16

Cystic and neuroendocrine tumours of the pancreas

Introduction

Although pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma accounts for the majority of patients with neoplastic disease of the pancreas, over the last two decades there has been an increasing recognition of cystic and neuroendocrine pancreatic neoplasms.1 The aim of this chapter is to examine these tumours in more detail, with particular emphasis on intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (NETs). Where possible, evidence-based recommendations for the investigation and management of these tumours will be provided.

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms

IPMNs have only been recognised as separate entities to ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas since 1982,2 subsequent to which the World Health Organisation clarified their definition.3 They are defined as a grossly visible, mucin-producing epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas, which arises from within the main pancreatic duct (main-duct IPMN) or one of its branches (branch-duct IPMN), and most often but not always has a papillary architecture. They are distinguished from mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs) by the absence of ovarian-type stroma.4

The incidence (95% confidence interval) is estimated at 2.04 (1.28–2.80) per 100 000 population; however, this increases significantly after the sixth decade.5 The precise aetiology remains unknown, although an association with extrapancreatic primaries (10%), most commonly colorectal, breast and prostate, has been reported, but this is not significantly different to that seen with primary pancreatic adenocarcinoma.6 IPMN has also been shown to be a predictor of pancreatic cancer as compared to other intra-abdominal pathologies, with an odds ratio of 7.18.7

Clinical presentation

IPMNs most commonly present with symptoms related to pancreatic duct obstruction. The Johns Hopkins group reported their experience comparing the presentation and demographics to those patients presenting with pancreatic adenocarcinoma.8,9 Although the mean age of presentation was similar to that of pancreatic adenocarcinoma (seventh decade), the clinical presentation was significantly different. Of the 60 patients with IPMNs, 59% presented with abdominal pain but only 16% presented with obstructive jaundice, compared to 38% and 74% of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, respectively.8 This is in spite of the fact that only five of the 60 patients with IPMNs had tumours within the body or tail.8 In addition, those with IPMNs were more likely to have been smokers and 14% had suffered previous attacks of acute pancreatitis (compared to 3% of those with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma).8 Weight loss was a prominent factor reported in 29% of patients with IPMNs.9 Symptoms associated with invasive malignancy included the presence of jaundice, weight loss, vomiting9 and diabetes.10 Patients with invasive IPMNs were a mean of 5 years older (68 vs. 63 years) compared to those with non-invasive IPMNs.9 This led the authors to conclude that IPMN was a slow-growing tumour with a significant latency to develop invasive disease.9 Increasingly, an important presentation is the incidental finding due to cross-sectional imaging for other medical indications. IPMN was the final diagnosis in 36% of pancreatic ‘incidentalomas’ that underwent pancreatico-duodenectomy.11

Investigation

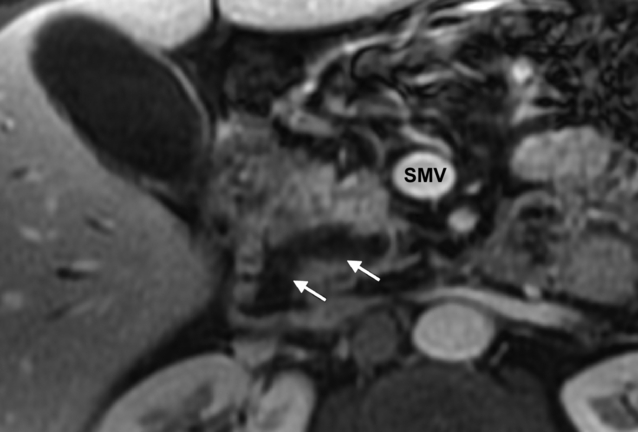

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) form the mainstay of non-invasive radiological imaging of suspected IPMN. The classical features of main-duct IPMN are of a grossly dilated main pancreatic duct (Fig. 16.1), while branch-type IPMN can present with small cystic lesions that may appear in a ‘grape-like’ configuration.12 Although MRI and CT have been shown to identify accurately tumour location and communication with the pancreatic duct, the detection of invasive malignancy remains problematic.13–15 Radiological features associated with malignancy include the presence of a solid mass, biliary dilatation > 15 mm and increasing size of either the tumour for branch-type IPMN (growth rate > 2 mm/year)16 or main pancreatic duct diameter for main-duct IPMN.15 18F-labelled fluorodeoxyglucose CT/positron emission tomography (PET) has recently been shown in small case series to differentiate benign from malignant IPMNs. In a series of 29 patients, a standardised uptake value of > 2.5 was shown to have a 96% accuracy in determining the presence of malignancy.17 Differentiating IPMN from other cystic neoplasms (particularly branch-type IPMN from MCN) can be difficult and the importance of considering the clinical picture cannot be underestimated, particularly the patient’s age, gender and history of pancreatitis or genetic syndromes.18 Radiologically, localisation within the uncinate process, detection of non-gravity-dependent luminal filling defects (papillary projections) or grouped gravity-dependent luminal filling defects (mucin), and upstream dilatation of ducts (MCN ducts are normal) all favour the diagnosis of branch-type IPMN.19 Differentiating diffuse main-duct IPMN from chronic obstructive pancreatitis can be challenging radiologically19 (clinically, patients with IPMN tend to be 20 years older and lack a history of heavy alcohol use), but high-quality cross-sectional imaging looking for endoluminal filling defects (either mucin or papillary proliferations), cystic dilatation of collateral branches (particularly within the uncinate process), communication of dilated ducts with normal ducts without evidence of an obstructing lesion or a widely open papilla (Fig. 16.1) all favour IPMN.19

Figure 16.1 MRI (post-gadolinium, T1-weighted, fat-saturated) image of the pancreas. The white arrows indicate a dilated pancreatic duct with a widely open ampulla consistent with a main-duct intraductal papillary neoplasm. SMV, superior mesenteric vein. Histology is shown in Fig. 16.2.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has the advantage of being able to sample cystic fluid and biopsy solid lesions at the time of assessment, although its utility over cross-sectional imaging has recently been questioned.20 Features seen at EUS suggestive of malignancy include main duct > 10 mm (for main-duct IPMN), while suspicious features for branch-type IPMN include tumour diameter greater than 40 mm associated with thick irregular septa and mural nodules > 10 mm.21 In a series of 74 patients with IPMNs of which 21 (28%) had invasive carcinoma, the sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of EUS fine-needle aspiration in predicting invasive carcinoma were 75%, 91% and 86%, respectively.22 In this particular study, the elevated levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 within cyst fluid did not predict the presence of malignancy.22 Importantly, the absence of mucin does not exclude IPMN.23 While the presence of necrosis is the only feature that is strongly suggestive of invasive carcinoma, abundant background inflammation and parachromatin clearing are suspicious for carcinoma in situ.23

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) can be used in the diagnosis of IPMN, although MRI (including the use of gadolinium) is increasingly replacing it (Fig. 16.1). The observation at ERCP of mucin protruding from a widely open papilla is diagnostic.24 Biopsies and aspiration of ductal contents can be obtained; however, the yield is less than 50%.24

Although there are no tumour markers specific to IPMN, serum CA19-9 but not CEA has been shown to be an independent predictor of malignancy.10

Given the increasing frequency of diagnosis and relatively low rate of malignancy within branch-duct IPMN, clinicoradiological scoring systems have been proposed.10,25 Fujino et al. have proposed a clinicoradiological scoring system for predicting the presence of invasive malignancy in patients with both branch- and main-duct IPMNs (based on an analysis of 64 patients who underwent resection).10 It consists of seven factors (Table 16.1), each with an assigned score. A cut-off of 3 or more predicts malignancy with a sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and overall accuracy of 95%, 82%, 91%, 90% and 91%, respectively. No patient with a score of > 4 had benign lesions, while no patient with a score of < 2 had malignancy. Clearly, if this system is validated and further refined with larger numbers of patients, this may prove a very simple and useful predictor of underlying malignancy. In a large study by Hwang et al.,25 237 patients with branch-duct IPMN who underwent resection were studied. Using multivariate analysis to identify independent predictors of either malignancy or invasiveness, formulae were created. However, the presence of a mural nodule, elevated serum CEA or cyst size greater than 28 mm was sufficient to conclude that there was underlying malignant change or invasion and an indication for surgery.25 An important point when considering the use of these scoring systems is that the radiological measurement varies by scan modality and may not correlate well with the final pathological measurement.26

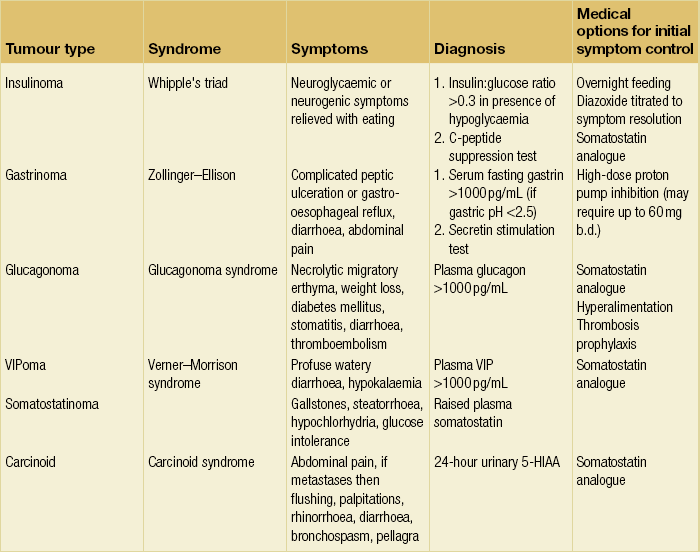

Table 16.1

Proposed scoring system10 to predict malignancy in patients with suspected intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas

| Variable | Score |

| Patulous papilla | 1 |

| Jaundice | 1 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 |

| Tumour size ≥ 42 mm | 1 |

| Main-duct type | 2 |

| Main duct ≥ 6.5 mm | 3 |

| CA 19-9 ≥ 35 units/mL | 3 |

Pathology

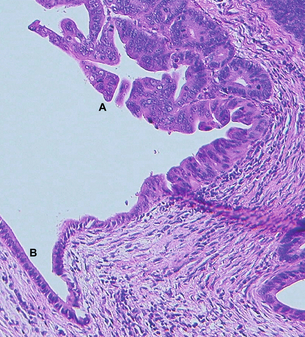

IPMNs involve the head of the gland in 70% of cases, while 5–10% are spread diffusely throughout the gland, and the rest are located within the body and tail.27 On sectioning, the involvement can be diffuse or segmented, with projections of papillary epithelium (Fig. 16.2) and tenacious thick mucin within the involved dilated ducts. The projections and mucin can extend along the ducts and into the surrounding structures, including the ampulla, duodenum and bile duct. Communication of the main pancreatic duct with the cystic lesion can usually be established. IPMNs are subclassified into main duct, branch type or mixed, depending on site of origin. This is important as branch-type neoplasms are less likely to be associated with malignancy.24 Surrounding pancreatic parenchyma may appear firm and hard due to scarring and atrophy from obstructive chronic pancreatitis secondary to the tumour. The presence of gelatinous or solid nodules should raise the suspicion of an invasive component. Microscopically, the most typical appearance is of mucin-secreting columnar epithelium with variable atypia (low-, moderate-, high-grade dysplasia or invasive carcinoma).27 The growth pattern varies from flat ducts (ectasia) through to prominent papillae. The tumour tends to follow the pancreatic ducts and can be multifocal in 20–30% of patients.27 IPMNs can contain intestinal, gastric or, less commonly, pancreatico-biliary type differentiation. The gastric type are more often associated with branch-type IPMN and would seem to be associated with a different (lower) malignant potential, growth pattern and type of mucin production compared to the intestinal type.28,29 Invasive carcinoma occurs focally and is thought to result from a stepwise progression through increasingly dysplastic lesions.27 The invasive growth pattern can be muconodular (colloid) or a conventional ductal pattern and would appear to be related to the underlying cellular differentiation (intestinal vs. pancreatico-biliary, respectively).27,29

Figure 16.2 Haematoxylin-and-eosin-stained section from the pancreatico-duodenectomy specimen of the patient in Fig. 16.1. Label A is in the lumen of the proximal pancreatic duct with adjacent proliferation of severely dysplastic glandular epithelium with intraluminal papillary growth, but no stromal invasion in this area. Elsewhere in the specimen focal stromal invasion was identified. Label B indicates remnant low columnar non-neoplastic epithelium of the duct.

Pathologically, differentiating IPMN from other cystic neoplasms of the pancreas is important. The absence of ovarian stroma helps to separate IPMN from MCN.4 For lesions between 0.5 and 1 cm, differentiating pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) from IPMN is difficult. IPMNs tend to have taller and more complex papillae and are associated with abundant luminal mucin.27 The presence of coarse and stippled chromatin with a smooth nuclear membrane will differentiate cystic pancreatic endocrine neoplasms from IPMNs.27

Management

The same IAP guidelines4 recommended that all patients with symptomatic branch-duct IPMNs underwent resection on the basis that it would alleviate symptoms and because the literature would suggest that there is a higher rate of malignancy in patients who are symptomatic (risk of invasive malignancy 30%).4 For asymptomatic patients4 it was recommended that patients with tumours ≥ 30 mm or with mural nodules underwent resection due to the increased risk of malignancy. Although risk factors for malignancy have been identified by more than one study using multivariate analysis,10,30these have been based on small numbers of patients. Nagai et al. have challenged this approach, advocating aggressive surgical resection for branch-type IPMNs, arguing that the identified risk factors do not have a high enough negative predictive value, that survival is significantly compromised in those with invasive disease, and that pancreatic surgery can be performed with a low morbidity and mortality in experienced centres.31

Since publication of the IAP guidelines,4 a large dual-centre study32 consisting of 145 patients with branch-duct IPMNs who underwent resection has been reported. Of these 145 patients, 22% had malignant disease (in situ or invasive) and 40% were asymptomatic. Although symptoms per se were not found to be a predictor of malignancy on univariate analysis, jaundice and abdominal pain were more likely to be associated with malignancy. Radiologically malignant tumours were larger, and on pathological analysis the presence of a thick wall, nodularity and size ≥ 30 mm were all significantly associated with malignancy. It is important to note, however, that other than size these factors were not assessed radiologically. In addition, there was a significant discrepancy between radiologically and pathologically measured size (radiological measurement was consistently 15% greater). The authors concluded that their results supported the IAP guidelines, particularly with regard to non-surgical management of those that were asymptomatic with no concerning features of malignancy.

Given that even branch-duct IPMN would appear to be a premalignant lesion, albeit a slow-growing one, one has to know the outcome from long-term follow-up if conservative management is to be successful. In two large prospective contemporary studies33,34 of branch-duct IPMNs, in which indications for resection were based on IAP guidelines, patients were allocated to a surgical or intensive follow-up arm. In both studies 18% of patients met the criteria for surgery at initial presentation. Of these patients, the final histology was malignant (in situ or invasive disease) in 3 of 2033 and 8 of 3434 patients. In those patients submitted to follow-up, intensive regimens (3–6 monthly for the first 2 years) were used in both studies, including combinations of CT, EUS and MRI. Between 5% and 12% of patients subsequently progressed to surgery during follow-up (median 12–18 months). Of these patients, 0 of 533 and 2 of 1834 had malignant disease. All remaining patients (n = 8433 and n = 13234) that were followed remained alive during median follow-up periods of 30 months, with no deaths attributable to their disease.

For those patients in whom surgery is indicated, the decision regarding the extent of pancreatic resection and nodal dissection needs to be decided. Fujino et al. reviewed the outcome in 57 patients who underwent surgical resection for IPMN.35 Their approach was to perform a localised resection where pre-resection imaging revealed localised disease, using intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) to determine the point of pancreatic transection, while in patients with diffuse disease a total pancreatectomy was performed. Frozen section was performed and for patients with invasive carcinoma a radical resection was performed. Where non-invasive disease was detected, a tumour-free margin was sufficient. Of the 33 patients with main-duct IPMNs, 14 met the pre-resection criteria for total pancreatectomy. All 24 patients with branch-duct tumours underwent partial resections, although two subsequently required completion pancreatectomy for complications. Correlating the final pathological assessment with the IOUS indicated an accuracy of ductal spread of 74% for main-duct tumours and 96% for branch-duct tumours. Frozen section was performed in 30 of the patients who underwent partial resection and in 29 patients it correlated with the final result. Only one patient had invasive malignancy at the transected surface, while a further two patients who did not have frozen section assessment had invasive malignancy at the resection margin.

Although Fujino et al.35 report frozen section to be very accurate, it can be a challenging undertaking for the pathologist. However, not all positive margins require resection. Current recommendations from the IAP guidelines4 are that, in the presence of adenoma or borderline atypia, no further resection is required, but if in situ or invasive carcinoma is present, then further resection should be performed. However, what has not yet been addressed in the literature is the effect of potentially spilling invasive carcinoma cells (i.e. cutting through invasive tumour) during surgery and the effect this has on long-term outcomes. This is particularly important as increasingly limited resections are being reported for low-grade lesions within the pancreas with good long-term outcomes. However, for main-duct IPMNs, the authors have advised caution for exactly this reason, given the risk of a positive resection margin and subsequent recurrence.36

Outcome

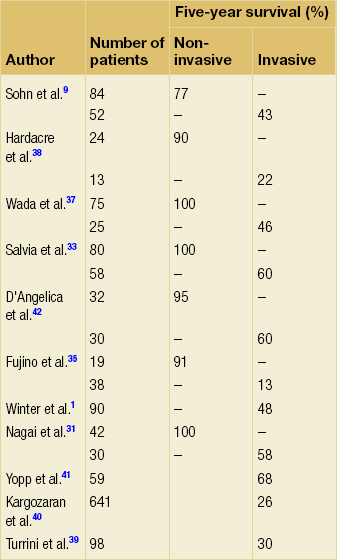

The main determinant of survival following resection is the presence of invasive disease (Table 16.2). The 5-year survival for those with non-invasive disease is 77–100%9,31,33,35,37,38 vs. 13–68%1,9,31,33,35,37–41 for those with invasive disease. Other factors that have been reported to be associated with poor survival in those with invasive disease include the presence of jaundice,42 tumour type (tubular worse than colloid),9,29,41,42 vascular invasion,39,40,42 perineural invasion,39 poorly differentiated tumours,39 percentage of tumour that was invasive39,42 and positive lymph node involvement,9,37,39,42 which has been reported in up to 41%37 of patients with invasive disease. Invasive branch-type tumours have been shown to have similar survival to those with invasive main-duct disease42 and margin status has not been associated with worse long-term outcome.9,39,40,42 In studies that have performed a multivariate analysis with adequate numbers of patients per variable, lymph node involvement,39,41 invasive component > 2 cm,39 absence of weight loss,39 morphological subtype29 and tubular carcinoma41 have been found to be independent predictors of poorer outcome. Invasive IPMN would still appear to have a better prognosis than pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma,31,37,41 although the tubular subtype may not.41 The role of adjuvant therapy for those with invasive disease has not been addressed in formal trials. Outcomes from retrospective series have been analysed,39,41 yet the role of either radiotherapy or chemotherapy remains unclear and currently cannot be recommended as the standard of care.

Table 16.2

Survival following resection for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms by presence of invasion

Recurrence following resection can be classified as disseminated (including peritoneal disease) or local (within the pancreatic remnant). White et al. have reported on 78 patients who underwent resection for non-invasive IPMNs over a 13-year period.43 The median follow-up was 40 months. Only six patients (7.7%) developed local recurrence, three of whom underwent further resection and remained under active follow-up. Importantly, time to recurrence was extremely variable, with a range of 8–62 months, indicating that long-term surveillance of the pancreatic remnant is required. There was a significant association of recurrence with positive margins,43 although this has not been shown elsewhere.9 Given the significant morbidity and late mortality associated with total pancreatectomy,35 the authors favoured follow-up of the remnant as opposed to total pancreatectomy.43

In a large series of 145 patients who underwent resection for branch-type IPMNs, 6.9% of patients developed recurrence.32 Four of 139 patients with non-invasive disease developed local recurrence at a mean follow-up of 34 months, while 6 of 16 patients with invasive carcinoma developed distant disease (three also had local recurrence) at a mean follow-up of 24 months (all died within 2 years of recurrence). These findings have been further supported by Park et al., who identified invasive disease, elevated CA19-9 and tumour location within the head as independent risk factors for recurrence.44

Given that recurrence would seem to occur most commonly within the pancreatic remnant, Tomimaru et al.45 have proposed performing a pancreatico-gastrostomy to allow easy endoscopic follow-up of the duct. Additionally, the association of IPMNs with other gastrointestinal malignancies4 should alert physicians to investigate new gastrointestinal symptoms promptly.

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (PNETs) are rare tumours with a reported incidence of 0.2–0.4 per 100 000, although post-mortem studies have reported PNETs in up to 10% of the population.46 Eighty-five per cent of PNETs are non-syndromic (non-functional), with the rest comprised of syndromic tumours47 of which carcinoid, insulinoma and gastrinoma are the most common.48 The aetiology is poorly understood and although the majority of tumours are sporadic, there are associations with several hereditary syndromes, including Von Hippel–Lindau, multiple endocrine neoplasia-1 (MEN-1), neurofibromatosis type 1 and tubular sclerosis.49

Clinical presentation

The mode of presentation is dependent on the functional state of the tumour. Non-functioning tumours may present incidentally, whereas symptoms are usually related to mass effect or the presence of metastatic disease. For those tumours associated with a syndrome, this will be related to the specific hormone production (Table 16.3).

Investigations

Biochemical

Specific fasting gut hormones can be measured for functional tumours.48 For suspected insulinoma and carcinoid, this would include fasting glucose, insulin, C-peptide and 24-hour urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA).48 In addition, in the majority of PNETs, including non-functional tumours,48 serum chromogranin A (protein produced from cells arising from the neural crest) will be elevated. Although chromogranin A is sensitive, it is not highly specific and those interpreting the test must be aware of causes of false-positive results.50 The degree of elevation of chromogranin A has been shown to correlate with burden of disease (although not with gastrinomas), response to treatment and recurrence.50

Other investigations such as calcium, parathyroid hormone, calcitonin and thyroid function tests should also be considered, particularly if there is a history that suggests MEN-1.48 For those in whom a hereditary component is suspected, referral to an appropriate genetic service for further investigation should be initiated.

Radiology

For non-functioning tumours, where localisation is often not an issue, a high-quality arterial and portal venous phase CT will be sufficient to direct therapy, particularly in determining if surgery is indicated. Features suggestive of a PNET on CT include the presence of a hypervascular or hyperdense lesion within the pancreas; however, they can also appear cystic or contain calcifications.51 The presence of a large incidental mass within the pancreas, particularly without vascular encasement or desmoplastic reaction, should also alert the clinician to the possibility of a PNET.51

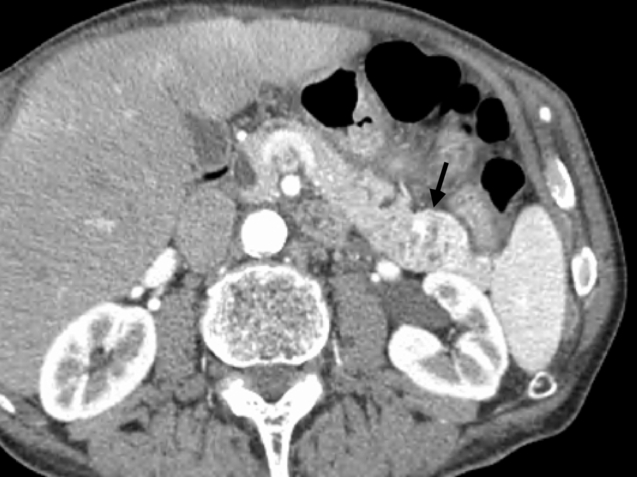

Although somatostatinomas, VIPomas and glucagonomas tend to be large and easily identified and staged by contrast-enhanced CT, this is often not the case for insulinomas and gastrinomas, unless there is widespread metastatic disease. Most insulinomas are under 2 cm and solitary. On CT they tend to be hypervascular (Fig. 16.3) with either uniform or target enhancement; however, given that they are often non-contour conforming, detection of the vascular blush is essential to localise them (the chance of detection can be maximised by timing the images 25 seconds after contrast injection).51 MRI features include low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and they are particularly well seen on fat-suppressed (T1- and T2-weighted) images.51 In contrast to insulinoma, gastrinoma can be multiple and extrapancreatic (located within the gastrinoma triangle; the junction between neck and body of the pancreas medially, the junction of the second and third parts of the duodenum inferiorly and the junction of the common bile duct and cystic duct superiorly).52 On radiological examination, they tend to be less vascular than insulinoma.51 There is a high rate (70–80%) of lymph node and hepatic metastases.51 The sensitivity of CT in the detection of gastrinoma is related to size and can be as low as 30–50%.52 Although slightly better figures have been reported for insulinomas, this can be increased to 94% with the use of thin formats and, with the addition of endoscopic ultrasound, sensitivities of 100% have been reported.52

Figure 16.3 A 78-year-old man presented with neuroglycaemic symptoms. Biochemical testing confirmed an insulinoma. Arterial phase computed tomography revealed a hypervascular lesion in the tail of the pancreas (black arrow). Laparoscopic spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy was performed. Histology confirmed malignant, node-positive neuroendocrine tumour consistent with an insulinoma. After 4 years with no symptoms the patient re-presented with symptoms of hypoglycaemia. Further investigation revealed an isolated nodal recurrence adjacent to the superior mesenteric artery. The patient has recently undergone a completion radical antegrade modular distal pancreatico-splenectomy with resolution of hypoglycaemic symptoms.

Endoscopic ultrasound is particularly useful for imaging the duodenal wall, regional lymph nodes and the pancreatic head, and has reported sensitivities of 79–100%, but is operator dependent.52 Equally, the use of intraoperative ultrasound has also been shown to be useful, particularly in gastrinomas, by identifying occult multiple primaries or metastatic disease. The sensitivity for detecting small lesions in the pancreatic head is reported to be as high as 97%.52

PNET hepatic metastases often appear as low-attenuation lesions on pre-contrast CT and hypervascular lesions on post-contrast imaging.52 It is, however, important to perform a hepatic arterial phase as they can be isointense with normal parenchyma on portal venous imaging. MRI appearances of hepatic metastases are usually of low signal intensity lesions on T1 and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Importantly, 15% of hepatic metastases were only seen on immediate post-gadolinium imaging.

In addition to standard radiological imaging, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS) is also very useful in the staging and treatment of PNETs (with the exception of insulinomas).53 This works on the principle that PNETs express somatostatin receptors. The use of a somatostatin analogue labelled with a radioactive isotope (of which there are several) allows a functional image to be obtained but it requires somatostatin analogues to be stopped prior to the scan. As a single investigation, it is probably the most sensitive for the detection of PNETs; however, equivalence can be achieved with a combined approach of standard radiology (particularly MRI and EUS), which has the advantage of providing a detailed anatomical analysis.54 SRS does, however, offer the advantage of reflecting functionality, which is important if treatment doses of radiolabelled somatostatin analogues or meta-iodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) are to be used. 18F-labelled deoxyglucose PET has not been shown to be useful for the majority of PNETs; however, the development of newer alternatives to 18F-labelled deoxyglucose would appear to be promising.54 Invasive investigations such as selective arterial calcium (insulinoma) and secretin (gastrinoma) stimulation with hepatic/portal venous sampling are not used routinely and are only undertaken if there is a high suspicion, but non-invasive imaging has failed to localise the tumour.53,55

Treatment

Once the diagnosis of a functioning tumour is established, control of the hormonal excess is the first priority in minimising symptoms and complications. Medications used for each individual tumour are shown in Table 16.3. Somatostatin analogue infusions are recommended pre- and intraoperatively for carcinoid tumours to prevent carcinoid crisis.48 Surgery offers the only chance of cure for those with localised disease for PNETs. The approach is dependent on tumour type and the presence or absence of an inherited syndrome. The specific management of hereditary PNETs is beyond the remit of this chapter and readers are referred to more detailed reviews for an in-depth discussion.49,53,55

Over 80% of localised sporadic insulinomas are solitary, benign and under 2 cm in size, making them ideal for consideration of enucleation and laparoscopic resection.53 Enucleation is considered possible if the lesion can be clearly localised pre- or intraoperatively and if the relationship to the pancreatic duct has been clearly identified.48 Intraoperative ultrasound has been shown to be particularly valuable in helping to assess these factors.53 Postoperatively, histological conformation of the benign nature must be confirmed.48 Resection is required for tumours where malignancy is suspected (hard, infiltrating tumour, duct obstruction or lymph node involvement), if there is major vascular involvement or the tumour is large.53 Patients should be assessed for resection as for any pancreatic tumour. However, if a distal pancreatectomy is being performed attempts to preserve the spleen should be made.53 Blind pancreatic resection should be avoided.53 Not surprisingly given the rare nature of the tumour, data in support of laparoscopic resection remain limited to small case series; however, early results indicate that although it can be performed safely, significant conversion, re-exploration and morbidity rates remain.56

Duodenotomy and intraoperative ultrasound combined with palpation (sensitivity 91–95%) are the key to successful intraoperative localisation.55 For duodenal gastrinomas, small tumours (< 5 mm) can be enucleated from the submucosa while larger tumours require full-thickness excision.55 For pancreatic gastrinomas, intraoperative assessment regarding the suitability for enucleation (similar to that described above for insulinomas) should be performed. However, if the tumour is not suitable, a formal pancreatic resection (pancreatico-duodenectomy) should be performed. If enucleation is performed, consideration of peripancreatic nodal sampling should be undertaken, given the high rate of metastatic disease.58

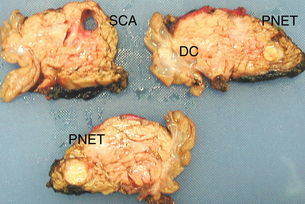

Most localised non-functioning tumours will be detected at such a size that enucleation is not feasible. Given the discrepancy between the clinical and autopsy incidence of PNETs and the increasing use of cross-sectional imaging, this is likely to become a more frequent possibility. The size at which patients with asymptomatic suspected benign, non-functioning PNETs should undergo resection is not clear.59 Although the risk of malignancy is related to size, tumours between 1 and 3 cm can harbour malignant potential59 (Fig. 16.4). Currently, patients should be assessed regarding fitness for surgery and an informed decision made with the patient regarding resection or observation. Central pancreatectomy has also been shown to be feasible for selected tumours and has the advantage of reducing the risk of postoperative diabetes.36 A formal resection with lymphadenectomy should be performed for suspected malignant tumours as lymph node metastases are common (27–83%).59

Figure 16.4 A 30-year-old female with Von Hippel–Lindau disease underwent pancreatic screening. Radiological imaging revealed five neuroendocrine tumours within the pancreatic head. Pancreatico-duodenectomy was performed. Pathological sectioning of the pancreatic head revealed multiple neuroendocrine tumours (PNETs), including at least one well-differentiated pancreatic endocrine carcinoma (node positive) and a well-differentiated duodenal endocrine carcinoma (DC). All tumours were between 12 and 18 mm diameter. An incidental serous cyst adenoma (SCA) was also identified.

Resection is the treatment of choice for symptomatic patients with localised disease.59 The median survival for those who underwent resection was significantly longer than for those with metastatic disease or locally advanced unresectable disease (7.2 years vs. 2.1 and 5.2 years, respectively).59 Importantly, however, 48% of patients who underwent resection for localised disease developed recurrence at a median follow-up of 2.7 years.59 Because of the long natural history of these tumours and given that many are symptomatic and difficult to palliate without resection (e.g. tumour bleeding), the criteria for what determines unresectable disease may not be the same as those for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. The MD Anderson experience would suggest that, in high-volume centres, major venous reconstruction can be performed safely, but only rarely should arterial reconstruction (isolated hepatic artery involvement) or upper abdominal exenteration be performed, due to the associated high long-term morbidity.59 In addition, a recent report has also indicated that an incomplete resection (R2) is associated with a high perioperative mortality and may in fact be detrimental to the patient’s survival.60

Metastatic disease

Only 10% of patients with hepatic metastases will be suitable for potentially curative resection.48 However, it would appear that although recurrence rates are high, a survival advantage can be achieved, although randomised data are lacking.61 Synchronous cholecystectomy should be performed to reduce complications from adjuvant therapy such as somatostatin analogues and hepatic artery embolisation.61 For patients with non-functioning unresectable metastatic disease, there is no evidence to support palliative or ‘debulking’ resections, with possibly the only exceptions being those who have significant local symptoms from the primary and low-volume hepatic metastases.59 For those with obstruction of the gastrointestinal or biliary tract, surgical bypass should be the first-line treatment in those with well-differeniated disease, given the indolent nature of the disease.61

Until recently the role of chemotherapy for PNETs has been based around streptozocin and 5-fluorouracil after a randomised trial in 1979 showed a survival advantage for patients with metastatic carcinoid tumours receiving combination chemotherapy.62 However, given the side-effects and variable behaviour of PNETs, it has not been widely accepted into clinical practice.

Pathology and outcome

PNETs are classified into four groups based on a combination of clinical, histological and molecular features.48 Tumours confined to the pancreas are classified as well-differentiated endocrine tumours that can be subdivided into those of benign behaviour (< 2 cm size), < 2 mitoses per 10 high-power fields (HPFs), Ki67 index < 2% (and no vascular invasion) or uncertain behaviour (if the above criteria are not met). Tumours not confined to the pancreas (gross local invasion or metastases) or that exhibit evidence of small-cell carcinoma are considered endocrine carcinoma, which are further subdivided into well-differentiated (well to moderately differentiated, mitotic rate 2–10 per 10 HPFs, Ki67 index > 5%) or poorly differentiated (small-cell carcinoma, necrosis, > 10 mitoses per 10 HPFs, Ki67 index > 15%, prominent vascular and perineural invasion). Importantly, the diagnosis of functional tumours is not made histologically but clinically, as immunohistochemical staining of specific hormones does not correlate with the clinical picture.48 In 2010, the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) published its first TNM staging classification for PNETs.65 Using this, Strosberg et al. retrospectively applied the staging system to a dataset of 425 patients with PNETs.66 Five-year overall survival for stages I–IV was 92%, 84%, 81% and 57%, respectively, thus indicating the proposed system is a useful adjunct for classifying PNETs.

Other tumours

The other two main types of cystic neoplasms are serous (SCA) and mucinous (MCN) cystic neoplasms. Because of the difference in malignant potential, the management of these two tumours differs, yet clinically and radiologically there is considerable overlap. It is therefore useful to contrast and compare them. The exact incidence of serous and mucinous cystic tumours is unknown; however, in a retrospective review of 24 039 patients undergoing radiological imaging, 0.7% had pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Of the 49 (0.2%) who underwent surgery, 10 and 16 patients had a final diagnosis of SCA and MCN, respectively.67 SCAs are more common in men (2:1), with a peak incidence in the seventh decade, and evenly distributed throughout the pancreas, with up to a third being asymptomatic.68 In contrast, MCNs are predominantly found in women, with a peak incidence in the fifth decade, and are more likely to be located within the tail.69 SCAs are also commonly associated with Von Hippel–Lindau syndrome49 (Fig. 16.4), and young patients presenting with multiple cystic lesions involving the pancreas and kidneys should be genetically assessed.68

On cross-sectional imaging, the typical appearances of an SCA are of a microcystic (> 6 cysts, each cyst < 2 cm individual diameter) lesion with or without central calcification (so-called sunburst calcification).18,70 When the classic features are present, differentiation from other tumours is not difficult; however, a rare solid type exists that radiologically can be mistaken for neuroendocrine tumour.12 MRI may be useful in this setting.18 The presence of a uni- or oligolocular macrocystic (> 2 cm) lesion is more difficult to diagnose and a wide differential exists. Both SCAs (oligocystic type) and MCNs can fall into this group, although MCNs are less likely to be multilocular and, if calcification occurs, it does so peripherally and may be a marker of underlying malignancy.18 The presence of solid components within a cystic lesion indicates the presence of, or high risk of, malignancy and therefore surgical resection should be considered.18 Included within this differential would be PNET, solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (young women) or mucinous cyst adenocarcinoma.18 It is unusual for either SCAs or MCNs to communicate with the pancreatic duct, but it has been reported.18

The ability of non-interventional imaging to obtain an accurate diagnosis is limited. In a recent report of 100 SCAs from Bassi et al.,71 the correct diagnosis was achieved in 53%, 54% and 76% by ultrasound (US), CT and MRI, respectively. An incorrect diagnosis was made in 31%, 34% and 26%, and the investigation was non-diagnostic in 16%, 12% and 0% with US, CT and MRI, respectively.

In a study7 of solitary cystic (IPMNs were excluded) neoplasms, 71 patients underwent EUS and fluid aspiration (for mucin, viscosity, amylase, lipase, CEA, CA19-9, cytology) followed by surgery to assess its accuracy.72 The authors concluded that an accurate algorithm using measurement of viscosity, lipase and CEA can be used to determine the diagnosis of cystic lesions. A viscosity of ≥ 1.6 indicates an MCN and the patient should be offered resection. If it is < 1.6 and the lipase is < 6000 U/mL, this indicates an SCA. If the viscosity is < 1.6 and lipase is > 6000 U/mL, then a CEA measurement should be performed, and if this value is less than 480 U/mL the diagnosis is a pseudocyst. If it is > 480 U/mL, a repeat EUS and fine-needle aspiration should be performed in 3–6 months. Using this algorithm, only 2 of 71 patients that underwent resection for suspected MCN had a final histology revealing a pseudocyst.

Pathologically, SCAs demonstrate monomorphous cuboidal-shaped epithelium. The cells are glycogen rich with cellular cytoplasm and small regular nuclei. There is a lack of mitotic activity. The cysts appear ‘empty’ on microscopy. In contrast, the cyst content of MCNs is turbid and tenacious.68 Microscopically (unlike SCAs) the cyst lining can be highly variable. The cells are mucin producing, which can be a single cell layer of flattened cuboidal epithelium or contain papillary tufting.68 The tumours are classified as benign, borderline or malignant depending on the nuclear features of the cells.68 It is important to examine the whole tumour as malignant invasion can occur without the presence of a mass.68 The unique feature of MCNs, however, is the presence of ovarian stroma (highly cellular, densely packed, plump spindle cells). Current recommendations require the presence of this for a tumour to be classified as MCN.4 This is particularly important when the differential includes IPMN, in which this type of stroma is not seen.4

References

1. Winter, J.M., Cameron, J.L., Campbell, K.A., et al, 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: a single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg 2006; 10:1199–1210. 17114007

2. Ohashi, K., Murakami, Y., Maruyama, M., et al. Four cases of mucin producing cancer of the pancreas on specific findings of the papilla of Vater [in Japanese]. Prog Dig Endosc. 1982; 20:348–351.

3. Longnecker, D.S., Adler, G., Hruban, R.H., et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. In: Hamilton S.R., Aaltonen L.A., eds. World Health Organisation classification of tumours, pathology and genetics of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000:237–241.

4. Tanaka, M., Cahri, S., Adsay, V., et al, International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology 2006; 6:17–32. 16327281

5. Reid-Lombardo, K.M., St Sauver, J., Li, Z., et al, Incidence, prevalence, and management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1984–2005: a population study. Pancreas 2008; 37:139–144. 18665073

6. Riall, T.S., Stager, V.M., Nealon, W.H., Incidence of additional primary cancers in patients with invasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and sporadic pancreatic adenocarcinomas. J Am Coll Surg 2007; 204:803–813. 17481488

7. Macari, M., Eubig, J., Robinson, E., et al, Frequency of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm in patients with and without pancreas cancer. Pancreatology 2010; 10:734–741. 21252588

8. Sohn, T.A., Yeo, C.A., Cameron, J.L., et al, Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an increasingly recognized clinicopathologic entity. Ann Surg 2001; 234:313–321. 11524584

9. Sohn, T.A., Yeo, C.A., Cameron, J.L., et al, Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an updated experience. Ann Surg 2004; 239:788–797. 15166958

10. Fujino, Y., Matsumoto, I., Ueda, T., et al, Proposed new score predicting malignancy of IPMN of the pancreas. Am J Surg 2007; 194:304–307. 17693271

11. Winter, J.M., Cameron, J.L., Lillemoe, K.D., et al, Periampullary and pancreatic incidentaloma: a single institution’s experience with an increasingly common diagnosis. Ann Surg 2006; 243:673–680. 16633003

12. Irie, H., Yoshimutu, K., Tajima, T., et al, Imaging spectrum of cystic pancreatic lesions: learn from atypical cases. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2007; 36:213–226. 17765800

13. Yamada, Y., Mori, H., Matsumoto, S., Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: correlation of helical CT and dynamic MR imaging features with pathologic findings. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33(4):474–481. 17680299

14. Pilleul, F., Rochette, A., Partensky, C., et al, Preoperative evaluation of intraductal papillary mucinous tumors performed by pancreatic magnetic resonance imaging and correlated with surgical and histopathologic findings. J Magn Reson Imaging 2005; 21:237–244. 15723374

15. Kawamoto, S., Lawler, L.P., Horton, K.M., et al, MDCT of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: evaluation of features predictive of invasive carcinoma. Am J Roentgenol 2006; 186:687–695. 16498096

16. Kang, M.J., Jang, J.Y., Kim, S.J., et al, Cyst growth rate predicts malignancy in patients with branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9:87–93. 20851216

17. Tomimaru, Y., Takeda, Y., Tatsumi, M., et al, Utility of 2-[18F] fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography in differential diagnosis of benign and malignant intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Oncol Rep 2010; 24:613–620. 20664965

18. García Figuerias, R., Villalba Martín, C., García Figuerias, A., et al, The spectrum of cystic masses of the pancreas. Imaging features and diagnostic difficulties. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2007; 36:199–212. 17765799

19. Procacacci, C., Carbognin, G., Biasiutti, C., et al, Intraductal papillary mucinous tumours of the pancreas: spectrum of CT and MR findings with pathologic correlation. Eur Radiol 2001; 11:1939–1951. 11702126

20. Cone, M.M., Rea, J.D., Diggs, B.S., et al, Endoscopic ultrasound may be unnecessary in the preoperative evaluation of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. HPB (Oxford) 2011; 13:112–116. 21241428

21. Kubo, H., Chijiiwa, Y., Akahoshi, K., et al, Intraductal papillary-mucinous tumors of the pancreas: differential diagnosis between benign and malignant tumors by endoscopic ultrasonography. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96:1429–1434. 11374678

22. Pais, S.A., Attasaranya, S., Leblanc, J.K., et al, Role of endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: correlation with surgical histopathology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 5:489–495. 17350894

23. Michaels, P.J., Brachtel, E.F., Bounds, B.C., et al, Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: cytologic features predict histologic grade. Cancer 2006; 108:163–173. 16550572

24. Tanaka, M., Kobayashi, K., Mizumoto, K., et al, Clinical aspects of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. J Gastroenterol 2005; 40:669–675. 16082582

25. Hwang, D.W., Jang, J.Y., Lim, C.S., et al, Determination of invasive predictors in branch duct type IPMN of the pancreas: a suggested scoring formula. J Korean Med Sci 2011; 26:740–748. 21655058

26. Maimone, S., Agrawal, D., Pollack, M.J., et al, Variability in measurements of pancreatic cyst size among EUS, CT and MRI modalities. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 71:945–950. 20231021

27. Hruban R.H., Pitman M.B., Klimstra D.S., eds. AFIP atlas of tumor pathology. Tumors of the pancreas. Washington, DC: ARP Press, 2007.

28. Ban, S., Naitoh, Y., Mino-Kenudson, M., et al, IPMN of the pancreas: its histopathological difference in 2 types. Am J Surg Pathol 2006; 30:1561–1569. 17122512

29. Furukawa, T., Hatori, T., Fujita, I., et al, Prognostic relevance of morphological types of IPMN of the pancreas. Gut 2011; 60:509–516. 21193453

30. Sugiyama, M., Izumisato, Y., Abe, N., et al, Predicitive factors for malignancy in IPMN of the pancreas. Br J Surg 2003; 90:1244–1249. 14515294

31. Nagai, K., Doi, R., Kida, A., et al, Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: clinicopathological characteristics and long term follow up after resection. World J Surg 2008; 32:271–278. 18027021

32. Rodriguez, J.R., Salvia, R., Crippa, S., et al, Branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: observations in 145 patients who underwent resection. Gastroenterology 2007; 133:72–79. 17631133

33. Salvia, R., Crippa, S., Falconi, M., et al, Branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: to operate or not to operate? Gut 2007; 56:1086–1090. 17127707

34. Bae, S.Y., Lee, K.T., Lee, J.H., et al, Proper management and follow-up stratergy of branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(3):257–260. 22030480

35. Fujino, Y., Suzuki, Y., Yoshikawa, T., et al, Outcomes of surgery for IPMN of the pancreas. World J Surg 2006; 30:1909–1914. 16850142

36. Crippa, S., Bassi, C., Warshaw, A.L., et al, Middle pancreatectomy: indications, short- and long-term operative outcomes. Ann Surg 2007; 246:69–76. 17592293

37. Wada, K., Kozarek, R.A., Traverso, L.W., Outcomes following resection of invasive and non invasive IPMN of the pancreas. Am J Surg 2005; 189:632–635. 15862510

38. Hardacre, J.M., McGee, M.F., Stellato, T.A., et al, An aggressive surgical approach is warranted in the management of cystic pancreatic neoplasms. Am J Surg 2007; 193:374–379. 17320538

39. Turrini, O., Waters, J.A., Schnelldorfer, T., et al, Invasive IPMN: predictors of survival and role of adjuvant therapy. HPB (Oxford) 2010; 12:447–455. 20815853

40. Kargozaran, H., Vu, V., Ray, P., et al, Invasive IPMN and MCN: same organ, different outcome. Ann Surg Oncol 2011; 18:345–351. 20809175

41. Yopp, A.C., Katabi, N., Janakos, M., et al, Invasive carcinoma arising in IPMN of the pancreas. A matched control study with conventional pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2011; 253:968–974. 21422912

42. D’Angelica, M., Brennan MF, Suriawinata AA, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. An analysis of clinicopathological features and outcome. Ann Surg 2004; 239:400–408. 15075659

43. White, R., D’Angelica, M., Katabi, N., et al, Fate of the remnant pancreas after resection of non-invasive IPMN. J Am Coll Surg 2007; 204:987–995. 17481526

44. Park, J., Lee, K.T., Jang, T.H., Risk factors associated with post operative recurrence of IPMN of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2011;40(1):46–51. 21160369

45. Tomimaru, Y., Ishikawa, O., Ohigashi, H., et al, Advantage of pancreaticogastrostomy in detecting recurrent intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma in the remnant pancreas: a case of successful re-resection after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Surg Oncol 2006; 93:511–515. 16615155

46. Kimura, W., Kurda, A., Morioka, Y., Clinical pathology of endocrine tumours of the pancreas: analysis of autopsy cases. Dig Dis Sci 2004; 36:933–942. 2070707

47. Bilimoria, K.Y., Tomlinson, J.S., Merkow, R.P., et al, Clinicopathologic features and treatment trends of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: analysis of 9,821 patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2007; 11:1460–1467. 17846854

48. Ramage, J.K., Davies, A.H.G., Ardill, J., et al, Guidelines for the management of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Gut 2005; 54:1–16. 15591495

49. Alexakis, N., Connor, S., Ghaneh, P., et al, Hereditary pancreatic endocrine tumours. Pancreatology 2004; 4:417–433. 15249710

50. Lawrence, B., Gustafsson, B.L., Kidd, M., et al, The clinical relevance of chromogranin A as a biomarker for gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40(1):111–134. 21349414

51. Rha, S.E., Jung, S.E., Lee, K.H., et al, CT and MR imaging of endocrine tumour of the pancreas according to WHO classification. Eur J Radiol 2007; 62:371–377. 17433598

52. Rockall, A.G., Reznek, R.H., Imaging of neuroendocrine tumours. Best Pract Clin Endocr Metab 2007; 21:43–68. 17382265

53. Tucker, O.N., Crotty, P.L., Conlon, K.C., The management of insulinoma. Br J Surg 2006; 93:264–275. 16498592

54. Sundin, A., Garske, U., Orlefors, H., Nuclear imaging of neuroendocrine tumours. Best Pract Clin Endocr Metab 2007; 21:69–85. 17382266

55. Fendrich, V., Langer, P., Waldmann, J., et al, Management of sporadic and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 gastrinomas. Br J Surg 2007; 94:1331–1341. 17939142

56. Mabrut, J.Y., Fernandez-Cruz, L., Azagra, J.S., et al, Laparoscopic pancreatic resection; results of a multi-centre European study of 127 patients. Surgery 2005; 137:597–605. 15962401

57. Norton, J.A., Fraker, D.L., Alexander, H.R., et al, Surgery increases survival in patients with gastrinoma. Ann Surg 2006; 244:410–419. 16926567 In a study of 160 patients with gastrinomas, 35 patients (with similar staged localised disease) who did not undergo resection were compared to those who underwent resection. After 12 years’ follow-up, 29% of those who did not undergo surgery had developed hepatic metastases compared to 5% in the resected group (P < 0.001).

58. Akerstrom, G., Hellman, P., Surgery on neuroendocrine tumours. Best Pract Clin Endocr Metab 2007; 21:87–109. 17382267

59. Kouvaraki, M.A., Solorzano, C.C., Shapiro, S.E., et al, Surgical treatment of non functioning pancreatic islet cell tumours. J Surg Oncol 2005; 89:170–185. 15719379

60. Bloomston, M., Muscarella, P., Shah, M.H., et al, Cytoreduction results in high perioperative mortality and decreased survival in patients undergoing pancreatectomy for neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg 2006; 10:1361–1370. 17175455

61. Minter, R.M., Simeone, D.M., Contemporary management of nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16(2):435–446. 22009463

62. Moertel, C.G., Hanley, J.A., Combination chemotherapy trials in metastatic carcinoid tumor and the malignant carcinoid syndrome. Cancer Clin Trials 1979; 2:327–334. 93982

63. Raymond, E., Dahan, L., Raoul, J.L., et al, Sunitinib malate for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:501–513. 21306237 One hundred and seventy-one patients with advanced and progressive PNETs were randomised in double-blind fashion to placebo or sunitinib. The trial was stopped early due to increased complications and death in the placebo group. An improved progression-free survival (11.5 vs. 5.5 months, P < 0.001) and reduced risk of death (105 vs. 255, P = 0.02) were seen in the treatment group.

64. Yao, J.C., Shah, M.H., Ito, T., et al, Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:514–523. 21306238 In a placebo-controlled randomised crossover design trial, 410 patients with advanced and progressive PNETs were enrolled to placebo or everolimus. In those patients who received everolimus there was a 65% reduction in risk of progression (median progression-free survival was 11 months vs. 4.6 months) as compared to placebo. In addition, tolerance was high.

65. Edge S.B., Byrd D.R., Compton C.C., et al, eds. AJCC cancer staging manual, 7th ed., Chicago, IL: Springer, 2010.

66. Strosberg, J.R., Cheema, A., Weber, J., et al, Prognostic validity of a novel American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Classification for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. PNETs. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29:3044–3049. 21709192

67. Spinelli, K.S., Fromwiller, T.E., Daniel, R.A., et al, Cystic pancreatic neoplasms: observe or operate. Ann Surg 2004; 239:651–659. 15082969

68. Compton, C.C., Histology of cystic tumours of the pancreas. Gastroint Endosc Clin North Am 2002; 12:673–696. 12607779

69. Sarr, M.G., Kendrick, M.L., Nagorney, D.M., et al, Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Surg Clin North Am 2001; 81:497–509. 11459267

70. Megibow, A.J., Lavelle, M.T., Rofsky, N.M., Cystic tumors of the pancreas. The radiologist. Surg Clin North Am 2001; 81:489–495. 11459266

71. Bassi, C., Salvia, R., Molinari, E., et al, Management of 100 consecutive cases of pancreatic serous cystadenoma: wait for symptoms and see at imaging or vice versa? World J Surg 2003; 27:319–323. 12607059

72. Linder, J.D., Geenen, J.E., Catalano, M.F., Cyst fluid analysis obtained by EUS-guided FNA in the evaluation of discrete cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: a single centre experience. Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 64:697–702. 17055859