Chapter 66 Current techniques of adenoidectomy

1 INTRODUCTION

The clinical significance of adenoid hypertrophy was not truly appreciated until the mid-19th century. This was due to their relatively inaccessible location given the technology available at that time. Once discovered, various techniques for the removal of the adenoids were developed. Some of these basic techniques have remained with us since that time.

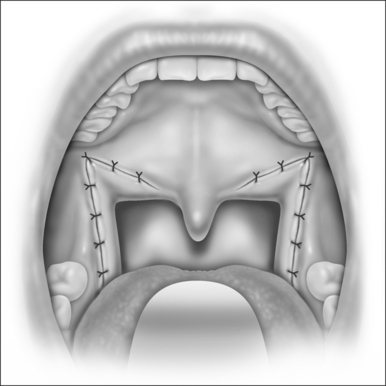

3.1 CURETTE ADENOIDECTOMY

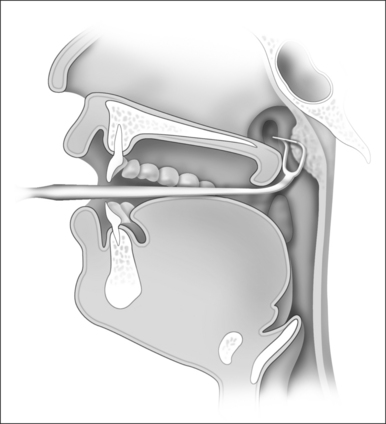

The use of a curette to remove the adenoids dates back to some of the earliest attempts at this procedure and remains an incredibly popular technique worldwide. The original design of Jacob Gottenstein has been modified and many different lengths, widths and curvatures are available. The basic principle is that of a sharp horizontal knife-edge that is designed to cut through the base of the adenoid bed. The instrument is designed to follow the natural curvature of the nasopharyngeal skull base (Fig. 66.1).

3.2 ABLATION ADENOIDECTOMY

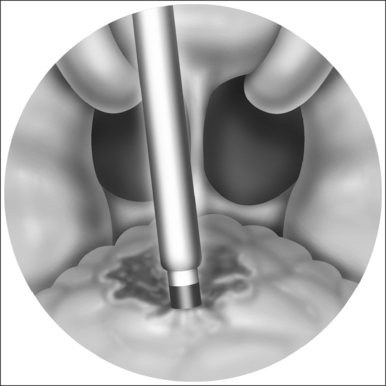

The widespread use of the suction monopolar cautery unit to achieve hemostasis after adenoidectomy naturally led to its use as a primary means of reducing adenoid tissue. With the patient in the Rose position, as described above, the adenoid pad is viewed with a mirror. The monopolar cautery unit, generally set at 30–40 watts, can then be shaped to fit the patient’s unique anatomy. Starting at the choana and working inferiorly, the adenoids are sequentially ablated using the cautery unit (Fig. 66.2). As the tissue fluid is vaporized there is dramatic reduction in the size of the adenoid tissue. Care is taken to avoid inadvertent cautery of non-adenoidal tissue. Bleeding tends to be minimal using this technique and can be controlled with any of the methods described above.

3.3 TRANSNASAL ADENOIDECTOMY

Essentially, two types of transnasal procedures exist. Both utilize rigid nasal endoscopes as in endoscopic sinus surgery. In traditional transnasal techniques the adenoids are removed using sinus instruments such as Blakesley forceps. More recently the soft tissue shaver has been advocated to allow more rapid removal of the adenoid tissue.

3.4 POWERED TRANSORAL ADENOIDECTOMY

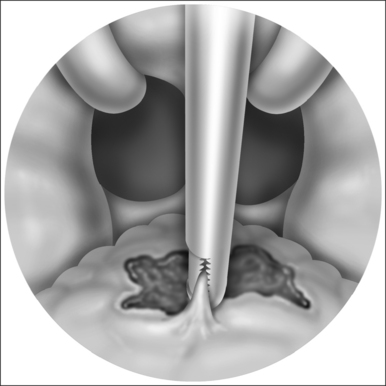

With the patient in the Rose position with transnasal catheters and a mouth gag in place, the mirror is used to visualize the nasopharynx. Various pre-curved blades exist on the market and these allow for continued visualization during removal (Fig. 66.3). Starting in the region of the choana, the adenoid tissue is removed in a side-to-side manner that progresses inferiorly. The microdebrider is generally set on oscillating mode at 1500 rpm and tissue is removed only at the location of the blade, which is kept under vision at all times. This allows for precise control during removal of tissue. By angling the blade, the Eustachian tube orifice can be cleared of any adenoid tissue without injury. Furthermore, the depth of dissection can be more effectively monitored compared to the curette technique to avoid inadvertent injury to the underlying musculature. This technique also allows the surgeon to very precisely leave adenoid tissue inferiorly to minimize the risk of postoperative velopharyngeal insufficiency, especially in the child with a developmental anomaly of the palate.

Once the adenoids are removed bleeding is controlled as described above.

3.6 POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT AND COMPLICATIONS

Upon arrival in the recovery room, patients should be adequately monitored with continuous pulse oximetry. Once the child is fully awake, oral diet may be resumed. Initially this is in the form of clear liquids and diet may then be advanced to soft foods. Adenoidectomy performed without concurrent tonsillectomy generally has a quicker recovery time with much less postoperative pain. The use of narcotics is generally not necessary and should probably be avoided in the child with sleep apnea. Following adenoidectomy, we favor the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen, alternating every 3 hours with acetaminophen. The best literature available suggests that this regimen is more effective for control of pain, and does not pose an increased risk of bleeding.

1. Clemens J, McMurry JS, Willging JP. Electrocautery versus curette adenoidectomy: comparison of postoperative results. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1998;43:115-122.

2. Elluru RG, Johnson L, Myer CM. Electrocautery adenoidectomy compared with curettage and power-assisted methods. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:23-25.

3. Emerick KS, Cunningham MJ. Tubal tonsil hypertrophy: a cause of recurrent symptoms after adenoidectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:153-156.

4. Giannoni C, Sulek M, Friedman EM, et al. Acquired nasopharyngeal stenosis: a warning and review. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:163-167.

5. Heras H, Koltai PJ. Safety of powered instrumentation for adenoidectomy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1998;44:149-153.

6. Koltai PJ, Kalathia AS, Stanislaw P. Power assisted adenoidectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:685-688.

7. Stewart MG, Glaze DG, Friedman EM. Quality of life and sleep study findings after adenotonsillectomy in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Otolarynger Head Neck Surg. 2005;131(4):308-314.

8. Yanagisawa E, Ho SY, Mirante JP. Powered transnasal adenoidectomy. In: Yanagisawa E, Christmas DA, Mirante JP, editors. Powered Instrumentation in Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. Canada: Thomson Learning; 2001:247.