Chapter 59 Current techniques for the treatment of velopharyngeal insufficiency

1 INTRODUCTION

Velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI) is a significant speech disorder. This is usually identified and addressed in childhood, but may be seen as a consequence of central nervous system disease or injury, peripheral nerve injury or palate resection with cancer ablation in the adult. VPIcan be a result of inappropriate articulation and hence, in these cases, remediable by aggressive speech therapy. All too often the treatment will need to be surgical. In this chapter, the surgical treatment will be addressed. Prosthetic management can be quite useful as well and will be addressed in the patient selection section, but will not be fully described here.

2 PATIENT SELECTION

If the decision is made that surgery is necessary, endoscopic evaluation of the velopharynx during speech is needed to decide the type and extent of surgery needed.

3 COMMON CONSIDERATIONS FOR THESEPROCEDURES

The surgery is performed under general anesthesia. Usually the use of an oral RAE tube will allow less interference with the field. The Dingmann mouth gag is usually used. It has the advantage of self-retaining lateral retractors and springs to allow suture retention. Other mouth gags used in tonsil surgery can be employed as well. Craig Senders suggested that releasing the pressure on the tongue during the surgery allowed improved blood flow and likely decreased pain.1

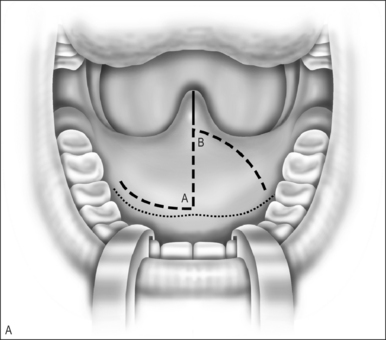

4 FURLOW DOUBLE OPPOSING Z-PLASTY

A Z-plasty lengthens a scar. In VPI the problem often includes a short palate. The double Z-plasty lengthens the palate. The initial ‘Z’ can be made in either direction but the right-handed surgeon seems to do better as pictured (Fig. 59.1A). The posteriorly based flaps are always the myomucosal flaps. The anteriorly based flaps are mucosa only. Kathy Sie suggests rounding the tips of the flaps to improve the vascular supply.2 The incision is carried through the oral cavity mucosa. As the incision is madein the left hemipalate, care must be taken to maintain a small amount of mucosa behind the posterior edge of the hard palate so that suturing is easier. Careful dissection through the levator and tensor veli palatini tendon brings one to the nasal mucosal layer. The plane is usually well defined. Meticulous blunt and sharp dissection separates the undersurface of the muscle bundle from the nasal mucosa.

The anteriorly based mucosal flap is raised off the palatal muscles. This mucosa is markedly thicker than the nasal mucosa, but is still prone to injury if the dissection is not careful. The midline incision can be made through the palate at the initial step of the operation, or once both oral flaps are raised (Fig. 59.1B).

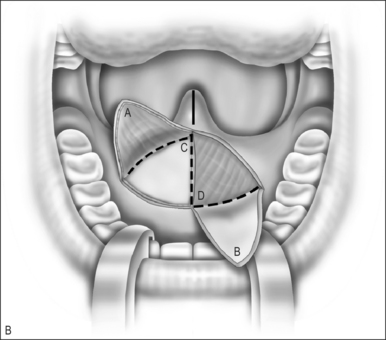

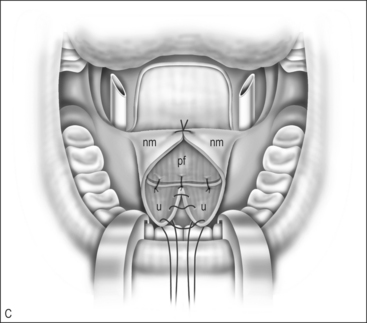

The nasal layer is closed by rotation of the left nasal mucosal flap across the midline, suturing it to the area of the right posterior hard palate. The nasal layer myomucosal flap is rotated to the left to be sutured to the defect. This places the midline incision at the posterior left hemipalate and the anterior incision along the nasal mucosal flap (Fig. 59.1C).

The oral mucosal flap is now rotated to the left and the myomucosal flap rotated to the right and closed. One can see the muscle bundles are now in a horizontal orientation and posterior in the palate. The mucosal layers are more anterior against the hard palate. The uvula is reapproximated (Fig. 59.1D).

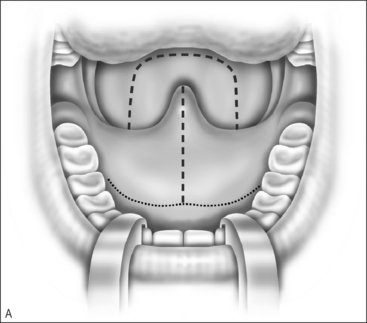

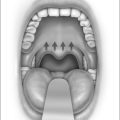

5 PHARYNGEAL FLAP

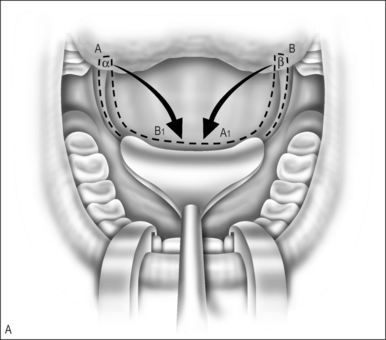

The surgery is done with a midline split of the soft palate (Fig. 59.2A). The posteriorly based nasal mucosal flap is elevated from the palate with careful blunt and sharp dissection. The nasal mucosa is divided just at the hard–soft palate border. The midline pharyngeal flap is developed from the center of the pharynx. Its width would be determined by the degree of obturation needed, as based on the preoperative endoscopy. This is elevated to the level of the hard palate.

In order to reduce the possibility of lateral port scarring that will increase the risk of postoperative airway obstruction, either an endotracheal tube or other catheter is placed through each nare and brought into the nasopharynx. The catheter size is determined by the desired port size.

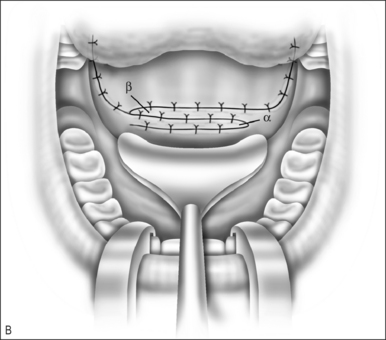

The pharyngeal flap is sutured to the posterior aspect of the hard palate (Fig. 59.2B). The nasal mucosal flaps are then sutured to the pharyngeal flap to cover the raw surface area. The soft palate is then closed in layers, reapproximating the muscle, the oral cavity mucosa and the uvula (Fig. 59.2C).

The defect in the posterior wall may be loosely approximated.

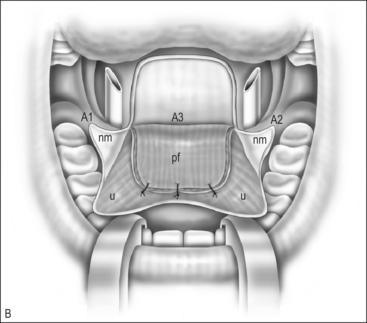

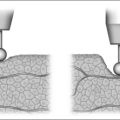

6 SPHINCTER PHARYNGOPLASTY

Superiorly based myomucosal lateral pharyngeal wall flaps are elevated (Fig. 59.3A). The flap can include the posterior tonsillar pillar, or only the lateral pharyngeal wall. If the posterior pillar is used the flap tends to be more obstructive but is very useful in a large gap. The flap design is based on the amount of obturation needed. If little obturation is needed, the flap can be longer and narrower. If the sphincter needs to be tight, the shorter, wider flap creates a much smaller port.

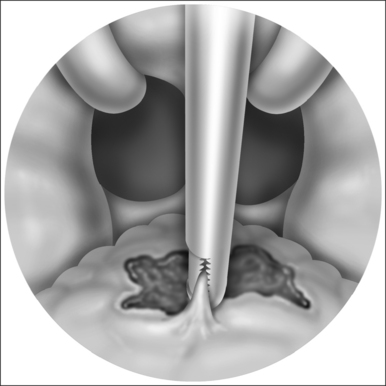

A horizontal incision is made at the point of insertion (Fig. 59.3A). This can be defined by the point of maximal palatal elevation as seen in a lateral x-ray taken during speech, landmarks seen at the time of endoscopy or, as in many cases, placed as high as possible in the nasopharynx. Often this can be problematic if there is adenoid tissue in the way. Suturing in the adenoids is difficult and increases the risk of bleeding and the flap not holding. De Serres presented a technique to help with this problem.3 A microdebrider is used to remove the adenoids from the area of the horizontal incision. Hemostasis is assured and the flaps can be sutured into this space.

There are many ways to suture the flaps. The most practical way is to bring the left flap into the nasopharynx, suturing the posterior cut edge to the superior portion of the horizontal incision. The right myomucosal flap must be rotated at its base 180° on axis and then into the nasopharynx so the anterior cut edge is sutured to the inferior aspect of the horizontal incision (Fig. 59.3B). This opposes the raw surfaces (Fig. 59.3C). The degree of overlap and the length and width of the flap determine size of the central port. Exposure of the nasopharynx can be difficult. Retraction of the palate can be done with a uvula retractor as seen in the illustrations or bilateral transnasal red rubber catheters. Adequate visualization for accurate suture placement is a must.

The free edges of the flaps are sutured together (Fig. 59.3C). The defect created as the flaps were raised can be loosely approximated as well.

7 POSTERIOR WALL AUGMENTATION

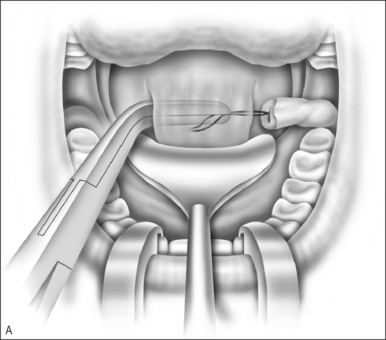

A right-angle clamp is placed through the pocket and the long suture is grasped. The Alloderm roll is pulled into the pocket (Fig. 59.4&). Firmly holding the graft in position, multiple absorbable sutures are placed through the graft to stabilize it in the nasopharynx during the healing process. The long suture is cut and the vertical incisions closed.

8 POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT ANDCOMPLICATIONS

The use of anti-emetics during and after the operation will hopefully improve the immediate postoperative course. Antibiotics during and after the procedure may be helpful in preventing infection and improving healing.

10 CONCLUSION

The treatment of VPI should be based on an understanding of the closure pattern during speech. A major potential risk of the surgery is airway obstruction, often demonstrated as obstructive sleep apnea. Of the procedures discussed, those with the least risk for airway obstruction are the Furlow and posterior wall augmentation. If there is postoperative sleep apnea the pharyngeal flap and sphincter can be revised to open the port and improve breathing, or CPAP or BiPAP can be used.

1. Senders CW, Eisele JH. Lingual pressures induced by mouthgags. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1995;33(1):53-60.

2. Sie KC, Gruss JS. Results with Furlow palatoplasty in the management of velopharyngeal insufficiency. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(7):2588-2589. author reply p. 2590

3. de Serres LM, Deleyiannis FW, Eblen LE. Results with sphincter pharyngoplasty and pharyngeal flap. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1999;48(1):17. 25 AU: Please could you check volume number; is it 25 or 58? Neither of these seem to fit with ref from same publication below in Further reading.

1. Antony AK, Sloan GM. Airway obstruction following palatoplasty: analysis of 247 consecutive operations. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2002;39(2):145-148.

2. Armour A, Fischback S, Klaiman P, Fisher DM. Does velopharyngeal closure pattern affect the success of pharyngeal flap pharyngoplasty? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(1):45-52.

3. D’Antonio LL, Eichenberg BJ, Zimmerman GJ. Radiographic and aerodynamic measures of velopharyngeal anatomy and function following Furlow Z-plasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106(3):539-549. discussion pp. 550–3.

4. Furlow LTJr. Cleft palate repair by double opposing Z-plasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78(6):724-738.

5. Larossa D, Jackson OH, Kirschner RE. The children’s hospital of Philadelphia modification of the Furlow double-opposing Z-palatoplasty: long-term speech and growth results. Clin Plast Surg. 2004;31(2):243-249.

6. Liao YF, Noordhoff MS, Huang CS. Comparison of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children with cleft palate following Furlow palatoplasty or pharyngeal flap for velopharyngeal insufficiency. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2004;41(2):152-156.

7. Mann EA, Sidman JD. Results of cleft palate repair with the double-reverse Z-plasty performed by residents. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111(1):76-80.

8. March JL. Management of velopharyngeal dysfunction: differential diagnosis for differential management. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14(5):621-628.

9. Mehendale FV, Sommerlad BC. Surgical significance of abnormal internal carotid arteries in velocardiofacial syndrome in 43 consecutive Hynes pharyngoplasties. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2004;41(4):368-374.

10. Peat BG, Albery EH, Jones K, Pigott RW. Tailoring velopharyngeal surgery: the influence of etiology and type of operation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93(5):948-953.

11. Perkins JA, Lewis CW, Gruss JS, et al. Furlow palatoplasty for management of velopharyngeal insufficiency: a prospective study of 148 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(1):72-80. discussion pp. 81–4.

12. Saint Raymond C, Bettega G, Deschaux C. Sphincter pharyngoplasty as a treatment of velopharyngeal incompetence in young people: a prospective evaluation of effects on sleep structure and sleep respiratory disturbances. Chest. 2004;125(3):864-871.

13. Senders CW, Sykes JM. Modifications of the Furlow palatoplasty (six- and seven-flap palatoplasties). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121(10):1101-1104.

15. Witt PD, Marsh JL, Marty-Grames L, Muntz HR. Revision of the failed sphincter pharyngoplasty: an outcome assessment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96(2):129-138.

14. Witt PD, Marsh JL, Muntz HR. Acute obstructive sleep apnea as a complication of sphincter pharyngoplasty. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1996;33(3):183-189.

16. Witt PD, O’Daniel TG, Marsh JL. Surgical management of velopharyngeal dysfunction: outcome analysis of autogenous posterior pharyngeal wall augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99(5):1287-1296.

17. Ysunza A, Garcia-Velasco M, Garcia-Garcia M. Obstructive sleep apnea secondary to surgery for velopharyngeal insufficiency. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1993;30(4):387-390.

18. Ysunza A, Pamplona C, Ramirez E. Velopharyngeal surgery: a prospective randomized study of pharyngeal flaps and sphincter pharyngoplasties. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(6):1401-1407.