Chapter 39 Cutaneous manifestations of AIDS*

| Neoplastic Diseases | Infectious Diseases |

|---|---|

| Kaposi’s sarcoma Lymphoma Squamous cell carcinoma Basal cell carcinoma |

Bacterial Staphylococcus aureus infections Syphilis Bacillary angiomatosis Fungal Candida, Penicillium marneffei Dermatophytosis Cryptococcosis Histoplasmosis Viral Human papillomavirus (HPV) Molluscum contagiosum Herpes simplex virus (HSV) Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Epstein-Barr virus Arthropods Scabies |

| PAPULOSQUAMOUS DISEASES | |

| Seborrheic dermatitis Xerosis/acquired ichthyosis Psoriasis Reiter’s syndrome |

|

| MISCELLANEOUS DISEASES | |

| Eosinophilic folliculitis Drug eruptions Hyperpigmentations Photoeruptions Pruritus Lipodystrophy Granuloma annulare Aphthosis |

Dover JS, Johnson RA: Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection: parts 1 and 2, Arch Dermatol 127:1383–1391, 1549–1558, 1991.

James W, editor: AIDS: a ten-year perspective, Dermatol Clin 9:391–615, 1991.

* Costner M, Cockerell CJ: The changing spectrum of the cutaneous manifestations of HIV disease, Arch Dermatol 134:1290–1292, 1998.

Ahuja D, Albrecht H: HIV and community-acquired MRSA, AIDS Clin Care 21:21–23, 2009.

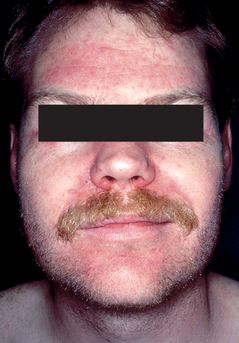

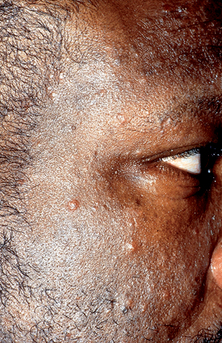

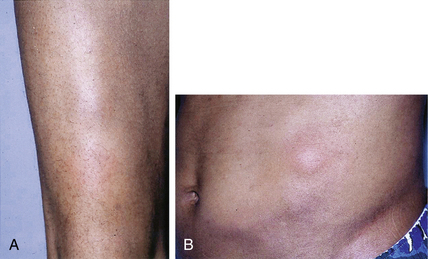

Disfigurement and pain secondary to edema can occur, especially on the face, genitals, and lower extremities. Koebnerization, or formation of new lesions at sites of trauma, can be seen. Secondary bacterial infection can also occur. Lesions can be arranged in several known patterns, such as a follicular (clustered) pattern (Fig. 39-2), pityriasis rosea–like pattern, or dermatomal pattern.

Resnick L, Herbst JS, Raab-Traub N: Oral hairy leukoplakia, J Am Acad Dermatol 22:1278–1282, 1990.

Simpson-Dent SL, Fearfield LA, Staughton RCD: HIV-associated eosinophilic folliculitis: differential diagnosis and management, Sex Transm Infect 75:291–293, 1999.

Key Points: Cutaneous Manifestations of HIV-infection