained to determine the cystic contents and exclude a mucinous neoplasm; these cysts are not usually resected.

III Mucinous Non-neoplastic Cyst

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Mucinous non-neoplastic cysts (MNCs) are common cystic tumors of the pancreas first described in 2002 by Kosmahl and coworkers.17 The cause and the development of MNCs are not known. It may be speculated that they are caused by a developmental defect of the pancreas, resulting in a focal cystic transformation of the duct system.

Pathology

MNCs are lined by tall columnar epithelium, which secretes mucin.18 Their maximum diameter ranges from 3 to 12 cm, they may be either unilocular or multilocular, and they may be filled with turbid or bloody fluid.17 These tumors do not have an ovarian stroma, which is a characteristic of mucinous cystadenomas. These cysts also do not communicate with the main pancreatic duct, do not show cellularity or have papillary projections as seen in IPMNs, and are believed to be benign.17

Imaging

On imaging, MNCs (Figure 12-3) are usually small and unilocular, with thin septa. On MRI, they have a signal intensity of simple fluid; on CECT, their HU is less than 20. On imaging, the appearance of MNCs cannot be easily differentiated from that of mucinous cystadenomas, especially if the mucinous cyst is large or has a thick wall. One of the important distinguishing factors is that the mucinous cystadenomas are commonly seen in females, whereas the MNCs have no gender predilection.19 If these cysts are larger than 2 cm, EUS-FNA can be performed and the cyst contents can be differentiated from those of other mucinous cystic neoplasms on immunohistochemical staining (Table 12-1).

Treatment

Usually MCNs do not require treatment unless they become symptomatic owing to internal hemorrhage or cause biliary obstruction, which is rare.17

Surveillance

If present in the head of the pancreas, they can cause ductal obstruction and can be followed at different intervals depending on size.

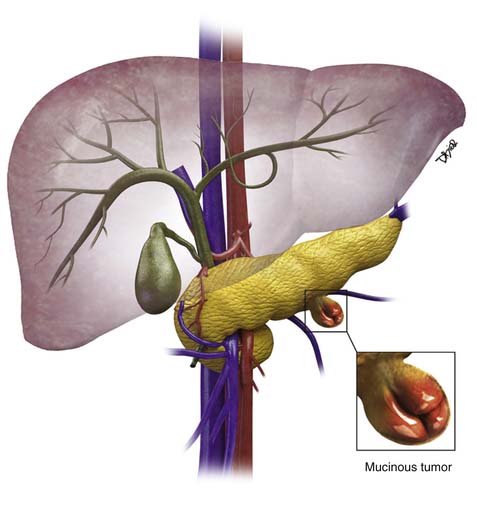

Anatomy and Pathology

MCNs (Figure 12-4) are generally found in the body and tail of the pancreas, they are usually solitary, and their size ranges from 6 to 35 cm.20 They are lined with an inner layer of cells that secrete mucin and an outer layer of cells that resemble the ovarian stroma.4,21 They have several locules and a thick wall.6 These tumors do not communicate with the main pancreatic duct unless they erode into the duct, causing a fistula.6,22 The number of locules are fewer than six and the size of the locules is generally greater than 2 cm. They may contain watery fluid or hemorrhagic, necrotic, or mucinous material. These tumors usually have intramural nodules, which histologically may range from high-grade dysplasia to invasive carcinoma.22 MCNs resemble the MCNs of the ovary and are exclusively seen in women of reproductive age (>95%) with a mean age of 45 years, and are typically present in the body or tail of the pancreas.19,20,22,23 Curvilinear calcifications may be noted in the periphery of the tumor and/or capsule in 10% to 25% of cases.14

Clinical Presentation

They may present with vague abdominal discomfort and have symptoms such as weight loss and anorexia.

Imaging

On cross-sectional imaging, these tumors may appear as a single large cyst or a large cyst with multiple locules with a thick outer wall, thick septations, and enhancing intramural nodules. Sometimes, calcification of the outer wall can be seen6; the outer wall of the cyst may enhance on the delayed phase, a finding that correlates with a fibrotic capsule seen on histopathology. On MRI, the fluid within the cyst may have a low signal on the T1WI and a high signal on the T2WI. However, increased signal on the T1WI has been observed owing to presence of mucin,24 but unfortunately, this is unreliable. The presence of enhancing nodules should raise the suspicion for malignancy.23

On ultrasound, MCNs (Figure 12-5) can appear as well-demarcated, anechoic, thick-walled cystic masses and may have echogenic thick septa, internal nodularity, or mural calcification. Differential diagnosis of these lesions include a pseudocyst; however, they can be differentiated on serial follow-up imaging in which the pseudocyst may decrease in size whereas the mucinous neoplasm usually persists.

Anatomy and Pathology

These masses are usually seen in the body and the tail of the pancreas. The patients with invasive mucinous carcinoma are older than those with noninvasive mucinous cystadenoma; this finding is suggestive of a progression from cystadenoma to cystadenocarcinoma.20 The earliest genetic change seen within MCNs is the mutation of the KRAS2 oncogene located on chromosome 12p25 and is present in 90% of the MCNs with carcinoma in situ.25 MCNs have a progression toward malignancy that is similar to that of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia.25

Clinical Presentation

These may present with vague abdominal pain and discomfort and, rarely, can cause pancreatitis.

Imaging

Although the presence of enhancing nodules and septations correlates with malignancy, absence of these findings does not preclude malignancy. On imaging, mucinous cystadenocarcinomas (Figure 12-6) are seen as large, complex, cystic pancreatic masses that can be distinguished from mucinous cystadenomas by the presence of intracystic enhancing soft tissue. These tumors are usually large (>6 cm), and malignancy is usually not seen in tumors smaller than 4 cm unless intramural nodules are present.20 Hence, any enhancing soft tissue within a cystic neoplasm depicted on CECT or MRI is considered an indication for resection; however, all mucinous lesions are considered premalignant and are generally resected because, radiologically in the majority of cases, discrimination between benign and malignant MCN is currently impossible. We have usually seen that, when the adjacent vessel such as the splenic vein is occluded, this finding may suggest a trend toward malignancy. Staging is similar to that of pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Treatment

Surgical resection is recommended for all patients with suspected MCN who are suitable operative candidates. Whereas surgical resection of patients with noninvasive disease is usually curative, invasive MCN is characterized by frequent recurrence and consequently poorer survival; preoperative or postoperative chemoradiation may be useful in these patients.26,27 Gemcitabine appears to be effective in the case of pancreatic cystadenocarcinomas with peritoneal metastases.28,29 This treatment strategy is commonly offered to patients with resectable pancreatic cancer in order to achieve margin-negative resection and to restrict aggressive surgical therapy for those patients whose cancers have a favorable biology (or those cancers that do not progress during the preoperative chemotherapy phase).30

Surveillance

Key Points Mucinous cystic neoplasms

• Mucinous cystadenomas and carcinomas have ovarian stroma.

• They are unilocular and may have papillary projections.

• They commonly do not communicate with the main pancreatic duct.

• They are exclusively seen in menstruating females.

• On EUS-FNA, the CEA can be high as 200 to 500 and the amylase is low.

VI Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Tumors

Introduction

The three main types of IPMTs are classified based on their location: that is, the main duct type, the side branch duct type (BDIPMT), and the combined type.31 These tumors produce mucin, which accumulates in the ducts and results in cystic dilatation of the duct. Most commonly, IPMTs involve the main pancreatic duct, but they may also affect the side branches.32 Depending on their size and type, they can be premalignant or frankly malignant. They may exhibit a spectrum of dysplasia ranging from minimal mucinous hyperplasia to invasive carcinoma.33 The differential diagnosis of BDIPMTs may include a pseudocyst.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

IPMTs were first described by Ohashi and colleagues in 1982, and the term was conceived by Sessa and associates in 1994.32 These tumors arise from the columnar epithelium of the pancreatic duct. The cells become dysplastic and form papillary projections that extend into the pancreatic ducts and secrete mucin. These tumors are more commonly seen in males, with a male-to-female ratio of 2:1. These patients typically present in the seventh to eighth decades of life. Initially, IPMNs were thought to represent only 5% of all cystic lesions, but they are being reported increasingly in numbers, likely owing to increased awareness of the disease and the use of cross-sectional imaging modalities. The older term for IPMN was “duct ectatic mucinous tumor.” This is a mucin-producing tumor that arises from the pancreatic ductal epithelium. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), IPMN is classified based on the degree of epithelial dysplasia: adenoma, borderline tumor, and carcinoma (either in situ or invasive).34

Anatomy and Pathology

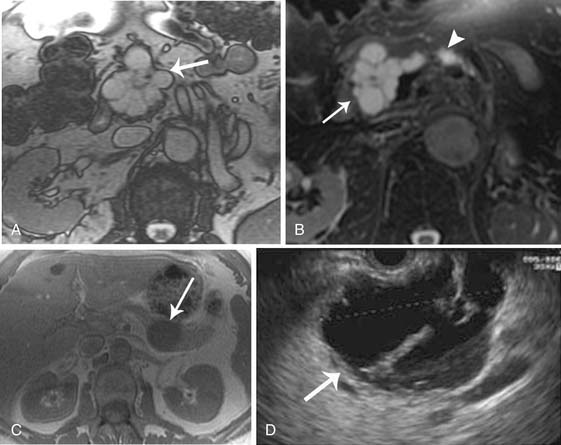

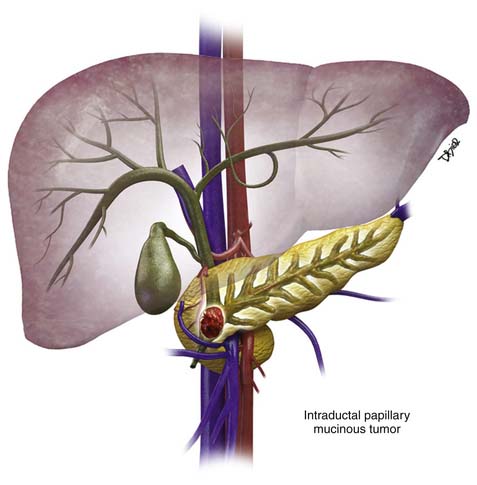

IPMNs may be classified depending on disease process whether it involves the main pancreatic duct (Figure 12-7) or isolated side branches. They may be also characterized depending on whether they produce a diffuse pattern of ductal dilatation or a segmental cystic appearance.35 The location of the tumor is an important factor for the prognosis.36 Twenty percent to 30% are multifocal and 5% to 10% involve the entire pancreas.22,37

Main Duct–Type Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm

Anatomy and Pathology

These are different from the mucinous cystic tumors because they lack an associated ovarian-type stroma. There are two types of main duct IPMN histologically: the intestinal or gastric and the pancreaticobiliary type.25,31 The intestinal subtype produces abundant extracellular mucin as it progresses toward invasive malignancy and displays the typical good survival after surgical resection, which is normally associated with IPMTs.25 The pancreaticobiliary subtypes evolve into ductal adenocarcinoma and have the associated poor survival that characterizes invasive ductal adenocarcinoma of pancreatic origin.25 Predictors of malignancy are main duct type with mucin leakage from the ampulla of Vater, main pancreatic duct dilatation, tumor size, jaundice, and diabetes.38–40 The pancreaticobiliary type of IPMN has a higher malignant potential than the intestinal or gastric type.31 Mucin extruding from the ampulla of Vater is a pathognomonic feature of a main duct IPMN, seen on cholangiopancreatography, and is caused by excessive mucin production by the neoplastic cells.13,21 The tumors have a papillary or polypoid appearance and arise from mucinous cells, which are transformed pancreatic ductal epithelium.35,41 When the size of the main duct increase to 1 cm, the tumor nodule may show cell atypia, ranging from slight dysplasia to frank invasive carcinoma. In addition, these cell types may coexist within the same lesion. The spectrum of IPMNs range from noninvasive neoplasms, with varying degrees of epithelial dysplasia, to foci of carcinoma in situ and frank invasive adenocarcinoma. The precise rate of progression from benign to malignant status is unknown but is estimated to range from 5 to 7 years.6,12,38,42 Malignancy is more common in the main duct IPMNs and approximately 60% to 92% of cases demonstrate invasive carcinoma.41,43 The prevalence of invasive carcinoma is higher in main duct IPMN (23-57%).4,34

Clinical Presentation

These tumors occur most frequently in men, with a mean age of 65 years.22 Most patients with main duct IPMNs are symptomatic and present with epigastric abdominal pain, which is frequently exacerbated by food. The pain is likely due to the fact that mucin production blocks the pancreatic duct and can result in pancreatitis, leading to ductal strictures. Patients frequently complain of pain, often epigastric in nature, that radiates to the back.6 Therefore, many patients may be misdiagnosed as having chronic pancreatitis, rather than IPMNs; other symptoms and signs include weight loss, fever, and jaundice.42

Patterns of Tumor Spread

Patients with invasive carcinoma can develop metastases to the liver or lung or can have local recurrence.44

Imaging

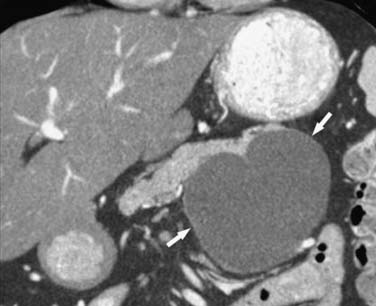

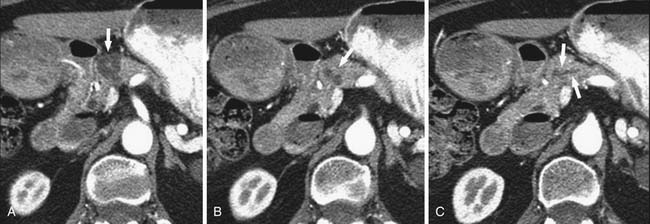

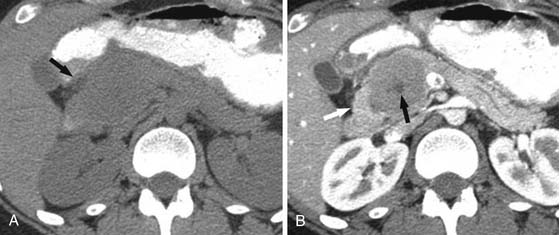

Several imaging modalities can be used to image IPMNs, such as CT, MR, MRCP, EUS, and PET/CT. Any one of these or combinations of the modalities have the ability to characterize these lesions. MRI may provide better depiction of ductal communication than CT.45,46 The appearance of IPMNs on CT depends on their type and location. The main pancreatic duct is dilated in the setting of a main duct IPMN (Figures 12-8 and 12-9); sometimes the entire duct can be dilated if the tumor is present in the head, and there may be segmental dilatation of the duct if the tumor is present in the body. However, eventually, the entire duct becomes dilated as the disease progresses.21,22

Because these tumors result in pancreatitis, changes in the pancreatic parenchyma may be visible on CT and MRI, such as loss of T1 signal on the noncontrast images and delayed uptake of contrast material, which are indicative of chronic fibrosis.47 On CT, US, and MRI, the main duct may be markedly dilated and tortuous. In some cases, mural nodules can be identified that show enhancement after administration of intravenous contrast. The gland may become atrophic and dysmorphic calcifications may be present, mimicking findings of chronic pancreatitis. However, patients with main duct IPMN present at a later age than those with chronic pancreatitis and may have a bulging papilla on imaging due to mucin production. The features of malignancy or invasive carcinoma on imaging in main duct IPMN include main duct dilatation greater than 1.5 cm in diameter, enhancing nodules or excrescences, diffuse or multifocal involvement of the pancreatic duct, presence of a focal hypovascular soft tissue mass, or bile duct obstruction.48 All main duct lesions are considered premalignant and should be considered for surgical resection.4,15

Branch Duct Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms

Anatomy and Pathology

Branch-type IPMNs follow a more clinically indolent course than “duct-type” or “combined-type.” These tumors are located in the head of the pancreas gland (usually the uncinate process). Histologically, the branch-type IPMNs display a distinct architecture, known as gastric foveolar, which rarely progresses toward frank malignancy.25 The prevalence of cancer in branch duct IPMN ranges from 6% to 46%.4,34,44 They usually occur in the uncinate process of the pancreas and appear as a small cystic mass described on imaging as a “bunch of grapes.” On US, they are well-defined hypoechoic cystic lesions with internal septations. This tumor secretes a large amount of mucin, which may extrude into the main pancreatic duct and cause main pancreatic ductal dilatation downstream from the site of communication of the side branch to the main pancreatic duct. Usually, in the setting of malignancy, the side branch communication is larger than that of the benign lesion. BDIPMTs can be multifocal because all pancreatic ductal epithelium may be at risk for developing malignancy. 44

Clinical Presentation

These are found in younger patients and have a low potential for malignancy.49

Imaging

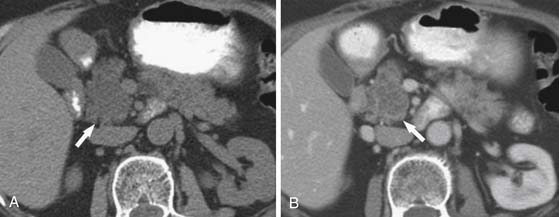

On cross-sectional imaging, IPMNs are characterized by cystic dilatation of the ductal side branches. Sometimes, papillary projections or intramural nodules can be seen with the dilated side branch at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), MRCP, or CECT. The previously mentioned imaging modalities can also show communication of the dilated side branch to the main pancreatic duct, which confirms the diagnosis. On MRI, BDIPMTs show dilatation of multiple side branches on T2WIs, and these lesions are most commonly seen in the pancreatic head.50 These tumors may mimic a SCA; however, BDIPMTs (Figure 12-10) show communication with the main pancreatic duct, which helps differentiate between these two entities. The imaging features suggestive of malignancy include enhancing soft tissue nodularity and a size greater than 3.0 cm.37,44,51–53 In the absence of these features, some groups have advocated conservative management with regular follow-up imaging evaluations of localized BDIPMTs in asymptomatic patients.37

Combined Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms

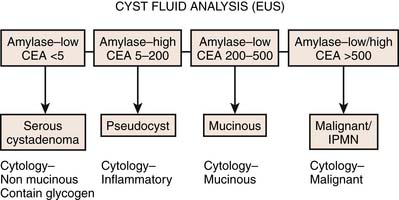

The aspirated fluid is sent for cytology (Figure 12-11), cyst fluid tumor markers, and amylase. Cyst fluid viscosity has been described as higher in mucinous cysts.54 Fluid viscosity is assessed at the aspiration by measuring “string sign.” The string sign is determined by placing a drop of fluid on a surface of a glass slide and measuring the maximum length of stretch before disruption of the mucous string. This is often used as a surrogate marker of cyst fluid viscosity because the viscosity is not directly measured. Perhaps in the near future, we will see an emergence of a device that can immediately give accurate measurements of the string sign. The use of cyst fluid tumor markers such as CEA, CA19-9, CA72-4, CA125, and CA15-3 has been proposed but also has limitations.54–57

Figure 12-11 Analysis of the cystic fluid in different cystic lesions after endoscopic ultrasound–guided aspiration.

In a study by Brugge and colleagues,58 CEA was found to be the most specific tumor marker for malignancy in pancreatic cysts. Using the CEA value of 192 ng/mL, the sensitivity for diagnosis of a mucinous cyst was 75%, with a specificity of 84%, and an accuracy of 79%. In comparison, the accuracy of EUS morphology was 51% and cytology was 59%.58 For cytologic examination, once the specimens are obtained, approximately half of the smears are air-dried and stained with Diff-Quik (Mercedes Medical, Sarasota, FL), and the remaining smears are fixed in 95% alcohol for Papanicolaou staining. Diagnostic specimens are analyzed for the presence of mucinous epithelium, extent of cytologic atypia, and presence of malignant cells. At most large-volume centers, the immediate staining and review by an experienced cytologist are available before the EUS session is terminated. The availability of an on-site cytologist clearly reduces the number of FNA passes to establish the final diagnosis, thus diminishing procedure time and complications.

Treatment

Although cross-sectional imaging can be used to diagnose IPMN with reasonable accuracy, no combination of imaging techniques, serum tumor markers, and tumor biopsies can reliably distinguish invasive from noninvasive disease. Because of the high rates of invasive disease associated with main duct lesions, we agree with the recently published international consensus guidelines for the management of patients with MCN and IPMN, which suggest that resection be considered for all patients with main duct IPMN of good functional status and a reasonable life expectancy.4 Surgical resection should also be recommended in patients with symptomatic or large (>3 cm) branch duct lesions. In contrast, a period of observation is reasonable for asymptomatic patients with branch duct IPMN less than 3 cm in diameter and no radiographic features suggestive of malignancy. These patients have been shown to have a favorable survival despite nonoperative management.51,59,60 In this group, close follow-up with cross-sectional imaging should be used to detect an increase in tumor size, change in radiographic characteristics, or the development of symptoms, any of which would suggest the need to reevaluate the role of surgical resection. Importantly, small branch duct IPMNs in patients of advanced age do not need immediate surgery.

Adjuvant chemoradiation is offered for patients with invasive adenocarcinoma, and this improves survival as indicated by several prospective studies.61,62 At M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, preoperative therapy is commonly offered to patients with resectable pancreatic cancer, with intent to (1) achieve margin-negative resection and (2) restrict aggressive surgical therapy for those patients whose cancers have a favorable biology (or those cancers that do not progress during the preoperative chemotherapy phase).30 Such a strategy can also apply for cystic pancreatic tumors that have an invasive component because these can grow to significant dimensions before detection and the likelihood of margin-negative resection can be improved with the preoperative approach. Gemcitabine, either as a single agent or in combination with erlotinib, is considered as the standard of care for the treatment of advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma; however, the resultant clinical benefit is modest.63,64

Adjuvant chemoradiation can improve the median survival in patients with IPMN with an invasive component.65 Adjuvant chemoradiation in patients with IPMN with an invasive component is associated with a significantly higher overall survival rate among node-positive patients and those with positive margins. Anatomic partial pancreatectomy represents the standard surgical treatment for patients with IPMN. Surgical margins should be assessed intraoperatively by frozen section analysis.

Surveillance

Patients with residual noninvasive IPMN at the pancreatic transection margin have a very low likelihood of developing recurrent disease.66 We elect to follow these patients annually after the initial postoperative period with repeat imaging of the pancreatic remnant. In contrast, we believe that an attempt should be made to achieve margins clear of invasive IPMN in patients with good performance status. Postoperative survival of patients with IPMN is related primarily to the presence of invasive adenocarcinoma. In rare instances, this may require total pancreatectomy. The high rates of recurrence after resection for invasive disease mandate closer follow-up; we follow these patients as we would patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and use cross-sectional imaging at each visit to detect evidence of locoregional or distant recurrence.

Key Points Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms

• A cystic lesion that communicates with the main pancreatic duct is a branch duct IPMN.

• When the main pancreatic duct is dilated to greater than 15 mm, it is suggestive of a main duct IPMN.

• Presence of nodules in the main duct IPMN or branch duct IPMN is suggestive of malignancy.

• Tumor in the IPMN can transform into invasive carcinoma, making it difficult to differentiate from ductal adenocarcinoma.

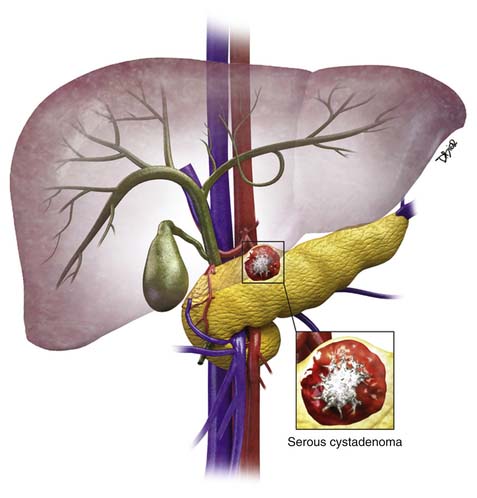

VII Serous Cystadenoma

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

SCAs more commonly occur in women than in men; in women they occur in the sixth decade of life and in men in the seventh decade.22,67 These cystic lesions present with nonspecific symptoms such as epigastric abdominal pain and weight loss. They are categorized into microcystic SCAs (multilocular) and oligocystic lesions (unilocular). Sometimes, the unilocular/macrocystic SCA/oligocystic serous cyst adenoma (OCA) may have a single locule, and in an appropriate clinical setting, it would be difficult to distinguish this from an MCN6 or even a pseudocyst.

These tumors do not produce mucin, have a lobulated well-defined border, and have a histologically clear or eosinophil-rich cytoplasm. SCAs are usually less than 5 cm in diameter, with a median size of 25 to 30 mm. These tumors can be seen in VHL syndrome,21,68 which consists of retinal and central nervous system hemangioblastomas and pheochromocytomas. The VHL gene is also seen in sporadic cases of SCA. These tumors are benign and the risk of malignancy is low at approximately 3%.69

Microcystic Serous Cystadenomas

Anatomy and Pathology

The microcystic SCAs (glycogen-rich adenomas) are composed of several locules, usually more than six in number, with the size of the locules ranging from 0.1 to 2.0 cm, but typically less than 1 cm, resembling a sponge, and may have a calcified stellate scar,2,21 which is seen only in approximately 10% to 30% of the cases. The growth rate of these tumors depends on their size, tumors smaller than 4 cm grow at a rate of 1.2 cm/yr, whereas tumors greater than 4 cm grow 1.98 cm/yr.70,71

Clinical Presentation

Most tumors are found incidentally, but large tumors can cause symptoms owing to mass effect. For example, a mass in the pancreatic head can cause jaundice by obstructing the common bile duct.68

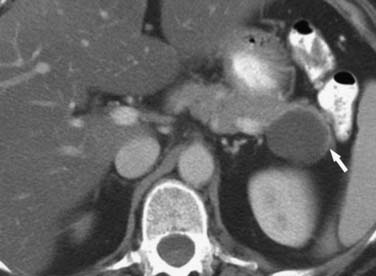

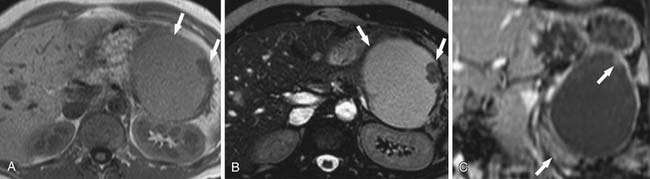

Imaging

On cross-sectional imaging, these are purely cystic masses and have a “honeycomb” appearance. On the noncontrast examination, they have CT attenuation of less than 20 HU (Figure 12-12); they do enhance due to the central fibrovascular scar.2,21 Enhancement in this lesion may be misleading in some cases in which the tiny locules are not visible; this cystic neoplasm may be misdiagnosed for a solid mass such as a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor.

In these situations, MRI (Figure 12-13) is the most appropriate modality to definitively characterize these tumors because they have a characteristic high T2 signal due to presence of fluid and the thin fibrous septa between them, enhance on the delayed phase of contrast. On US, these tumors can appear as echogenic masses or a partly solid mass with cystic and anechoic areas. On color Doppler, the peripheral areas and the central areas show flow. These tumors do not communicate with the main pancreatic duct as do the BDIPMNs.72 If chunky calcification is present in the central scar, a corresponding signal void may be seen on MRI on any sequence and posterior acoustic shadowing may be seen on US. The echo features of SCA on EUS include sunburst calcification with numerous microcysts; when such an appearance is seen, this is pathognomonic of a SCA.

Oligocystic Serous Cystadenoma

Anatomy and Pathology

These tumors are larger, have fewer locules, and may mimic a mucinous cystadenoma on imaging.70 The individual cysts may be larger than 2 cm, and rarely, only one locule may be seen.

Imaging

The imaging features of this tumor overlap with that of a mucinous cystadenoma (Figure 12-14). When a unilocular lesion is seen in the head of the pancreas containing no papillary projections or intramural nodularity, one should consider a diagnosis of an OCA.14 On sonographic evaluation, these tumors may appear as solid echogenic masses due to the many interfaces produced by the numerous cysts or may be completely anechoic and cystic, if they are made of a single locule.

Surveillance

Patients with incidentally discovered, slow-growing tumors less than 4 cm in diameter may be observed initially with semiannual/annual cross-sectional imaging to evaluate the presence or absence of tumor growth. It is reasonable to consider surgical resection for incidentally discovered tumors greater than 4 cm (although this number is clearly somewhat arbitrary) or those that exhibit rapid growth or a significant change in radiographic appearance during observation, particularly in younger patients. Resection is also recommended in the increasingly uncommon case in which a definitive diagnosis cannot be established. However, these are general guidelines and each case is different. In general, it is our bias that surgery is applied too early and too often for patients with this disease, particularly for those of advanced age with asymptomatic tumors less than 4 to 5 cm in size. For patients selected for surgical therapy, complete anatomic resection by pancreaticoduodenectomy or distal pancreatectomy is generally curative. The reported 5-year survival73,74 is high at greater than 81%. Therefore, postoperative surveillance is probably unnecessary; we follow these patients after the initial postoperative period only to screen for the presence of gastrointestinal or metabolic complications after pancreatectomy.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

These tumors are less common than IPMNs, SCAs, and MCNs. The histogenesis of these tumors are unknown; however, ultrastructural and immunohistochemical studies have suggested that they have both epithelial and neuroendocrine differentiation.75

Anatomy and Pathology

On pathology, necrotic debris, blood, and foamy macrophages can be seen in these cystic areas.14,21 These tumors are usually large at presentation (>10 cm), can occur anywhere within the pancreas, and can have calcification.76 SPTs are usually seen in young women in the second to third decades of life with an age range of 7 to 79 years but are reported in childhood.77,78 The tumors can have both epithelial and neuroendocrine components. The tumors occur exclusively in the pancreas. SPTs are tumors of low malignant potential. These tumors are predominantly solid, develop cystic spaces when they degenerate, and vary in both size and morphology.79

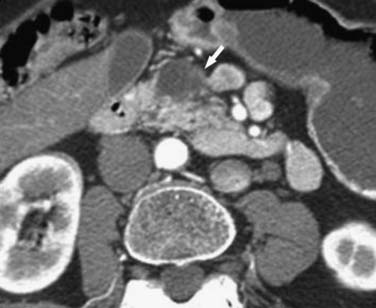

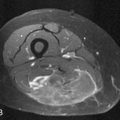

Imaging

On CT (Figures 12-15 and 12-16), they appear as solid masses that enhance avidly on the arterial phase and plateau on the portal venous and delayed phases of contrast. They may have a central scar, may have eccentric calcifications, and may show hemorrhage. On T2WI, these tumors are well-circumscribed and have slightly higher signal intensity. Tumors that are predominantly cystic will have a high T2 signal intensity similar to that of fluid. These tumors enhance progressively, which can help differentiate them from neuroendocrine neoplasm, which commonly have arterial phase enhancement. On noncontrast T1WIs, hemorrhage within the tumor has high signal intensity. On US, they may show fluid debris levels and posterior acoustic enhancement. Benign SPTs are smoothly lobulated and encapsulated; sometimes, they can be completely cystic and contain rim calcifications.76 The features of malignancy include discontinuity of the capsule or eccentric lobulated margin, focal nodular calcification, and amorphous/scattered calcification; upstream main pancreatic duct dilatation may be present.76 Peritoneal, cutaneous, and hepatic metastases have all been reported after excision of SPT; however, nodal metastases appear to be rare.79

Treatment

Surgery is offered in these patients to prevent local tumor growth and distant metastases and palliate symptoms. Although locoregional tumor extension and metastasis may be identified in up to 20% of patients, surgical resection can lead to favorable survival even in the face of advanced disease. Pancreaticoduodenectomy or distal pancreatectomy is usually required to achieve a complete en bloc resection owing to the large size of these tumors. Enucleation and central pancreatectomy may be possible in some cases because lymph node metastases are rare, making formal lymphadenectomy relatively unimportant.80 Overall, aggressive surgical resection is associated with a 5-year survival exceeding 95%.81

Surveillance

Guidelines for Imaging Surveillance

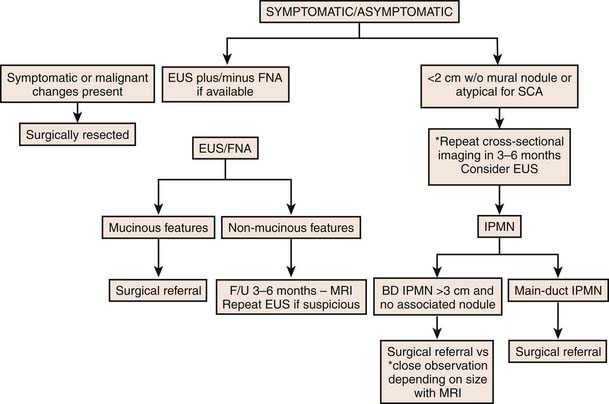

The natural history of cystic pancreatic lesions is still under investigation and selective observations are emerging.4,15,82,83 The mortality rate from surgery in patients with resected cysts is approximately 2.9%.84 Thus, it is appropriate to follow asymptomatic pancreatic cysts if they are smaller than 3 cm. Although the endosonographic appearance of the cyst may be helpful in differentiating between pancreatic cysts, there are many limitations; the specificity is inadequate to use EUS as a sole diagnostic modality.57 Furthermore, the interobserver agreement among experienced endosonographers is inconsistent in distinguishing between neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions.85

The management of MCNs (Figure 12-17) offers a challenge to clinicians. When considering the therapeutic options for patients with a mucinous cyst, the risk/benefit ratio should be carefully assessed. Recently, ethanol ablation of pancreatic cysts has been evaluated in a prospective, multicenter, randomized trial. EUS-guided ethanol lavage resulted in a greater decrease in pancreatic cyst size compared with saline solution lavage with a similar safety profile. Overall CT-defined complete pancreatic cyst ablation was reported as 33.3% (12 of 36 cysts).86

Finally, the role of conservative management with serial abdominal imaging and surgical intervention only if there are worrisome changes suggestive of malignant transformation has not been fully elucidated. A study suggested that many asymptomatic pancreatic cystic neoplasms could be managed without surgical resection over a mean of 4 years.87 However, those patients with mucinous cysts who do not undergo surgical resection should be closely followed with serial abdominal imaging for any changes suggestive of malignant transformation.

Cysts that are 3 cm or greater should be followed if indeterminate because, even without the presence of a solid component, pancreatic cysts can be malignant in 3% of the cases.82,88–90 Follow-up in pancreatic cystic lesions is necessary because the probability of malignancy is higher in enlarging cysts and also increases with age older than 70 years,91,92 and up to 20% of cysts may require future surgery for enlargement or the development of symptoms.84 Because cystic pancreatic lesions are indolent and slow-growing, timely excision offers a good chance of cure. Because SCAs grow slowly,71 tumors smaller than 4 cm in an asymptomatic patient can be safely followed at an interval of a year for 2 years unless the patient becomes symptomatic.

For lesions that are potentially malignant or premalignant (i.e., mucinous in origin) or that are indeterminate, a more conservative approach is necessary.4 Because asymptomatic cystic lesions less than 3 cm in size, without main duct dilatation (≤6 mm), or mural nodules have a low risk of malignancy, a yearly follow-up is recommended if the lesion is less than 10 mm, 6- to 12-month follow-up for lesions between 10 and 20 mm, and every 6-month follow-up for lesions larger than 2 cm.4 If the duct is dilated greater than 6 mm, there is an increased size of the lesion greater than 30 mm, or intramural nodules are seen, surgical resection is indicated if the patient is a good candidate with reasonable life expectancy.4,15,90 The patient’s age should be considered when deciding which modality is to be used to follow-up these cystic lesions because the organ dose of radiation in patients younger than 40 years is much greater than in those older than 40 years.93 There are no clear guidelines to suggest the length of follow-up in the setting of indeterminate cysts.

The international guidelines developed during the Eleventh Congress of the International Association of Pancreatology held in Sendai, Japan, from July 11 through 14, 2004, suggests follow-up of resected benign branch duct IPMNs for several years because these tumors have a malignant potential.4 Follow-up of resected benign IPMNs with either CECT or MRI is recommended yearly for the first 5 years after surgery, and then obtaining an imaging evaluation only if abdominal symptoms present; similarly, patients with invasive carcinoma should have follow-up imaging every 6 months for the first 2 years, and yearly thereafter.44 Patients with resected invasive IPMNs and malignant MCNs are followed every 4 months for a period of 2 years and then every 6 months after that.

Key Points Follow-up

• Cysts that are 3 cm or greater should be followed if indeterminate.

• An SCA growth measuring less than 4 cm in an asymptomatic patient can be safely followed at an interval of year for 2 years.

• Asymptomatic cystic lesions less than 3 cm in size, without main duct dilatation (≤6 mm), or mural nodules. Yearly follow-up is recommended if the lesion is less than 10 mm, 6- to 12-month follow-up for lesions between 10 and 20 mm, and every 6-month follow-up for lesions larger than 20 mm.

• Follow-up of resected benign IPMNs with either CECT or MRI is recommended yearly for the first 5 years after surgery.

• Similarly, patients with invasive carcinoma after resected IPMN should have follow-up imaging every 6 months for the first 2 years, and yearly thereafter.

Summary

When a cystic mass (see Table 12-1) is seen in the body or tail of the pancreas in a menstruating female, one can suggest an MCN; in these cases, resection is warranted because these lesions have a potential for malignancy. A cystic lesion having a honeycomb appearance in a postmenopausal female likely represents an SCA and can be safely followed if it is less than 4 cm and asymptomatic. A solid mass within the pancreas in a young female containing cystic and solid components may represent an SPT.

In conclusion, radiologists should take into account the patient’s presentation, the age, and the gender while interpreting cross-sectional images, which can help guide appropriate diagnosis and treatment plan of a cystic lesion of the pancreas.

1. Warshaw A.L., Rutledge P.L. Cystic tumors mistaken for pancreatic pseudocysts. Ann Surg. 1987;205:393-398.

2. Sahani D.V., Kadavigere R., Saokar A., et al. Cystic pancreatic lesions: a simple imaging-based classification system for guiding management. Radiographics. 2005;25:1471-1484.

3. Sperti C., Pasquali C., Decet G., et al. F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in differentiating malignant from benign pancreatic cysts: a prospective study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:22-28. discussion 28–29

4. Tanaka M., Chari S., Adsay V., et al. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2006;6:17-32.

5. Safioleas M.C., Moulakakis K.G., Manti C., et al. Clinical considerations of primary hydatid disease of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2005;5:457-461.

6. Salvia R., Festa L., Butturini G., et al. Pancreatic cystic tumors. Minerva Chir. 2004;59:185-207.

7. Singhal D., Kakodkar R., Sud R., et al. Issues in management of pancreatic pseudocysts. JOP. 2006;7:502-507.

8. Baron T.H., Morgan D.E. The diagnosis and management of fluid collections associated with pancreatitis. Am J Med. 1997;102:555-563.

9. Tanaka A., Takeda R., Utsunomiya H., et al. Severe complications of mediastinal pancreatic pseudocyst: report of esophagobronchial fistula and hemothorax. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2000;7:86-91.

10. Boulanger S., Volpe C.M., Ullah A., et al. Pancreatic pseudocyst with biliary fistula: treatment with endoscopic internal drainage. South Med J. 2001;94:347-349.

11. Tanaka T., Matsugu Y., Nakahara H., et al. A case of mediastinal pancreatic pseudocyst with pancreatic pleural effusion in which internal fistula was diagnosed by magnetic resonance image [in Japanese]. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2008;105:81-85.

12. Flati G., Salvatori F., Porowska B., et al. Severe hemorrhagic complications in pancreatitis. Ann Ital Chir. 1995;66:233-237.

13. Grace P.A., Williamson R.C. Modern management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Br J Surg. 1993;80:573-581.

14. Kim Y.H., Saini S., Sahani D., et al. Imaging diagnosis of cystic pancreatic lesions: pseudocyst versus nonpseudocyst. Radiographics. 2005;25:671-685.

15. Katz D.S., Friedel D.M., Kho D., et al. Relative accuracy of CT and MRI for characterization of cystic pancreatic masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:657-661.

16. Leung R.S., Biswas S.V., Duncan M., et al. Imaging features of von Hippel–Lindau disease. Radiographics. 2008;28:65-79. quiz 323

17. Kosmahl M., Egawa N., Schroder S., et al. Mucinous nonneoplastic cyst of the pancreas: a novel nonneoplastic cystic change? Mod Pathol. 2002;15:154-158.

18. Hruban R.H., Pitman M.B., Klimstra D.S. Non-neoplastic tumor and tumor-like lesions. In: Silverberg S.G., Sobin L.H. Atlas of Tumor Pathology: Tumors of the Pancreas. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2007:358-360.

19. Goh B.K., Tan Y.M., Chung Y.F., et al. A review of mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas defined by ovarian-type stroma: clinicopathological features of 344 patients. World J Surg. 2006;30:2236-2245.

20. Crippa S., Salvia R., Warshaw A.L., et al. Mucinous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas is not an aggressive entity: lessons from 163 resected patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:571-579.

21. Adsay N.V. Cystic neoplasia of the pancreas: pathology and biology. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:401-404.

22. Campbell F., Azadeh B. Cystic neoplasms of the exocrine pancreas. Histopathology. 2008;52:539-551.

23. Goh B.K., Tan Y.M., Yap W.M., et al. Pancreatic serous oligocystic adenomas: clinicopathologic features and a comparison with serous microcystic adenomas and mucinous cystic neoplasms. World J Surg. 2006;30:1553-1559.

24. Nishihara K., Kawabata A., Ueno T., et al. The differential diagnosis of pancreatic cysts by MR imaging. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:714-720.

25. Singh M., Maitra A. Precursor lesions of pancreatic cancer: molecular pathology and clinical implications. Pancreatology. 2007;7:9-19.

26. Doberstein C., Kirchner R., Gordon L., et al. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Mt Sinai J Med. 1990;57:102-105.

27. Wood D., Silberman A.W., Heifetz L., et al. Cystadenocarcinoma of the pancreas: neo-adjuvant therapy and CEA monitoring. J Surg Oncol. 1990;43:56-60.

28. Mizuta Y., Akazawa Y., Shiozawa K., et al. Pseudomyxoma peritonei accompanied by intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2005;5:470-474.

29. Shimada K., Iwase K., Aono T., et al. A case of advanced mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of the pancreas with peritoneal dissemination responding to gemcitabine. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 36, 2009. 995–998

30. Evans D.B., Varadhachary G.R., Crane C.H., et al. Preoperative gemcitabine-based chemoradiation for patients with resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3496-3502.

31. Takasu N., Kimura W., Moriya T., et al. Intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms of the gastric and intestinal types may have less malignant potential than the pancreatobiliary type. Pancreas. 2010;39:604-610.

32. Sessa F., Solcia E., Capella C., et al. Intraductal papillary-mucinous tumours represent a distinct group of pancreatic neoplasms: an investigation of tumour cell differentiation and K-ras, p53 and c-erbB-2 abnormalities in 26 patients. Virchows Arch. 1994;425:357-367.

33. D’Angelica M., Brennan M.F., Suriawinata A.A., et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an analysis of clinicopathologic features and outcome. Ann Surg. 2004;239:400-408.

34. Pelaez-Luna M., Chari S.T., Smyrk T.C., et al. Do consensus indications for resection in branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm predict malignancy? A study of 147 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1759-1764.

35. Lack E. Pathology of the Pancreas, Gallbladder, Extrahepatic Biliary Tract and Ampullary Region. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003.

36. Terris B., Ponsot P., Paye F., et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas confined to secondary ducts show less aggressive pathologic features as compared with those involving the main pancreatic duct. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1372-1377.

37. Salvia R., Crippa S., Falconi M., et al. Branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: to operate or not to operate? Gut. 2007;56:1086-1090.

38. Shima Y., Mori M., Takakura N., et al. Diagnosis and management of cystic pancreatic tumours with mucin production. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1041-1047.

39. Yamaguchi K., Ogawa Y., Chijiiwa K., et al. Mucin-hypersecreting tumors of the pancreas: assessing the grade of malignancy preoperatively. Am J Surg. 1996;171:427-431.

40. Traverso L.W., Peralta E.A., Ryan J.A.Jr., et al. Intraductal neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Surg. 1998;175:426-432.

41. Balzano G., Zerbi A., Di Carlo V. Intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas: incidence, clinical findings and natural history. JOP. 2005;6:108-111.

42. Sohn T.A., Yeo C.J., Cameron J.L., et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an updated experience. Ann Surg. 2004;239:788-797. discussion 797–799

43. Salvia R., Fernandez-del Castillo C., Bassi C., et al. Main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: clinical predictors of malignancy and long-term survival following resection. Ann Surg. 2004;239:678-685. discussion 685–687

44. Rodriguez J.R., Salvia R., Crippa S., et al. Branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: observations in 145 patients who underwent resection. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:72-79. quiz 309–310

45. Song S.J., Lee J.M., Kim Y.J., et al. Differentiation of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms from other pancreatic cystic masses: comparison of multirow-detector CT and MR imaging using ROC analysis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26:86-93.

46. Waters J.A., Schmidt C.M., Pinchot J.W., et al. CT vs MRCP: optimal classification of IPMN type and extent. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:101-109.

47. Zhang X.M., Shi H., Parker L., et al. Suspected early or mild chronic pancreatitis: enhancement patterns on gadolinium chelate dynamic MRI. Magnetic resonance imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;17:86-94.

48. Manfredi R., Graziani R., Motton M., et al. Main pancreatic duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: accuracy of MR imaging in differentiation between benign and malignant tumors compared with histopathologic analysis. Radiology. 2009;253:106-115.

49. Tanaka M. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: diagnosis and treatment. Pancreas. 2004;28:282-288.

50. Procacci C., Megibow A.J., Carbognin G., et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous tumor of the pancreas: a pictorial essay. Radiographics. 1999;19:1447-1463.

51. Matsumoto T., Aramaki M., Yada K., et al. Optimal management of the branch duct type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:261-265.

52. Sugiyama M., Abe N., Yamaguchi Y., et al. Endoscopic pancreatic stent insertion for treatment of pseudocyst after distal pancreatectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:538-539.

53. Irie H., Honda H., Aibe H., et al. MR cholangiopancreatographic differentiation of benign and malignant intraductal mucin-producing tumors of the pancreas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:1403-1408.

54. Lewandrowski K.B., Southern J.F., Pins M.R., et al. Cyst fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cysts. A comparison of pseudocysts, serous cystadenomas, mucinous cystic neoplasms, and mucinous cystadenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1993;217:41-47.

55. Ryu J.K., Woo S.M., Hwang J.H., et al. Cyst fluid analysis for the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cysts. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;31:100-105.

56. van der Waaij L.A., van Dullemen H.M., Porte R.J. Cyst fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions: a pooled analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:383-389.

57. Song M.H., Lee S.K., Kim M.H., et al. EUS in the evaluation of pancreatic cystic lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:891-896.

58. Brugge W.R., Lewandrowski K., Lee-Lewandrowski E., et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1330-1336.

59. Serikawa M., Sasaki T., Fujimoto Y., et al. Management of intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: treatment strategy based on morphologic classification. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:856-862.

60. Sugiyama M., Izumisato Y., Abe N., et al. Predictive factors for malignancy in intraductal papillary-mucinous tumours of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1244-1249.

61. Chu Q.D., Khushalani N., Javle M.M., et al. Should adjuvant therapy remain the standard of care for patients with resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas? Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:539-545.

62. Neoptolemos J.P., Dunn J.A., Stocken D.D., et al. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy in resectable pancreatic cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358:1576-1585.

63. Burris H.A.3rd, Moore M.J., Andersen J., et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403-2413.

64. Moore M.J., Goldstein D., Hamm J., et al. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1960-1966.

65. Swartz M.J., Hsu C.C., Pawlik T.M., et al. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy after pancreatic resection for invasive carcinoma associated with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:839-844.

66. Raut C.P., Cleary K.R., Staerkel G.A., et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: effect of invasion and pancreatic margin status on recurrence and survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:582-594.

67. Wargo J.A., Fernandez-del-Castillo C., Warshaw A.L. Management of pancreatic serous cystadenomas. Adv Surg. 2009;43:23-34.

68. Mohr V.H., Vortmeyer A.O., Zhuang Z., et al. Histopathology and molecular genetics of multiple cysts and microcystic (serous) adenomas of the pancreas in von Hippel–Lindau patients. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1615-1621.

69. Strobel O., Z’Graggen K., Schmitz-Winnenthal F.H., et al. Risk of malignancy in serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Digestion. 2003;68:24-33.

70. Tseng J.F., . Management of serous cystadenoma of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:408-410.

71. Tseng J.F., Warshaw A.L., Sahani D.V., et al. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: tumor growth rates and recommendations for treatment. Ann Surg. 2005;242:413-419. discussion 419–421

72. Martin D.R., Semelka R.C. MR imaging of pancreatic masses. Magn Reson Imaging Clin North Am. 2000;8:787-812.

73. Bassi C., Salvia R., Molinari E., et al. Management of 100 consecutive cases of pancreatic serous cystadenoma: wait for symptoms and see at imaging or vice versa? World J Surg. 2003;27:319-323.

74. Pyke C.M., van Heerden J.A., Colby T.V., et al. The spectrum of serous cystadenoma of the pancreas. Clinical, pathologic, and surgical aspects. Ann Surg. 1992;215:132-139.

75. Adams A.L., Siegal G.P., Jhala N.C. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a review of salient clinical and pathologic features. Adv Anat Pathol. 2008;15:39-45.

76. Chung Y.E., Kim M.J., Choi J.Y., et al. Differentiation of benign and malignant solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33:689-694.

77. Faraj W., Jamali F., Khalifeh M., et al. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas in a 12-year-old female: case report and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2006;16:358-361.

78. Choi S.H., Kim S.M., Oh J.T., et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a multicenter study of 23 pediatric cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1992-1995.

79. Tipton S.G., Smyrk T.C., Sarr M.G., et al. Malignant potential of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 2006;93:733-737.

80. Goh B.K., Tan Y.M., Cheow P.C., et al. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: an updated experience. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:640-644.

81. Papavramidis T., Papavramidis S. Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: review of 718 patients reported in English literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:965-972.

82. Allen P.J., D’Angelica M., Gonen M., et al. A selective approach to the resection of cystic lesions of the pancreas: results from 539 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2006;244:572-582.

83. Walsh R.M., Vogt D.P., Henderson J.M., et al. Natural history of indeterminate pancreatic cysts. Surgery. 2005;138:665-670. discussion 670–671

84. Garcea G., Dennison A.R., Pattenden C.J., et al. Survival following curative resection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. A systematic review of the literature. JOP. 2008;9:99-132.

85. Ahmad N.A., Kochman M.L., Brensinger C., et al. Interobserver agreement among endosonographers for the diagnosis of neoplastic versus non-neoplastic pancreatic cystic lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:59-64.

86. DeWitt J., McGreevy K., Schmidt C.M., et al. EUS-guided ethanol versus saline solution lavage for pancreatic cysts: a randomized, double-blind study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:710-723.

87. Chari S.T., Yadav D., Smyrk T.C., et al. Study of recurrence after surgical resection of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1500-1507.

88. Lahav M., Maor Y., Avidan B., et al. Nonsurgical management of asymptomatic incidental pancreatic cysts. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:813-817.

89. Handrich S.J., Hough D.M., Fletcher J.G., et al. The natural history of the incidentally discovered small simple pancreatic cyst: long-term follow-up and clinical implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:20-23.

90. Sahani D.V., Saokar A., Hahn P.F., et al. Pancreatic cysts 3 cm or smaller: how aggressive should treatment be? Radiology. 2006;238:912-919.

91. Lee S.H., Shin C.M., Park J.K., et al. Outcomes of cystic lesions in the pancreas after extended follow-up. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2653-2659.

92. Spinelli K.S., Fromwiller T.E., Daniel R.A., et al. Cystic pancreatic neoplasms: observe or operate. Ann Surg. 2004;239:651-657. discussion 657–659

93. Brenner D.J., Hall E.J. Computed tomography–an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2277-2284.