41 Cystic Fibrosis

reaching upward toward the sky

With permission from “The Breathing Room: The Art of Living with Cystic Fibrosis” at www.thebreathingroom.org

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a well-known disease to most pediatricians and pediatric palliative care clinicians. Given the degree of familiarity about the disease for the readers of this volume, this chapter intertwines two goals: to provide an updated view of CF in the early twenty-first century and to propose an ideal and somewhat novel model for integrating the pediatric palliative care team into the care of patients and families affected by CF. While the population of adults with CF will soon be larger than that of children,1 this chapter does not include a comprehensive discussion of the palliative care of adults with CF because most are cared for in adult CF centers with different challenges and resources.

As described further in this chapter, the typical patterns of care for patients with CF have historically presented predictable barriers to the successful integration of palliative care. Understanding of the natural history, the changing epidemiology and cultural understanding, and the perceived and actual physical and psychosocial burden of the disease will help palliative care providers better understand how to integrate their clinical expertise and psychosocial support of the patient and family into the established and successful CF model of clinical care. Further, this can be done without disrupting the typically well-established relationships between patients and their families with the CF care team. While the proposed value added model described later and outlined in Table 41-1, may not seem distinctive to many palliative care providers,2 it will be seen as a novel approach by most CF care teams.

TABLE 41-1 Help From Palliative Care Teams

| How can the pediatric palliative care team help the CF team care for children, adolescents and families with CF throughout the lifespan? |

|---|

| Before the diagnosis is made |

| Help the CF care team design and implement a supportive and compassionate approach to those who have a positive newborn screen for CF, realizing that a positive screen can be a distressing experience even if the infant is not diagnosed with the disease. |

| At the time of diagnosis |

|---|

| Help the CF team care develop strategies to mitigate the impact of parental grief following the disclosure of a life-threatening diagnosis in an infant, especially if the infant is apparently healthy. |

| During routine care |

|---|

| Help the CF care team anticipate and prepare for emotional reactions to the first hospitalization, which can trigger parental anxiety about disease progression and mortality. |

| Help the CF care team become comfortable with discussions of mortality throughout the patient’s life, so that the team is prepared for inevitable questions and discussion with patients and families. |

| As the disease progresses |

|---|

| Help the CF care team gain expertise in the assessment and treatment of symptoms throughout the lifespan, including expertise in pain management and assessment of non-pulmonary, non-GI symptoms, such as fatigue or anxiety. |

| Help the CF care team plan a comprehensive roadmap for the decisions, which will be faced by patients, parents, and clinicians in the now rarer instance of a childhood or adolescent death, including anticipatory guidance about the use of aggressive technologies. |

| Offer the CF care team assistance with planning and carrying out the process of transplant decision making. (See Table 41-3.) |

| Offer expertise and experience with managing symptoms and end of life care in different settings, such as at home or through pediatric hospice services, if available. |

| After the death of the child or adolescent |

|---|

| Offer comprehensive bereavement services for the family, siblings, and medical providers. |

An Overview

Cystic fibrosis is a life-threatening genetic disease with an incidence of 1 in 3200 live births in the United States. An estimated 30,000 people are now living with CF in North America.3 CF is a multisystem disease resulting from mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) gene, causing abnormal chloride ion transport across epithelial cells lining the airways, pancreatic ducts, gastrointestinal tract, and reproductive organs. This abnormal transport leads to dehydrated and viscous secretions. Clinical manifestations of this defect include recurrent respiratory infections, nutritional deficiencies related to malabsorption from pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, intestinal obstruction, hepatobiliary disease, diabetes, and male azospermia.4 The natural history of CF is a progressive decline in lung function caused by recurrent infection, inflammation, and bronchial obstruction leading to bronchiectasis and subsequent ongoing inflammation, infection, and airway damage. Chronic inflammation and infection of the airways accounts for most of the morbidity in CF, and the vast majority of patients with CF eventually die from respiratory failure.5

Survival in CF has increased dramatically over time due to advancements in medical care. Additionally, lung transplantation for advanced CF lung disease is an option that may extend life or improve quality of life for select patients. The population of patients with CF is shifting: In 2007, 45% of patients with CF in the United States were adults, and the median predicted survival for patients with CF reached 37.1 years.1 Despite advancements in care and longer survival, patients with CF and their families endure the challenges associated with a chronic disease, including the burden of numerous therapies and disease exacerbations, the knowledge of a limited lifespan, the responsibility of complex decision making regarding lung transplant and other intensive treatments, and the stigma and reproductive choices associated with a genetic disease.

The Current Approach

From the time of diagnosis, daily therapies are prescribed for maintenance of respiratory health and nutritional status, and emphasis is placed on psychosocial implications of chronic disease. To facilitate management of this complex disease, an interdisciplinary approach to care is believed to be essential. In addition to receiving standard medical care from a primary care provider, many patients attend quarterly or more frequent clinic visits and receive hospital care at specialty CF care centers. CF care teams are composed of multiple providers, including physicians, nurses, social workers, dietitians, physical therapists, and respiratory therapists (Table 41-2).

| Provider | Frequency of visits | Role in CF care |

|---|---|---|

| Primary care physician | Variable |

* Other specialty areas may include allergy/immunology, anesthesiology, cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, genetics, genetic counseling, infectious disease, neonatology, obstetrics/gynecology, otolaryngology, psychiatry, psychology, pulmonology, radiology, surgery, and urology.

Adapted from Orenstein DM, Rosenstein BJ, Stern RC. Cystic Fibrosis Medical Care. Lippincott Williams & Williams, Philadelphia, 2000.

For patients with CF, basic respiratory care involves a combination of airway clearance techniques to enhance removal of mucus from the lower airways, aerosolized therapies to facilitate mucus clearance by altering its viscosity, various antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory medications, and exercise.3 Many of these therapies are time-consuming and may prove challenging to maintain. A survey of adults with CF revealed that they spend an average of nearly 2 hours per day on respiratory therapies.6 Children with CF require close supervision from caregivers, and even older patients often need assistance from caregivers to carry out respiratory therapies and other treatments.7 With progressive disease, oxygen may be used with exertion, during sleep, and ultimately constantly.8 Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation may be recommended for patients with hypercarbia and respiratory insufficiency, and has gained favor over time as a bridging therapy for patients awaiting lung transplantation.9

Respiratory exacerbations of CF manifest in many ways, with symptoms including increased cough and sputum production, dyspnea, fatigue, fever, chest pain, hemoptysis, sleep disturbance, and weight loss. Concomitant changes in physiologic measures, including chest exam, oxygen saturation, spirometry measures, and weight, may occur. Treatment of respiratory exacerbations involves additional therapies and hospitalization for severe exacerbations for many patients. Intravenous antibiotics are commonly used, often in combination given the challenges of combating virulent and often drug-resistant CF pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and Burkholderia cepacia, and therapeutic drug monitoring and surveillance for associated toxicities is necessary. Intensification of aerosolized therapies and airway clearance techniques during exacerbations is also common practice.5 Complications of progressive CF lung disease, including pneumothorax, hemoptysis, hypercapnia, pulmonary hypertension, and respiratory failure, prompt more extensive evaluation and treatment, sometimes in the intensive care unit.10

Patients with pancreatic insufficiency must take pancreatic enzyme supplements with food to enhance digestion and reduce the likelihood of intestinal obstruction, as well as taking fat soluble vitamin supplements to prevent vitamin deficiencies. Anti-reflux medications and laxatives are also commonly prescribed. Because of the established correlation between nutritional status and lung function, great emphasis is placed on appropriate growth for children and weight maintenance in adults.11 For many patients who struggle to gain weight, nutritional supplements, appetite stimulants, and enteral feedings may become mainstays of therapy. Additionally, approximately one-fifth of adults develop CF-related diabetes, and most of these patients ultimately require frequent glucose monitoring and treatment with insulin injections.9

cleanse me of this putridity within.

As my body soaks in that which

is meant to remove the foul poison,

the pills, the needles, the aerosols pulls me

down like an anchor in a deep sea,

it controls who I am, my time, my life.

I should be floating in a bubble bath

of elegance, luxury, perfection.

Instead, there are no bubbles, they all burst.

It’s just me and this bath of disease.

With permission from “The Breathing Room: The Art of Living with Cystic Fibrosis” at www.thebreathingroom.org

Understanding the Goals of Care for the CF Team

When the CFTR gene was initially described in 1989, many believed a cure for the disease was imminent.12 This hope led to great optimism regarding the approach to care for children with CF. Now, 20 years later, no cure is on the horizon.13 Widespread and consistent application of chronic treatments by patients and their families has led to increasing life expectancy, and even in the face of the discouraging results of research into a cure from gene transfer, most patients, families, and clinicians maintain an attitude of vigorous optimism toward the disease. CF clinicians generally adopt an enthusiastic approach, becoming cheerleaders for their patients, emphasizing the optimistic increases in life expectancy and vigorously encouraging their patients to keep up hope for improved survival and quality of life. This attitude is in part a response to the outdated image of CF among the general public as a killer of children, in part a strategy to encourage adherence to the increasingly time-consuming daily CF regimen, and in part an antidote to the unpredictable, waxing and waning course of the illness. CF care teams maintain a position of enthusiastic optimism in coaching patients and their families to continue the work associated with a life with CF.

Although there is much to be optimistic about with regard to CF, in some circumstances this optimism may inhibit frank discussion of the reality of life with CF. Despite the ever-expanding life expectancy, people with CF still experience significant suffering.14–24 The disease burden and physical and psychosocial distress can be seen:

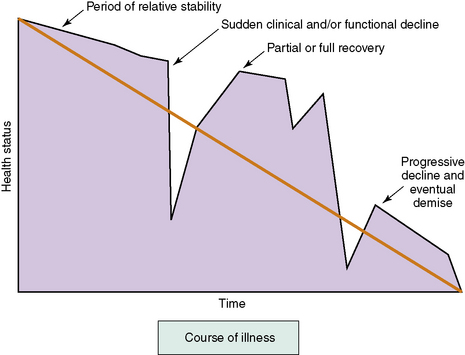

Unfortunately, even the most experienced CF medical provider is unable to predict when these episodes of acute illness and loss may occur,25 and the disease carries a large degree of uncertainty.26 Many patients with CF experience acute de-compensations, recoveries, and periods of relative stability, usually superimposed upon a gradual downward trajectory in lung function (Fig. 41-1). The functional ability of patients over time often mirrors this course. Most patients will have periodic setbacks, and while some of these setbacks will include a complete recovery, others may result in a decline in functional ability. The palliative care provider should recognize how this uncertainty and progressive loss of function will affect children and adults with CF, their families, and their medical providers.

Integrating the Palliative Care Team into CF Care

Given this mixed picture of CF, discussing palliative care has been a challenge. In the view of many CF care teams, palliative care is associated only with the medical interventions aimed at providing comfort at the end of life. As a result, specific palliative care interventions, including therapies directed at managing symptoms present in those with mild to moderate disease, are often not introduced until the patient is clearly at the end of life—often too late for the patient and family to derive the benefit of the palliative care team’s expertise. Palliative care, clearly differentiated from end of life care and integrated with curative and restorative measures, offers the best chance at limiting the burden of disease, maximizing quality of life at all stages of illness, and providing effective support to children and adults with CF and their families.27 A value added model, when provided as consulting expertise in a programmatic approach, may succeed in these situations when a more conventional approach has failed and help limit the reluctance of the CF team to involve palliative services.

The model is based on using the expertise of the palliative care team to help the CF team address the grief that often accompanies the diagnosis of a chronic life-threatening illness. It continues by emphasizing the expertise of the palliative care team in assessing and managing symptoms and assessing the burdens of treatment relative to the benefit. As symptoms progress in CF, the palliative care team assists the CF team in responding to the inevitable questions about mortality both from parents and children. The palliative team uses its expertise in discussing these matters to help the CF team be more comfortable with these issues in the context of the generally successful CF routine care. As the disease progresses, the palliative care team should further support the family in the decision making process about lung transplantation, including discussions of mortality and the benefits and burdens of an intensive treatment in pursuing the goals of care, because the current model of care leaves little time for discussion of the use of intensive measures and the goals of care.28 The palliative care team will then act in a traditional way—it is only during this phase of care that many CF teams traditionally contact the pediatric palliative care team—to assist the CF team in managing end-stage symptoms and providing high quality care at the end of life. Finally, the palliative care team will help in the bereavement process, not only for the family, but also for the long-serving and dedicated members of the CF care team (see Table 41-1).

Before the diagnosis is made

CF is a well-characterized genetic disorder with an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. Although most living patients were diagnosed following the appearance of symptoms or due to the diagnosis of a sibling, most new diagnoses will now be made through newborn screening programs, which have spread rapidly across the United States in the past few years.29 The advent of newborn screening using immunoreactive typsinogen and/or DNA analysis has resulted in a population of asymptomatic patients diagnosed in the first month of life. Earlier diagnosis has led to some improved clinical outcomes,30,31 but does carry some associated risks for families, including psychological impact of false negative and false positive results and implications of diagnosis of a genetic disease.2,32,33 Because of their experience with breaking bad news and with helping families manage the grief that may accompany the news, palliative care teams are in a good position to help CF care teams design a compassionate program for revealing the diagnosis to those parents of newborns who have a positive screen and then a confirmatory genetic analysis or sweat test.34

At the time of diagnosis

As the diagnosis is given, families must process not only the shock of the diagnosis but also the beginning of a complex new care regimen, which must be followed every day if the benefit of newborn screening is to be realized.35,36 The obvious parallel for the palliative care team is a new and unexpected diagnosis of cancer in a child, with the rapid institution of a complex and toxic therapy. While the side effects of therapy are less in the newly diagnosed child with CF, the shock and grief may be similar. CF care teams are accomplished at helping families with this news, but the advent of newborn screening brings a new group to light in the CF clinic: the largely asymptomatic child with a genetic diagnosis. The change in the experience of the diagnosis may offer an opportunity for the palliative care team to approach the CF care team with an offer to help it do the best possible job in supporting this new type of patient. While we do not recommend the palliative care team have direct contact with the family at the time of diagnosis, the interdisciplinary expertise of the palliative care team may prove to be useful to the CF care team during this time.

During routine care

Two events in particular may provide room for the palliative care team to assist the CF care team. The first is preparing it to respond to the patient and family when they bring up the limited life expectancy of someone diagnosed with CF. Many CF clinicians prefer never to talk about this issue, or to brush it aside with discussion of the progress in CF. However, it is clear that patients, especially by adolescence, recognize this issue and may very well want to talk about it.37,38 In the popular culture, CF is viewed as a progressive killer of children: movies, books, and novels about CF are inevitably tragic and highly melodramatic.39–43 Popular narratives about CF may be years out of date,44 and it is a trope that anyone portrayed on television with CF will die before the show ends. Patients and families swim in this cultural sea, and so are exposed to this inaccurate but tight link of CF with childhood death. This may cause them to be reluctant to disclose their disease to others, even friends, and so may cut them off from sources of social support that could have a positive effect of quality of life.45 Palliative care teams, as outsiders to the CF community, may be able to help the CF care team counter these popular images of CF and replace them with a more accurate portrayal of patients with CF as deeply courageous and dedicated in the face of a difficult but potentially life-affirming situation. CF medical providers do not want to be surprised when an adolescent asks about mortality, and the palliative care team may be able to develop an educational approach that explores the range of developmentally appropriate responses to a patient’s questions.

The palliative care team may also have a window of opportunity to assist the CF care team at the time of the first hospitalization for a pulmonary exacerbation. Even when most children were symptomatic at the time of diagnosis, the first pulmonary exacerbation was a time of substantial stress, during which the reality of disease progression had to be faced.46,47 Now, in the era of the asymptomatic diagnosis via newborn screening, the first exacerbation can stir up considerable anxiety for parents, and they may interpret it as a sign of more rapid decline of the child. Of course, it is the intensive and preventive approach to CF that is the cause of both the treatment for pulmonary exacerbation and the increase in life expectancy, and habituating the family to the routine of careful surveillance and vigorous treatment of any fall from the pulmonary baseline is an important goal. CF teams may not recognize the increased symbolic meaning of this first exacerbation in the era of newborn screening, as pulmonary exacerbations and their treatment are routine for the teams.

As the disease progresses

Assessment and Management of CF-Related Symptoms

Distressing symptoms are common in patients with CF14,16,19,23,24,48 and are known to increase as lung disease progresses,17,49,50 but little research defines the impact of symptoms on quality of life or on the end of life experience of these patients. General principles of symptom assessment and management can be applied to the CF population, and the interdisciplinary nature of CF care should allow for regular attention to symptoms with both physiologic and non-organic origins. Attention must be paid to the psychological impact of symptoms, particularly respiratory symptoms, as their increasing frequency and intensity typically denotes disease progression.

Respiratory Symptoms

Respiratory symptoms, such as cough and dyspnea, may be minimal or only intermittent during infancy and early childhood but in most patients progress steadily, with periods of increased cough and dyspnea occurring during respiratory exacerbations. Cough is necessary for clearance of respiratory secretions, and is encouraged in this setting, but excessive cough may be distressing and disruptive. Aerosolized therapies and airway clearance techniques facilitate cough, and are routinely recommended for maintenance of health and are intensified during respiratory exacerbations. While these treatments are intended to reduce chronic respiratory symptoms, they are thought to be burdensome by many patients.6 This perception is due in part to the extensive amount of time required to complete such treatments, but clinical experience suggests that they may also cause distressing symptoms such as pain, dyspnea, sleep disturbance, and urinary incontinence. Treatment of increased cough includes use of aerosols and airway clearance therapies, antibiotics for infection, and specific treatments for other common causes of cough, including gastroesophageal reflux disease, sinus disease, asthma, and allergies. While most pulmonologists who treat patients with CF discourage the use of antitussives because of their negative impact on airway clearance, these agents may be helpful in managing distressing cough under certain circumstances.

Hemoptysis may occur in association with cough, particularly with lower respiratory infections. Small-volume hemoptysis is generally managed with antibiotics, correction of bleeding disorders, and cautious use of or temporary suspension of aerosols and airway clearance therapies. Massive hemoptysis, which is more than 240 mL in 24 hours or recurrent bleeding of more than 100 mL per day, occurs in approximately 1% of children with CF and is unrelated to severity of lung disease. It is also associated with other respiratory complications and has a high likelihood of recurrence.51,52 Bronchial artery embolization is used for acute treatment, but recurrent and unremitting end-stage hemoptysis may require sedation and the use of dark towels and linens to minimize the sight of blood, which may help lessen the anxiety of patients, caregivers, and medical providers.

Dyspnea is commonly reported as CF lung disease progresses50 and is likely to be the most distressing symptom near the end of life. This complex symptom is related to: increased ventilatory demand due to increased dead space in abnormal CF lungs, increased respiratory effort to move air through dilated and obstructed airways, and increased muscle force required for maintenance of normal ventilation because of abnormal airway resistance and flattening of the diaphragm by hyperinflated lungs.53 In addition, the interplay between dyspnea and anxiety can be complicated.54,55 There are many approaches to the treatment of dyspnea. Enhancing airway clearance and treating infection and inflammation with standard CF therapies is a standard strategy, which may reduce acute or subacute dyspnea, ideally returning the patient back to their baseline respiratory status. With disease progression, dyspnea may become less responsive to such treatments.

For those with chronic dyspnea and more advanced lung disease, physical therapy to improve conditioning may be helpful. Respiratory support, including the use of oxygen to support gas exchange, may reduce the sensation of dyspnea. Oxygen may be used with exertion, during sleep, and on a continual basis later in the course of disease. The route of administration is typically nasal cannula, although some patients prefer to use face masks during periods of acute illness. The use of positive airway pressure for management of dyspnea, hypoxemia, and hypercapnia was typically avoided in the past because of poor outcomes of patients receiving these treatments.56–58 Applying positive pressure to airways that are abnormally dilated and impacted with thick mucus makes airway clearance, which is critical to management of respiratory infection, more difficult. In addition, ventilator modes and settings that combat hypercapnia due to respiratory failure in advanced CF lung disease are uncomfortable and typically necessitate sedative medications that interfere with the patient’s ability to communicate. However, the use of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation, typically bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP), has gained favor for patients with sleep disturbance and daytime fatigue and as a bridging therapy for patients with respiratory insufficiency awaiting lung transplantation.59,60 Full respiratory support with intubation and mechanical ventilation may also be considered for some patients with reversible causes of respiratory failure and for transplant candidates.61,62 The decision to use these treatments must be made with the knowledge that, while they may provide relief of severe dyspnea and may prolong life for those whose goal is to receive a lung transplant, their use has many associated risks that must be understood by patients and caregivers.

Decreasing the sensation of dyspnea using oral and intravenous opioids and benzodiazepines may be considered for patients with advanced lung disease. Opioids decrease respiratory drive and may act locally in the lungs to relieve dyspnea.63 However, despite evidence that these medications can be used safely in patients with respiratory diseases,54 concerns about respiratory depression in patients with advanced CF lung disease have been described and may act as barriers to effective palliation of dyspnea.10,49,53,64 Aerosolized opioids are sometimes offered, but small studies of their use to treat dyspnea do not suggest universal efficacy.63,65,66 Given the demonstrated efficacy of opioids in relieving dyspnea, concerns about their use may be alleviated by starting with very low oral or intravenous doses and titrating to effect, monitoring closely for undesirable secondary effects. This strategy also allows the patient, caregivers, and medical providers time to become more comfortable with the use of opioids to treat dyspnea. Other supportive and adjunctive therapies, including lowering ambient temperature or blowing cool air with fans, maintaining cooler ambient temperatures, positioning, relaxation techniques, and psychotherapy, may be beneficial for some patients.

Pain

Pain, including headache, sinus, chest, back, abdominal, and joint, is common in patients with CF throughout their lives.14,16,23 Careful investigation for the cause of pain is essential in selecting effective treatments. Headache may be due to cough, sinus disease, or hypercapnia in addition to the numerous other causes of headache in people without CF, and treatment should reflect the cause. Sinus pain may respond to treatment for infection with systemic or nasally instilled antibiotics or the use of intranasal steroids and saline to facilitate drainage. Surgical intervention by an otolaryngologist for severe or persistent pain may be warranted. Chest pain that originates from the lung may be due to infection, hemoptysis or pneumothorax, and is often localized and may be pleuritic. Musculoskeletal chest pain may result from frequent cough, increased thoracic volume,67 or, in those with osteoporosis related to chronic vitamin D deficiency and/or systemic steroid use, rib fractures or vertebral compression fractures.22,68 Physical therapy, pharmacologic agents, and orthopedic referral can be considered depending on the etiology of the pain. Joint pain may be due to typical injuries or causes of arthritis in the non-CF population and to quinolone use,69 but CF arthropathy, which is a diagnosis of exclusion, affects a small proportion of patients. Symptoms are typically episodic and present at times of illness and stress. Treatment may involve analgesics and anti-inflammatory medications, sometimes including disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.70,71

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Gastrointestinal manifestations of CF are numerous and include steatorrhea and malnutrition related to pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, gastroesophageal reflux, and obstructive biliary tract disease. Symptoms related to these problems include abdominal pain, constipation, anorexia, and, for a small percentage of patients, symptoms of progressive hepatobiliary disease. Abdominal pain that is associated with an increase in bowel movements, urgency or distension, should prompt optimization of pancreatic enzyme replacement. Constipation may be acute or chronic, and may be treated with prokinetic agents and oral electrolyte solutions. Distal intestinal obstruction syndrome may occur when excessively viscid intestinal contents become impacted in the distal small intestine and proximal colon, and should be suspected when pain and obstipation occur concomitantly. Treatment involves intestinal lavage and close monitoring for progression to frank bowel obstruction, which warrants surgical intervention.72,73 Gastroesophageal reflux is managed with standard therapies, including histamine-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors. Surgical treatment of reflux does not appear to confer benefit, but is considered in some cases.74 Other causes of gastrointestinal symptoms that are not specific to or more common in CF must not be overlooked.

Because of malabsorption and increased metabolic demands, patients with CF require greater caloric intake to achieve and maintain adequate nutritional status. While young patients with pancreatic insufficiency often have hearty appetites, cough and the increased work of breathing may make eating laborious and maintenance of weight difficult or impossible without medical interventions as lung disease progresses. Behavioral interventions around feeding, calorie dense oral supplements, and appetite stimulants are typically offered in a stepwise fashion while other causes of and contributors to anorexia, including gastroesophageal reflux disease, sinus disease, depression, and anxiety are addressed.75 For those who are unable to maintain acceptable nutritional status, feeding tubes may be used. Patients with advanced disease who choose to pursue lung transplantation are obligated to follow intensive nutritional interventions in order to reduce operative and recovery-related risks. Those for whom transplantation is not desired or is not an option may be offered more choices about the ongoing use of nutritional interventions.

Psychological Symptoms

Depression and anxiety are known to be problematic in chronic respiratory diseases,76 and studies suggest that their prevalence in CF is higher than in the general population.77 They may adversely impact health outcomes and quality of life, and screening for depression and anxiety might ultimately be recommended as a routine part of CF care.78–80 For patients and families affected by any chronic illness, disease-specific social support can play a vital role in coping with stress and in managing depression and anxiety. In contrast to past extensive social support available on hospital wards and summer camps, strict guidelines for infection control have led to physical isolation of patients, and thus often their families, leading to social networking and support via the Internet and other media that allow for indirect contact. For some patients and families, this is extremely effective, but for others, it leads to loneliness that may theoretically impact disease-related coping.

Treatment of depression in CF does not differ from standard treatment, apart from recognition of the role of chronic disease as a provocative factor and of the possibility of depression and other mood disorders in family members and other caregivers.81 Anxiety may be acute or chronic in nature, and in either form may be highly distressing.16 Anxiety about disease progression is common, suggesting the need for ongoing attention to this symptom. Overlap in symptoms may occur, such that anxiety may be perpetuated by dyspnea, cough, pain and fatigue, thus addressing these symptoms may reduce and indirectly treat anxiety. Medications such as beta-agonists and steroids, which are commonly used to treat CF, may also contribute to anxiety. Treatment of anxiety may initially involve cognitive behavioral therapy, psychotherapy, and complimentary techniques such as biofeedback and relaxation. Pharmacologic agents may be used in select cases, with favor given to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), with benzodiazepines considered for short-term treatment of acute anxiety77 but otherwise reserved for those with severe and unremitting symptoms or advanced lung disease.

Fatigue

Fatigue is a highly prevalent but often underappreciated symptom in patients with life-threatening illnesses55 and is common in patients with CF.16 Fatigue is reported to impact adherence to prescribed treatments82 and undoubtedly quality of life. This complex symptom is often pervasive, unresponsive to rest, limits functioning, and affects physical, cognitive and emotional stamina.55 The interaction between fatigue and other symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, pain, and depression is not well described in CF, but is presumably substantial in some patients. Treatment for fatigue is also complex and not well studied in CF, but exercise, psychosocial interventions such as psychotherapy and disease-specific support networks, complimentary and alternative therapies, improving sleep hygiene, and the use of stimulants are possible options. Fatigue may likely also be reduced indirectly by treating other symptoms.

Role of the palliative care team in symptom management

Lung Transplantation for Advanced CF Lung Disease

Lung transplantation is the most intensive treatment available for advanced CF lung disease, and is considered when a patient’s functional status and quality of life are significantly impaired and their anticipated survival is 2 years or less.83 Transplant may improve survival and quality of life for selected patients.84,85 Despite its promise as a definitive treatment for advanced CF lung disease, transplant survival outcomes are suboptimal, with a median 5-year survival of about 50% in the United States.84,86 While some patients have relatively benign operative and post-transplant courses, complications are difficult to predict and are the second leading cause of death among patients with CF.87 It is important to understand the complexity of the transplant decision, transitions in care that occur when patients decide to pursue transplant, and the interaction between curative and palliative care for patients on the transplant pathway.

Lung Transplant Decision-Making

Appropriate timing of transplant referral is difficult to predict, but there is consensus about which disease related and physiologic factors, including lung function, body mass index, functional status, and other organ involvement, should prompt consideration of referral for transplant.88,89 Because CF is a life-threatening disease with many possible treatment options and substantial uncertainty exists with regard to both survival and quality of life outcomes, it is important that patients and caregivers fully understand the risks and benefits of transplant and alternative treatment options. Informed decision-making is the clinical and ethical practice standard for complex decisions about medical care. The elements of informed decision-making90 about lung transplant are outlined in Table 41-3.

| Element of informed decision making | Selected important information for patients and caregivers |

|---|---|

| Discussion of the patient’s role in decision making |

Adapted from Braddock CH, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, et al. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. JAMA 1999;282(24): 2313–20 and Boyle MP. Adult cystic fibrosis. JAMA 2007;298(15):1787–93.

For a majority of patients who have undergone transplant, the experience of advanced lung disease unfortunately recurs. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS), another chronic progressive lung disease that is believed to be a manifestation of rejection, is the most common cause of death in lung transplant recipients surviving longer than one year after transplant.91 BOS symptoms and treatments often mirror those of CF,92 thus similar decisions about treatments to those made pre-transplant may again be faced. Second transplants are offered to and accepted by select patients, but they have poorer survival outcomes and greater associated morbidity.93

Discussions about transplant often take place with various providers, including members of the CF care team, the lung transplant team, and the palliative care team. Input from different providers may help patients and caregivers decide about transplant within the context of their own goals and values. Open communication among providers is essential so that patient and caregiver decisions can be supported. In addition, offering peer decision support by means of support groups and mentoring programs may be helpful to patients and caregivers. Issues of caregiver stress and fatigue should also be acknowledged and addressed.94,95

Interaction Between Curative and Palliative Care

Patients with advanced CF lung disease are highly symptomatic and must constantly attend to their disease in order to prevent further deterioration in health. Because of the goal of extending survival, the decision to pursue transplant may inherently change the focus of care from restorative and palliative to curative in the eyes of patients, caregivers, and medical providers.28,64 It is important to recognize that the additional stress of waiting for a transplant, with candidacy for transplant always at risk because of the development of disease complications that might preclude it and risk of dying before receiving a transplant, may have great emotional impact96 and patients with advanced lung disease remain highly symptomatic and may have little physical reserve. Discussions about transplant provide a natural opportunity to address wishes for ongoing healthcare, including hopes for survival, goals and expectations for palliation of symptoms, and desired roles of caregivers. While changing medical providers may be an additional stress, palliative care consultation during the transplant decision making process and after transplant, ideally with continuity throughout, may benefit patients, caregivers and the transplant team. Table 41-4 is a summary of ways palliative care consultants may contribute to the care of patients with CF who are making decisions about or who will undergo lung transplant.

| How can palliative care consultants contribute to the care of patients with CF during the lung transplant decision making process and after lung transplant? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Topic | During decision making process | After transplant |

| Symptom management | Assessment and recommendations for management, often in the context of need to participate in pulmonary rehabilitation programs despite profound illness and possible restrictions on use of opioids and benzodiazepines while waiting for transplant | Assessment and recommendations for management, including symptoms related to side effects of new medications |

| Psychosocial support for patient and family | Providing resources to patient and family that are focused on fears about surviving to transplant and transplant outcomes, caregiver stress and fatigue, and impact on other loved ones | Providing resources to patients who experience anxiety and uncertainty after transplant, assist in development of coping skills for those who experience complications and chronic rejection and/or graft failure |

| Informed consent | Exploring deficiencies in understanding of the transplant process and feeding back information to transplant team | Assisting with understanding of procedures and treatments related to transplant, continuing to advocate for good communication with transplant team |

| Decision support | Delineating goals of care, exploring other factors in decision making other than informed consent | Delineating goals of care in the context of health related and quality of life outcomes after transplant |

| Education for transplant team | ||

Advance Care Planning

Most patients with CF will live to become adults, necessitating a transition of decision making from surrogates to autonomous. Often in this transition, the adult patient may defer decision making to the parent who has carried that burden.7 For this reason, special care should be taken to assess the role of each patient in the decision making process. Effort should be made to transition decision making to the adolescent and young adult.

The possibility of a premature death will come as a shock to parents. While few patients give any thought to the life-threatening nature of their disease,97,98 some adolescents and young adults develop certain fantasies or beliefs about their lifespan and may develop symbolic meaning to living past a certain age.99 These expectations and perceptions may directly influence planning for the future, adherence to the therapeutic regimen, and quality of life. While advance care planning for minor children does not carry legal weight, children with CF should be included in medical decision making in a culturally and developmentally appropriate way with an effort of transition from assent to autonomy. The palliative care team can use the long-term relationships with CF care team that can facilitate multiple avenues of communication.100

A study of adults with CF revealed that most recognize the life-threatening nature of their disease and have considered the type of care they want to have if they became unable to decide for themselves, even developing specific plans about end of life care.97 While these adults discussed their plans with family members and said they would be comfortable discussing them with the CF care team, only one third had discussed advance care planning with any member of the team. It is unclear if this lack of communication is due to perceptions that these discussions will hinder hope, beliefs that they only need to occur when death is imminent, or a notion that advance care planning tools do not apply to adults with CF.

Existing advance care planning tools are generally based on an oncology model and may not fit the clinical characteristics of CF, given the different trajectory of disease and the less toxic curative and restorative disease-specific therapies. In the attempt to improve advance care planning, some CF care centers have developed CF-specific living wills or have adapted programs such as Five Wishes101 for use in CF clinical care.102

Do not resuscitate (DNR) and do not intubate (DNI) orders appear to be perceived as having limited practical use in advance care planning in CF in the United States because a DNR order is not in place for most patients until the last day or so of life.28,49 In practice, DNR and DNI orders should not be used as the sole document regarding appropriate interventions near the end of life. Instead, these orders should be used as part of meeting the goals of care of the patient and family and should be consistent with the expected outcome of the intervention.

After Death

Improved survival in CF and ongoing optimism for cure on the part of patients, caregivers, medical providers and society affects attitudes about dying from CF. While death is the inevitable outcome, it is more difficult to accept than in the past. As with many chronic diseases, death may be viewed as failure.103 Prognostic difficulties and the intensity of treatments offered to patients with CF near the end of life further complicate thinking about and anticipating death. The topics of anticipatory grief and bereavement are covered in detail elsewhere in this text; in the following we address issues specific to bereavement in CF.

Children with CF

Prognostic uncertainty and discussions about life expectancy lead to anticipatory grief in children with CF. This grief is intensified during hospitalization and during times of obvious decline as well as through observation of serious illnesses and deaths of CF peers. Children, caregivers, and medical providers should be encouraged to identify grief as an expected part of life with CF. Much as with other children with chronic life-threatening illnesses,104 children with CF are often aware they are dying even if never told directly and have concerns about impending death and separation from caregivers, family, and friends. They may also grieve the loss of function, lack of interaction with their family and peers, and changes in body image. Palliative care consultants and other providers with expertise in psychosocial support can help children communicate these concerns and find meaning as the disease progresses. They can also be helpful in educating caregivers and members of the CF care team in how to provide appropriate supports to the child.

Caregivers and other family members

For caregivers whose lives were irrevocably altered by caring for a child with CF, there may be a loss of identity and external validation related to this parenting role. Healthy siblings who may have received less attention than their siblings with CF often experience feelings of guilt105 and may be left struggling to understand their new roles within the family and their relationships with their parents. Additionally, families may experience the deaths of more than one child with CF, with each death perhaps impacting family members in different ways. Siblings who also have CF must face their own mortality and may experience anticipatory grief surrounding their own disease. Offering support and location of resources for grieving and bereaved family members can be very helpful.

1 Boyle M.P. Adult cystic fibrosis. JAMA. 2007;298(15):1787-1793.

2 Mack J.W., Wolfe J. Early integration of pediatric palliative care: for some children, palliative care starts at diagnosis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(1):10-14.

3 O’Sullivan B.P., Freedman S.D. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1891-1904.

4 Knowles M.R., Durie P.R. What is cystic fibrosis? N Engl J Med. 2002;347(6):439-442.

5 Flume P.A. Pulmonary complications of cystic fibrosis. Respir Care. 2009;54(5):618-627.

6 Sawicki G.S., Sellers D.E., Robinson W.M. High treatment burden in adults with cystic fibrosis: challenges to disease self-management. J Cyst Fibros. 2009;8(2):91-96.

7 McGuffie K., Sellers D.E., Sawicki G.S., et al. Self-reported involvement of family members in the care of adults with CF. J Cyst Fibros. 2008;7(2):95-101.

8 Mallory G.B., Fullmer J.J., Vaughan D.J. Oxygen therapy for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2005. CD003884

9 Moran F., Bradley J.M., Piper A.J. Non-invasive ventilation for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2009. CD002769

10 Kremer T.M., Zwerdling R.G., Michelson P.H., et al. Intensive care management of the patient with cystic fibrosis. J Intensive Care Med. 2008;23(3):159-177.

11 Conway S.P., Morton A., Wolfe S. Enteral tube feeding for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2008. CD001198

12 Koshland D.E.Jr. The Cystic Fibrosis Gene Story. Science. 1989;245(4922):1029.

13 Couzin-Frankel J. Genetics: The promise of a cure: 20 years and counting. Science. 2009:1504-1507.

14 Koh J.L., Harrison D., Palermo T.M., et al. Assessment of acute and chronic pain symptoms in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;40(4):330-335.

15 Palermo T.M., Harrison D., Koh J.L. Effect of disease-related pain on the health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(6):532-537.

16 Sawicki G.S., Sellers D.E., Robinson W.M. Self-reported physical and psychological symptom burden in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(4):372-380.

17 Ravilly S., Robinson W., Suresh S., et al. Chronic pain in cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 1996;98(4 Pt 1):741-747.

18 Lee A., Holdsworth M., Holland A., et al. The immediate effect of musculoskeletal physiotherapy techniques and massage on pain and ease of breathing in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2009;8(1):79-81.

19 Sermet-Gaudelus I., De Villartay P., de Dreuzy P., et al. Pain in children and adults with cystic fibrosis: a comparative study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(2):281-290.

20 Stenekes S., Hughes A., Gregoire M., et al. Frequency and self-management of pain, dyspnea, and cough in cystic fibrosis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 4(4), 2009.

21 Walker L.S., Smith C.A., Garber J., et al. Testing a model of pain appraisal and coping in children with chronic abdominal pain. Health Psychol. 2005;24(4):364-374.

22 Jones A.M., Dodd M.E., Webb A.K., et al. Acute rib fracture pain in CF. Thorax. 2001;56(10):819.

23 Festini F., Ballarin S., Codamo T., et al. Prevalence of pain in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2004;3(1):51-57.

24 Hubbard P.A., Broome M.E., Antia L.A. Pain, coping, and disability in adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis: a web-based study. Pediatr Nurs. 2005;31(2):82-86.

25 Konstan M.W., Wagener J.S., VanDevanter D.R. Characterizing aggressiveness and predicting future progression of CF lung disease. J Cyst Fibros. 2009;8(Suppl 1):S15-S19.

26 Hynson J.L. The child’s journey: transition from health to ill health. In: Goldman A., Hain R., Liben S., editors. Oxford textbook of palliative care for children. Oxford University Press, 2006.

27 Bourke S., Doe S., Gascoigne A., et al. An integrated model of provision of palliative care to patients with cystic fibrosis. Palliat Med. 2009.

28 Dellon E.P., Leigh M.W., Yankaskas J.R., et al. Effects of lung transplantation on inpatient end of life care in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2007;6(6):396-402.

29 Southern K.W., Merelle M.M., Dankert-Roelse J.E., et al. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2009. CD001402

30 Linnane B.M., Hall G.L., Nolan G., et al. Lung function in infants with cystic fibrosis diagnosed by newborn screening. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(12):1238-1244.

31 Rock M.J. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. Clin Chest Med. 2007;28(2):297-305.

32 Lewis S., Curnow L., Ross M., et al. Parental attitudes to the identification of their infants as carriers of cystic fibrosis by newborn screening. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42(9):533-537.

33 Comeau A.M., Parad R., Gerstle R., et al. Challenges in implementing a successful newborn cystic fibrosis screening program. J Pediatr. 2005;147(Suppl 3):S89-S93.

34 Grob R. Is my sick child healthy? Is my healthy child sick? Changing parental experiences of cystic fibrosis in the age of expanded newborn screening. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(7):1056-1064.

35 Collins M.S., Abbott M.A., Wakefield D.B., et al. Improved pulmonary and growth outcomes in cystic fibrosis by newborn screening. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2008;43(7):648-655.

36 Stick S.M., Brennan S., Murray C., et al. Bronchiectasis in infants and preschool children diagnosed with cystic fibrosis after newborn Screening. J Pediatr. 2009;155(5):623-628. e1.Epub

37 Christian B.J., D’Auria J.P., Moore C.B. Playing for time: adolescent perspectives of lung transplantation for cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Health Care. 1999;13(3 Pt 1):120-125.

38 Powers P.M., Gerstle R., Lapey A. Adolescents with cystic fibrosis: family reports of adolescent health-related quality of life and forced expiratory volume in one second. Pediatrics. 2001;107(5):E70.

39 Merullo R.A. Little love story. New York: Vintage Books, 2005.

40 Mitchell I., Nakielna E., Tullis E., Adair C. Cystic fibrosis: end-stage care in Canada. Chest. 2000;118(1):80-84.

41 Woodson M. Turn it into glory: a mother’s moving story of her daughter’s last great adventure. Minneapolis: Bethany House Publishers, 1991.

42 McDaniel L.A. Time to die. New York: Laurel Leaf, 1992.

43 Pitts D. Living on borrowed time: life with cystic fibrosis. Bloomington, Ind: AuthorHouse, 2007.

44 Deford F. Alex: the life of a child. Nashville: Rutledge Hill Press, 1983.

45 Lowton K. Only when I cough? Adults’ disclosure of cystic fibrosis. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(2):167-186.

46 Bluebond-Langner M. The private worlds of dying children. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978.

47 Bluebond-Langner M. In the shadow of illness: parents and siblings of the chronically ill child. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996.

48 Smith J.A., Owen E.C., Jones A.M., et al. Objective measurement of cough during pulmonary exacerbations in adults with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2006;61(5):425-429.

49 Robinson W.M., Ravilly S., Berde C., et al. End-of-life care in cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 1997;100(2 Pt 1):205-209.

50 Yankaskas J.R., Marshall B.C., Sufian B., et al. Cystic fibrosis adult care: consensus conference report. Chest. 2004;125(Suppl 1):1S-39S.

51 Barben J.U., Ditchfield M., Carlin J.B., et al. Major haemoptysis in children with cystic fibrosis: a 20-year retrospective study. J Cyst Fibros. 2003;2(3):105-111.

52 Flume P.A., Strange C., Ye X., et al. Pneumothorax in cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2005;128(2):720-728.

53 Orenstein D.M., Rosenstein B.J., Stern R.C. Cystic fibrosis medical care. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Williams, 2000.

54 Luce J.M., Luce J.A. Perspectives on care at the close of life. Management of dyspnea in patients with far-advanced lung disease: “Once I lose it, it’s kind of hard to catch it. JAMA. 2001;285(10):1331-1337.

55 Ullrich C.K., Mayer O.H. Assessment and management of fatigue and dyspnea in pediatric palliative care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(5):735-756. xi

56 Berlinski A., Fan L.L., Kozinetz C.A., et al. Invasive mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory failure in children with cystic fibrosis: outcome analysis and case-control study. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2002;34(4):297-303.

57 Davis P.B., di Sant’Agnese P.A. Assisted ventilation for patients with cystic fibrosis. JAMA. 1978;239(18):1851-1854.

58 Texereau J., Jamal D., Choukroun G., et al. Determinants of mortality for adults with cystic fibrosis admitted in intensive care unit: a multicenter study. Respir Res. 2006;7:14.

59 Madden B.P., Kariyawasam H., Siddiqi A.J., et al. Noninvasive ventilation in cystic fibrosis patients with acute or chronic respiratory failure. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(2):310-313.

60 Noone P.G. Non-invasive ventilation for the treatment of hypercapnic respiratory failure in cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2008;63(1):5-7.

61 Bartz R.R., Love R.B., Leverson G.E., et al. Pre-transplant mechanical ventilation and outcome in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22(4):433-438.

62 Sood N., Paradowski L.J., Yankaskas J.R. Outcomes of intensive care unit care in adults with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(2):335-338.

63 Brown S.J., Eichner S.F., Jones J.R. Nebulized morphine for relief of dyspnea due to chronic lung disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(6):1088-1092.

64 Robinson W. Palliative care in cystic fibrosis. J Palliat Med. 2000;3(2):187-192.

65 Currow D.C., Ward A.M., Abernethy A.P. Advances in the pharmacological management of breathlessness. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2009;3(2):103-106.

66 Graff G.R., Stark J.M., Grueber R. Nebulized fentanyl for palliation of dysp-nea in a cystic fibrosis patient. Respiration. 2004;71(6):646-649.

67 Ross J., Gamble J., Schultz A., et al. Back pain and spinal deformity in cystic fibrosis. Am J Dis Child. 1987;141(12):1313-1316.

68 Yen D., Hedden D. Multiple vertebral compression fractures in a patient treated with corticosteroids for cystic fibrosis. Can J Surg. 2002;45(5):383-384.

69 Sendzik J., Lode H., Stahlmann R. Quinolone-induced arthropathy: an update focusing on new mechanistic and clinical data. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;33(3):194-200.

70 Dixey J., Redington A.N., Butler R.C., et al. The arthropathy of cystic fibrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47(3):218-223.

71 Schidlow D.V., Goldsmith D.P., Palmer J., et al. Arthritis in cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59(4):377-379.

72 Dray X., Bienvenu T., Desmazes-Dufeu N., et al. Distal intestinal obstruction syndrome in adults with cystic fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(6):498-503.

73 Turcios N.L. Cystic fibrosis: an overview. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39(4):307-317.

74 Boesch R.P., Acton J.D. Outcomes of fundoplication in children with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42(8):1341-1344.

75 Stallings V.A., Stark L.J., Robinson K.A., et al. Evidence-based practice recommendations for nutrition-related management of children and adults with cystic fibrosis and pancreatic insufficiency: results of a systematic review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(5):832-839.

76 Shanmugam G., Bhutani S., Khan D.A., et al. Psychiatric considerations in pulmonary disease. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(4):761-780.

77 Cruz I., Marciel K.K., Quittner A.L., et al. Anxiety and depression in cystic fibrosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;30(5):569-578.

78 Havermans T., Colpaert K., Dupont L.J. Quality of life in patients with cystic fibrosis: association with anxiety and depression. J Cyst Fibros. 2008;7(6):581-584.

79 Quittner A.L., Barker D.H., Snell C., et al. Prevalence and impact of depression in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2008;14(6):582-588.

80 Riekert K.A., Bartlett S.J., Boyle M.P., et al. The association between depression, lung function, and health-related quality of life among adults with cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2007;132(1):231-237.

81 Glasscoe C., Lancaster G.A., Smyth R.L., et al. Parental depression following the early diagnosis of cystic fibrosis: a matched, prospective study. J Pediatr. 2007;150(2):185-191.

82 Prasad S.A., Cerny F.J. Factors that influence adherence to exercise and their effectiveness: application to cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2002;34(1):66-72.

83 Yankaskas J.R., Knowles M.R., editors. Clinical pathophysiology and manifestations of lung disease: cystic fibrosis in adults. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1999.

84 Egan T.M., Detterbeck F.C., Mill M.R., et al. Long term results of lung trans-plantation for cystic fibrosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22(4):602-609.

85 Gee L., Abbott J., Hart A., et al. Associations between clinical variables and quality of life in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2005;4(1):59-66.

86 Egan T.M., Murray S., Bistami R.T., et al. Development of the new lung allocation system in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(5):1212-1227.

87 Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry: Annual Data Report. 2006. www.cff.org/research/ClinicalResearch/PatientRegistryReport. Accessed December 2009

88 Egan T.M., Kotloff R.M. Pro/Con debate: lung allocation should be based on medical urgency and transplant survival and not on waiting time. Chest. 2005;128(1):407-415.

89 Yankaskas J.R., Mallory G.B.Jr. Lung transplantation in cystic fibrosis: consensus conference statement. Chest. 1998;113(1):217-226.

90 Braddock CHr, Edwards K.A., Hasenberg N.M., et al. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. JAMA. 1999;282(24):2313-2320.

91 Song M.K., De Vito Dabbs A., Studer S.M., et al. Course of illness after the onset of chronic rejection in lung transplant recipients. Am J Crit Care. 2008;17(3):246-253.

92 Song M.K., De Vito Dabbs A.J. Advance care planning after lung transplantation: a case of missed opportunities. Prog Transplant. 2006;16(3):222-225.

93 Osaki S., Maloney J.D., Meyer K.C., et al. Redo lung transplantation for acute and chronic lung allograft failure: long-term follow-up in a single center. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34(6):1191-1197.

94 Claar R.L., Parekh P.I., Palmer S.M., et al. Emotional distress and quality of life in caregivers of patients awaiting lung transplant. J Psychosom Res. 2005;59(1):1-6.

95 Lefaiver C.A., Keough V.A., Letizia M., et al. Quality of life in caregivers providing care for lung transplant candidates. Prog Transplant. 2009;19(2):142-152.

96 Vermeulen K.M., Bosma O.H., Bij W., et al. Stress, psychological distress, and coping in patients on the waiting list for lung transplantation: an exploratory study. Transpl Int. 2005;18(8):954-959.

97 Sawicki G.S., Dill E.J., Asher D., et al. Advance care planning in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(8):1135-1141.

98 Sawicki G.S., Sellers D.E., McGuffie K., et al. Adults with cystic fibrosis report important and unmet needs for disease information. J Cyst Fibros. 2007;6(6):411-416.

99 Auclair C. The Fog of Math. SVB: Newsletter of the Adult CF Committee of Quebec. 2007;31:5.

100 Freyer D.R., Kuperberg A., Sterken D.J., Pastyrnak S.L., Hudson D., Richards T. Multidisciplinary care of the dying adolescent. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;15(3):693-715.

101 Five Wishes. 2007. www.agingwithdignity.org. Accessed December 2009

102 McCollum A.T., Schwartz A.H. Social work and the mourning parent. Soc Work. 1972;17:25-36.

103 Liben S., Papadatou D., Wolfe J. Paediatric palliative care: challenges and emerging ideas. Lancet. 2008;371(9615):852-864.

104 Waechter E.H. Children’s awareness of fatal illness. Am J Nurs. 1971;7(6):1168-1172.

105 Fanos J.H. Sibling loss. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, 1996.