Chapter 36 Cutaneous manifestations of endocrinologic disease

1. How does endocrinologic disease cause skin disorders?

There are several mechanisms by which endocrinologic diseases produce cutaneous changes:

• Hormones interact with cell surface receptors to regulate cellular function. Many cell types in the skin have hormonal receptors. Deficient or excess hormone levels can alter skin metabolism. An example is the warm and moist skin associated with hyperthyroidism due to the thyroid-stimulating hormone (thyrotropin, TSH) receptors in the skin.

2. What is necrobiosis lipoidica?

This disease is characterized by granulomatous inflammation and fibrosis with a marked predilection to occur on the pretibial areas, although it may occur at other sites. Early lesions present as nondiagnostic erythematous papules and evolve into annular lesions that have a yellowish-brown color, dilated blood vessels, and central epidermal atrophy (Fig. 36-1). Fully developed pretibial lesions can be diagnosed by clinical appearance.

3. Do all patients with necrobiosis lipoidica have diabetes?

No. In a study of 171 patients with necrobiosis lipoidica, about 60% had diabetes. Many other patients subsequently developed diabetes, had abnormal glucose tolerance tests, or had a strong family history of diabetes. Only about 10% of patients were not in a high-risk group to develop diabetes. In a more recent study with 65 patients, 22% either had or developed diabetes. Patients with necrobiosis lipoidica should be screened for diabetes.

Peyrí J, Moreno A, Marcoval J: Necrobiosis lipoidica, Semin Cutan Med Surg 26:87–89, 2007.

4. Is necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum common in patients with diabetes?

5. Does glucose control affect necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum?

6. What other skin findings are associated with insulin resistance?

Acanthosis nigricans. Insulin-like growth factors are produced by the liver in response to high levels of circulating insulin. These growth factors bind to epidermal growth factor receptors or other receptors and produce thickening of the epidermis and hyperkeratosis. Acanthosis nigricans can be found in 30% to 50% of patients with diabetes and correlates with obesity and insulin resistance. Acanthosis nigricans may predict the future development of diabetes in high-risk populations with strong family histories for diabetes and obesity.

Hermanns-Le T, Scheen A, Pierard GE: Acanthosis nigricans associated with insulin resistance: pathophysiology and management, Am J Clin Dermatol 5:199–203, 2004.

7. What does acanthosis nigricans look like?

Acanthosis nigricans presents as velvety, hyperpigmented plaques, most commonly in neck creases and axillae (Fig. 36-2). The patient may complain about “dirty skin” under the arms that is impossible to clean. The tops of knuckles may also demonstrate small papules.

8. Is diabetes the only condition associated with acanthosis nigricans?

No. There are many causes of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. Endocrine diseases, such as Cushing’s syndrome with excess cortisol, acromegaly with excess growth hormone, or polycystic ovarian disease, and medications that promote hyperinsulinemia are also associated with acanthosis nigricans. Certain malignancies, most commonly gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas, may autonomously make insulin-like growth factors and thus produce acanthosis nigricans. Oral acanthosis nigricans suggests malignancy as the cause.

9. What bacterial infections are more common in diabetic patients?

Cutaneous bacterial infections are relatively more common and severe in patients with diabetes. Diabetic foot ulcers are a leading cause of morbidity and health care cost. Foot numbness from diabetic neuropathy prevents recognition of injury and hyperglycemia impairs white blood cell function, allowing bacterial infection. Staphylococcal folliculitis or skin abscesses are well described in diabetic patients and respond well to antibiotics and surgical drainage of abscesses. Diabetic patients may develop external necrotizing ear infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

10. What are the most common fungal skin infections associated with diabetes?

Candidiasis, usually caused by Candida albicans. Mucocutaneous candidiasis is characterized by red plaques with adherent white exudate and satellite pustules. Candidal vulvovaginitis is extremely common. Perianal dermatitis in either men or women may be caused by Candida. Other mucocutaneous forms of candidiasis include thrush (infection of oral mucosa), perlèche (angular cheilitis), intertrigo (infection of skinfolds), erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica chronica (finger webspace infection), paronychia (infection of the soft tissue around the nail plate), and onychomycosis (infection of the nail). The mechanism appears to involve increased levels of glucose that serve as a substrate for Candida species to proliferate. Patients with recurrent cutaneous candidiasis of any form should be screened for diabetes.

13. What other skin disorders are commonly encountered in diabetic patients?

Diabetic dermopathy (atrophic, scarred, hyperpigmented papules on the anterior leg), periungual telangectasias, yellow skin and nails, skin tags, and diabetic thick skin occur commonly. Bullous disease of diabetes (tense bullae of the lower extremities), vitiligo, and scleroderma-like symptoms such as diabetic stiff hands and thickened skin on the upper back (scleredema adultorum) are less common associations.

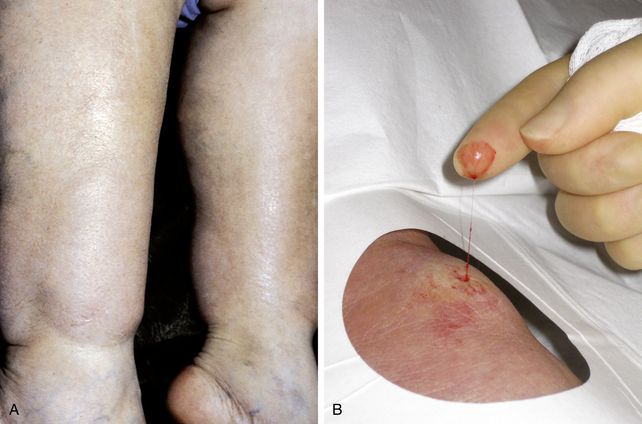

14. Describe the clinical manifestation of pretibial myxedema.

Pretibial myxedema is characterized by brawny, indurated plaques over the pretibial areas. These plaques may be skin-colored or have an unusual brownish-red color (Fig. 36-3A). On biopsy, the skin is infiltrated by mucinous ground substance (Fig. 36-3B). Pretibial myxedema is specific for Graves’ disease, a frequent cause of hyperthyroidism, but occurs in only 3% to 5% of patients with the disease. Pretibial myxedema is often associated with Graves’ ophthalmopathy (bulging eyes or exophthalmos) and acropachy (clubbed nails). Treatment of hyperthyroidism has no effect on pretibial myxedema.

15. Why does treatment of Graves’ disease have no effect on pretibial myxedema?

Graves’ hyperthyroidism is an autoimmune disease produced by autoantibodies that bind to thyrotropin (TSH) receptors in the thyroid gland, stimulating the thyroid to produce and release thyroid hormone. Pretibial connective tissue also has thyrotropin receptors. Stimulation of these receptors is the proposed mechanism of mucin production in pretibial connective tissue. Treatment of Graves’ disease treats hyperthyroidism but not the underlying autoimmune disease.

16. What are the skin manifestations of hypothyroidism?

• Mild hypothyroidism: The skin is dry, scaly, cold, and pale. Dryness and scale may make the skin pruritic. The nails are brittle.

• Severe and long-standing hypothyroidism: There may be yellow and diffusely thickened skin (Fig. 36-4), loss of the outer third of the eyebrows and enlarged and thickened lips and tongue.

21. What are the skin manifestations of hyperthyroidism?

They are the opposite of hypothyroidism. Hyperthyroid skin is moist, warm, smooth, and erythematous. The nails may separate from the nailbed (onycholysis). The skin may be pruritic. Because itchy skin may occur with either high or low thyroid hormone, patients with itchy skin of unknown cause should have thyroid disease excluded.

22. Which hormone gives the skin a darkened or tanned appearance?

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) darkens the skin by stimulating melanocytes to produce melanin. In contrast to normal tanning, the darkening is often accentuated in palmar creases and mucous membranes. (A note of caution: dark skin creases and mucous membranes may be a normal variant in more darkly pigmented races.) The most common cause of elevated ACTH levels is Addison’s disease, in which hypofunctioning adrenals and deficient serum cortisol remove the negative feedback inhibition of the pituitary gland that increases ACTH production.

23. What skin disease is associated with insulin-dependent diabetes, hypothyroidism, and Addison’s disease?

Vitiligo. This is a trick question. Vitiligo is not caused by deficient hormones but is an autoimmune disease that results in the destruction of melanocytes and is associated with the autoimmune endocrinopathies. Vitiligo presents clinically as white macules, most commonly on the face and hands. Vitiligo is present in 4% of patients with insulin-dependent diabetes, 7% of patients with Graves’ disease, and 15% of patients with Addison’s disease. There is also a familial predisposition to this group of diseases.

24. What skin findings are associated with glucocorticoid excess or Cushing’s disease?

The skin is generally thin and atrophic. Wound repair is inhibited, and striae developed in sites such as the abdomen, upper chest, and buttocks, where the skin is normally stretched. These striae are often large and purple in color, in contrast to idiopathic or pregnancy-induced striae (Fig. 36-5). The skin has a ruddy appearance, and telangiectasias may be prominent. The skin bruises and tears easily. Other skin changes include hypertrichosis, dryness, fragility of the skin, and facial acne. These changes may also be seen in skin that has been treated with high-strength topical steroids for long periods of time. Broadened facial features (moon facies), increased subcutaneous fat on the upper back and neck (buffalo hump), and truncal obesity are also characteristic.

26. Which hormones have the greatest effect on sebaceous glands and hair?

The androgens. Androgens at the time of puberty induce sebaceous gland activity and the development of acne. Excess androgen in women may cause acne, hirsutism (increased facial hair), and/or alopecia. Associated signs may include hyperpigmentation of genital and areolar skin and clitoromegaly. Possible causes of hirsutism and acne in women include adrenal and ovarian tumors, prolactin-producing pituitary tumors, polycystic ovarian disease, adrenal enzyme deficiencies, and familial acne and hirsutism that may be related to increased end-organ sensitivity to normal circulating levels of androgens. Most acne and hirsutism in women is benign and familial. Screening tests for tumors include serum prolactin; dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), which is an androgen produced by the adrenal glands; and free testosterone.

27. Are there medications and nutritional supplements that may cause acne?

Yes. Supplements and medications that have androgen effects and can cause acne may not appear in the patient’s list of medications. New-onset acne in a recreational weightlifter, either male or female, may result from the abuse of androgens. New-onset acne in a young woman may be from birth control pills that are low in estrogen. The progesterone-like hormone in many birth control pills and in all long-acting depository forms may have androgen effects. New onset acne in a perimenopausal woman may result from small amounts of testosterone added to some estrogen supplements. High-dose glucocorticoid therapy can also cause acne. The acne that occurs from changing hormone levels takes 4 to 6 weeks to appear.

28. What hormonal methods are available to treat acne?

Estrogens often antagonize the effects of androgens. High-dose estrogen birth control pills that use progesterone-like hormones with few androgen effects have been approved for the treatment of acne in women. Spironolactone, an aldosterone antagonist that acts as a relatively weak antiandrogen, has been used to treat hormone related acne in women over the age of 35. Additionally, it has been used for treatment of hirsuitism, androgenic alopecia, and hydradenitis suppurativa due to its antiandrogen effects.

Shaw J: Antiandrogen and hormonal treatment of acne, Dermatol Clin 14:803–811, 1996.

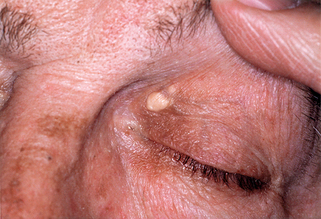

29. What are xanthelasma?

Xanthelasma (palpebra) are distinctive yellowish plaques on the eyelids and around the eyes caused by cholesterol deposition within the skin (Fig. 36-6). Although people with xanthelasma may have normal total cholesterol and triglyceride levels, they often have more subtle lipid abnormalities associated with high cardiovascular risk and deposition of cholesterol within blood vessels. As opposed to other xanthomas, treatment of xanthelasma with surgical excision is often successful.

30. What are eruptive xanthomas?

Eruptive xanthomas are multiple, small, skin-colored to yellow-brown papules that occur in crops, most commonly on the buttocks, thighs, or elbows (Fig. 36-7A). On biopsy, there is accumulation of triglyceride within histiocytes and around blood vessels in the skin. These distinctive papules are a cutaneous sign of very high triglyceride levels. These patients are at risk to develop pancreatitis, which may be severe. Often, eruptive xanthomas are precipitated by the new onset of diabetes.

31. How do eruptive xanthomas differ from tuberous xanthomas?

Tuberous xanthomas are larger and deeper than eruptive xanthomas and may be palpated as nodules similar to a large radish, a small turnip, or other vegetable tuber or root within the deep dermis or subcutaneous fat (Fig. 36-7B). These xanthoms are the result of cholesterol accumulation within these tissues, in contrast to the smaller, papular, eruptive xanthomas that contain triglyceride. Tuberous xanthomas are a marker of high cholesterol levels, and these patients are at risk for coronary artery disease at a young age. Tendinous xanthomas (e.g., similar lesions attached to large tendons, such as the Achilles tendon) may also be present.

32. What are the cutaneous features of acromegaly?

Acromegaly is the result of excess pituitary growth hormone present after puberty. Bone thickening is prominent and results in coarse facies and enlarged hands. The skin changes are the result of the production of insulin-like growth factors and, thus, overlap with changes due to insulin resistance. The skin is hypertrophied and thickened, and acanthosis nigricans may be present. These changes may be accentuated on the scalp as whorled furrowing (cutis vertices gyrata) in 30% of patients.

Centurión SA, Schwartz RA: Cutaneous signs of acromegaly, Int J Dermatol 41:631–634, 2002.

33. How does panhypopituitarism affect the skin?

The skin in patients with panhypopituitarism appears pale, and there are fine wrinkles around the eyes and mouth. Body hair and genital hair are sparse. Sweat and sebum production are also diminished. The skin dryness and thickening are not as prominent as in primary hypothyroidism because there is some autonomous thyroid gland function in panhypopituitarism.

34. How do you diagnose endocrine disease from skin findings?

• Most skin findings are nonspecific but related to the specific effect of the hormone on the skin. An example is dry, thickened skin in hypothyroidism or skin infections in diabetes. Dry skin and skin infections may occur in many other diseases or, in most cases, such as dry skin in a dry climate or folliculitis, happen in otherwise normal people.

• Nonspecific skin findings are grouped with nonspecific findings from other organ systems to suggest the appropriate endocrine diagnosis. Dry, thickened skin with weight gain, fatigue, depression, and lethargy would be highly suggestive of hypothyroidism. Multiple skin or mucous membrane infections with yeast or bacteria coupled with increased urination should prompt tests for diabetes.

• More specific skin findings often occur in a minority of patients with endocrinologic disease but are highly suggestive of the diagnosis when present. Patients with acanthosis nigricans or necrobiosis lipoidica should be screened for diabetes. Pretibial myxedema is a feature of Graves’ hyperthyroidism. Xanthelasma is associated with cardiovascular risk and more subtle lipid abnormalities. Eruptive xanthomas occur with marked hypertriglyceridemia and tuberous xanthomas with very high serum cholesterol.