Chapter 40 Cutaneous signs of nutritional disturbances

1. When do skin abnormalities occur in association with nutritional disturbances?

Skin manifestations occur when structural or enzymatic processes are affected by a deficiency or excess of a particular nutrient. This can be seen with dietary insufficiency or excess, malabsorption, drug interference, catabolic states, and metabolic, renal, hepatic, and inherited disorders. Nutrients include protein, carbohydrate, fat, vitamins, minerals, and trace elements.

2. Do nutritional disturbances involve the skin exclusively?

Absolutely not. Nutritional disorders are generalized conditions that cause multisystem disorders. Inadequate diet usually causes multiple nutrient deficiencies, with the resulting clinical picture a combination of these deficiencies. Clinical history, review of systems, and physical examination are of utmost importance when attempting to determine the underlying etiology of skin findings suggestive of a nutritional disorder.

3. Which skin changes are seen with protein and calorie deprivation in adults?

In clinical observations and prospective experiments, adults with starvation demonstrate rough, inelastic, pallid, gray skin with pigmentary changes in the malar and periorificial areas. Hair is thinned and growth of nails is slow. Nails may also demonstrate fissuring. There is decreased subcutaneous fat and, with time, muscle wasting.

4. What is marasmus?

Marasmus (from the Greek meaning wasting), or childhood caloric malnutrition, is a combined or proportional energy and protein deficiency with resultant catabolism and utilization of muscle and fat. There are no specific or significant skin findings. Infants often demonstrate a “monkey facies” due to loss of buccal fat that normally gives the face a rounded appearance.

Oumeish OY, Oumiesh I: Nutritional skin problems in children, Clin Dermatol 21:260–263, 2003.

5. What is kwashiorkor?

Kwashiorkor (from the Ga language of Ghana, meaning “sickness of the weanling”), or childhood protein malnutrition, is a result of protein deficiency with concurrent normal to excessive carbohydrate intake. It is a common affliction worldwide, and is seen in developed countries in association with poverty, neurologic disease, and malabsorption. There is muscle wasting with preservation of normal fat stores. The low ratio of protein to energy is felt to disrupt the body’s usual hypometabolic response to caloric deficiency and is biochemically manifest as markedly increased lipid peroxidation. Clinically, edema, hypoalbuminemia, growth retardation, fatty liver, psychomotor changes, and prominent skin findings are seen.

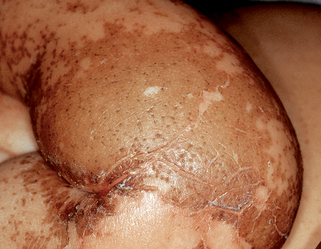

6. Describe the skin findings in kwashiorkor.

In black children, initial circumoral pallor progresses to diffuse depigmentation. In white children, there is diffuse blanching erythema that rapidly progresses to dusky nonblanching purple macules and papules. Classic findings include mosaic skin (dry, fine areas of desquamation with cracking along skin lines) and enamel paint dermatosis (Fig. 40-1), which evolves into large areas of erosion and desquamation. Hair in affected patients is sparse, thin, fragile, and depigmented. This hair depigmentation may produce the flag sign, which is alternating pigmented and depigmented bands seen along the hair shafts corresponding to periods of normal and inadequate nutrition.

8. Do skin abnormalities occur with fat deficiency?

Essential fatty acid deficiency occurs with deficiency of linoleic acid, a precursor of arachidonic acid. It is seen primarily with malabsorption syndromes and with prolonged total parenteral nutrition. Skin findings consist of a periorificial or generalized dermatitis caused by increased transepidermal water loss due to loss of the barrier function of the skin. Periorificial dermatitis cannot be clinically differentiated from lesions seen in acrodermatitis enteropathica (see question 18). Dietary or intravenous linoleic acid supplementation is curative, although adults often respond to only topical application.

9. Are any skin findings associated with fat excess?

Yes. Obesity researchers have documented an increased incidence of plantar hyperkeratosis (thickened soles), acanthosis nigricans, striae, and skin tags in patients overweight by more than 100%. Excess fat deposition predisposes to intertrigo, a dermatitis occurring between skinfolds, sometimes associated with secondary bacterial or candidal infection.

10. Which water-soluble vitamin abnormalities have skin findings?

Nearly all of the water-soluble vitamins demonstrate skin findings in deficiency states. There is considerable overlap in the skin findings, especially among the B-complex deficiencies, which is expected because they all function as coenzymes or cofactors in redox, carboxylation, or transamination reactions. Common clinical findings in riboflavin (B2), pyridoxine (B6), cobalamin (B12), and biotin deficiencies include angular cheilitis, periorificial dermatitis, and glossitis.

11. What is beriberi?

Beriberi is the name applied to severe vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency. Vitamin B1 deficiency is most commonly seen in alcoholism, imbalanced diets (e.g., polished rice diet), gastrointestinal disease, gastrointestinal surgery (e.g., gastric bypass surgery for obesity), and pregnancy. The mucocutaneous manifestations consist of limb edema and glossitis. The most important extracutaneous manifestations include mental confusion, peripheral neuropathies, confabulation, Wernicke encephalopathy, and congestive heart failure.

12. Name the four “Ds” of pellagra.

Pellagra (Italian, pelle-, meaning skin, and agra-, meaning sharp, burning, or rough) is a deficiency of niacin that manifests classically as the “four Ds.” Great variability is seen in the extent and type of gastrointestinal, neurologic, and skin manifestations. Niacin is available in animal products, enriched wheat flour, and is synthesized from tryptophan. Pellagra is most commonly seen in alcoholics and in patients on isoniazid therapy, which interferes with tryptophan metabolism.

13. Describe the dermatitis in pellagra.

The dermatitis is characteristically, but not invariably, photodistributed. Acutely, it is erythematous and may be associated with either pruritus or burning. Within 2 to 3 weeks, it becomes dry, scaly, and thickened. Casal’s necklace is a term used to describe sharply demarcated dermatitic lesions that develop around the neck and clinically resemble a necklace (Fig. 40-2). Dermatitic lesions also occur in the perineal and genital areas, over bony prominences, and on the face. The skin abnormalities in pellagra respond rapidly to niacin supplementation and heal in a centrifugal fashion.

14. Does scurvy still exist?

Yes, but it is rare. Vitamin C present in fresh fruits and vegetables is a necessary cofactor in collagen synthesis. Deficiency states initially demonstrate enlargement and keratosis of hair follicles with development of corkscrew hairs in adults. Within weeks, there is a proliferation of blood vessels around hair follicles (Fig. 40-3) and in the interdental papillae of gingiva with hemorrhage. Impaired collagen synthesis results in poor wound healing. Recent reports also describe clinical findings of purpura mimicking vasculitis and extensive ecchymoses on the lower extremities. Infantile scurvy is often associated with lower extremity fractures and subperiosteal hemorrhage and demonstrates a characteristic radiographic ground-glass osteopenia. It occurs most commonly between six and twenty four months and is associated with dietary deficiency of medical, social or economic cause.

15. Do deficiencies of the fat-soluble vitamins occur?

Yes, but less commonly because these vitamins have significant storage depots. Vitamin K deficiency is seen with malabsorption syndromes and in the newborn period prior to bacterial colonization of the intestine. Clinical lesions range from petechiae to massive hemorrhages. Vitamin D and E deficiencies are not associated with skin findings.

16. What abnormalities occur with vitamin A deficiency?

This disorder primarily involves the skin and eyes. Phrynoderma, the name applied to the cutaneous eruption of vitamin A deficiency, is a keratotic follicular eruption that initially appears on the proximal extremities. It eventually extends to the trunk, back, abdomen, buttocks, and neck. Although phrynoderma is widely accepted as being specific for vitamin A deficiency, it has recently been suggested that it may be a manifestation of severe malnutrition associated with deficiencies of multiple critical vitamins and essential fatty acids. Facial lesions may resemble large comedones of acne. Eye symptoms include nyctalopia (delayed dark adaptation, the earliest finding), night blindness, and xerophthalmia. Objective findings are Bitot’s spots, which are areas of shed corneal epithelium, and in severe disease, keratomalacia. Vitamin A deficiency is most commonly caused by malabsorption disorders.

17. Is vitamin A excess toxic?

Yes. Hypervitaminosis A may develop either acutely or chronically. Acute toxicity is rare but is most commonly due to vitamin A overdose. It has also been documented in Arctic explorers consuming polar bear livers, which are rich in vitamin A. Clinically, it presents as large areas of desquamation associated with headache and vomiting. Chronic toxicity is more common and displays features associated with side effects of retinoid therapy: alopecia, exfoliation, and skin dryness. Pseudotumor cerebri with papilledema may occur early before any other signs. All symptoms and signs resolve in days to weeks following cessation of supplementation.

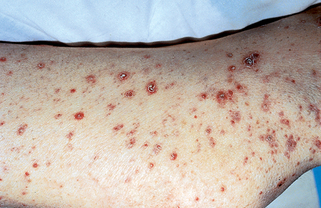

18. What is acrodermatitis enteropathica?

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is a rare autosomal recessive disorder of intestinal zinc absorption. Zinc is normally incorporated into multiple types of enzymes present in all body tissues but is concentrated five- to sixfold in the epidermis. Deficiency of this trace element results in dramatic findings. The classic triad consists of acral dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea. Growth failure, anemia, impaired wound healing, and mental and emotional disturbances are also seen. The periorificial and acral dermatitis (Fig. 40-4) was considered to be pathognomonic in the past, but more recent reports have described similar cutaneous eruptions in essential fatty acid deficiency, biotin deficiency, and infants treated for organic acidurias. Acrodermatitis enteropathica develops in days to weeks after birth in bottle-fed infants and shortly after weaning in breastfed infants. Uncommonly, signs and symptoms are first noted at puberty.

19. Has the gene responsible for inherited acrodermatitis enteropathica been identified?

20. How is acrodermatitis enteropathica diagnosed and treated?

Diagnosis is made by demonstrating low plasma or serum zinc levels. Hair zinc levels reflect only long-term status and may not reflect early deficiency. Oral or intravenous zinc supplementation promotes rapid improvement, with reversal of most clinical manifestations in hours to days. Untreated infants develop failure to thrive, with progressive deterioration and death.

21. Can zinc deficiency be acquired?

Yes, in association with diabetes mellitus, collagen vascular disease, pregnancy, Crohn’s disease, nephrotic syndrome, dialysis, renal tubular disease, burns, antimetabolite drugs, alcoholism, malabsorption syndromes, and HIV infection. Clinical findings are similar to those of the inherited form of acrodermatitis enteropathica.

22. What is carotenoderma?

Carotenoderma is a yellow or orange skin discoloration most prominent on the palms, soles, and central face. It is more common in children and is associated with ingestion of carotene found in carrots, oranges, squash, spinach, yellow corn, butter, eggs, pumpkin, yellow turnips, sweet potatoes, and dried seaweeds. It is clinically apparent when serum carotene levels are three to four times normal. The discoloration spares the sclera and mucosal surfaces, which can be used to differentiate this benign condition from jaundice (Fig. 40-5). Elimination of the offending food results in normalization of skin color in 2 to 6 weeks. Carotenemia also occurs in diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism due to impaired hepatic conversion of carotene to vitamin A. It has been reported in anorexia nervosa with undetermined etiology.

23. Has supplementation with micronutrients or homeopathic remedies been associated with any cutaneous disorders?

Yes. Ginkgo, garlic and ginseng inhibit platelet activation and aggregation and may increase intraoperative bleeding and cause postoperative hematoma and ecchymosis. It is recommended to stop these supplements one week before surgery. Certain Chinese herbal supplements and proprietary medicines have been reported to contain inorganic arsenic. This has caused chronic arsenicism, clinically manifested as Bowen’s disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ) and arsenical keratoses on the palms and soles.