Cyanosis

Perspective

Pathophysiology

Cyanosis is evident on physical examination when the absolute amount of desaturated (unoxygenated) hemoglobin in the circulating capillary blood is elevated to approximately 5 g/dL.1,2 It is not a percent of desaturated total hemoglobin mass or a decreased amount of oxyhemoglobin. For this reason, patients with a relatively low hemoglobin level exhibit cyanosis at a much lower partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) and arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) than those with normal hemoglobin levels. Cyanosis is an insensitive indicator of tissue oxygenation.3 Its presence suggests hypoxia, buts its absence does not exclude it.

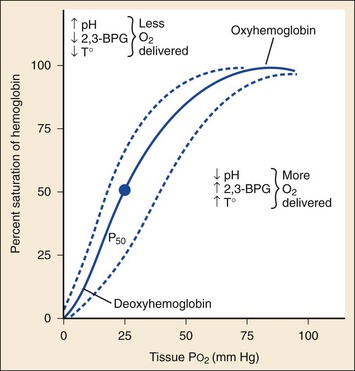

Abnormal hemoglobin forms contribute significantly to cyanotic disease. Under normal conditions, red blood cells (RBCs) contain hemoglobin with iron in the reduced ferrous state (Fe2+). The iron molecule may be oxidized to the ferric state (Fe3+) to produce methemoglobin. This reaction impairs the ability of hemoglobin to transport oxygen to and carbon dioxide from the tissues. The oxygen dissociation curve is shifted to the left, resulting in tissue hypoxia and lactic acid production (Fig. 14-1). Methemoglobin normally accounts for less than 1% of total hemoglobin.4 Cyanosis results when greater than 10 to 25% of the total hemoglobin is methemoglobin (approximately 1.5 g/dL), which has a dark purple-brown or chocolate brown color even when exposed to room air. Methemoglobin is reduced to ferrous hemoglobin primarily by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) cytochrome-b5 reductase, an enzyme system present within RBCs. A secondary system dependent on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-reductase uses glutathione production and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) to reduce methemoglobin to hemoglobin. This secondary pathway normally plays a minor role but is accelerated by methylene blue.4

Primary methemoglobinemia is the result of a congenital error in enzyme metabolism, with either diminished levels of NADH reductase or an abnormally functioning enzyme. Patients may have cyanosis in a stable compensated state. Acquired methemoglobinemia occurs when methemoglobin production (hemoglobin oxidation) is accelerated beyond the capacity of NADH reductase activity. This usually occurs as a drug reaction. (See Box 14-1 for common causes.) Newborns are at risk for methemoglobinemia because their NADH reductase activity is relatively low.5

Diagnostic Approach

Differential considerations for patients with cyanosis are listed in Box 14-2.

Pivotal Findings

The onset, duration, and time of day of symptoms and any previous episodes should be noted. Precipitating factors may include exposure to cold air or water, high altitude, or exercise in patients with a history of cardiopulmonary disease. Additional history should include known congenital heart disease or cardiopulmonary disease, hypercoagulable states, and any family history of cyanotic disease or hematologic illness. A history of home or occupational exposures to fumes or chemicals should be obtained, including aniline, azo dyes (phenazopyridine [Pyridium]), phenacetin, and nitrates.6 A drug history should be reviewed, including use of prescription and over-the-counter medications, health food supplements, and herbal or alternative preparations.7 The potential of pseudocyanosis resulting from exposure to dyes, heavy metals, or topically absorbed pigments should be explored.8

In infants, congenital heart disease is suggested by difficulty feeding, sweating, lethargy, poor weight gain, or respiratory distress. Episodic cyanotic events, or “tet spells,” may be seen in children with tetralogy of Fallot (ventricular septal defect, overriding aorta, pulmonic stenosis or atresia, and right ventricular hypertrophy with outlet obstruction). These patients have cyanosis, tachypnea, and anxiety owing to decreased pulmonary blood flow with shunting of unoxygenated blood into the peripheral circulation.9,10

Signs

There is significant interobserver variability in detecting cyanosis on physical examination. Room lighting and temperature may affect examination of the skin and mucous membranes. A patient’s natural skin tone, thickness, and pigmentation also may alter findings.3

Vital signs should be obtained from all patients. Temperature is typically normal. Blood pressure and heart rate vary unpredictably. Upper airway obstruction and other signs of respiratory insufficiency should be sought. Intermittent apnea in infants suggests central nervous system immaturity or a central lesion. Infants with cyanosis, increased respiratory depth, periodic apnea episodes, or diaphoresis with feeding may have congenital heart disease.9,10 Tachypnea (>60 breaths/min) in a newborn may indicate a pulmonary disorder, congenital heart disease, infection, metabolic disorder, or gastrointestinal or central nervous system pathology.11

General appearance and mental status should be evaluated. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat examination may reveal central cyanosis. Funduscopic examination may detect dilated tortuous veins and papilledema in patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease.12 Jugular venous distention may be seen on the neck examination in patients with pulmonary edema.

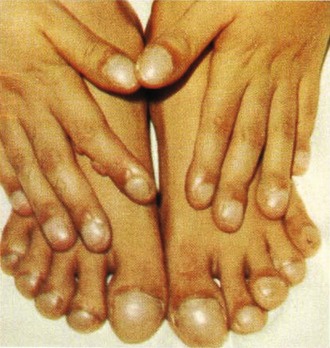

Extremity examination includes evaluation of nail beds for peripheral cyanosis, strength and symmetry of distal pulses, and capillary refill. Evidence of chronic vascular disease, such as hair loss and temperature difference, should be noted. Clubbing of the nails may occur because of increased soft tissue and expansion of the capillary beds (Fig. 14-2). Clubbing may be idiopathic or hereditary but is usually the result of chronic hypoxemic states, such as cyanotic heart disease, infective endocarditis, pulmonary disease (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis), and some gastrointestinal disorders (cirrhosis, Crohn’s disease, and regional enteritis). Thrombotic events should also be considered with findings of skin and nail bed hemorrhages or end-organ damage (eye, kidney).

Laboratory and Ancillary Testing

The complete blood count should be checked to assess for erythrocytosis, polycythemia, or anemia.13 Peripheral smear assesses RBC morphology and fragments, as well as white blood cell differential count. A D-dimer level may be obtained if pulmonary embolism (PE) is suspected. A normal D-dimer is useful in ruling out PE in patients with a low pretest probability for the disease.14

The peripheral blood classically appears chocolate brown in color. Normally a small drop of blood placed on a white sheet or filter paper will turn bright red in color when exposed to 100% oxygen. No change in color is highly suggestive of methemoglobinemia.4

Interpretation of pulse oximetry is problematic in the setting of cyanosis (see Chapter 5). Assessment of distal perfusion usually determines if poor circulation is a cause of low pulse oximetry. Pulse oximetry measures light absorbance of tissue at 660 nm (red, reduced hemoglobin) and 940 nm (infrared, oxyhemoglobin). The ratio of these two readings is the basis of the pulse oximetry calculation. Methemoglobin absorbs well at both wavelengths, resulting in a saturation approximation of 85%, regardless of the actual PaO2 and SaO2.15,16

Arterial blood gas testing assesses SaO2, often sampled when the patient is breathing room air (see Fig. 14-1). CO-oximetry measurements should be specifically ordered if carbon monoxide exposure or methemoglobinemia is suspected. Sulfhemoglobin is reported as methemoglobin on CO-oximetry, so if sulfhemoglobinemia is possible, measured oxygen saturation should be specifically requested. Newer devices designed to measure methemoglobin levels noninvasively (pulse CO-oximetry) may be useful but have decreasing accuracy at lower SaO2 levels (<95%) and higher methemoglobin levels (>14%).17,18

Differential Algorithms

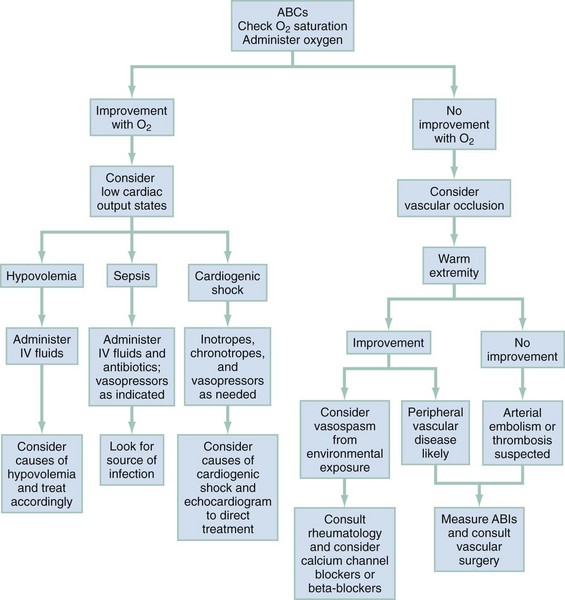

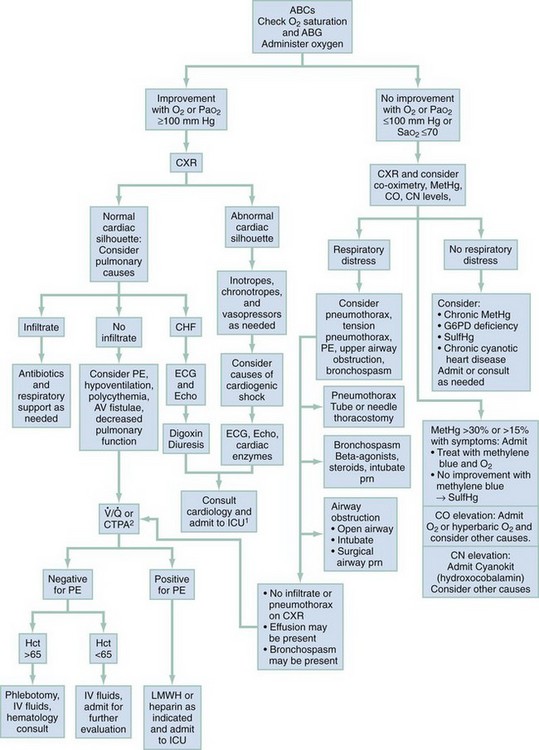

Figures 14-3 and 14-4 outline an approach to the differential diagnosis and treatment for peripheral and central cyanosis, respectively. During the initial assessment, as the distribution of cyanosis is noted, the clinician should initiate oxygen therapy and follow steps to determine the cause of cyanosis. Clinical improvement with oxygen suggests diffusion impairment. Patients who do not respond to high-concentration oxygen are more likely to have ventilation-perfusion ratio abnormalities, such as shunting from a consolidated pulmonary lobule or congenital heart disease with right-to-left shunting. Cardiac size and silhouette on a chest radiograph may provide a clue to the presence of congenital cardiac disease. If heart size is normal, impaired pulmonary function, pulmonary embolus, or other noncardiac causes should be considered. If no improvement occurs with 100% oxygen therapy, the patient’s respiratory status should be reassessed, and tension pneumothorax or upper airway obstruction considered. Pulmonary embolus should be considered and a computed tomography pulmonary angiogram performed. If a patient exhibits no respiratory distress and remains resistant to oxygen therapy, cardiac shunting or abnormal hemoglobin forms should be considered and treated accordingly. Superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome should be suspected in patients with central cyanosis with facial, neck, and upper extremity swelling with venous distention and plethora.19

Figure 14-4 An algorithmic approach to central cyanosis. ABCs, airway, breathing, circulation; ABG, arterial blood gas; AV, arteriovenous; CHF, congestive heart failure; CN, cyanide; CO, carbon monoxide; CTPA, computed tomography pulmonary angiography; CXR, chest radiograph; ECG, electrocardiogram; Echo, echocardiogram; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; Hct, hematocrit; ICU, intensive care unit; IV, intravenous; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; MetHgb, methemoglobin; O2, molecular oxygen; PaO2, partial pressure of arterial oxygen; PE, pulmonary embolus; prn, as needed; RA, room air; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation; SulfHg, sulfhemoglobin;  , ventilation-perfusion scan.

, ventilation-perfusion scan.

1Patients with chronic cyanotic heart disease may not require ICU care or even hospital admission. Disposition should be discussed with patient’s cardiologist.

2 may be performed when CTPA is unavailable or contraindicated.

may be performed when CTPA is unavailable or contraindicated.

Emergent Diagnoses

Sulfhemoglobinemia is a rare cause of cyanosis most commonly occurring after exposure to hydrogen sulfide from organic sources, medications that are sulfonamide derivatives, or gastrointestinal sources (bacterial overgrowth).20 Strong consideration should be given to sulfhemoglobin toxicity in patients with cyanotic findings and methemoglobin on CO-oximetry but who do not improve with methylene blue treatment.

Finally, vascular disease, such as Raynaud’s phenomenon, may cause a cyanotic appearance. Raynaud’s phenomenon occurs in 15% of the population and has a female predominance. Patients have an abnormal response to excessive cold or emotional stress and report vasoconstriction, profound cold sensitivity, and recurrent events of sharply demarcated pallor or cyanosis of the digits. Most commonly the cutaneous arterial capillary beds of the fingers and toes are affected,21 but tongue, ear, and other distal areas may also be affected.

Empirical Management

Specific Strategies

Other Causes of Cyanosis

Acute therapy for patients with symptomatic hyperviscosity syndrome and secondary polycythemia includes phlebotomy and volume expansion with isotonic crystalloid. The goal of therapy is a normal hematocrit (45%).22 Long-term therapy is focused on the underlying cause, and patients require referral to a hematologist.

Patients with SVC syndrome require further evaluation for mediastinal mass or vascular abnormality. Conservative management with oxygen and elevation of the head of the bed often provide significant symptomatic relief. Vascular stenting may be necessary, and radiation or chemotherapy may be indicated in cases caused by malignancy.19

Raynaud’s phenomenon is treated by warming the affected digits and extremities. Systemic vasodilating agents (e.g., calcium channel blockers [nifedipine] or nitrates, endothelin antagonists, statins, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, and botulinum toxin) may be useful in the acute setting.21 If there is no improvement of peripheral cyanosis with warming and administration of 100% oxygen, arterial insufficiency or occlusion may be present. In cases of critical limb ischemia, intravenous heparin should be considered in consultation with a vascular surgeon. Embolic sources, such as endocarditis and abdominal aortic aneurysms, should be considered. Vascular bypass, intra-arterial thrombolysis, or stenting may be indicated.

Carbon monoxide and cyanide poisoning do not typically cause cyanosis and are covered elsewhere.

References

1. Da Silva, SS, Sajan, IS, Underwood, JP, 3rd. Congenital methemoglobinemia: A rare cause of cyanosis in the newborn—a case report. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e158.

2. Martin, L, Khalil, H. How much reduced hemoglobin is necessary to generate central cyanosis? Chest. 1990;97:182–185.

3. Comroe, JH, Botelho, S. The unreliability of cyanosis in the recognition of arterial anoxemia. Am J Med Sci. 1947;214:1–6.

4. El-Husseini, A, Azarov, N. Is threshold for treatment of methemoglobinemia the same for all? A case report and literature review. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:748e5–748e10.

5. Lin, CY, et al. Anesthetic management of a patient with congenital methemoglobinemia. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2009;47:143–146.

6. Bradberry, SM. Occupational methemoglobinemia: Mechanisms of production, features, diagnosis and management including the use of methylene blue. Toxicol Rev. 2003;22:13.

7. Chan, B, et al. Methemoglobinemia after ingestion of Chinese herbal medicine in a 9-day-old infant. Clin Toxicol. 2007;45:281.

8. Zillich, AJ, Kuhn, RJ, Petersen, TJ. Skin discoloration with blue food coloring. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:868–870.

9. Rao, PS. Diagnosis and management of cyanotic congenital heart disease: Part I. Indian J Pediatr. 2009;76:57–70.

10. Rao, PS. Diagnosis and management of cyanotic congenital heart disease: Part II. Indian J Pediatr. 2009;76:297–308.

11. Brousseau, T, Sharieff, GQ. Newborn emergencies: The first 30 days of life. Pediatric Clin North Am. 2006;53:69–84.

12. Goel, N, Kumar, V, Seth, A, Ghosh, B. Proliferative retinopathy in a child with congenital cyanotic heart disease. J AAPOS. 2010;14:455–456.

13. Shelonitda, SR, Shah, AA, Hoover, DR, Saidi, P. Cyanotic congenital heart disease (CCHD) with symptomatic erythrocytosis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1775–1777.

14. Fesmire, FM, et al. Critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:628–652.

15. Zijlstra, WG, Buursma, A, Meeuwsen-van der Roest, WP. Absorption spectra of human fetal and adult oxyhemoglobin, de-oxyhemoglobin, carboxyhemoglobin, and methemoglobin. Clin Chem. 1991;37:1633–1638.

16. Haymond, S, Cariappa, R, Eby, CS, Scott, MG. Laboratory assessment of oxygenation in methemoglobinemia. Clin Chem. 2005;51:434–444.

17. Feiner, JR, Bickler, PE. Improved accuracy of methemoglobin detection by pulse co-oximetry during hypoxia. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:1160–1167.

18. Feiner, JR, Bickler, PE, Mannheimer, PD. Accuracy of methemoglobin detection by pulse co-oximetry during hypoxia. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:143–148.

19. Kogon, BE, et al. Cyanosis produced by superior vena caval stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:1083–1085.

20. Harangi, M, et al. Identification of sulfhemoglobinemia after surgical polypectomy. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2007;45:189–192.

21. Levien, TL. Advances in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2010;6:167–177.

22. Ruggeri, M, Finotto, S, Fortuna, S, Rodeghiero, F. Treatment outcome in a cohort of young patients with polycythemia vera. Intern Emerg Med. 2010;5:411–413.